“We don’t inherit the earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children.”

(ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY, FRENCH ARISTOCRAT, WRITER, AND POET)

Natural growers come from all walks of life. They may have inherited vineyards from their family or come to farming as a second or even third career. They may be a wild child or a wine nerd, conservatives or kids of the French protests of May 1968. Some fight the system, while others end up as poster boys for it; others choose to stay in the shadows doing what they have always done. But, whether they are radicals or traditionalists, they have all, in some way or other, turned their backs on what the majority of the system sees today as the prerequisites for making wine.

What unites this rainbow army of curious bedfellows above all else is a love of the land. They see themselves as custodians of the natural world and remind us that, done correctly, farming is perhaps the most noble of professions, demanding not only incredible skills of observation, but also a respect and humility that the sublimity of nature necessarily commands.

“We even think about the yeasts and bacteria,” explains Jean-François Chêne, from La Coulée d’Ambrosia in the Loire, France. “We try to be close to them, thinking about what they need so that they can be in conditions that are favorable to their work. It’s all a state of mind. And it always comes back to the same rule: pick irreproachable raw material and there’s no need to ask any more questions.”

To grow these “irreproachable” grapes, growers must have an intimate knowledge of their land, which is only possible in the truest sense of being an artisan—a skilled tradesman or woman, working by hand and developing mastery through experience. These growers often work with heritage grape varieties, which are shunned by more commercial growers. “Our goal was to save as many indigenous varieties as possible [from our area] that were on the verge of disappearing,” explains natural grower Etienne Courtois, from the Loire, who works with his father, Claude. On the other side of the world, in Chile, natural grower Louis-Antoine Luyt has focused much of his work on the production of pais. This “workhorse” grape was introduced into the country by Spanish missionaries in the 16th century, but discarded by commercial growers in favor of more fashionable varieties such as chardonnay or merlot, many of which were unsuited to the Chilean climate.

Luyt is also reviving the old Chilean art of fermenting grape juice in a cowhide, with the hairy side facing inward, a practice long since abandoned by all his fellow (adoptive) countrymen. Not only is this, as it turns out, a very efficient mechanism for ensuring healthy ferments, but it is also remarkable for drawing on the kind of ancient wisdom so often dismissed as backward quackery. Be it claypots (such as the Georgian qvevri/kvevri or Spanish tinaja), orange wines, or even hand-harvesting, natural growers often work using traditional know-how. They are the keepers of heritage practices, which, if discarded, would disappear.

Surprisingly, perhaps, natural growers can also be extremely innovative. They are often already outside the system, so tend to think outside the box, too. Take Californian natural grower Kevin Kelley, for example. Concerned by our reliance on unnecessary packaging, Kevin decided to treat fresh wine like fresh milk, setting up the Natural Process Alliance (NPA) project which featured a bottle-exchange program. Every Thursday, Kevin would set off on his “milkround,” delivering canisters of wine (straight from the barrel) to customers in and around San Francisco, swapping full canisters for that week’s empties—the milk bottles of yesteryear.

Matassa’s Romanissa vineyard at sunset.

Two Slovenian natural growers—Branko Čotar (right) of Vina Čotar and Walter Mlečnik (left) of Mlečnik—enjoying a glass of wine together.

This originality of thought also extends to ways of living. “In the countryside, we live very independently. We’re very self-sufficient,” says Olivier Cousin, one of the Loire’s natural-wine-grower pin-ups. “Even though, between harvest et al, I employ 30 paid people a year, I still do a lot of bartering. We exchange wine for meat, vegetables, all sorts. It’s a beautiful community and this solidarity is an integral part of natural wine.”

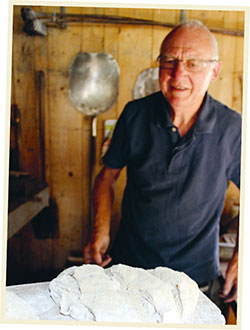

While not all as bon-vivant as Cousin, natural growers are often holistic by nature, thanks to their acute appreciation of the subtleties of proper food, health, and life. They may, for example, be as into honey as wine or also cure saucisson or prosciutto at home. The embodiment of this natural philosophy has to be 80-year-old natural wine legend Pierre Overnoy, from the Jura, in France. As well as baking dozens of loaves of delicious sourdough every week for family and friends, he keeps bees, chickens, and an extraordinary collection of grape bunches, preserved in alcohol, that he has picked every year, on July 2nd, since 1990, in order to compare growing patterns. He is as happy to get down and dirty, planting salads or sorting out the plumbing, as he is to talk microbiology or the intricacies of fermentation. He is above all inspiring: warm, gentle, and generous, and his insights sharp and considered.

