In 479 BC, immediately after the victories of Hellas (the ideal, never actually achieved, of a united nation of all the Greeks) over the Persians at Plataea and Mycale, the Athenians persuaded those who had fought at Mycale to bring the liberated Greeks of Ionia into the Hellenic Alliance for their long-term protection. This was against the wishes of the Spartans, who had argued that they should be repatriated from Asia. The Hellenic fleet then sailed to the Hellespont to destroy Xerxes’ bridges of boats, which had actually already been dismantled in 480 BC. Considering their mission accomplished, the Peloponnesian contingent went home. However, the Athenians, led by Xanthippus, the father of Pericles, stayed on and captured Sestos, establishing it as one of their most important overseas naval bases.

Immediately after the battle of Plataea and the surrender of Thebes, the Athenians had set about rebuilding their city and its walls against the strongly expressed wishes of the Spartans, who were nervous of Athens’ recently acquired strength, so powerfully demonstrated in the war against the Persians. According to Thucydides, ‘the Spartans did not make any show of anger with the Athenians … but were privately angered at failing to achieve their purpose.’

In 478 BC, Pausanias, the Spartan regent who had led the Greeks to victory at Plataea, took a Hellenic fleet to Cyprus, conquered most of the island and then sailed north and took the city of Byzantium from the Persians, gaining control of the Bosporus. However, at this point, the rest of the Greeks rejected Spartan leadership on the grounds that Pausanias was now ‘acting more like a tyrant than a general’ (Thucydides I.95: all subsequent Thucydides references are given with book and paragraph numbers only). They placed themselves under the Athenians, who almost immediately started to raise contributions from allies to support the collective effort of defending Hellas from Persia. These funds were to be administered by Athens but held on the sacred island of Delos, and the voluntary alliance known as the Delian League had come into being. In not much more than a year the first roots were put down of the conflict that would, from 459 BC, so violently split Hellas for most of the rest of the century.

The League was successful in its purpose of protecting Hellas from Persia. By the time of its great victory on the Eurymedon River on the north shore of the eastern Mediterranean in 466 BC, it controlled the whole of the eastern Aegean and the western coastal strip of Asia. Sparta played no part in the Eurymedon campaign. A year or so later the important island of Thasos seceded and it was to take an Athenian expeditionary force two years to bring about its return to the League. The Thasians appealed to the Spartans for support, which suggests there was some expectation that it might be given.

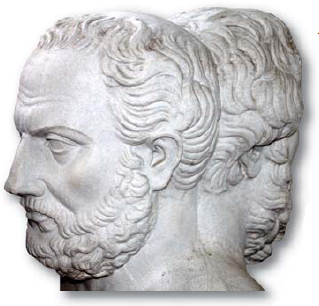

Portrait of Thucydides (c.455–395 BC) back-to-back with Herodotus (c.485–425 BC) in a Roman copy of a Greek double bust. Herodotus’ account of the Persian War stands as a massive evolutionary stepping stone between the archaic oral tradition of narrative of the past and the recognizably ‘modern’ history-writing of Thucydides. Thucydides’ superb account of the Peloponnesian War is regarded as a foundational text in Western political thought. It is also an excellent source for the military historian because Thucydides lived through this war and served Athens, at least competently, as a general in it. He deals with the Pylos campaign in the first third of Book IV of the eight books of his unfinished history, which takes the conflict to 411 BC, seven years before Sparta’s final victory. Sicily 415–413 BC is the only campaign covered at greater length. Naples Museum.

However, that year Sparta was struck by a massive earthquake, which killed tens of thousands and flattened most of their buildings, and also by a rebellion of their Helot subjects in Messenia, their third since the Spartans conquered them in the 7th century BC. By 462 BC the Spartans had the Messenians contained in Ithome, their mountain stronghold, but were making no further progress. They had little expertise in siege warfare, most probably because they had no taste for it.

They called on the Athenians, still formally their allies, for help and they sent a large force under Cimon. He was son of Miltiades, the victor of Marathon, and had led the Greeks to victory at Eurymedon. But, in Thucycidides’ words, ‘the first open difference between the Spartans and the Athenians came about because of this campaign’. The siege dragged on. The Spartans became increasingly nervous that the Athenians, with their more liberal attitudes, might become dangerously sympathetic with the enemy, so they told them they were no longer needed. The Athenians took offence, breaking off the alliance that had been formally in place since the Persian invasion and entered new ones with Sparta’s old enemy, Argos, and with Thessaly, threatening Sparta’s friends in Boeotia. Finally, they began work on the long walls that would connect the city securely with Piraeus and the sea. The roots of conflict had spread wider and deeper.

In 459 BC the Athenians made a landing on the Peloponnese at Halieis. It is not known if this was intended as an act of war or if the purpose was simply to beach for the night and obtain food and water by reasonably peaceable means, but a force from Corinth confronted the Athenians and defeated them. Their ship-borne hoplites were probably outnumbered and the much larger throng of light-armed rowers and seamen who also landed would have been quite easily overwhelmed. Immediately after this the Athenian fleet defeated a Peloponnesian fleet off the island of Cecryphalia west of Aegina. These were the opening clashes in the 13 years of conflict known as the First Peloponnesian War, and immediately fitted the general strategic pattern of Peloponnesian superiority on land and Athenian superiority at sea.

Then the Athenians went to war with Aegina, an enemy in the past and historically aligned with the Peloponnese, to force the island into the Delian League. Around this time Megara voluntarily joined the League, pulling out of the Peloponnesian Alliance because of border disputes with Corinth. This city was strategically placed on the main route between the Peloponnese and Attica and Boeotia, and controlled the ports of Pegae on the Corinthian Gulf and Nisaea on the Saronic Gulf.

