Interior of Red Cross House at U.S. General Hospital #16, New Haven, Connecticut, c. 1918

Dr. Loring Miner was a country doctor in rural Kansas who practiced an entirely different kind of medicine from that which we have today. He lived far from the nearest hospital, at a time when the machinery of modern medicine was simply unimaginable. Despite the technological limitations of his era, Dr. Miner played a critical role in the story of the 1918 epidemic.

In 1918 Miner had a vast office. His rural medicine practice covered 850 square miles of flat farmland that was nurtured and harvested by 1,720 potential patients. Haskell County, a perfect square of land in southwest Kansas, was 200 miles west of Wichita. In January and February of 1918, as farmers hunkered down in their houses, Dr. Miner observed dozens of cases of severe influenza, or what he called “a disease of undetermined nature.” In one day alone, eighteen people fell ill. Three died. In a sparsely populated county like Haskell, this was remarkable enough to prompt Dr. Miner to write a report to health officials. It was the first recorded instance of a physician warning about an outbreak of influenza. We are far from sure, but Haskell County might have been ground zero for the 1918 flu epidemic in the United States, and perhaps in the world.

Three hundred miles to the east was the U.S. Army’s Camp Funston. Soldiers from the camp visited family in Haskell County at the height of its influenza epidemic and returned to base in late February 1918. On March 4, the first soldier at Camp Funston fell ill with influenza. As soldiers moved freely between Funston, other army camps, and the civilian world, the virus expanded outward in waves. It reached France first at Brest, the largest point of disembarkation for American troops, and on it spread. These facts support the hunch (but it’s only a hunch) that the worldwide flu pandemic of 1918 originated in the American heartland.

The evidence points to two other possible ground zeros. The first was France. John Oxford, a virologist from the University of London, noted that in 1916 there was an outbreak of influenza at a British Army camp in Etaples, in northern France. Two months later an almost identical epidemic broke out at an army camp in Aldershot, England, headquarters of the British Army. One-quarter of the patients there died, and doctors noted similarities to the outbreak in France. Oxford pointed out that two years later, and within a short period of time, there were reports of flu outbreaks in countries that were very far away from one another. Norway, Spain, Britain, Senegal, Nigeria, South Africa, China, and Indonesia were all hit between September and November 1918. International air travel had yet to connect the world, so how did the virus spread so quickly? Oxford reasoned that it must have been “seeded” in these places much earlier, perhaps by demobilized soldiers returning home across Europe during the height of World War I in the winter of 1916.

Did the 1918 flu virus originate in France at the Etaples camp, or elsewhere, like Kansas? John Oxford pointed to photographs of French soldiers in contact with live pigs, chickens, and geese, but this doesn’t prove that they were the source. Perhaps the origin was on the other side of the world, in China.

In June 1918 the New York Times reported that “a curious epidemic resembling influenza is sweeping over North China,” with about 20,000 new cases reported. This epidemic predated the general outbreaks in Europe and America by a few months, and killed fewer people. The population seemed to have some immunity because of a previous exposure to a similar virus. Could a precursor to the 1918 flu have been circulating in China for several years before becoming a global pandemic? There was certainly a route for the virus to have spread from China to France. During the war, more than 140,000 Chinese laborers were recruited to France, and many were stationed near Montreuil—less than seven miles from the British Army’s camp at Etaples. Mankind’s dramatic movement around the globe was good news for an aspiring virus.

As the war in Europe entered its fourth year in 1918, many countries censored news reports, especially those containing information about a pandemic. There was enough bad news from the war without further depressing anxious citizens and soldiers. But Spain remained a neutral country throughout the war, so its press was free to report on the new influenza. This led people to think that Dr. Miner’s “disease of undetermined nature” had started there. While scientists today continue to sort through origin theories, all agree on at least one point: what would be called “the Spanish influenza” certainly did not first erupt in Spain.

So where did the 1918 virus begin? Haskell County, France, or China? Knowing this might help prevent similar outbreaks in the future, but we still haven’t figured it out. There is evidence to support each theory, but as the 1918 pandemic recedes into history, it is unlikely that we will ever come to a definite conclusion. This shiftiness, this uncertainty and mystery, are hallmarks of the flu’s campaign against humanity.

Just as important as its origin and path were the details of its devastation. The world had yet to develop a treatment or discover antibiotics, and the consequences of influenza were extreme and unpredictable. How did this virus move, and what was it capable of ? The answers to both questions are found on the bloody battlefields of Europe.

The virus attacked in two waves. The first began in the spring of 1918, as more than 110,000 U.S. troops deployed to the European front. It had been three and a half years since Britain and France had declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary. Fighting now engulfed all of Europe. President Woodrow Wilson had declared in 1914 that the United States would follow a policy of “strict neutrality,” but this became increasingly untenable as German submarines targeted American ships. Starting in 1917, the U.S. Army sent vast numbers of young men across the Atlantic into large, cramped camps that served as a perfect environment for the influenza virus. In the summer of 1918 the crowding became lethal. Influenza had mutated and young adults were particularly at risk. Soldiers lay within arm’s reach of one another in vast sick wards, separated by nothing more than a hanging sheet.