Unfortunately, there is a mistaken belief that natural growers are laissez-faire or sloppy, which could not be further from the truth. More often than not, good growers tend to be exacting and uncompromising. Antony Tortul, from La Sorga, in southern France, is a case in point. Under a seemingly relaxed air, complete with bushy curls and a wide grin, this young producer runs a very tight ship, where, I suspect, very little is left to chance. He produces some 30 different wines, amounting to 50,000 bottles a year, all of which is done without any additives or artificial temperature control. He is a perfectionist, regularly examining his fermenting juices under a microscope, as well as counting and classifying his yeast populations. He is currently even conducting empirical research in his lab to understand why skin contact facilitates vinification for white wines.

“Our way of doing things couldn’t be simpler or more precise at the same time,” explains Etienne Courtois. “We make wine like the oldies did—all our presses are 100-plus years old, none are even electric. We cultivate the vines as my father learned to do and his grandfather before him, working as was done in Burgundy over a century ago. Everything is done by hand, which means we walk about 200 to 300km every year just cutting the grass between the rows.” The results are welcomed with open arms, with entire vintages selling out, and yet, perhaps counterintuitively, the Courtois are actually diminishing their hectarage. “It’s about precision,” explains Etienne. “My father used to have 15 hectares, whereas today we have about half that amount and we want to reduce it still more. You do often find that successful producers worry about not having enough wine to feed demand. They end up buying other people’s grapes to keep up. But it is like having a restaurant. If you start off with a 25-seater that is so popular you have to turn away 50 people every day, it is tempting to say ‘I’ll just open a 100-seater’ and reap the rewards. But a 100-seater is totally different. And it’s likely you become just a name on a label.”

Kevin Kelley and the canisters he used for his NPA project.

Cuvées by Antony Tortul. After corking, many are sealed with wax, as here, which is a common practice in the natural wine world.

In many senses, natural wine production obliges a grower to be far more exacting than any conventional counterpart. “I am very strict about anything that touches the grapes—pipes, pump, the lot,” says Stefano Bellotti from Piedmont’s Cascina degli Ulivi, who works sulfite-free. “Three years ago, my press broke down and I was going to have to wait a couple of days for the spare part, so a helpful neighbor suggested I use his. But when I turned up with my 10 tonnes of newly harvested grapes, I couldn’t believe my eyes. I always dismantle all my equipment after each press, and steam wash it from top to bottom so that the next day it is spotless for a new pressing. You could lick it, it’s so clean. But my neighbor is a conventional producer and adds a lot of sulfites, so he’s a lot less fussy about cleanliness. Needless to say, I couldn’t take the risk of not adding sulfites that time, as I had no idea what they had been in contact with. So long as everything is clean to start with, then I don’t worry about the rest.”

Natural wine legend Pierre Overnoy, from the Jura, France, baking bread (right), and a bottle of his Arbois Pupillin (left), which is today produced by Emmanuel Houillon.

This lack of worry is the final piece of the natural-wine-producing puzzle. So much of fermentation is actually unknown that trying to control the process necessarily loses part of its beauty (see The Vineyard: Understanding Terroir, pages 40–43). So, growers learn to let go, to trust their instincts. They trust that nature will work its magic because they have done their part to respect it in the first place. It’s a real partnership. As Austrian natural grower Eduard Tscheppe from Gut Oggau told me, “It took me six vintages to actually look forward to harvest. On my seventh, I finally knew for the first time that we would be fine. I used to be all nerves, unsure how it would play out, but now I’m in a different place and I love it.”

Natural growers don’t make wine to a formula or for a market. Instead, what they share is the pursuit of excellence, based on a love of the land and of life, in its most complete and wondrous sense. It is like walking a tightrope without a safety net. As the cellar master of one of the least known natural wine estates, and yet one of its most famous and highly regarded ever, explained to me, “C’est jamais dans la facilité qu’on obtient les grandes choses. It is only when you stand at the edge of the precipice that you have the most beautiful view. It’s here, as you risk falling into the void, that you see the extraordinary—overhead, underneath—and it’s here that greatness is possible.” (Bernard Noblet of the Domaine de la Romanée Conti).

Austrian producer Gut Oggau’s imaginative family of labels.