Greece was still at war with Persia and the Athenians had diverted a large force from operations against Persian interests in Cyprus to support a revolt against Persian rule in Egypt. Artaxerxes, the Great King, tried without success to use Persian gold to persuade the Spartans to invade Attica to make the Athenians withdraw from Egypt. The Corinthians saw the Athenians’ heavy commitment on two fronts, Aegina and Egypt, as an opportunity to take Megara back. However, the Athenians mobilized their reserves, ‘the old and the young’ above and below campaigning age, marched the 50km into the Megarid and fought the Corinthians to a draw in a closely contested battle. Both sides claimed victory but a second battle a few days later ended decisively in the Athenians’ favour.

No details of the fighting survive except for Thucydides’ brief description of an incident during the Corinthian retreat. A large element lost its way and became trapped in a piece of land surrounded by a deep ditch. Athenian hoplites blocked the entrance and their light-armed troops, psiloi, surrounded the Corinthians and pelted them with stones ‘causing them great loss’ (I.106). The two battles outside Megara may have been predominantly between massed hoplites, but less conventional engagements similar to that described here were to become much more the norm.

In 457 BC Phocis invaded neighbouring Doris. Honouring ancient ties with the Dorians, the Spartans sent 11,500 hoplites, 1,500 Spartans and 10,000 allies, to their aid and ejected the Phocians. Then the Spartans received information that the Athenians were planning to block their return to the Peloponnese. They delayed in friendly Boeotia, positioning themselves to exploit the outcome of a conspiracy to overturn democracy in Athens that they knew of. The Athenians marched against them with all 14,000 of their hoplites of fighting age, 1,000 from Argos and other allied contingents.

At Tanagra the two leading powers of Hellas faced each other in battle for the first time. The Spartans and their allies won a bloody victory and returned home unopposed. The conspiracy in Athens came to nothing and, two months later, with characteristic resilience, the Athenians returned and defeated the Boeotians at Oenophyta, not far from Tanagra. This victory gave them control of Boeotia and Phocis, and at about this time, Aegina surrendered. Also, an Athenian fleet sailed round the Peloponnese and raided and burned Sparta’s naval base at Gythion. It went on to capture the seaport of Chalkis, a Corinthian possession at the west end of the Corinthian Gulf, and mounted a successful attack on Sicyon, a neighbour of Corinth at the east end.

Themistocles (c.524–459 BC): his leadership at Salamis and strategic vision of Athens as dominant naval power in the Aegean saved Hellas from Persia. After the war he supervised the refortification of the city and took charge of negotiations with the Spartans, playing for time until this was completed. In 478 BC the Athenians went on to fortify the port of Piraeus under his direction, ‘laying the foundations of empire’. Ostia Museum, Rome.

At this time, the Athenians took possession of Naupactus, a seaport that commanded the narrowest point at the west end of the Corinthian Gulf. The Messenians in Ithome had finally surrendered in 456 BC and the terms agreed allowed the defenders to go into exile outside the Peloponnese. In another act of hostility to the Spartans, the Athenians settled them in Naupactus; both the city and its new inhabitants were to prove valuable assets in the years ahead. The only bad news was the failure in 454 BC of the intervention in Egypt and the total loss of the expeditionary force.

The heavy hoplite spear, doru, and shield were lethally effective in combat with the more lightly armed Asian troops, especially in Spartan hands. They were the offensive and defensive armament that continued to define the hoplite through the second half of the 5th century BC when body armour and closed helmets were no longer standard equipment. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In that year the Athenians moved the treasury of the Delian League to Athens, arguing that after this setback it would be safer from the Persians there. League members now began to be referred to officially as the cities that Athens ruled and were often treated as such. The Spartans’ concern at the growth of Athens’ power had been well justified. Thucydides explains why they did so little about it. ‘The Spartans could see this but did not attempt to hinder it except in minor ways and remained inactive for most of the time. Historically they had been slow to go to war except when it was absolutely necessary and, in any case, they were constrained by conflict close to home.’ (I.118) The disastrous effects of the great earthquake of 464 BC must also have been a significant factor.

Around 454 BC the Athenians tried unsuccessfully to extend their influence into Thessaly. They also carried out operations at the eastern end of the Corinthian Gulf, using Pegae, Megara’s western port, as their base; Pericles, now a force in Athenian government and a driver of the city’s expansionist policies, was in command. They won a battle against the Sicyonians and brought Achaea over to their side. However an uneasy truce was agreed between the Athenians and the Peloponnesians and hostilities were resumed with the Persian Empire in Cyprus and Egypt. These seem to have come to an end by 450 BC.

There is uncertainty as to whether a formal treaty with Persia (the so-called Peace of Callias) was actually agreed, but it was no longer easy to justify the Delian League as the defensive alliance originally formed. In 447 BC Boeotians who had been sent into exile after the Athenian victory at Oenophyta ten years before had returned and regained power in some of the cities. They defeated an Athenian force sent to remove them at Coronea and negotiated independence in exchange for the hoplites they had taken prisoner.

Then, in 446 BC Euboea rebelled against Athens. Pericles took an Athenian army over and, while there, heard that Megara had decided to realign with the Peloponnesians and that a Peloponnesian army was about to invade Attica. Somehow this crisis was defused. Thucydides deals with it in a few, matter-of-fact words: ‘Pericles quickly brought the army back from Euboea. The Peloponnesians under Pleistoanax, the Spartan king, invaded Attica as far as Eleusis and Thria, destroyed the crops and advanced no further and then marched home. The Athenians then went back over to Euboea under Pericles’ command and subdued the whole island.’ (I.114). Plutarch in his Life of Pericles expands on this a little:

He did not venture to join battle with hoplites who were so many, so brave, and so eager to fight. But, he saw that Pleistoanax was very young, and that out of all his advisers he depended most on Cleandridas, whom the ephors [senior elected magistrates] had sent along to be a guardian and an assistant to him because of his youth. He secretly tested this man’s integrity, speedily corrupting him with bribes, and persuaded him to lead the Peloponnesians back out of Attica. (Plutarch Pericles 22)

The Hellenic Navy’s Olympias, a full-size, fully functioning reconstruction of the elegant and agile warship used by both sides in the Peloponnesian War. Doru was used as a poetic term for the trireme and, as a weapon in the hands of the Greeks, especially the Athenians, it played as important a part in the victory over the Persians as the hoplite spear. Masts were unstepped for battle because the trireme was much more manoeuvrable under oar power. All sailing gear was generally left on shore to reduce weight. Photograph Hellenic Navy.