Interior of Red Cross House at U.S. General Hospital #16, New Haven, Connecticut, c. 1918

This may explain why enlisted men died in much higher numbers than did civilians, despite an equal rate of infection. Most soldiers who were very sick were moved to these crowded wards, where they propagated the bacteria that caused fatal secondary infections. Instead of bringing patients back to health, these wards were large-scale petri dishes of disease.

The virus was not limited to the barracks and sick bays. Across Europe, tens of thousands of men were moving back and forth between home, army camps, the docks, and the war front. The U.S. War Department was sending 200,000 men a month to France. By the summer there were more than 1 million American soldiers fighting in Europe.

We do not know how many civilians became ill and died in that first wave. At that time there was no requirement for doctors to report anything about the flu. There were few state or local health departments, and those that existed were often poorly managed. However, we can get a sense of what happened by looking at statistics kept by the military. Starting in March 1918, there was a sudden increase in the number of influenza cases seen at Camp Funston in Kansas. Most of the troops recovered after two or three days of bed rest and aspirin, but 200 contracted pneumonia and around 60 died. In a sprawling camp of 42,000, these numbers did not make military physicians notice.

The situation in Europe was more drastic. One medical officer noted that influenza was raging through his division. His soldiers weren’t able to march. By spring some 90 percent of the troops in the American 168th Infantry Regiment were sick with the flu. By June 1918 it had spread to French and British troops. There were more than 31,000 cases of influenza among British troops back in the UK, a sixfold increase over the previous month. On the European continent, over 200,000 British troops were unable to report for combat. The virus continued to travel, usually by sea. It struck Freetown in Sierra Leone after a British steamship arrived in August with more than 200 of its crew enduring or recovering from influenza. In less than a week it had spread overland; before the end of September some two-thirds of the local population had become infected and 3 percent had died. Outbreaks were reported in Bombay. In Shanghai. In New Zealand.

This first wave was mild. Although many people became sick, the disease lasted only two or three days. Nearly everyone recovered. As usual, those who were most at risk were the very young and the elderly, whose mortality was much higher than the general population. But epidemiologists who examined death records noted that there was an increased incidence of death in the population between these two extremes. Young and middle-aged adults were dying from influenza at an unusually high rate.

