CHAPTER 8

“Amonster!” Martin Goodman turned on his heels, shaking his head.

Following the success of The Fantastic Four, the publisher wanted Stan Lee and Jack Kirby to create another superhero team. When Lee told him that he had a different idea, a solo book centered on what he described as an “offbeat” monster, Goodman audibly sighed and walked away. The notion of not following up on the popularity of the superhero team with another one—derivative or not—seemed ludicrous to Goodman. Lee watched his boss leave the room, dreaming of the powerful behemoth that he and Kirby had been kicking around.

“I had been wracking my brain for days, looking for a different superhero type, something never seen before,” Lee said.1 The new character had to have super strength, but not mirror the Thing or the competitor’s venerable Superman.

Mountains of fan mail had poured into Marvel’s Madison Avenue office in support of The Fantastic Four. But the insatiable fans also pleaded for a new superhero. Although he had created hundreds of comic book characters over the previous two decades, Lee agonized over a follow-up to the hit supergroup. A victim of his own success, Lee felt the pressure to keep up the momentum.

Lee pulled from classic stories and familiar narratives. Like other great artists in that era, whether Bob Dylan reimagining old folk songs into protest anthems or novelist John Updike transforming the Peter Rabbit story into a 1960s existential every-man named Rabbit Angstrom, Lee turned to his deep reading of classics. He would give fans what they wanted: an almost invincible monster as antihero. Lee created the Hulk out of traces of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Then, to add to the dramatic tension, he contextualized the comic with heavy doses of Cold War anxiety. As the world wrung its hands about the potential devastation of atomic technology, Lee made nuclear weapon testing the cataclysmic event that turns a brilliant young scientist into a rampaging behemoth. Introducing the Incredible Hulk, a brooding—somewhat terrifying—monster and convoluted antihero to the Marvel family, Lee and Kirby took another intellectual leap forward, deducing that fans would gravitate to the giant’s failures and frailties, just as they had with the Fantastic Four.

The ongoing success of The Fantastic Four—measured by mountains of fan mail, critical acclaim, and later, sales data that confirmed the heady circulation numbers—and the quick introduction of Hulk, Thor, and Iron Man, along with other heroes, set off a two-year run that changed the way people looked at comic books and their creators. Lee and Kirby became celebrities. Lee gave them monikers that readers would adopt: Jack “King” Kirby and Stan “the Man” Lee.

As a creative duo, Lee and Kirby caught a star as it shot skyward, able to bring dazzling characters to life and contextualize their stories with content drawn from what was happening in the real world around them. These heroes were different from past ones or those of the competition—they talked differently, inhabited a world that seemed authentic and right outside the window, all the while turning on fantastic plots and strong visuals.

Lee no longer had to simply kowtow to Goodman’s request to copy the super-hero team concept. But he still had to turn out new concepts to keep Goodman at bay. Under this pressure, but finally being allowed to create the kinds of comic books that he had imagined doing over the years, Lee and his artist cocreators churned out a succession of superheroes that captured the attention of rapt fans and turned others into readers for the first time. Lee now headed the hottest comic book publisher in the business, and he grew into the voice bringing those superheroes to readers around the world.

Lee felt flabbergasted when fans started writing in after The Fantastic Four debuted. Subsequently, he read the letters and put admin staff on the task of writing back. Taking the notion of using fans as a kind of focus group, Lee also asked them to write more in the pages of the comics, because he knew that he could use the insight later in developing new characters.

Many of those letters, Lee remembered, screamed “more innovative characters.” When he sat down and stared at a blank piece of paper in his typewriter, he considered these missives. He drew on what he considered the craziest idea possible, “Think of the challenge it would be to make a hero out of a monster,” he asked himself. “We would have a protagonist with superhuman strength, but he wouldn’t be all-wise, all-noble, all-infallible.”2 That monster would have elements of Frankenstein, but turn the idea on its ear by making the townspeople chasing him the real monsters, while the monster would turn heroic, though always misunderstood.

Readers picking up The Incredible Hulk #1 could get a sense of the character on the splash page. Kirby drew massive, tree-trunk arms, but also faraway, almost pleading eyes, capturing the Hulk’s pathos and internal strife. A few pages later, when brilliant but meek scientist Bruce Banner endures gamma bomb rays and transforms into the Hulk for the first time, the monster bats young Rick Jones away, demanding, “Get out of my way insect!” Via Kirby’s masterful artwork, Hulk (initially with gray skin) seems to burst from the page, charging at the reader. “Lee had come up with the perfect vehicle for exploring the notion of what it would be like to possess super powers in the real world,” one comic book historian explained. “Kirby’s chunky, monster style art” gave the hero/monster energy and also added to the existential angst and inner id that Hulk represented.3

This single panel embodies the essence of the character, as well as the achievement of its creators. Readers almost feel like they are inside the art, watching Jones’s feet lift off the ground as the monster shrugs him off. In terms of capturing the giant’s bewilderment, Lee decided to use the word “insect,” which provides immediate insight into the Hulk’s strength and feelings about “normal” human beings. He shreds the wall of the military base to escape, then demolishes a jeep that runs into him in his escape. “Have to go! Have to get away . . . to hide,” Hulk murmurs as he “storms off, into the waiting night.”