Avoidance of a full hoplite confrontation with the Spartans and their allies was actually a major strategic priority for Pericles, because he knew the Athenians and their allies would be the losers. However, the terms of the peace treaty that was then agreed to run for 30 years suggest that no individual needed bribing. The Athenians were to give up all the places they held in the Peloponnese, and also Nisaea and Pegae in the Megarid. So, without striking a blow, the Peloponnese had been secured. But, on the other hand, the treaty placed no restriction on Athenian activities throughout the rest of the Greek world. In 447 BC work began on the construction of the Parthenon and the rest of the great public building programme which continued through the 430s BC. This was financed by what could now only be described as imperial tribute from many cities and states that had formerly been allies in the Delian League.

The rest of the decade was peaceful, and during this time Athens grew in power and wealth. However, in 440 BC Samos went to war with Miletus and the Athenians intervened at Miletus’ request. They imposed democracy on Samos as part of their resolution of the conflict, but after they had returned home, Samian exiles, with Persian support, overturned the new government and declared independence. Athens reacted quickly and laid siege to Samos: after nine months, the Samians surrendered. At about the same time Byzantium rebelled but was not allowed independence for long. Three years later, in another demonstration of imperial power and ambition, Athens colonised the strategically and economically important Thracian city of Amphipolis.

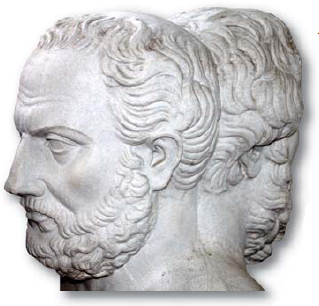

Sometimes labelled as a portrait of Leonidas, this imposing hero-figure was probably part of a group decorating a temple pediment. It was sculpted earlier in the 5th century BC than the battle of Thermopylae and at a time when portraits were not made of living individuals. However the serene and unflinchingly resolute expression is an excellent reflection of the unique Spartan military spirit. Sparta Museum.

In 435 BC Corcyra, a significant naval power and an important staging post for trade with Italy, Sicily and the west coast of northern Greece, went to war with Corinth over the seaport city of Epidamnus, a colony on the coast of Illyria which historically they shared. Corcyra won a decisive victory over the Corinthian fleet but, after a year of intensive shipbuilding, the Corinthians launched a new campaign. Corcyra, not aligned with either Athens or Sparta, now needed support and persuaded Athens to agree to an alliance. It was to be a defensive alliance out of public respect for the Thirty Years Peace.

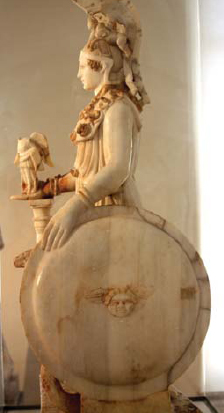

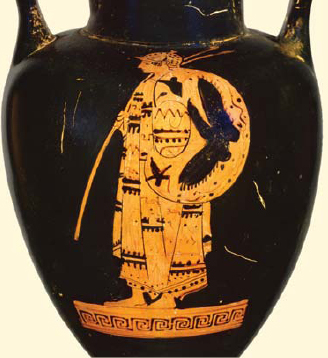

Athena, the complex patron goddess of Athens, equally and appropriately associated with military prowess and the more civilized qualities of craft skill and wisdom. This statuette is a miniature, 3rd-century copy in marble of the massive figure made by Phidias and erected in the Parthenon on its completion and dedication in 438 BC. It was faced with ivory and gold; the gold was stripped off in the 420s BC to help fund the Athenian war effort. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

But by now fresh conflict seemed inevitable and it made sense to keep the substantial Corcyrean navy out of the hands of the Peloponnesians. Ten Athenian triremes joined a 110-strong Corcyrean fleet facing 149 Corinthians and allies between Sybota on the mainland and the southern tip of Corcyra. At first they stood off, but when the Corinthians began to get the upper hand, they became fully involved. Their intervention did not prevent the Corinthians routing the Corcyreans, inflicting heavy losses and driving them back to shore. But the Corinthians then withdrew in the face of Athenian reinforcements and were unable to exploit their crushing victory.

This was the first clear breach of the treaty between the Athenians and the Peloponnesians, but war was not yet formally declared. Then in 432 BC, Potidaea, a commercially and strategically important seaport in Chalcidice, broke away from Athenian rule, provoked by an increase in tribute and by measures to cut off their historic links with Corinth. This threatened to destabilize the whole region. Both Athens and Corinth sent fleets and strong hoplite forces and, after winning a battle nearby, the Athenians laid siege to the city. In the diplomatic exchanges that followed Sparta demanded that the siege of Potidaea be abandoned. Closer to home, they stipulated that Aegina be granted independence and that crippling trade sanctions, recently imposed by Athens on Megara, be removed. A final embassy delivered a laconic, overarching message. ‘The Spartans want peace to continue. It will if you grant the Hellenes independence.’ (I.139) In the Athenian Assembly Pericles spoke powerfully and decisively in favour of rejecting all Sparta’s demands, arguing that war was both necessary and inevitable, and that Athens’ naval expertise and power, financial and manpower resources, and extensive possessions would guarantee ultimate victory. His only concession was that Athens would not start the fighting.