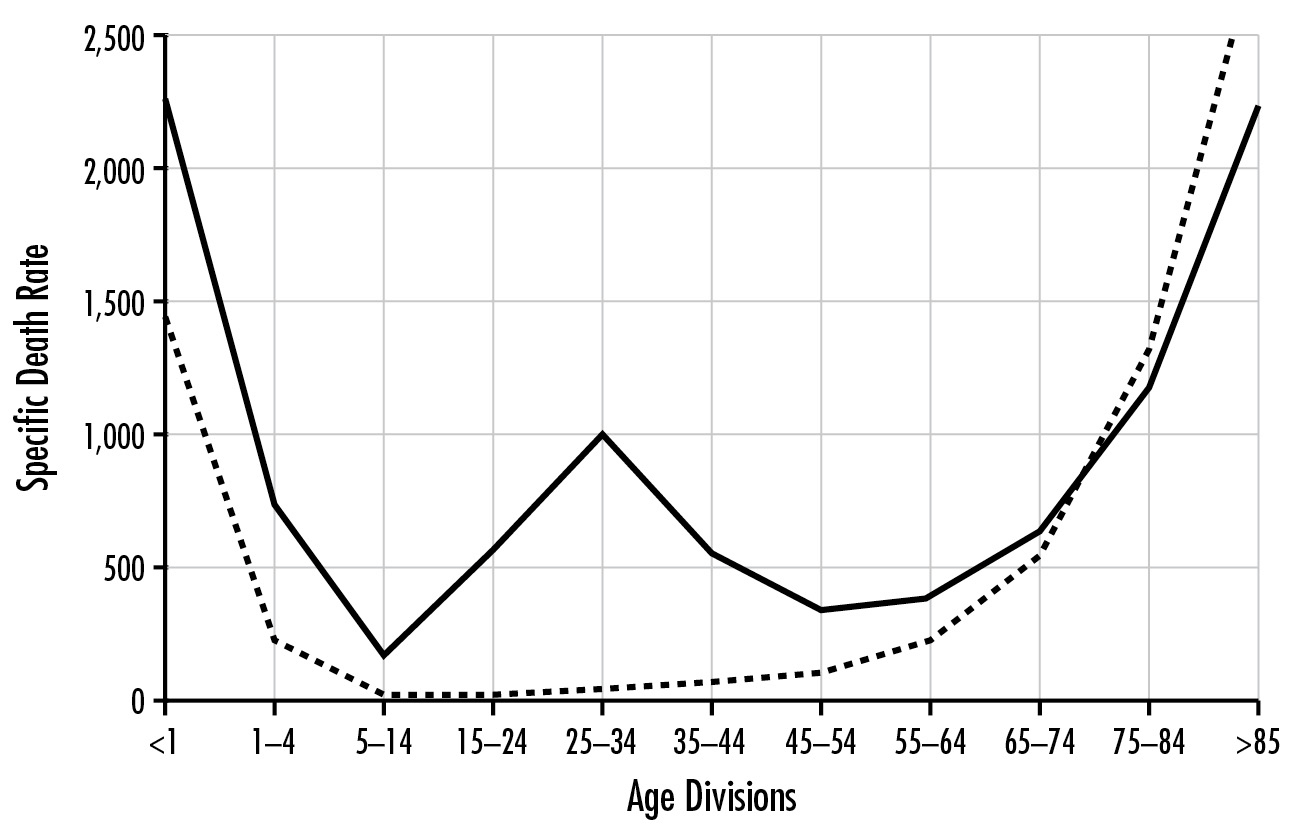

When plotting influenza deaths against age, we most commonly see a U-shaped graph; one arm represents the very young and one the very old. In the middle, there are very few deaths. The same graph of the early 1918 deaths from the flu is shaped like a W. There still existed the high death rate at either end, but there was an additional spike that represented the young and middle-aged. Those most affected were in the twenty-one- to twenty-nine-year-old age range, a group usually considered to be the least likely to die from an infectious disease. This was peculiar and alarming.

Influenza and pneumonia mortality by age, United States. Influenza and pneumonia specific mortality by age, including an average of the interpandemic years 1911–1915 (dashed line), and the pandemic year 1918 (solid line). Specific death rate is per 100,000 of the population in each age division. Institute of Medicine. The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Stacey L. Knobler, Alison Mack, Adel Mahmoud, and Stanley M. Lemon, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005, 74.

By the time the first wave of flu hit the European continent it had virtually disappeared in the United States. In time, the numbers decreased in Europe too. By July 1918 the British Medical Journal reported that influenza was no longer a threat. But on both sides of the Atlantic the worst was still to come.

* * *

Perhaps the virus had mutated into a more lethal form. Perhaps the autumn brought people into closer proximity, where they were more likely to infect one another. Regardless, another wave of influenza began.

Among the earliest reports of the second wave was one from Camp Devens, some thirty miles west of Boston. The camp, built for about 36,000 troops, now housed more than 45,000. The outbreak began around September 8 and rapidly spread. Ninety patients a day came to the camp infirmary. Then 500 a day. Then 1,000 men each day, stricken with the flu. The infirmary was large, built to treat up to 1,200 patients. Soon it was not large enough. Eventually it housed 6,000 influenza victims. Bed after bed. Row after row.

“We eat it, live it, sleep it and dream it, to say nothing of breathing it 16 hours a day,” wrote a young medical orderly in a letter dated September 29, 1918. He was assigned to a ward of 150 men, and his first name, Roy, is all we have to identify him. The grippe—another name for influenza—was all anyone could think about. One extralong barracks had been converted into a morgue, where dead soldiers dressed in their uniforms were laid out in double rows. Special trains were scheduled to remove the dead. For several days there were no coffins, and Roy wrote that the bodies piled up “something fierce.” The orderly witnessed countless deaths, and he described what happened to the victims. Although it started as just another case of influenza, the infection rapidly developed into “the most vicious type of Pneumonia that has ever been seen.” There were about 100 deaths each day at the camp. Among these were “outrageous” numbers of nurses and doctors. “It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle,” Roy wrote. He had witnessed the devastation and mayhem of the Great War, and still, there was no comparison. The flu was far worse.

Another eyewitness account of the carnage at Camp Devens was provided by Victor C. Vaughan, a prominent physician and dean of the medical school at the University of Michigan. In his memoir he wrote of ghastly pictures that hung in his mind, “which I would tear down and destroy were I able to do so, but this is beyond my power.” One of those memories was of the division hospital at Camp Devens. “I see hundreds of young, stalwart men in the uniform of their country coming into the wards of the hospital in groups of ten or more,” he wrote. “They are placed on the cots until every bed is full and yet others crowd in. The faces soon wear a bluish cast; a distressing cough brings up the blood stained sputum. In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood.” Vaughan was humbled by a plague he could not treat. “The deadly influenza,” he concluded, “demonstrated the inferiority of human interventions in the destruction of human life.”

Less than a month after it began, the flu epidemic at Camp Devens had sickened 14,000 and left 750 dead. It swept across other military bases. Camp Dix in New Jersey. Camp Funston in Kansas. Camps in California and Georgia. At Camp Upton in New York, almost 500 soldiers died. The flu was brought to Camp Dodge in Iowa by two servicemen who arrived on September 12. Six weeks later more than 12,000 men in the camp had been infected. At one point the infirmary housed over 8,000 patients, four times its maximum capacity.

The outbreaks at each camp followed a pattern. First there were just a handful of cases, indistinguishable from a regular season of influenza. Within a couple of days the number grew exponentially, infecting hundreds, sometimes thousands. For three weeks the infirmaries were flooded and the death toll would rise. After five or six weeks the epidemic would disappear, as mysteriously as it had arrived. Some victims lingered with pneumonia, but there were no new cases, and life would slowly return to normal.

A great deal is known about flu in the army camps because of the record-keeping that the military required. But the second wave of flu struck beyond the military, killing tens of thousands in towns and cities across the United States. This wave is more challenging to piece together; nonetheless, by the time it subsided in the late spring of 1919 the death toll in the U.S. stood at 675,000 civilians and service members. The sheer amount of death is hard to fathom, and the spread of the disease nearly defies the imagination. Almost every town and city was affected.