Just six months after the debut of The Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk shot out of the gate in May 1962, but struggled in subsequent months. Readers lost interest quickly, perhaps giving credence to Goodman’s criticisms. Lee couldn’t provide the comic with room to grow because the egregious distribution contract limited the number of titles Marvel could ship. When Lee grasped Spider-Man’s popularity, he had to cancel a title to make room. So, the Hulk was cut to make room for the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man in March 1963, less than a year after the rampaging hero had debuted.

The failure of the Hulk book also highlighted the incredible pressure on Lee. Goodman reviewed the sales figures and wondered what was going on with the book, always urging his editor to cancel titles that undersold. In only six issues, Lee had made wholesale changes to Hulk, so he transforms into the monster at nightfall, then later when angry; next, he kept modifying the character’s intelligence, sometimes making Hulk imbecilic and other times having him keep Banner’s super-genius capabilities. The strangest Hulk occurred in the final issue when Hulk transformed but kept Banner’s human-sized head. This version had to don a Hulk mask to keep his identity secret. When he faces off against Metal Master, he exclaims: “Don’t look so surprised, peanut! Everyone on earth isn’t a puny weakling!” Clearly, the character had gone off the rails and Lee took the revisions into absurdity.

The distribution restriction forced Lee to come up with creative methods of getting characters space, especially when fans demanded more of them, which was the case with the Hulk. In October 1964, Lee brought the green goliath back in Tales to Astonish #60, one book featuring two separate superheroes: a renewed Hulk and Giant-Man. Since early comics were anthologies containing several different stories, like the ones Lee worked on early in his career with Simon and Kirby, he kept that idea going with the team books. From the reader’s perspective, it almost seemed as if these comics were delivering more action than a solo title.

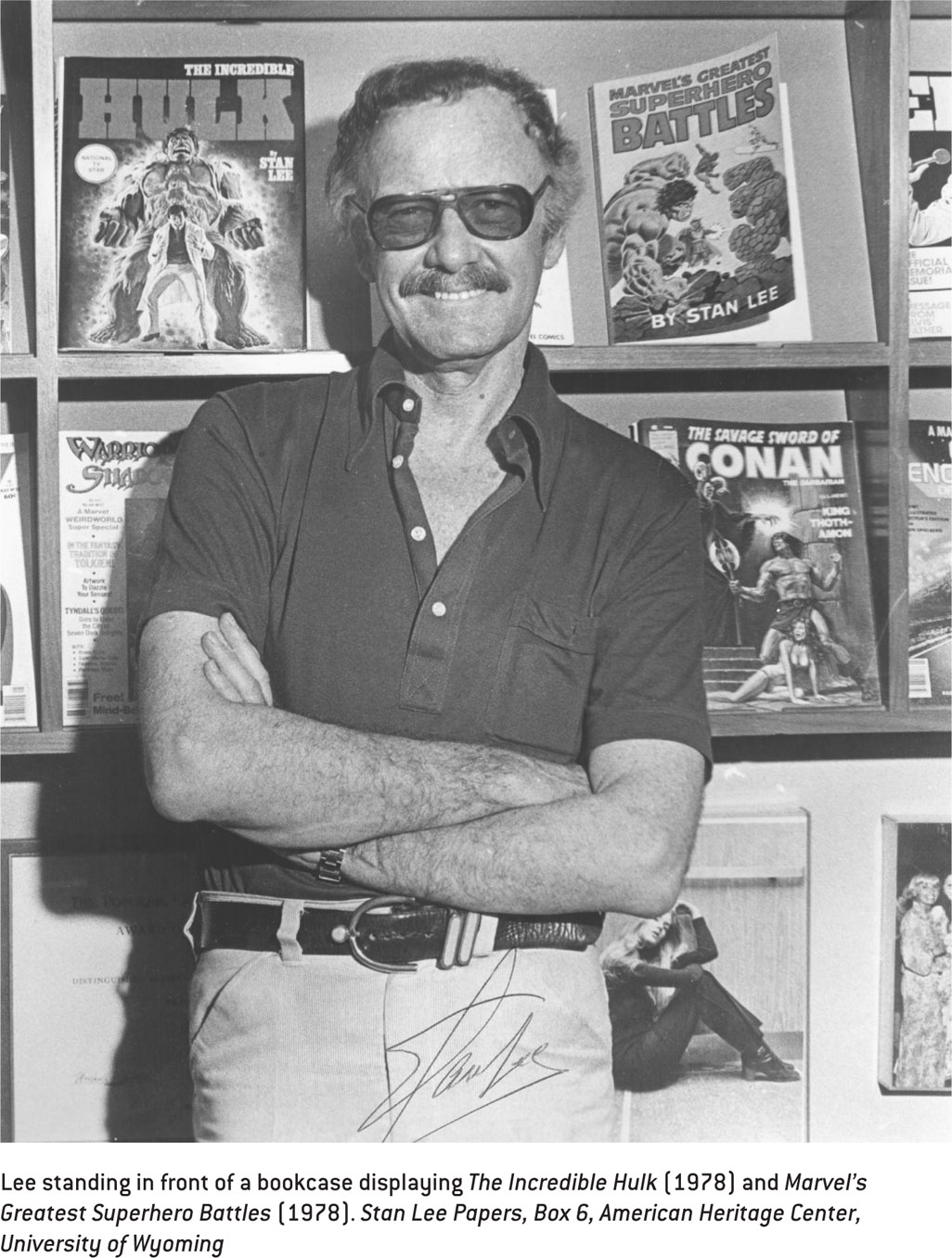

Hulk would star in the Tales to Astonish series and play a role in other titles, including Spider-Man and The Avengers. When the draconian distribution deal ended and Marvel’s popularity surged to the point that the company could launch books at Lee’s whim, he had the new Incredible Hulk #102 take over the Tales numbering in March 1968. It had taken years, but one of Marvel’s premiere superheroes would now carry on the existential mantle and grow more popular as he appeared across varying media, such as animated television, and on lunchboxes, T-shirts, and other licensed materials.