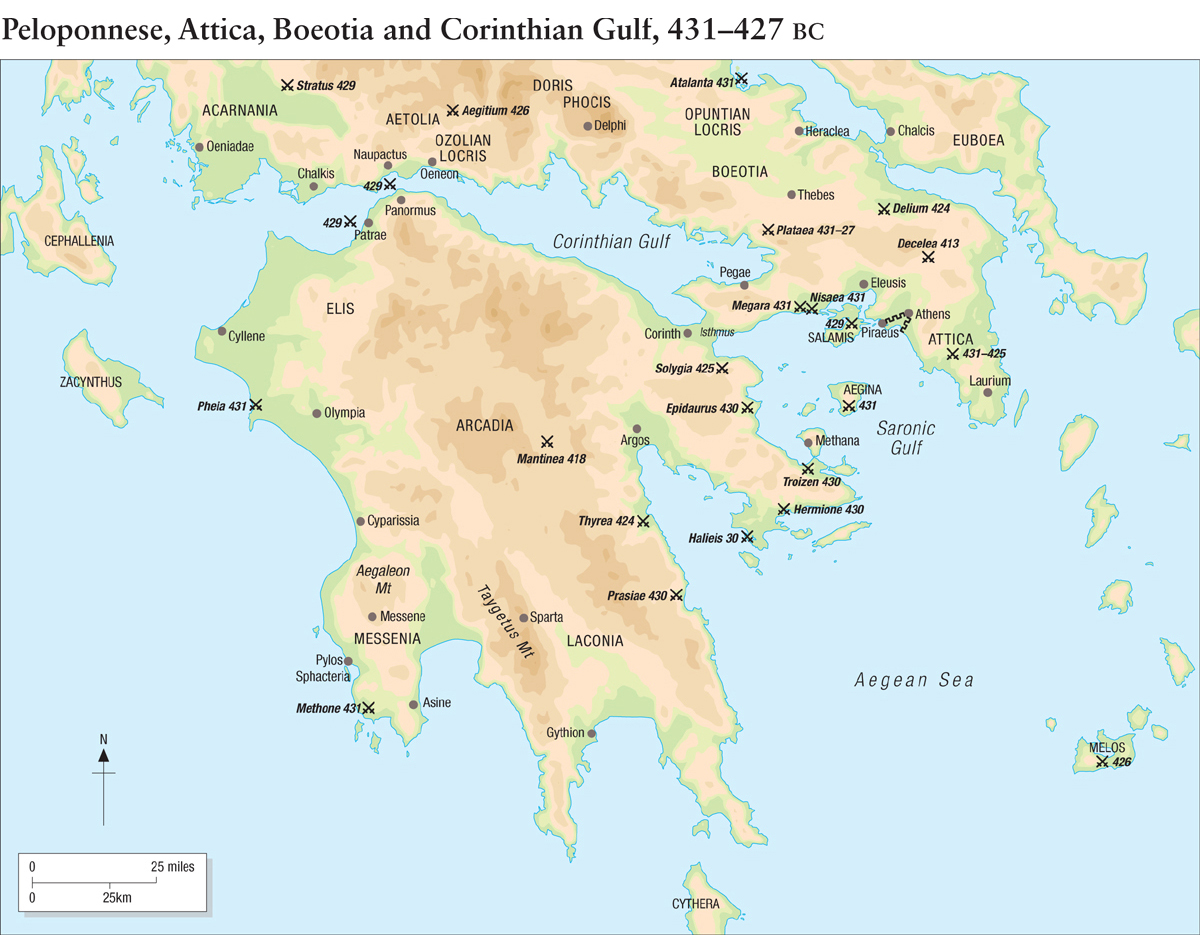

Early in the summer of 431 BC, Thebes, Sparta’s most powerful Boeotian ally, attempted a surprise attack on their neighbour Plataea, a staunch ally of Athens in the Persian War. Although more parochial an affair than Sybota and Potidaea, it finally triggered open preparations for war between the two power blocs. Athens sent a small force to strengthen the garrison and assisted in the evacuation of non-combatants in preparation for the siege that was to follow, which lasted for four years.

Archidamus, the Spartan king after whom this decade of war is named, led a massive Peloponnesian army into Attica and the population took shelter behind the walls of Athens. The corn was now ripe and Archidamus’ troops lived off the land and wrecked the crops in time-honoured fashion. The invasion was intended to provoke a full-scale battle to bring the war to a quick and decisive end. However, the Athenians could bring in ample food supplies by sea and their direct response was limited to cavalry sorties. These served to contain the invading force to some extent, and supported morale inside the walls by protecting the land closest to them.

At the same time a large fleet of more than 150 triremes was sent to cruise round the Peloponnese. It raided a number of coastal strongholds and settlements, including Methone in the south-west, and had an uncomfortable encounter with Brasidas, one of the war’s most capable commanders, making his first appearance in Thucydides’ history (II.25). Sailing up to the northwest coast the fleet linked up with Messenians from Naupactus to occupy Pheia for a period. Later in the summer they carried out successful operations against Corinthian interests in Acarnania and also brought the island of Cephallenia into the empire.

Soon after this fleet had sailed, Archidamus, with provisions now in short supply, marched his army home across the Isthmus taking it north and west through Boeotia before turning south. This was not to keep it out of reach of the Athenians but because Attica and the plain of Eleusis had already been stripped of food.

A smaller Athenian fleet was sent to patrol the west coast of Euboea and attack places in Opuntian Locris, Boeotia’s coastal neighbour. It also established a fortified outpost on the island of Atalanta to police these waters and serve as a base for harassing operations on the mainland.

Additional naval force was used to neutralize Aegina as a threat in the centre of the Saronic Gulf. Its entire population was uprooted and replaced with colonists from Athens. The refugees were given asylum by Sparta and most of them settled in Thyrea on the east coast of the Peloponnese, which the Athenians took and burned eight years later. Finally, towards the end of the summer, Pericles led a large force into the Megarid. This was to become almost an annual event, like the Spartan invasions of Attica.