* * *

In 1918 Philadelphia had a population of more than 1.7 million people. Like in most growing cities in the early twentieth century, its inhabitants were packed together in narrow tenement buildings. They were especially vulnerable to influenza because most of Philadelphia’s doctors and nurses were overseas, tending to the wounded and the battle weary. As the flu struck, the few medical professionals left in town were stretched very thin. They were not prepared for what was to come.

Influenza probably snuck into Philadelphia in the middle of September 1918, around the time newspapers reported that the virus had made the leap from army camps to civilian neighborhoods. Spreading just as fast were rumors that German submarines loaded with germs were causing the outbreak. They weren’t, but the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard likely was.

With a complement of 45,000 sailors, the yard had grown to become the largest naval base in the U.S. On September 7, 1918, the base welcomed 300 sailors who had been transferred from Boston. It is highly likely that a few of them were incubating the flu virus. Two weeks later, more than 900 sailors were sick. Officials stuck to a script: There was little to fear. The flu was nothing other than the usual seasonal germ masquerading under a new name.

But the virus was about to make a jump to civilians in a big way, and war bonds were partly to blame. Back in April 1918, a huge Liberty Bonds parade had taken place in New York City. The movie star Douglas Fairbanks addressed the masses who stood shoulder to shoulder. With his good looks and charming personality, he urged them to buy bonds to support the war effort. Five months later, it was time for Philadelphia to step up. The city planned its own war pageant to inaugurate the fourth Liberty Loan campaign on Saturday, September 28. It expected 3,000 fighting men, “and fighting women if need be,” according to an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer. They would be joined by hundreds of factory workers and marshals who would keep the crowd singing together. All this was planned amid the city’s flu epidemic. If there was any concern that such a large gathering would enable the flu to spread, it was overcome by the patriotic desire to participate.

The war-bond parade was essentially a marching band of influenza. The navy came down Broad Street as huge crowds looked on and cheered.

“It was a tremendously impressive pageant,” declared the Inquirer, which estimated that more than 100,000 people thronged the streets. As people stretched their necks for a better view, they were also transmitting the flu virus person to person. The Liberty Bonds march had actually liberated the virus.

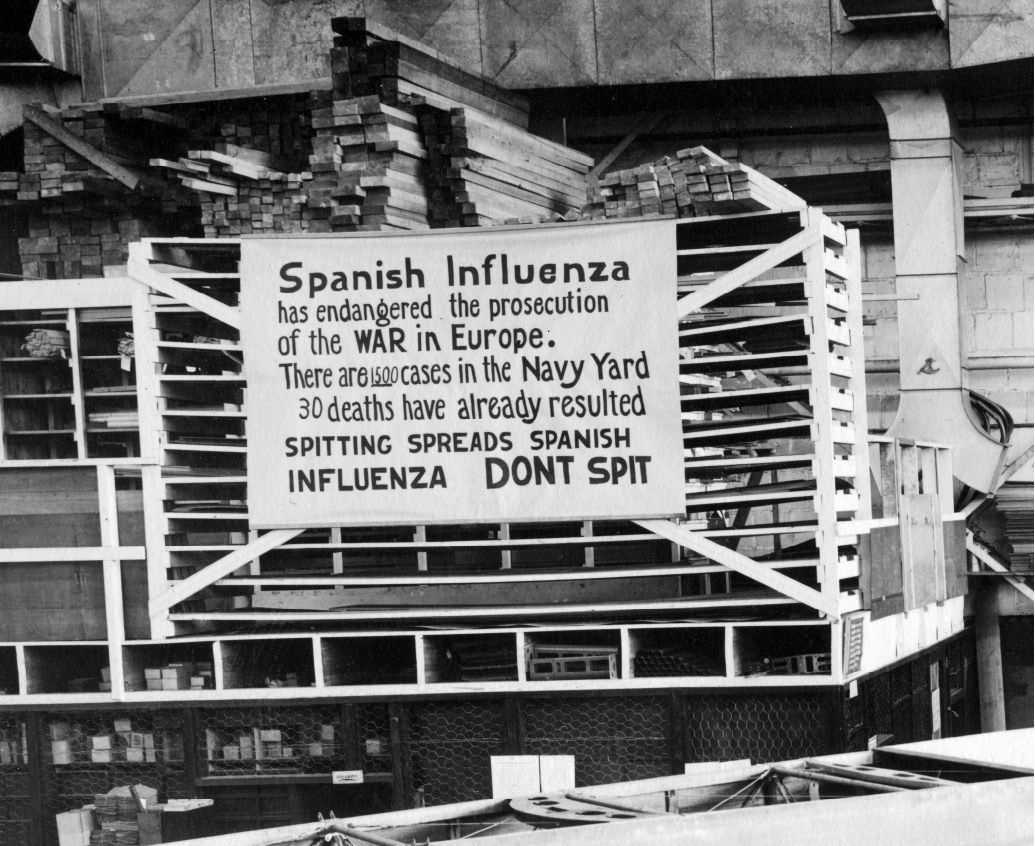

Only two days after the glorious parade, more than 100 people each day were dying from flu. In short order those numbers grew sixfold. Each day, health officials announced that the disease had passed, only to publish more grim statistics the next. The director of Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health, Dr. William Krusen, issued an order to close schools, churches, and theaters. Perhaps if he had prohibited the Liberty Bonds march, the situation would not have been so dire. Placards reminded everyone that spitting on the streets was not allowed. They didn’t do much good. In one day alone, sixty spitters were arrested.