Realistic superheroes were Marvel’s strength, but dating back to the late 1930s and Superman’s tremendous impact, the industry revolved on near-invincible characters that possessed almost unimaginable powers. Lee understood that he needed a superhero “bigger, better, stronger” than his creations to date. After dozens of failed attempts, from outlandish concepts like “Super-God,” to mountains of discarded doodles and sketches in his left-handed scrawl, Lee figured, “since we were the legend makers of today, we’d simply take what had gone before, build on it, embellish it, and come up with our own version.” Instead of “God,” Lee focused on Norse mythology to create a “god” with a small “g” that would unfold the “continuing saga of good versus evil—god-wise,” just the kinds of stories that human beings had been telling for centuries.4

The Norse god that Lee and Kirby birthed would be named Thor and powered by the magical Uru hammer. The hero debuted in Journey into Mystery #83 (August 1962), which would replace The Fantastic Four in its former slot as a bimonthly book when the superhero team moved up to monthly status. The awful distribution deal that Goodman had to sign with his rival years earlier to get books on the newsstands still hampered the company. As a result, Thor and other new creations debuted in existing anthology books, rather than burst onto the scene as solo efforts. The unfavorable distribution system did, however, give Lee the opportunity to bring a new superhero along slowly and gauge fan interest prior to committing full-time resources to it.

Given the publication schedule and somewhat limited title range, Lee had to switch back and forth between the teen and western and superhero titles. In response, he searched for other writers to fill in the gaps. For Thor, he gave the scriptwriting duties to his younger brother Larry Lieber (who kept the family name). “Stan would give me a plot, usually typed,” he says. “Then he’d say, ‘Now, go home and write me a script.’” Initially, Lieber worried about his ability to write, because he “thought like an artist,” yet Stan, he claims, “did teach me” to write, providing him with insight about how to make stories positive and exciting using strong language. “Everything he said was much better than what I wrote,” Lieber explains. “I worked and I learned a lot from him.”5

Teaming his younger brother with Kirby as penciler worked well. Lee created the plots and the artist added and expanded them, because he was particularly proficient in the kind of mythic tales Thor necessitated. Soon, though, Lee took over the writing completely, in part because he liked the character and wanted Lieber to take on more western titles, which remained extremely popular, even in the super-hero age.

Writing Thor enabled Lee to draw from his study of Shakespeare, which he had read out loud as a kid. Other sources, like Edgar Allan Poe and the swashbuckling works of Alexandre Dumas, allowed him to try different dramatic voices to give the Norse god added depth. From a lifetime of watching and analyzing film, he recognized the significance of rhythm and pacing and applied it to his budding superhero writing style. He also looked to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, deciding that he epitomized the ultimate superhero, because “a superhero should be believable. There was never a more believable character than Sherlock.”6 Many of Lee’s creations were implausible, but their torment and anxiety appealed to the growing number of high school and college readers.

When Lee told Goodman about his desire to create a superhero who was also a handsome tycoon and weapons manufacturer modeled after Howard Hughes, Goodman said flatly, “You’re crazy.”7 Insane or crazy like a fox, Lee figured that Goodman hadn’t said “no” and created Tony Stark/Iron Man with artist Don Heck.

With the Cuban Missile Crisis still fresh on people’s minds, as well as former president Dwight Eisenhower’s harsh words about the growth of the military-industrial complex in his farewell address, Lee thought Stark should be the antithesis of other superheroes: wealthy, suave, and handsome, a weapons dealer seemingly without a care in the world. Lee pulled from real-world topics, which contextualized the stories, especially when creating a new character. As a result, the Hulk embodied the nation’s conflicted ideas about science and the potential negative consequences of innovation. For Iron Man, Lee would again draw on technology, but also place the hero’s origin story in a little-known nation on the other side of the world called Vietnam, long before anyone really knew anything about the Asian nation. Iron Man, the metallic alter ego of industrial titan Stark, first appeared in Tales of Suspense #39 (March 1963).

Iron Man peers out from the cover in gunmetal gray and looks stiff, more robotic than human, with no distinguishable facial features except slits for eyes and a mouth slot. Littered with Lee’s typical excitable tone, the reader is asked to speculate about “the newest, most breath-taking, most sensational super hero of all,” but also told that the character comes from the same “talented bull-pen” where the other famous Marvel superheroes “were born.” In early 1963, trust is already a defining matter for Marvel readers. Lee asks them to have faith in the new hero (and essentially Lee’s role as leader of this flock).

