Saxophonist-turned-pizzaiolo-turned-wine grower, Angiolino Maule is today one of Italy’s most prominent natural wine champions. Owner of La Biancara—an organic wine estate in the Veneto with 30 acres (12 hectares) of vines and 100 olive, cherry, fig, apricot, and peach trees—Angiolino is also the founder and President of VinNatur, Italy’s largest association of natural growers, and a driving force for change in the country.

“Our “mother” is actually over 100 years old. It came from an old baker friend of ours who got it from his father. It’s the same one we used at Sax 54, the pizzeria my wife and I owned and ran for 12 years, before La Biancara. We used it to make the sourdough bases of our wood-fired pizzas. It’ll be passed on to our children and grandchildren as well and, since it is the result of ambient yeasts, with time it will become even more complex.

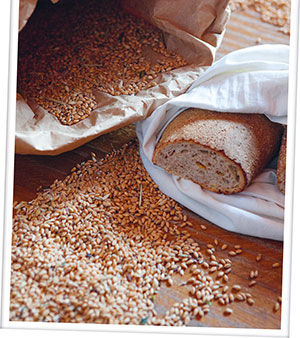

But the secret to great bread isn’t the mother. It’s the germ.

That’s the main difference between our wheat and the sort you’d buy in a shop: ours still has the germ in it. It makes all the difference to the quality, because the wheat is proper whole wheat. Nothing added, nothing removed.

This is only possible if you buy grains, rather than flour. Flour is overly manipulated, ground in industrial quantities, and processed so that it can last for years. It is a shame because one of the most important parts of wheat is the germ. It is this that is full of vitality. It is the embryo of the wheat kernel and is rich in vitamins, minerals, and proteins. The trouble is that if you leave the germ in the flour for any length of time, the flour goes rancid. So, commercial millers separate it out, together with the wheat-germ oil, to conserve the flour for longer. But the result is far less nutritious and tasty.

So buy grains rather than flour. We get ours from a fellow natural-wine-producing friend of ours, in the Piedmont, who grows wheat alongside his grapes. Wholewheat grains can keep for months at a time, so there’s no problem, and we grind as and when we need to, using the freshly ground flour almost immediately.

You used to be able to turn up with a small 5kg sack of grain at a local mill that would grind it for you. But the Italian village mills of old no longer exist. If you turned up at a mill today, out of the blue, I imagine they’d look at you sideways, and I doubt they’d work with quantities that small anyway. So, instead, we have a tiny stone mill at home. It is about the same size as a coffee grinder and crunches up the entirety of the grain so that all the goodness remains, including the bran, which is rich in fiber. The result is bread with a trace of sweetness, even though it is not sweet, which is also much easier to eat, as it’s much more digestible than the breads you normally get your hands on.

We make flour once or twice a week, mainly for bread. It’s easy. All you need is 1.5kg of freshly ground flour, 700ml of water, a pinch of salt, and 100g of sourdough culture (or “mother”), which you can make yourself simply by leaving flour and water (mixed so that it has the consistency of thick soup or porridge) out on the kitchen counter. (You can help kick-start the fermentation by adding a little live yogurt, honey, or a piece of apple, all of which are rich in yeasts—you usually need 2–3 days for a good fermention.) The mixture will then ferment by itself and all you have to do is feed it flour, like a pet.

Mix the flour, water, salt, and mother together so that it is thick. Knead it by hand for about 10 minutes, or until the ingredients are well mixed, and leave it to rise for 48 hours. Then, put it in an oven at 250°C for 30 minutes.

There you have it—bread.”

Using their 100-plus-year-old sourdough mother, together with flour they freshly mill in their home kitchen, the Maules knead the dough, leave it to rise, and bake it. As Angiolino says, “This is something everyone can do at home.”

“How can a nation be great if their bread tastes like Kleenex?”

(THE LATE JULIA CHILDS, AMERICAN CHEF AND AUTHOR)