Naval Archive

With so many people taken ill, courts and municipal offices were closed and other essential services struggled without their employees. The police and fire departments were hobbled by diminished ranks. Because of severe staff shortages, Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania announced that it could handle only calls that were “compelled by the epidemic or by war necessity.” With its regular hospitals over capacity, the city opened an emergency one. Within a day, all five hundred of its beds were full. Krusen called for calm and urged the public not to panic over exaggerated reports, but Philadelphia was being ravaged by what seemed like a biblical plague. Why not panic?

The only public morgue in the city had the capacity to hold thirty-six bodies. It soon held hundreds of corpses, most covered only with bloodstained sheets. For each available coffin, ten bodies lay waiting. The stench of death was everywhere. Local woodworkers dispensed with normal business and began making coffins full-time. Some funeral homes increased their charges by over 600 percent, prompting the city to cap premiums at “only” 20 percent.

The death toll in Philadelphia peaked around the middle of October and then, almost as suddenly as it had arrived, the plague subsided. Flu was still present, to be sure, but deaths from influenza fell back to their usual rates. The city slowly returned to a semblance of its former healthy self.

Historic chart of influenza death rates in New York, London, Paris, and Berlin, 1918–1919 From the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C.

What happened in Philadelphia was repeated across the United States, and the world. In San Francisco, the flu also peaked in October. More than 1,000 people died that month, almost double the usual number. The flu made it to Juneau, Alaska, which tried to prevent its spread by imposing a quarantine. The governor ordered that all disembarking passengers be examined by dockside physicians. Any person showing symptoms of the flu was refused entry to Juneau. This did not, however, prevent the entry of healthy-looking people who were carrying the virus but not yet showing symptoms. These carriers left Seattle and docked in Juneau a couple of days later, still within the flu’s incubation period. When they arrived, they were briefly examined by a waiting physician, who, finding no signs of influenza, allowed them entry. This is the most likely way the virus snuck in. From there it spread to Native Americans in Nome and Barrow and dozens of remote villages. The devastation among tribes was even more profound than it was elsewhere. They were naturally isolated from the rest of the population and therefore lacked any antibodies to influenza. Half the population of Wales, a town of 300 on the west side of Alaska, was killed in the 1918 pandemic. In the tiny settlement of Brevig Mission, population 80, only 8 people survived.

This horror near the Arctic Circle would, in the long run, help fight the virus. The dead were buried in the frigid ground, and this resting place of permafrost preserved the bodies. Eighty years later, this allowed scientists to extract samples of the 1918 virus and, for the first time, identify its genetic code. For now, though, those bodies would lie in wait, frozen in earth and in time.

* * *

America was now fighting two wars. The first was against Germany and its military allies. The second was against the flu virus and its bacterial allies. In the words of one historian, it was a fight against germs and Germans.

As the Allies mounted a massive offensive on the western front, influenza attacked the ships transporting troops to the trenches of Europe. It killed many in the American Expeditionary Forces at the height of the Battle of Argonne Forest, in northeastern France. Just as the Great War entangled nearly every country in Europe, influenza ravaged the whole continent. At one French army base of 1,000 recruits, 688 were hospitalized and 49 died. Schools were closed in Paris, but not theaters or restaurants. Cafes stayed open as 4,000 Parisians died. Influenza leaped trench lines. German troops suffered too. “It was a grievous business having to listen every morning to the chiefs of staffs’ recital of the number of influenza cases, and their complaints about the weakness of their troops if the English attacked again,” wrote one German commander at the time.

In Britain, it was very much a “keep calm and carry on” approach. I was born and grew up in London, and even though I have now lived outside of Britain for most of my life, I recognize this reaction. Composure in the face of adversity and keeping a stiff upper lip were hallmarks of my childhood. I had seen such composure on the face of my grandmother as she recalled being evacuated from London during the Blitz, and I recognized it in the reaction to the Spanish flu a generation before. “Keep calm and carry on” were not just instructions for public behavior. They were part of the cultural DNA of the British themselves.

At first the newspapers barely mentioned the epidemic; when they did it was buried on the inside pages. The British government and a sympathetic press tacitly agreed to limit any discussion of the flu, lest it demoralize a public already weary of a world war entering its fourth year. The tension between reporting the facts and maintaining morale was embodied in a letter written by a Dr. J. McOscar that was tucked away in the back of the British Medical Journal.

“Are we not now going through enough dark days, with every man, woman, or child mourning over some relation?” he wrote. “Would it not be better if a little more prudence were shown in publishing such reports instead of banking up as many dark clouds as possible to upset our breakfasts? Some editors and correspondents seem to be badly needing a holiday, and the sooner they take it the better for the public moral [sic].”

Ironically, there was a detailed five-page report on influenza on the front page of the same issue in which this letter appeared. It underscored just how devastating the pandemic was. There had been a catastrophic outbreak among British and French troops, it noted, that had swept through entire brigades and left them unable to function.