The first year of the war had gone well for Athens. It is unlikely that the invading army had done any lasting damage to the relatively small area of Attica’s extensive farmland it had laid waste, and Archidamus had little to show for his massive expenditure of resources. Any shortfall in food supplies in Athens had been easily covered from overseas and the Athenian fleet had carried out its missions without any naval opposition and with considerable success in enemy territory.

Archidamus invaded Attica again in the early summer of 430 BC and achieved little more than in 431 BC. This was to be the longest of the five occupations, lasting about 40 days and penetrating furthest, as far as Laurium; strangely there is no record of any damage done to Athens’ silver mines in this area, which would have had much more impact than the destruction of a year’s harvest in the surrounding fields, vineyards and orchards. However, plague, possibly a virulent mutation of typhus or typhoid, broke out within the walls. This first epidemic was to last for the best part of two years and would kill a far greater number of Athenians, Pericles amongst them, than enemy action.

The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, showing the progress of the ongoing restoration in May 2010. The original building was begun in 447 BC and replaced the slightly less grand temple begun after Marathon but unfinished when the invading Persians destroyed it in 480 BC. It powerfully symbolizes the 5th-century flowering of Athenian culture and also the imperial power of the Periclean state. Like the other great public works of this period it was funded by tribute money.

In contrast with Athens, the city of Sparta was an unwalled cluster of large villages in the valley of the river Eurotas, sheltered by the massive Taygetus mountain range. Modern Sparta, seen from the late Byzantine city of Mystras, covers much of the same area as the ancient city.

The Athenians’ tactical response at home was the same as in 431 BC. Overseas operations were less extensive, limited to Chalcidice and the continuation of the siege of Potidaea, now in its third year of resistance and finally starved into surrender that winter. The Spartans attempted to take the island of Zacynthus without success. According to Thucydides, and not surprisingly, ‘with their land laid waste a second time and plague and war weighing heavily on them, the Athenian people’s mood had changed. They blamed Pericles for making them go to war and for the misfortune they were now suffering, and were eager to agree terms with the Spartans. They even sent an embassy but it achieved nothing.’ (II.59) Pericles successfully persuaded the people to continue on the course he had set, reminding them above all of their invincible sea power. They made him pay a heavy fine ‘but soon afterwards, as is the way with the mass of the people, they elected him general again and placed their trust in him completely’ (II.65). When he took office again in the summer of 429 BC, Pericles was already sick with the plague.

That year Archidamus did not invade Attica but took his army to Plataea. His main purpose was to bind Thebes into the Peloponnesian alliance, but he may also have hoped to provoke the Athenians into confronting him there. The Athenians did not react, clearly feeling they had fully met their obligations to their faithful ally. Although Potidaea had been secured, Chalcidice was still out of control. A force of 2,000 hoplites, 200 cavalry and supporting psiloi were sent out to subdue it and were badly mauled at Spartolus. Although the Athenians won the initial hoplite engagement, they were then overwhelmed by superior non-hoplite numbers, including peltasts. First they routed the Athenian light-armed troops and cavalry, then ‘whenever the Athenians charged, they fell back and, when the Athenians withdrew, they closed with them and threw javelins at them’ (II.79). The Chalcidian cavalry completed the rout.

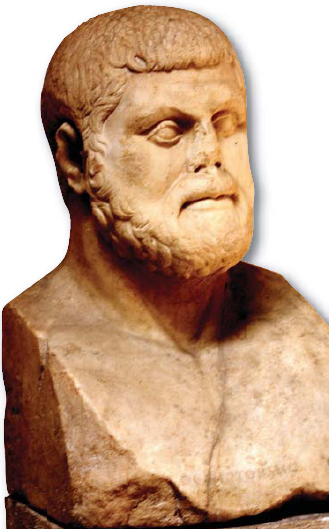

Pericles (c.495–429 BC), a 2nd-century AD Roman copy of a Greek original, which was probably made in the 420s BC. However, unlike the Ostia bust of Themistocles, this is not thought to have been a life portrait but an idealized image of the supreme citizen. British Museum.

Spartan hoplites had a similar encounter with missile troops in the same year, in an unsuccessful invasion of Acarnania. The Peloponnesians wanted to control this area, not least because the beaches and harbours could serve the Athenians as bases from which to mount attacks on the northern and western shores of the Peloponnese. Advancing on the city of Stratus the Spartan hoplites were pinned down and forced to withdraw. ‘The Stratians did not engage with them at close quarters … but shot at them with slings from a distance and made things very difficult for them because they could not make a move without the protection of armour’ (II.81).

This tender relief from a gravestone found in Athens is dated to the decade of Pylos and Sphacteria and the two great epidemics of plague. These, and probably also the increasing combat death toll, brought about a revival of this art form and took it to new heights of expression and sophistication. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

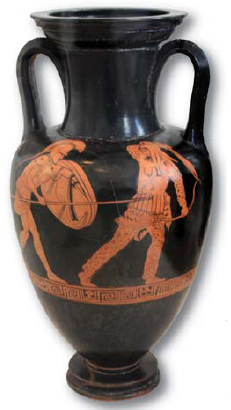

Peltasts, fierce javelin-warriors originally from Thrace, were mobile and versatile specialist troops. They took their name from the pelte, the light, crescent-shaped shield that Amazons are often depicted carrying. They were much more effective than the crude mass of the psiloi and, as assets, on a par with specialist archers and slingers. They were deployed on both sides in the Peloponnesian War and wore distinctively patterned tunics, cloaks and boots. The light helmet with turned-up earflaps in this image is an unusual alternative to the more typical soft fox-skin cap. Ashmolean Museum. (Ashmolean)

Support for the Spartans in Acarnania had been on the way. A fleet of 47 triremes and some smaller ships was sailing west along the Corinthian Gulf with 1,500–2,000 hoplites on board, but was intercepted by a squadron of 20 Athenian triremes out of Naupactus. Phormio, the general in command, launched his attack in the more open water of the Gulf of Patrae to exploit to the full the ‘better sailing’ qualities of his ships (better construction, speed and manoeuvrability, better steersmen and crews, better rowers); the Peloponnesian triremes were at even more of a disadvantage because they were being used as troop-carriers. Phormio literally ran rings around them and captured or disabled at least 12. (II.83–4) The Spartans put this defeat down to incompetent leadership rather than their fleet’s general lack of battle experience and inferior quality, and sent three senior commanders, one of them Brasidas, to oversee operations.