Stark, like many Lee characters, is a scientist but also a “glamorous playboy, constantly in the company of beautiful, adoring women.” Much of the plot (created by Lee, but written out by Lieber) is told in flashback, tracing Stark’s transition from Hughes-like industrial leader to armored superhero. A booby trap in the jungle fells Stark and his military protectors, which allows him to be captured by the enemy. Later, at the “guerrilla chief’s headquarters,” the reader learns that Stark is alive, but expected to die, because a piece of shrapnel is lodged near his heart. Wong-Chu determines that he will trick the American inventor into creating bombs until the moment he dies from the steel moving closer to his heart.

Realizing that his time is limited, Stark declares: “This I promise you . . . I shall build the most fantastic weapon of all time!” Then he begins crafting a suit designed to keep him alive and defeat Wong-Chu’s forces. With the help of Professor Yinsen, a renowned physics professor imprisoned for not helping build weaponry, Stark creates the Iron Man suit using his powerful transistor design. Yinsen fits the suit on the American just in time, and Stark stirs back to life just as the guerrilla’s forces kill Yinsen. Iron Man declares that he will avenge the professor and flies into the building’s shadows to hide until he can concoct a plan.

Confronting Wong-Chu, the superhero tosses him aside and then uses a transistor to reverse the trajectory of the soldiers’ bullets, which causes the soldiers to run. After using his “electrical power” to extricate himself from under a heavy cabinet that Wong Chu has pushed on top of him, Iron Man shoots a stream of oil at an ammo dump that the leader is trying to reach. He then lights the stream with a torch, and Wong Chu is blown up. Iron Man frees the other prisoners and walks away, covering himself in a long brown jacket and fedora. The superhero ponders his new fate as Iron Man, asking, “Who knows what destiny awaits him? Time alone will provide the answer! Time alone . . .”

The partnership between Heck and Lee in bringing Iron Man to life centered on Heck learning and adapting to Lee’s new storytelling mode, which seemed foreign for many artists who had worked at other publishers. As a matter of fact, when Heck first got a story synopsis from Lee, he balked at the process. Later, though, he grew to enjoy the creative freedom and trust that developed. “Stan would call me up and he’d give me the first couple of pages over the phone, and the last page,” Heck remembers. “I’d say, ‘What about the stuff in between?’ and he’d say, ‘Fill it in.’”8 While some artists found it difficult to adjust, Heck and many others flourished. The Marvel Method is similar to the way many television and Hollywood scriptwriters work: many smart minds tackle a script after the central idea has been established, which adds depth and nuance, even if it is birthed by one person on the team.

When Lee finally had comic books that readers were eager to buy, he created tactics for additional superhero stories to get into their impatient hands. Rather than just load up each issue with filler and old monster tales, he decided to add more superheroes to the mix in the handful of stories necessary to complete the book. For example, the Fantastic Four’s Human Torch became the primary star of short pieces that ran in the anthology Strange Tales, a leftover title from Marvel’s monster era. Lee’s intuition paid off and sales shot through the roof.

The character Steve Ditko and Lee created as a companion piece to the Human Torch grew out of Stan’s childhood listening to a radio program called Chandu, the Magician. Lee’s version became Dr. Strange, which benefited from Ditko’s psychedelic imagery and magical portrayal of the enchanted world. The story centered on Stephen Strange, an arrogant surgeon who suffers a debilitating injury to his hands, rendering him unable to operate. After hitting skid row, he journeys to visit the “Ancient One,” a mystical healer and wise man. After studying with the wizard, he becomes a supreme sorcerer and returns to set up shop on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. Unknown to the world at large, which sees him as a fraud, Dr. Strange battles the dark arts that people cannot see all around them.

Since Dr. Strange was essentially a magician, Lee had him speak in an elevated tone, rather than in the corny stage magic “hocus pocus” banter of pulling a rabbit from a hat. Lee reveled in the character and the new words Dr. Strange used. “I can lose myself completely while putting them together, trying to string them on a delicate strand of rhythm so they have a melody all their own,” he explained. “When it came to Dr. Strange I was in seventh heaven, . . . I had the chance to make up a whole language of incantations.”9 Reading the comic, one could immediately hear Lee’s cadence and voice in Strange’s interesting speech traits and in catchphrases like his frequent “by the hoary hosts of Hoggoth,” always alliterative and beguiling.

It did not take long for older teens and college students to catch on to Lee’s words and Ditko’s groovy artwork. Many tried to dissect Dr. Strange’s odd cadence and assess the literary origins. Lee barely had the heart to tell them that he made most of it up. If it was derived from anything, it was the phrases and symbols that came from Lee’s reading science fiction greats when he was growing up. When Ditko abruptly left Marvel, Lee continued writing the series, working with artists Bill Everett and Marie Severin. The mystical sorcerer attained an important place in the Marvel Universe. Dr. Strange took on villains that embodied evil itself, such as the dreaded Dormammu and the Living Tribunal. In occupying this dark realm, a case could be made that Stephen Strange was Marvel’s most powerful superhero.

The Fantastic Four surprised everyone when it became a hit, so Goodman never let go of his idea that Lee should come up with another superhero team. If one group of heroes sold well, then the natural inclination would be to add more to the roster. Plus, Goodman had reworked the deal with Marvel’s distributor, allowing them to publish more titles per month.

This deal was purely a financial decision on the part of Independent News. Independent wanted to capitalize on Marvel’s popularity, even though rival DC owned the distributor. No one thought that Goodman and Lee would actually catch up to the market leader, so the thinking was that merely allowing a few extra titles a month would just make everyone more money. Some of the men who ran Independent probably thought that they were pulling the ultimate irony over on their golf buddy Goodman: the better his comics sold, the more money it made for his bitter rival. DC execs would never have envisioned that they were essentially letting the fox into the henhouse.