Britain’s chief medical officer also seemed reluctant to upset anyone’s breakfast. His advice was limited: wear small face masks, eat well, and drink a half bottle of light wine. The Royal College of Physicians took a similar approach and announced that the virus was no more deadly than usual. The British seemed relatively unmoved throughout the saga. In December 1918, as the pandemic was ending, the Times of London commented that “never since the Black Death has such a plague swept over the face of the world; never, perhaps, has a plague been more stoically accepted.”

Earlier that year, the medical correspondent for the Times, with what must have been a huge exaggeration, described a people who were “cheerfully anticipating” the arrival of the epidemic. The historian Mark Honigsbaum believes that this British stoicism was deliberately encouraged by the government, which had already worked to cultivate a disdain of the German military enemy. The same disdain was then directed at the influenza outbreak.

But whatever the attitude of the British toward the pandemic, influenza’s toll was enormous. By the time it had subsided, more than a quarter of their population had been infected. Over 225,000 died. In India, then still a British territory, influenza was more lethal, with a mortality rate above the Empire’s 10 percent. It was double that among Indian troops. In total, some 20 million Indians died as a result of the influenza pandemic.

Then there were Australia and New Zealand and Spain and Japan, and countries throughout Africa. All suffered, leaving us with that frightening, near-apocalyptic estimate: 50 million to 100 million deaths worldwide, in total. In the aftermath of this mass death—when the public was focused on “How?” and “How many?”—scientists were left to wonder: Why?

Was it the virus itself—perhaps a super version of the flu—or were there other reasons for its lethality? We’ve settled on four different explanations for why so many people died. Each is supported by some evidence, yet none is wholly satisfying.

The first explanation is that the virus had a protein on its surface that prevented the production of interferons, which signal to our immune system that our defenses have been penetrated. Healthy lung cells that transfer oxygen into the bloodstream are hijacked by the virus and destroyed by its replication process. Once dead, these cells are replaced with dull fibrous ones that are incapable of transporting oxygen, just like a scar that forms at the site of a cut and never looks the same as the surrounding healthy skin. An autopsy performed within hours on a U.S. Army private named Roscoe Vaughan in South Carolina showed that one of his lungs had this type of pneumonia. It’s possible that the sabotage of interferons allowed the 1918 virus to trigger a lethal viral pneumonia.

Second, if the 1918 virus itself didn’t kill you, then secondary bacterial pneumonia probably did. Victims of the pandemic, their bodies weakened and their lungs already ravaged, caught bacterial infections like streptococcus and staphylococcus, which were deadly in this era before antibiotics. We now think that the majority of deaths in the 1918 pandemic resulted from these secondary infections, not from the flu virus itself. The South Carolina soldier’s other lung showed evidence of this kind of infection. He was killed by the one-two punch of the virus and a bacterial infection that swept in as his defenses crumbled.

The third explanation for 1918’s lethality is that the flu virus triggered an overreactive immune response that turned the body against itself. Suppose you cut your finger. Bacteria invade and infect the wound. Your finger becomes swollen, red, and warm because of increased blood flow to deliver more white blood cells to fight the bacteria. This inflammation, a painful but necessary development for fighting infection, is mediated by other kinds of messenger proteins called cytokines. Once the infection is overcome, cells stop producing cytokines and the immune system returns to its usual state of vigilance.

This return to normal didn’t happen in many 1918 flu victims. Their lungs were hit by a “cytokine storm,” an overproduction of these messenger proteins. In their exuberance, they began to destroy healthy cells along with invading ones. When a cytokine storm strikes, the immune response spirals out of control. The storm activates more immune cells, which release more cytokines, which activate more immune cells, and on and on. Large amounts of fluid pour out of the war-torn lungs. Healthy air sacs in the lungs scab over. It becomes harder and harder to breathe.

It’s unclear why this storm occurred in some victims and not in others, or why it may have been especially common in those between twenty and forty years old. Infectious disease experts have called this the biggest unsolved mystery of the pandemic. If we solve it, we might be able to protect ourselves from another fatal plague of flu.

The fourth explanation points to the circumstances that surrounded the flu’s transmission. It was a novel virus, having originated in birds. The virus then spent some time in another host, perhaps pigs or horses, until it emerged as a threat to humans. This occurred at a time when people were both penned in together—living in tenements or barracks—and unusually mobile, as the Great War circulated infected soldiers around Europe and beyond. Working-class families shared beds. Soldiers slept side by side in cots and traveled the world in steerage conditions. Had these human mixing bowls not existed, the flu virus, however lethal, would not have spread so quickly.

