PROLOGUE

Thank God the war was over.

Moses Carver came to Southwest Missouri in 1843. The Preemption Act of 1841 allowed him to buy 240 acres of the choicest land in Newton County, with timber, prairie, two springs and a creek nearby, for only $1.25 an acre. By the time the war started, Moses and his wife, Susan, had improved the property until it was one of the most valuable in the area. Like most Missourians, he did not raise only cash crops for sale. Rather, Carver grew wheat, oats, potatoes, hay and flax. Carver had a reputation as an eccentric and aloof neighbor. He cultivated bees and bred racehorses. The locals said he even had a special way with the animals—roosters sat on his shoulders and squirrels ate from his hand. He was also known as a “good fiddler.”

The Carvers had no children. As they grew older, they needed help to run the farm. Although he had a white hired hand, Carver bought a slave woman named Mary from a neighbor. Carver was neither a fire-eating slaveholder nor a dedicated abolitionist. He disapproved of slavery, but it was difficult to find white men who would stay on a farm for any length of time, and certainly there were few, if any, white women who would hire out as domestics.

Mary gave birth to two boys. Their father was likely a man living on a neighboring farm. The older boy, Jim, was born in October 1859. The younger boy, George, was born in late 1864 or the spring of 1865—as with many slaves, the exact date was not recorded.

Although a slave owner, Carver was a Unionist. That was not easy living in Newton County. Carver’s corner of Missouri lay on the path of Confederate and Union armies as they fought for control of the state. Pro-Southern governor Claiborne Jackson and a rump legislature that escaped from Jefferson City in 1861 met just a few miles away in Neosho to approve secession and entry into the Confederate States of America. Carver likely could hear the guns when the armies clashed at Newtonia, only about ten miles away.

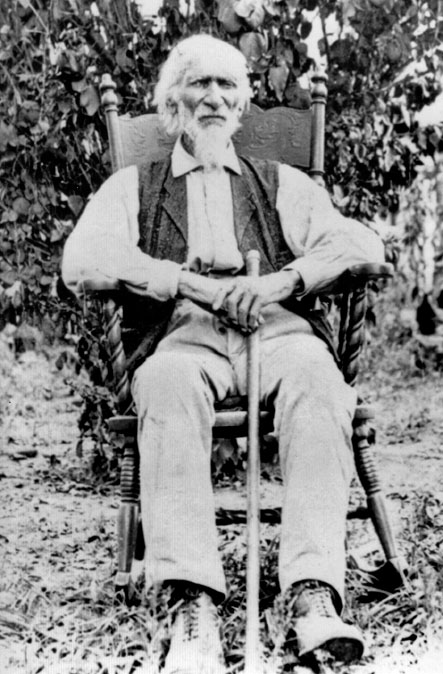

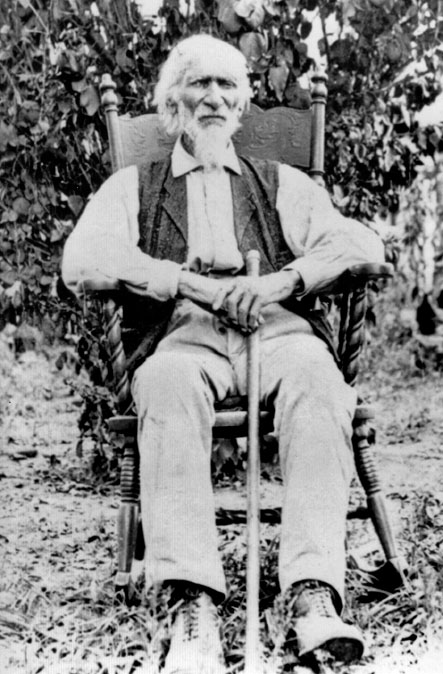

Moses Carver. George Washington Carver National Monument.

Worse yet, Newton County also was in the heart of the guerrilla war. John Coffee and Tom Livingston, among other bushwhackers, raided back and forth across the area, chased by Federal troops. Neither side showed much patience with civilians.

Carver tried to stay out of the way of marauding or “foraging” Confederate and Union forces. He was too old to join the militia. For the most part, he succeeded in keeping a low profile. But he was not entirely successful and nearly paid for it with is life.

In late 1862, a band of guerrillas (likely on their way to winter quarters in Texas) appeared at the Carver farm. They did not want any of his livestock or food—they wanted Carver’s money. Moses refused to turn it over. The guerrillas then put a rope around Moses’s neck, hung him from a tree in the yard and even put hot coals to his feet. Moses still refused. Frustrated, the raiders cut him down and left.

The next day, twelve-year-old Mary Alice Rice found Carver with his feet blistered from the bushwhackers’ torture. It was an image that stuck with her the rest of her life (she lived until 1949). The war was just as troubling for her as for Carver. She saw dead and wounded men as the opposing forces fought back and forth over Southwest Missouri, leaving the landscape and most of the towns devastated. Rice’s own home was burned twice during the war. One day, she was trapped at school because of a firefight on the road to her home.

But in May 1865, the war was finally over. Missouri had adopted a new constitution that would free the Carver’s slaves on July 4, and the Thirteenth Amendment freeing slaves everywhere was quickly being voted on by the states.

Unfortunately, the violence continued. A group of bushwhackers once again visited the Carver farm. Moses and Jim were able to hide in a brush pile, but the raiders took Mary and young George. Moses thought they may have gone to Arkansas, but as a fifty-two-year-old civilian, he was hardly in a position to track them down.

Moses turned to a former soldier, John Bentley, for help. Bentley, a carpenter born in Leicester, England, had been a sergeant in the Eighth Cavalry, Missouri State Militia (MSM). The MSM’s primary mission was to hunt down guerrillas, thus freeing other troops to join Union armies fighting conventional Confederate forces elsewhere. Bentley spent part of the war as one of the regiment’s “most active spies.” He was captured by guerrillas in October 1862 but apparently managed to escape. Bentley’s military career was sidetracked in January 1865, when he was arrested for murder, but he was released two months later, without any apparent ill effects, by order of the general commanding the district. He was mustered out in April.

Bentley disappeared into Arkansas. He returned a few days later, but he was only partially successful. Mary was nowhere to be found, perhaps even dead. Bentley was able to recover the baby. The guerrillas were either willing to give him up or abandoned him, possibly because George was a sickly boy who was suffering from the whooping cough and the croup. As a reward for finding George, Moses gave Bentley a racehorse said to be worth $300.

Moses Carver’s experience—even being hung from a tree to extract information—was not unusual. After the Confederate army left Missouri, its place was taken by bands of guerrillas, recruiters seeking men to join the conventional forces in Arkansas and cavalry striking in quick raids. Mary Alice Rice’s experience was not atypical either. Although guerrillas and soldiers prided themselves on the protection of women—at least white women—from violence, that supposed solicitude did not prevent them from killing their husbands and sons in front of them or looting and burning their homes. And the slave Mary’s story was not uncommon. Before the war, she was not allowed to live with her husband, her children belonged to her master and her ultimate fate is unknown but likely ended in violence.

Missouri was a battleground—over one thousand engagements were fought in the state (the third most during the Civil War)—but it was also a homefront. St. Louis was a major military base and transportation center. It was filled with Union soldiers and sailors on their way south and with the sick and wounded returning north. Jefferson City was a rude, muddy town that housed an unelected and increasingly unpopular state government. Kansas City was a Union island surrounded by guerrilla strongholds. The countryside was up for grabs, suffering from the depredations of bushwhackers and soldiers alike. And Missouri was still a slave state in a war that came to be as much about emancipation as preserving the Union. It was a turbulent, dangerous place to live.