Just as the fan letters had given Lee insight into the popularity of the Fantastic Four, he gathered information from mail that poured in asking him to create teams of Marvel’s heroes. Again, with DC’s Justice League of America team in mind, Lee determined that the Marvel group would consist of its most powerful characters. Since Kirby drew so many of the heroes in their other comics, Lee tapped him for The Avengers, comprised of Thor, Ant Man, Hulk, Wasp, and Iron Man. Finally, Lee had the roster of superheroes that could form a potent counterpoint to DC’s group.

Lee and Kirby combined to give the Avengers an aura of superiority, as if this supergroup were the best-of-the-best in the Marvel Universe, but also added the touches of realism that had pushed sales skyward for the other comics. Similarly to the Fantastic Four, the members of the Avengers wouldn’t always get along or agree. They too resided in New York City, in a building donated by Tony Stark. Lee called these points the “fashioning of a world for the characters to live in” and a “mood of realism to be created so that the reader feels he knows the characters, understands their problems, and cares about them.”10

When Avengers #1 (September 1963) appeared on newsstands, the action jumped off the cover—Thor’s swinging hammer, Ant-man and Wasp swooping in, and Hulk and Iron Man prepping for a fight. The reader only sees Loki, the “god of evil,” in a glimpse from behind, as if a camera has taken a snapshot over his right shoulder. The perspective makes it seem that you are there viewing the confrontation firsthand. Although Kirby’s Thor and Hulk, because of the way he drew all faces, look like cousins, the cover’s layout provides a brilliant introduction to the new superhero team.

Inside, Loki unleashes a sinister plan to draw out his brother Thor using the Hulk as bait. All the heroes respond to a distress call from Rick Jones’s Teen-Brigade after the guest-starring Fantastic Four can’t help because they are busy on a different mission. Eventually, the heroes find Hulk, who has disguised himself as Mechano, a super-strong robot performing in a traveling circus (the monster is in an odd brown jumpsuit and orange shoes and has white makeup around his mouth). Thinking that Hulk derailed a passenger train, they try to stop him. Meanwhile, Thor returns to Asgard to confront Loki. After fighting Loki and thwarting a series of traps, Thor returns Loki to Earth, revealing the plot to the other superheroes. When the god of evil turns radioactive, it seems he will fight Thor again, but Ant-Man and Wasp trap him in a lead-lined container designed for trucks to “carry radioactive wastes from atomic tests [and] dump their loads for eventual disposal in the ocean.” After stopping Thor’s evil brother, the group decides to band together, convincing the Hulk to join. Lee’s final panel announces “one of the greatest super-hero teams of all time! Powerful! Unpredictable! . . . a new dimension is added to the Marvel galaxy of stars!”

The second issue of The Avengers begins with Thor criticizing the Hulk, who threatens him in return. Here Lee is placing the supergroup directly within the realistic confines of his other characters. Thor and Hulk itch to fight one another, placing Iron Man in the mediator role. Wasp pines for Thor, whom she calls “adorable” and “handsome.” Their foe, the Space Phantom, can take the identity of others, so he replaces the Hulk and starts a fight with the others inside Stark’s mansion. Hulk gets away and is later confronted by his teen sidekick, Rick Jones, who mistakenly tells him that he can turn back to “Doctor Don Blake when you want to!” (a Lee slip-up that demonstrates the fast pace of comic book production, since Blake is Thor’s secret identity). Summoning the Norse god, the Avengers defeat the Space Phantom, but in the melee with Hulk, they reveal their suspicion of the green goliath. As a result, he quits the Avengers and leaps off into the future.

While only the second issue, Lee has already changed the team (also adding Giant-Man) significantly and presented Hulk as a nearly indestructible force. Over the next several issues, the group will battle Hulk when he teams up with Sub-Mariner. Later, the Avengers find Captain America and bring him into the fold. In a call-out box, Lee trumpeted the return of the red, white, and blue super soldier, telling the reader that Kirby had drawn the original and that his first story was a Cap tale: “Thus, the chronicle of comicdom turns full circle, reaching a new pinnacle of greatness!” Lee also urged fans to “save this issue,” more or less pushing the notion that comic books could be collector’s items, explaining, “We feel you will treasure it in time to come!”

The Lee/Kirby creative team set 1963 ablaze with quirky superheroes who seemed quite a bit like real people who happened to stumble into their tremendous powers and had to deal with the ramifications. Fearing that readers might get tired of these accidental heroes, Lee broke the mold and thought up a team of individuals who were born with “unique abilities.” This team, he recalled, would be “mutants . . . an aberration of nature.” Together, Lee and Kirby created two groups—one good and one evil—which Lee thought had “an air of freshness and surprise.”11 He stumbled on the word “extra,” as in the extra powers the characters possess, after Goodman shot down his original title: “The Mutants” for being above the heads of young readers. The publisher agreed to “X-Men” (as if that made more sense), so Kirby and Lee sat down to brainstorm, plot, and plan.