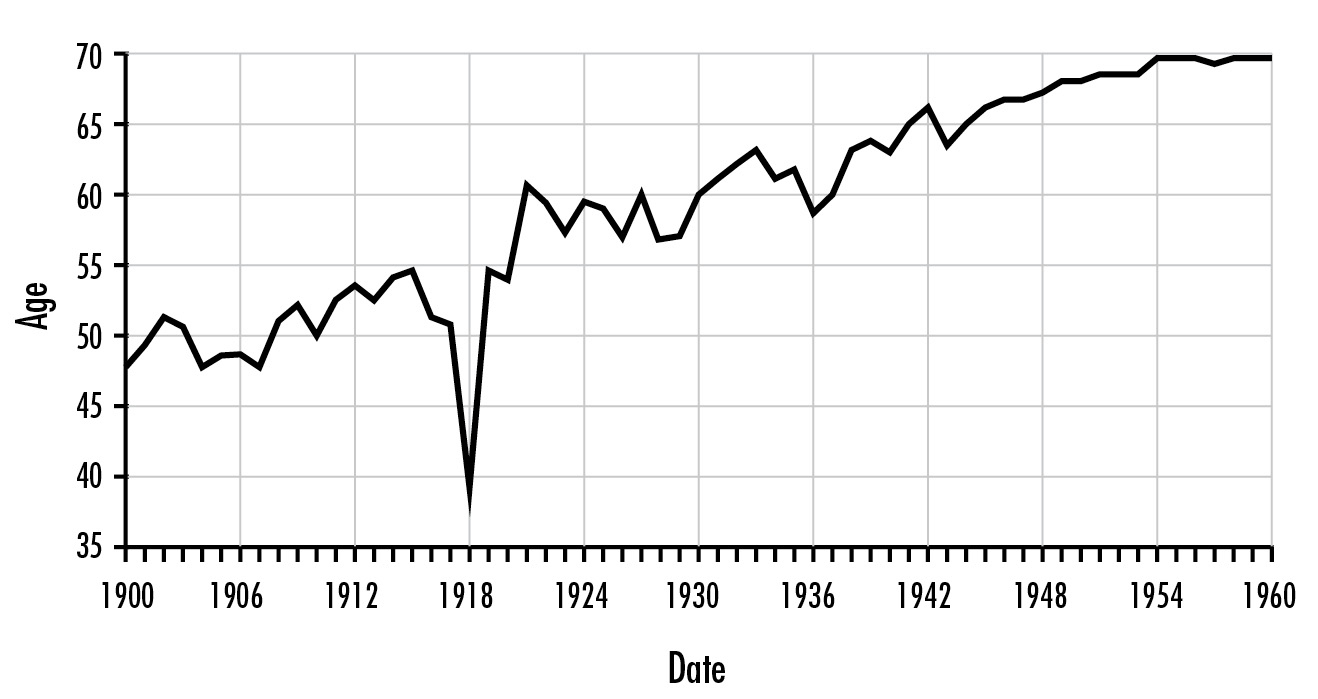

Today, influenza kills fewer than 0.1 percent of those who catch it. Nearly everyone recovers. In the 1918 pandemic most still recovered, but the death rate was twenty-five times greater. So many died in the U.S. that the average life expectancy in 1918 fell from fifty-one to thirty-nine years.

Life expectancy in the United States, 1900–1960, showing the impact of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Institute of Medicine, The Threat of Pandemic Influenza.

In December 1918, in the midst of the pandemic, 1,000 public health officials gathered in Chicago to discuss the plague, which had killed an estimated 400,000 people over a three-month period. Some were already predicting that the following year there would be an even more virulent flu outbreak.

Dr. George Price, one of the attendees, described the state of affairs in his report. It makes for terrifying reading.

First, the doctors admitted that they didn’t know the cause of the pandemic. “We may as well admit it and call it the ‘x’ germ,” Price wrote, “for want of a better name.” Physicians had identified several distinct microorganisms in the secretions of the victims, but were they the cause or were they opportunistic hijackers of a body already beset by disease? (The latter, it turned out.)

Attendees at this conference did agree on a few things. Whatever transmitted the disease was found in the spray and mucus from the throat, nose, and mouth. It could be spread through droplet infection by sneezing and coughing, and by hand-to-mouth contact. This prompted one physician to suggest that the only way to reduce the spread was to put “each diseased person in a diver’s suit.”

Doctors also agreed that if you recovered from this influenza, you emerged with a certain degree of immunity. Many people over forty years old were spared. The theory then, as now, was that this demographic—those who had lived through a severe influenza epidemic in 1898—had acquired immunity against the 1918 infection.

But how to control the disease? The conference erupted into heated discussions inflamed by a general despair. The flu had spread despite precautions to combat it, and then it had suddenly and unexpectedly disappeared. Face masks, which were then being worn by a large number of the general public, were no guarantee of protection. Many health officials believed they provided a false sense of security. Perhaps that was true, but there was still a value in providing any kind of security. Chicago’s health commissioner made this clear. “It is our duty,” he said, “to keep the people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic. For my part, let them wear a rabbit’s foot on a gold watch chain if they want it, and if it will help them to get rid of the physiological action of fear.”

Officials tried to collect data on the sick and the dead, but many states were still not required to report their cases. Physicians on the front lines of the disease were too busy to fill out the necessary paperwork, and plenty of victims died before they ever came in contact with the medical system. It was thus nearly impossible to estimate the number who had died, or had been infected and recovered. The virus snatched people before they could even be counted. No mechanisms existed to render the monstrous plague in practical, numerical terms.

During the bubonic plague of London in the 1600s, many afflicted households painted a large cross on their front door, along with the words “Lord have mercy on this house.” It warned that illness and death lurked inside. Something similar happened in 1918—but in a more regimented way—with “placarding,” the posting of signs on front doors. Placarding was supposed to warn healthy people to stay away, but in many communities almost every household door was marked.