Both sides anticipated further action and called up reinforcements. Twenty triremes were immediately sent from Athens, but were unhelpfully given a mission to carry out in Crete first and arrived too late. The Peloponnesian fleet, reinforced and now better drilled in battle-manoeuvres, sailed from its temporary base in Cyllene on the west coast of the Peloponnese to Panormus on the south side of the Gulf to link up with the Peloponnesian land force that had arrived to support it. Phormio was now facing 77 enemy ships and the Gulf was about a kilometre across across at this point. He was unwilling to give battle in this tight space, whilst the Peloponnesians would not risk another engagement in more open water.

After a week of inaction the Peloponnesians moved eastward along their side of the Gulf in column of four to threaten Naupactus. Phormio took his ships along the northern shore in single file with his own hoplite support, Messenians from Naupactus, keeping pace with them on land. When both sides had covered about 4,000m, the Peloponnesians suddenly swung from column into line and bore down on the Athenians in an attempt to cut off the whole squadron. It is tempting to give Brasidas the credit for this well-rehearsed tactical move and it was initially half-successful, trapping nine ships against the shore.

However, some of these were recaptured by Messenians dashing into the sea and boarding them. Ten of the 11 that got away reached Naupactus well ahead of their pursuers and formed up in close order to defend the harbour. A Leucadian ship that had pulled ahead of the rest of the Peloponnesians was gaining on the 11th. But the Athenian trireme made a tight turn around an anchored merchant ship and rammed the Leucadian from the side, putting it out of action. The Peloponnesians following were so shocked by this that they dug in their oars and came to a halt. Not knowing the area, some ran onto shoals and the remainder drifted out of formation and within easy striking distance of the Athenians. The 11 Athenians immediately darted out and drove them off, capturing six and recovering the ships they had lost initially.

This was an extraordinary victory for the outnumbered Athenians and a humiliating defeat for the Peloponnesians; Thucydides records that one of the three Spartans sent out to get a grip on the campaign happened to be on the unfortunate Leucadian trireme and killed himself for shame. With the summer coming to an end, the elements of the Peloponnesian fleet that had been supplied by Corinth, Megara and Sicyon sailed back to the eastern end of the Gulf and the rest dispersed.

The commanders of the Peloponnesian fleet decided to launch an attack on Piraeus; Brasidas may have been influential in the planning of this operation, which, in conception at least, stood out from the Spartans’ rather pedestrian conduct of the war to date. They were encouraged to do this by the Megarians, who offered them the use of 40 ships from their eastern seaport, Nisaea. 8,000–9,000 men, including 6,800 rowers, walked across the Isthmus and launched this fleet under cover of darkness. Losing their nerve, or held back by adverse weather conditions (the two explanations Thucydides offers), they only made the short crossing to the west end of the island of Salamis. They captured three triremes and the small fort there and went on to plunder and lay waste most of the island. This caused great panic in Athens and Piraeus.

The Athenians immediately mobilized to defend the port and prepared ships to cross to Salamis at dawn. The Peloponnesians rapidly withdrew with their plunder and prisoners. Thucydides thought they could easily have mounted an attack on Piraeus ‘if they had had the will and had not shied away from it; a bit of wind would not have stopped them’ (II.94). However, he reveals a little later that the Megarian ships had been out of the water for a long time and so were leaky. Even if they had managed the longer crossing to Piraeus, they would have been slowed up by the water taken in and no match for the Athenians.

During the winter Phormio took some of his fleet to Acarnania and marched inland with 800 hoplites to reinforce support for Athens. Pericles died of plague that September. The strategy which he had set and held to, while successful in defensive terms, had shown no sign of persuading the Spartans to abandon the war inside the anticipated maximum of four years, and the exceptional financial resources which had made the strategy possible were now dangerously depleted. No alternative strategy had emerged.

In 428 BC, ‘just as the corn was ripening’, Archidamus led his Peloponnesian army into Attica for the third time and the Athenians stayed behind their walls as before, avoiding a full hoplite confrontation. ‘Their cavalry, as usual, mounted attacks whenever they could and prevented the mass of psiloi leaving the protection of the hoplites to lay waste the land close to the city, following the established pattern. The Peloponnesians stayed as long as their provisions allowed, then withdrew and dispersed to their cities.’ (III.1) There were operations again in the northeastern Aegean and on the west coast of central Greece, and Plataea continued to hold out.

The Greek word for a light-armed soldier was psilos, literally ‘bare’ or ‘naked’. This one is using a cloak as a shield and his weapon is a cudgel. Athenians from the lowest citizen class and non-citizens served as troops of this kind, as well as serving as rowers in the fleet. They took on both roles in the Athenian navy’s frequent raiding missions around the coast of the Peloponnese. British Museum.

In spite of the continuing plague epidemic the Athenians were planning to send 40 triremes on the customary retaliatory cruise round the Peloponnese. Instead they sent them to blockade and lay siege to Mytilene, the leading city on Lesbos, to prevent this important source of revenue and naval assets going over to the Peloponnesians. A smaller fleet of 30 ships was sent round the Peloponnese to raid Laconia and afterwards to sail north and attack Peloponnesian allies on the southern borders of Acarnania. Failing to capture Oeniadae, its main objective in Acarnania, the fleet sailed on and made a landing on the island of Leucas; this operation ended in defeat.