The world that Lee and Kirby created centered on the idea that human beings continued to evolve and some people were born with special powers that came to light when the person hit puberty. They reasoned that teenagers with amazing powers would delight young fans. Such mutants, like Cyclops, who shot laser beams from his eyes, and Jean Grey, who had telekinetic powers that enabled her to move objects at will, attended Professor Charles Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters. There they learned to harness their abilities and build on them for the good of humankind.

The X-Men series enabled Lee to explore the alienated feelings that many teens experienced, while also providing the group with kinship via their relationship with Professor Xavier, who provided a father figure for them. The school turned into an extended family for the youths, many of whom had faced discrimination for having abilities that “regular” humans did not understand. Their powers were a blessing and a curse. Only the wise counsel of Professor X and their experiences battling evil as a team could provide them with a semblance of normality, which always seemed fleeting.

Running from 1963 to 1970, X-Men never really generated strong sales, despite the high hopes Lee had for it. He and Kirby faced tremendous pressure to work on the comics that did sell, so when the artist asked for a replacement, Lee granted his request. Later, the writer moved himself off the book to concentrate on better-selling titles.

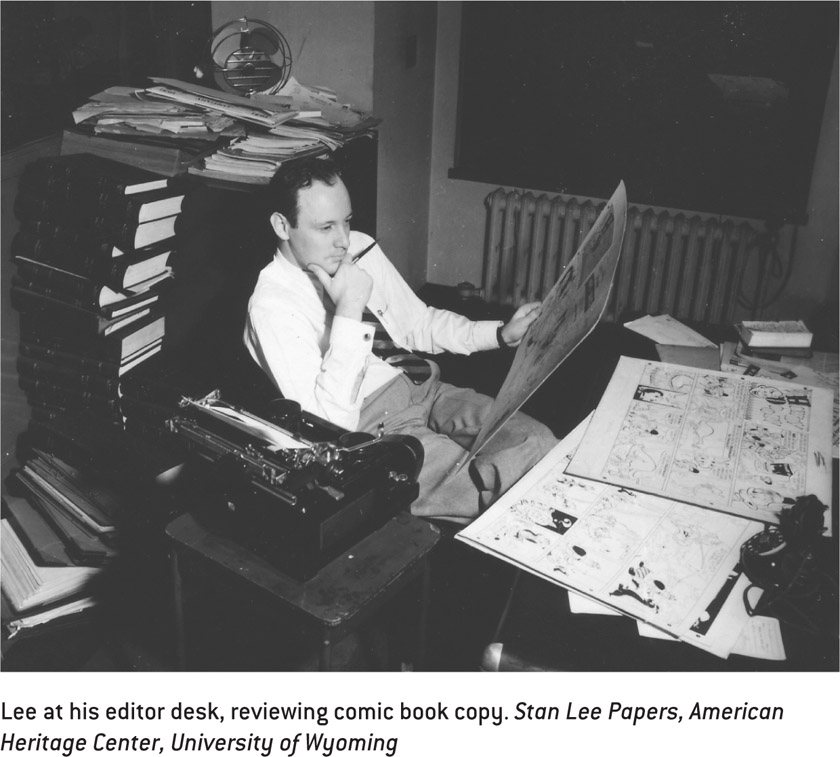

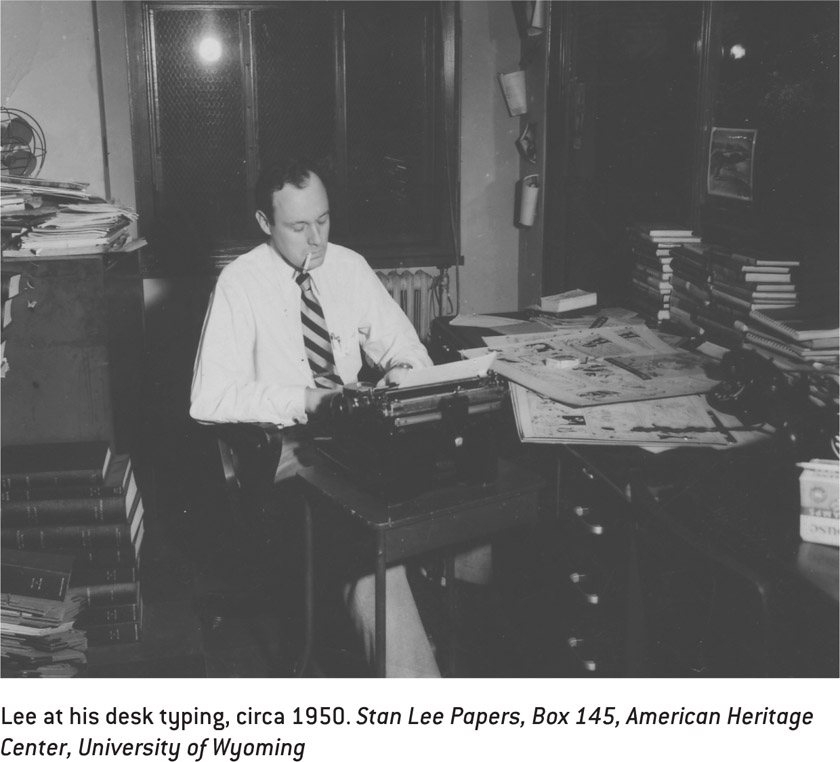

Once the superhero business took off, Lee created a system that centralized his control over nearly every aspect of the creative side of the comic books division. Some of these work responsibilities were the continuation of what he had been doing in art, editorial direction, and general management, but other aspects grew out of necessity, since Marvel changed as it became more popular. Lee may not have been trained to be a manager or talent scout, but his years in the business honed these skills.

Lee not only knew when to move an artist onto a different piece of work, like the critical decision to replace Kirby with Ditko on the early Spider-Man efforts, but he also respected the freelance artists who served as the backbone of the comic book world. He recognized talent and assembled a crew of artists to infuse Marvel with a new spirit. The superhero comics married the art and writing in a way that the business hadn’t seen before. Strong freelance artists served as visual partners for the snappy dialogue and personality traits that he and other writers used to differentiate the company.

Lee’s unique ability was to mirror the voice and style of the early 1960s and bring it into comic books. As a result, Marvel readers get the humor and satire that actor Peter Sellers brought to The Pink Panther (1963) and Dr. Strangelove (1964) while also appreciating the full-throttle heroic characters, like Ian Fleming’s James Bond, whose action-packed films like Goldfinger (1964) encompassed a mix of sophistication, violence, and superhero-like deeds. Popular culture was changing. Lee found a groove with realistic superheroes who balanced great power with existential angst, an idea surging through mainstream media. He explained:

We try to write them well, we try to draw them well; we try to make them as sophisticated as a comic book can be. . . . The whole philosophy behind it is to treat them as fairy tales for grown ups and do the kind of stories that we ourselves would want to read.12

As editor and art director, Lee guided the voice and style of the company by working with artists and writers he trusted. When he found a person who possessed first-rate abilities, Lee deliberately indoctrinated the artist or writer into the company’s distinctive process. For example, Lee quickly realized the beauty in the artwork of George Tuska, a stylist who some insiders felt had the most unique ability in all of comic books. It did not take long for Tuska to become one of Lee’s favorites. According to Daredevil artist Gene Colan, “Stan always would hold [Tuska’s] work up as the criteria of how he wanted the other artists to draw.” This kind of management style enabled Marvel to be distinctive, yet also gave his artists a template that emphasized the kind of work he needed done, and completed quickly.13

In a business that could often be cold and ruthless, Lee cultivated talent. He had to do so, since Marvel lagged well behind DC Comics, its rival perched at the top. He needed talented freelancers for his vision of producing quality comic books that people would hold to a higher standard to work, so Lee took chances on young artists and writers.

At the start of his career, for example, Colan could not get into DC, which had locked down its talent and locked out others who wanted in. For the venerable industry leader, he simply did not have enough experience. Colan recalls, “Stan could see something in my work that no one else could see. . . . That’s what really got me started, Stan’s faith in my ability. Although it wasn’t completely there at the time, I was too young and had a lot to learn.”14 The other harsh reality staring Lee in the face was the relentless publishing schedule that placed a real premium on not just speed, but efficient speed.

For artists who expected to get committed to a specific script (or were used to that treatment at other comics and magazine firms), Lee’s style changed their outlook. Colan remembered Lee giving the artists “such unprecedented freedom,” which translated to happier artists. “I’d talk with Stan about a plot over the phone, and I’d tape record his whole idea—it’d just be a few sentences.” Lee would tell him: “This is what I want in the beginning, the middle, and what I want in the end . . . the rest is up to you.” For Colan and the other trusted freelancers, this set a precedent. “I had all the characters work for me, what they looked like was up to me—except those that were already established. But whatever I did, I could do.”15

Despite his growing public persona that turned him into the face of comic books for the general public, the day-to-day Lee understood the volatility of the market and its consequences. As a result, many artists grew into big Lee supporters. The camaraderie that developed had important ramifications: they worked long hours to meet the company’s needs, but Lee rewarded them by keeping steady work coming their way. Colan, for example, spoke about the grueling hours necessary to produce two complete pages a day, which then translated to about two full books per month. Maintaining this schedule took much longer than forty hours per week. The artistic freedom represented by the Lee method, then, balanced the physical necessities.

The core group of freelance writers Lee took under his wing received a master class in comic book writing. Dennis O’Neil, a former journalist who started his comic book career as a staff writer at Marvel and later became widely known for his work on Daredevil, Batman, and Green Lantern, explains, “That first year working for Marvel, my job was to, in effect, imitate Stan.” For the young writer and his colleagues, the message was clear and direct: “Stan’s style really was Marvel.”16

For O’Neil, Roy Thomas, and the other writers, Lee served as a commanding general, but with a level of benevolence that most driven leaders do not possess. He didn’t spend a lot of free time mingling with his staff—primarily based on age difference—but their admiration ran deep because they really were the first of Lee’s “true believers.” O’Neil says, “I learned the basics. I learned the basics by imitating Stan, and he was, by a huge margin, the best guy to imitate back then.” For O’Neil, they did revolutionary work and under the guidance and training of the industry’s pioneer: “The best comic book writer in the world.”17

Lee’s eye for talent, though, is clear, seeing what the writers and artists he commissioned would later go on to do in the business. In the years that Marvel began its ascent on the backs of the characters Lee, Kirby, Ditko and others created, the company served as a kind of comic book university, teaching the next generation how to build and expand what would become famous as the “Marvel Method.” The new style of creating a comic book actually grew out of Lee’s determination to keep freelance artists working. If they had to wait around while he finished writing a script, they were essentially losing money.