There was also a public health effort to reduce crowding and mixing in public spaces by closing schools, theaters, and stores. It was a way to force people to spend their leisure time resting, to store up energy and stave off infection. But it was not clear whether these closures actually helped. Detroit shuttered very few public spaces and suffered only a relatively minor outbreak, while Philadelphia instituted a much tougher closure policy that didn’t prevent a health catastrophe. Royal Copeland, the president of the New York Board of Health, changed the schedule of buses and subways to combat overcrowding. He installed large signs around the city that reminded the public not to spit. But he did not close schools or theaters; he argued that because many schoolchildren lived in crowded tenements they would be better off in school, where they could be taught how to stay healthy.

Dr. Price’s description of the 1918 conference in Chicago ended with a clarion call to action. Despite great uncertainty and a degree of despair, he maintained that the best way to end the influenza epidemic was through public health policy. There needed to be better coordination between the health agencies, which should be placed under a unified command, like the military. To beat the enemy, private and community institutions needed to work together, at the municipal, state, and federal levels. Price knew he was asking for the moon. The virus required nothing less. Among the symptoms of influenza was something more pernicious than a fever or shortness of breath. It was a feeling of futility, which had a lifelong impact on Victor C. Vaughan, that dean of the medical school at the University of Michigan. Having witnessed the deaths of so many, Vaughan decided “never again to prate about the great achievements of medical science and to humbly admit our dense ignorance in this case.”

* * *

The history of the 1918 influenza pandemic is depressing reading. It’s like watching a horror movie that you have seen before. You know who the killer is, but you can’t jump in and save the victim. However, during the pandemic and in the years that followed, there was a steady stream of dramatic medical discoveries that would, for the first time, allow us to fight back against the flu.

Some medical professionals were so desperate to identify what it was that caused influenza that they placed their own lives in peril. In the winter of 1918–1919, at the height of the flu epidemic, about 30 million Japanese became ill and more than 170,000 of them died. Despite this, a professor named T. Yamanouchi was able to find fifty-two doctors and nurses who offered to help by becoming human guinea pigs. The professor took “an emulsion of the sputa” from influenza patients and placed it in the noses and throats of this group of volunteers. Some received this contaminated goop directly, while others got it after it was run through a filter whose mesh was fine enough to capture all bacteria. Both groups soon exhibited signs of influenza, which led the Japanese researchers to affirm that no known bacteria could be the cause of influenza. In addition, they concluded that the disease could be spread by getting into the nose or throat of its victim, a feature of flu that we now take for granted but was barely recognized at the time.

There have always been researchers willing to experiment on themselves. The Australian physician Barry Marshall is a recent example. He co-discovered the bacteria that cause stomach ulcers. In order to prove this, Marshall himself agreed to drink a sludge containing the bacteria and see what happened. He got stomach ulcers. And a Nobel Prize. But the courage of those Japanese volunteers in 1918 was even more remarkable. All around them an epidemic was killing its victims in unprecedented numbers, and there was no known cause or cure. Yet fifty-two doctors and nurses agreed to be inoculated with material from those who had been infected. They were prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice. Their bravery and generosity almost defies belief.

The Japanese discovery was quickly replicated. In 1920, two American researchers also developed a filter small enough to remove all known bacteria from nasal washings taken from those with influenza. Yet the remaining material was still able to cause influenza-like symptoms when given to live rabbits. Again, the conclusion was that bacteria could not be the cause of influenza. Soon there were reports of other illnesses that were caused by agents too small to be stopped by a bacteria-catching filter. The cause of the pandemic was still a mystery, but we had eliminated bacteria as a suspect.

So what was getting through those bacterial filters? It was, of course, the influenza virus. In 1933 two British scientists—working at a laboratory in north London only a few miles from where I grew up—demonstrated that they could infect ferrets with samples obtained from the throats of patients that had been filtered to remove all bacteria. (It turns out that ferrets are one of the few mammals that get sick with influenza. They are also easier to work with than pigs.) This built on the work of the Japanese group, and the British scientists concluded that “epidemic influenza in man is caused primarily by a virus infection.” Another important advance in the same decade was the discovery that the influenza virus could be cultivated. It was injected into the amniotic fluid of developing chicken embryos, which turned out to be a perfect growing medium for the rather picky virus. This was an incredibly important development. If you can grow the virus, you can also collect it, kill it, and inject it into healthy people. And then you have a vaccine.

Finally, in 1939, there was a watershed moment in the history of virology. The newly invented electron microscope took a picture of a virus. For the first time in history we could actually see the culprit. By the 1940s, scientists had isolated two strains of influenza (A and B) and begun to test vaccines; one of these scientists was Jonas Salk, who later developed the polio vaccine. After Crick and Watson’s discovery of DNA in 1953, it didn’t take long to identify the various building blocks of a virus. The field of virology could then develop tools and techniques to identify viruses and classify them based on their genetic components.

Medicine is the art of diagnosing, treating, and curing. It is also the art of preventing history from repeating. Did we learn enough from the 1918 pandemic? Could the lessons learned prevent another catastrophe? We now knew what virus we were up against, but could we do a better job of fighting it? The world would be tested again a few decades later, when the next pandemic arrived on the island of Hong Kong.