The Spartans, reckoning that Athens was now dangerously overstretched, decided to attack Attica and Athens again, this time by sea as well as by land. They summoned their allies to assemble at the Isthmus in force. ‘The Spartans arrived first and prepared to drag their ships on rollers over from Corinth to the shore on the Athens side so that they could attack simultaneously by land and sea. They set about this energetically, but their allies were slow to muster because they it was harvest time and they were weary of campaigning.’ (III.15)

The Athenians countered by manning 100 ships, drawing on the entire citizen body, only excluding the very rich, and also on the resident-alien section of the population, and sending them to cruise down the Isthmus and raid the north-eastern shores of the Peloponnese. This unexpected show of strength and the non-appearance of their allies left the Spartans with no option but to withdraw. The Athenians were then able to send reinforcements to Lesbos under the command of the general Paches but, exceptionally, each of the 1,000 hoplites had to take an oar in the ships they sailed in. Thucydides notes that Athens, with her naval strength at its peak, had 250 triremes, their complements totalling around 50,000, on active service that summer; he also comments on the unsustainable level of expenditure that this and the Lesbos expedition entailed. Despite all the activity, there still seemed to be no prospect of either side bringing the war to a conclusion.

During the winter, with food running low and no prospect of relief, half the tiny garrison of Plataea made a daring escape over the encircling wall. So the war continued into 427 BC. Once again the Spartans invaded Attica, doing more damage to the countryside than in any year except 430 BC, but as usual they failed to provoke the Athenians into marching out against them and withdrew when their supplies ran out. The Spartans also sent a fleet of 42 ships to support the Mytileneans but its ineffectual commander, Alcidas, took the crossing of the Aegean very slowly and was only halfway there when he received news that the city had fallen. He continued east to the coast of Ionia where he could have seriously threatened Athenian interests, but took no action and was soon chased back west by Paches.

On this gravestone two Athenians bid each other farewell in the presence of a priest. The heavy shield and spear (the top and bottom of that carried by the middle figure would have been painted on) define them as hoplites. The open pilos-style helmet had generally superseded the classic Corinthian helmet decades before, and body armour and other more closed styles of helmet were much less frequently worn. Antikensammlung, Berlin.

The Athenian Assembly famously and just in time reversed its decision to execute the entire adult male population of Mytilene, a reprisal forcefully advocated by the popular leader, Cleon. However, over 1,000 prisoners from the anti-democratic faction judged to be most responsible for the rebellion were killed. When Plataea finally gave in to starvation and surrendered, the Spartans had the surviving 200 Plataean and 25 Athenian defenders executed after a show trial. The war had grown more vicious.

Next, Athens and Sparta became involved on opposite sides in civil war in Corcyra. A small Athenian fleet, 12 ships carrying 500 Messenian hoplites from Naupactus arrived first to support the governing democrats against the oligarchic faction that had attempted to take over. The situation was contained but a few days later the Peloponnesian fleet arrived. It had been stationed in Cyllene since the Ionian fiasco. Alcidas was still in command (strangely, the Spartans were much more forgiving of failure than the Athenians) but Brasidas was also on board in the same advisory and supervisory capacity as in the Gulf of Corinth the previous summer.

The Corcyreans hastily launched 60 ships and sent them out piecemeal to face the Peloponnesians, ignoring Athenian offers to take the lead. The Peloponnesians left 20 of their ships to face the Corcyreans’ shambolic attack and the remaining 33 bore down on the 12 Athenians. The Athenians not only avoided envelopment but also attacked one wing of the enemy formation. With one ship rammed and disabled the Peloponnesians lost their nerve and formed a defensive circle. The Athenians adopted the same tactic as off Naupactus the previous year and circled around them threateningly, with the aim of disrupting their formation. The rest of the Peloponnesians, perhaps led by Brasidas, saw the danger and broke away from the Corcyreans to take on the Athenians.

Acknowledging that odds greater than four-to-one were too much, even for 12 of the finest warships and crews in the world (including Athens’ very best, the state triremes Salaminia and Paralus), the Athenians decided on a tactical withdrawal. Thucydides, who had commanded triremes during his time as a general, concludes his account of the battle, ‘They backed off with their prows always pointing at the enemy, going at a leisurely pace to ensure that the Corcyreans could pull clear while the Peloponnesians were formed up to face them’ (III.78). The Athenian squadron suffered no loss but the Peloponnesians were able to tow away 13 Corcyrean ships. The city was in a state of panic after this defeat.

Brasidas tried to persuade Alcidas to exploit the situation but all he did was order a landing on the opposite end of the island to lay waste some farmland. Then the Peloponnesians learned by beacon signals of the approach of a larger Athenian fleet. Earlier the Athenians had managed to prevent the democrats massacring their oligarch enemies but now they could no longer restrain them, or they simply stood back and let it happen because, of course, the elimination of local opposition was in their interest. Late that summer, for the first time Athens committed troops and ships to a campaign in Sicily, supporting Leontini in its conflict with Syracuse, but with the longer-term objectives of denying the Peloponnese Sicilian corn and bringing the whole island into the empire. This was the first move towards a more aggressive and proactive war plan.

Over the winter, plague flared up again in Athens. The population of Athens and Attica in 431 BC has been estimated to total 300,000, and a quarter to a third may have died of the disease. In 426 BC the region was also hit by earthquakes, and because of this, the Peloponnesian force assembled for the annual invasion turned back at the Isthmus. The Spartans attempted one strategic initiative, planting a colony at Heraclea near Thermopylae. Their aim was to establish a secure staging post on the land route to Thrace and a base from which to raid Euboea. This was unsuccessful, due in part to Thessalian resistance to a potentially powerful new presence in the region, in part to Spartan mismanagement.

The Athenians had some successes through the year in Sicily and one defeat at the hands of the Syracusans. An expedition under the command of Nicias made an unsuccessful attempt on the island of Melos, which was neutral but with Spartan sympathies. However, before returning home Nicias sailed north, linking up with a force that marched from Athens to Tanagra in Boeotia, and won a local battle there, avoiding facing the Thebans in full force.