Marvel’s success with superheroes upped the pressure on everyone in the creative process to perform at a faster rate, even Lee, who neared the limits of how quickly a person could write. He famously hired three secretaries and would dictate stories to them in order, running through one as the other two typed out the notes.

“In the beginning, I was writing almost all of the stories for Marvel. I couldn’t keep up,” Lee said. Comic book production demanded that all the various creators be kept busy at all times. For the freelance artists the need was much more basic: if you aren’t drawing pages, you aren’t getting paid. Lee developed a way to keep them active. He remembers that they would pace around after they dropped off their work, always wanting more. Too often Lee simply had no way to keep up with the demand, so he changed the system: “I couldn’t stop what I was doing . . . [instead] I would tell him generally what I wanted. He would go home and draw it any way he wanted, bring the illustrations back to me, and then I would put in the dialogue and the captions.”18

Without really planning a new system for creating comic books, Lee came up with the Marvel Method or, as he explained, it “happened purely through need.” The process played on the strengths of Lee’s freelance artists. He recalled: “These guys thought like movie directors. They were really visual storytellers.” As a result, Lee could give them lots of latitude to interpret what he wanted from a quick story conference or brief phone discussion. “When I would give them a plot, they knew how to break it down—how to begin it, how to end it, where to put the interesting parts.” When the artists missed the mark, Lee discovered that he could amplify the artwork with sound effects or extra dialogue. “It started as an emergency measure—it’s the only way to keep these guys busy—but I realized that you get better stories that way.”19

The unimaginable successes Marvel experienced in the early 1960s took place as Lee and Kirby cemented their creative bond. It put Marvel’s future directly on their shoulders. The most logical and straightforward aspect of their relationship centered on mutual respect. Later, it grew convoluted. There were inherent difficulties, certainly, even as they worked on the characters that would serve as the foundation of the Marvel cosmos. In the 1960s, Kirby worked for and reported to Lee, even though he had been Lee’s boss when the writer/editor started as a teenage office boy. Though their roles were reversed, the truth was they were dependent on one another.

Perhaps even more pointedly, neither realized the immense frustration each secretly held. They both detested many facets of the comic book industry and its seemingly continuous boom-and-bust financial cycles. Lee and Kirby were friends and had a long professional history, but their friendship did not carry over to the point where they would share intimate details about their hopes and dreams. If either had actually opened up to the other in this fashion, it might not have changed the way their relationship unfolded, but it might have enabled them to see that they had more in common than they ever believed.

Clearly they needed each other as professionals. After decades of keeping the comic book division of Goodman’s empire alive, Lee recognized talent and knew Kirby was one of the best pencilers in comics. As editorial and art director, he decided that Kirby’s style would serve as the company’s signature style, just as his own writing became the de facto voice. Artist Gil Kane, who worked for Marvel on and off for decades, most memorably drawing many of their covers in the 1970s, recalled:

Jack’s point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field. . . . They would get artists, regardless of whether they had done romance or anything else and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby. . . . Jack was like Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That’s what was told to me, that’s what I had to do. It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.20

The entire Marvel line revolved around the Kirby style. For example, Jim Steranko passed the Marvel employment test by inking two of Kirby’s penciled pages for S.H.I.E.L.D. He then worked with Kirby on three Nick Fury issues as a kind of apprenticeship. According to writer Chris Gavaler, “Becoming the Marvel house style seems to have required Kirby to regularize his layouts, presumably so they could be more easily imitated. Variation and innovation are not qualities easily taught, and they do not produce a unified style across titles.”21 Yet, Steranko built his later reputation on irregular page layouts, which introduced art deco, postmodernism, and new-wave impulses into Marvel’s pages.

All DC could do, despite its own iconic superheroes, was try to keep pace with Marvel. By the time DC recovered—sort of—by producing its own colorful, exciting covers, the leap Marvel had taken created the foundation for Goodman’s firm to eventually take over the top spot in the comic book business. In the battle between Marvel and DC, fans were voting with their nickels, dimes, and quarters.

As a result, an innovative, colorful, and exciting character like Metamorpho, created by DC mainstays George Kashdan and Bob Haney in late 1964, seemed like a Marvel clone rather than a new superhero. But there was reason to think that DC simply attempted to mimic Marvel. The Metamorpho cover (The Brave and the Bold #57) mirrored the kind of language that Lee popularized, exclaiming: “See the amazing powers of the world’s most fantastic new hero.” The book also used dynamic imagery and colors, yet Marvel had already created a beachhead in the war over the comics fans would determine to be “hot.” It took some time for the upstart to displace the market leader, but few doubted the excitement that Lee and Kirby created down on Madison Avenue. Once Marvel had a couple hit titles on the books, Lee wanted to add to its roster to keep the forward progress. “I was like a crapshooter rolling one great pass after another,” Lee said. “You just don’t stop when you’re on a winning streak.”22

In the back of his mind, Lee believed that the superhero boom would eventually crash, just like all the other cycles he had experienced. As a result, he moved fast to generate new titles and new characters to capitalize on the trend. He kept his freelancers hopping, driven by his own seemingly endless supply of optimism and energy. Under relentless publishing deadlines, Lee had to live and breathe the constant balance of creativity and commerce, artwork versus commodity. Under his leadership, Marvel would spend the rest of the decade solidifying its universe.