Maintaining strategic focus on the north-western theatre, Demosthenes, one of the ten generals for the year 427/6 BC, was given command of 30 ships to campaign against Sparta’s allies along the west coast north of the Corinthian Gulf. Gathering reinforcements from Athenian allies in the region, he initially attacked the island of Leucas, advancing on the main city with enthusiastic support from the Acarnanians, the Leucadians’ mainland enemies. However, the Messenians that had joined him from Naupactus persuaded Demosthenes to put the forces now at his disposal to better strategic use by invading their enemy, Aetolia. They assured him that the scattered, backward Aetolian tribes lived in ‘unwalled villages’ (so did the Spartans!) and could be easily defeated. Though tough and warlike, ‘they used light weapons’ and were disunited. By subduing the Aetolians, he would remove a constant threat hanging over Naupactus and secure new alliances in this part of north-west Greece.

Demosthenes was particularly attracted by the prospect of then being in a position to attack Sparta’s powerful Boeotian allies from the west. He therefore abandoned operations on Leucas and, ignoring the objections of the Acarnanians, moved on to the port of Oeneon on the western borders of Aetolia. The several hundred hoplites and approximately 120 archers from his ships and a body of Messenian hoplites formed the nucleus of his force: the Acarnanians refused to be part of it. The Locrians were to follow and link up with him in Aetolia, bringing ‘knowledge of the country and local ways of fighting’. The operation went well for the first three days with the easy capture of three towns. However, the Aetolian tribes, against expectations, were now beginning to unite to oppose him in force.

Encouraged by his initial success and urged on by the Messenians, Demosthenes pressed on towards a fourth centre of population, Aegitium, without waiting for the Locrians to join him and remedy his dangerous lack of light missile troops. If, as is likely, his force also included rowers and other crew from his ship as psiloi, they were not the specialists he needed. Aegitium was easily taken. Then the large army that had now been assembled from the various tribes attacked, charging down on Demosthenes’ force from all sides and showering it with javelins and other missiles. The Aetolains fell back whenever the Athenians counterattacked and came on again when they fell back. The Athenians were soon struggling, but managed to hold out until the archers ran out of arrows. Before long the now exhausted hoplites and any light-armed support that was left broke and ran. Their Messenian guide had been killed so many became lost and separated in the forest paths and dried-up stream beds, and were hunted down by the more mobile Aetolians with their javelins.

To add to this nightmare, some of Demosthenes’ men became trapped in dense forest, which the enemy then set on fire. The casualties included the exceptionally heavy loss of up to 40 per cent of the Athenian hoplite contingent, Demosthenes’ fellow general and many of the allied troops. Demosthenes and the other survivors retreated with difficulty to the coast. He sent his ships back to Athens but stayed behind himself, fearful of his fellow-citizens’ reaction and the real prospect of exile or even worse. (III.94–98)

Athenian cavalry played an important role harassing the invading Spartan armies and supporting morale inside the city walls by protecting countryside nearby. The Spartans were slow to realize that cavalry might be of use protecting their coastline from Athenian raiders. This relief is from a public memorial to the Athenian war-dead in the early 4th century BC. Cavalry was ineffective against hoplites in close formation but lethal if this was broken. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Within a few weeks of their victory at Aegitium, the Aetolians persuaded the Spartans to support a counterattack on Naupactus, sending 3,000 allied hoplites under the command of a Spartiate, Eurylochus. However, he did not go directly for Naupactus, which was weakly defended and this gave Demosthenes time to make his peace with the Acarnanians and raise a force of 1,000 hoplites to reinforce the Messenian garrison. This was enough to persuade Eurylochus that the city could not be taken and, with winter coming on, he turned his attention to the north-west where the Ambraciots had invited him to attack Athens’ allies, including Amphilochia and Acarnania, from the north. The opposing armies faced each other near Olpae. Demosthenes joined his allies with 200 Messenian hoplites and 60 Athenian archers, the latter possibly from a squadron of 20 triremes that had arrived in the Gulf of Ambracia. Demosthenes was voted commander of this quite significantly outnumbered force.

After five days of inaction the two sides formed up in phalanxes in the conventional way to give battle. Demosthenes made it easy for Eurylochus to outflank his right, which he personally commanded, comprising his Messenian contingent and a few Athenian hoplites. However, he had concealed a 400-strong mixed force of hoplites and psiloi along an overgrown sunken road that ran roughly parallel to the battle lines and behind Eurylochus’ position. When the two phalanxes came together and the Athenians and Messenians were about to be enveloped, the ambush force charged into Eurylochus’ left from behind and routed it. His centre then also collapsed. His right, made up of Ambraciots, was initially more successful and put Demosthenes’ left to flight but was then demolished by the Acarnanians from his centre. Demosthenes then learned that a larger Ambraciot force approaching, unaware that the battle had been fought. He dealt with this decisively by making a night march and attacking at dawn ‘when they were still in their beds’. Any Ambraciots that got away were mopped up easily by the Amphilochians, positioned to cover all escape routes and ‘well acquainted with their own country and psiloi fighting against hoplites’. (III.100–112)

The Athenian corps of archers, an asset unmatched by any other Greek city, was made up of mercenaries from Crete and Scythia, and some citizens, resident aliens and, probably, slaves. They served in both navy and army and also as police. As here, they were usually depicted in exotic Asian dress and were looked down upon as an inferior kind of warrior by the hoplite elite, especially the Spartans. British Museum.

Demosthenes could return to Athens with his reputation repaired and enhanced, and having acquired battle-experience that would be critical to success in his next campaign.

The already lengthy and global conflict, in terms of the Greek world, between the Athenians and the Spartans had brought warfare a long way from the simple model of the conventional hoplite confrontation ‘on the clearest and most level piece of ground’ (Herodotus VII.9), as ridiculed by Mardonius when arguing the case for the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC.