Demosthenes is generally considered to have been one of the best Athenian generals to serve in the Archidamian War. He was the architect in every sense of the Athenian occupation of Pylos and in command there for the entire summer. For the last few days, he nominally shared command with the politician Cleon.

Demosthenes’ first recorded campaign, in Aetolia the previous year, had ended in disaster. It is likely that he already had some experience as a commander and had acquired a good reputation. It seems he was appointed general on merit, because there is no indication that he had any affiliation to help him follow the political route to this important public office. However, what he specifically experienced on campaign in 426–425 BC, in defeat and in victory, undoubtedly shaped the tactical thinking that led to his triumph in the late summer of 425 BC. Thucydides’ account of Demosthenes’ campaigning in 426 BC builds a portrait of an accomplished tactician and strategist with strong leadership qualities that he could exercise as effectively over allies as over fellow-Athenians. He overreached himself in Aetolia but the fault may not have been entirely his. His good friends the Messenians gave him poor intelligence and the Locrians may simply have let him down.

In any case he redeemed himself spectacularly at Olpae months later. In 424 BC Demosthenes, as one of the two generals in command of an attempt to bring Megara back to the Athenian side, led a force of light-armed troops in a successful surprise attack on its eastern seaport, Nisaea. Megara was not taken because of the intervention of Brasidas, but Nisaea was held for the next 15 years. Demosthenes then led a thrust from the west in an ambitious pincer operation against Boeotia but his part of the plan ended in failure and the bloody Athenian defeat at Delium that winter was a consequence. Thucydides names Demosthenes as one of the 17 who ‘took the oath for the Athenians’ in 422–421 BC, in the treaty that ended the Archidamian War, but otherwise does not mention him again until he was sent as a general with Eurymedon on the doomed mission to reinforce Nicias in Sicily in 414 BC.

Eurymedon and Sophocles were the two generals in command of the fleet that took Demosthenes to Pylos. Eurymedon had commanded a larger fleet in 427 BC, sent to Corcyra to support the democratic faction in the vicious civil war that finally aligned the island with Athens. He was probably a veteran of previous campaigns, with experience of senior command, and his name, after the great victory over the Persians in 466 BC, suggests a family tradition of distinguished military service. He was in joint command of the army that marched from Athens to link up with Nicias’ seaborne force in eastern Boeotia in 426 BC.

In 425 BC Eurymedon and Sophocles failed to intercept the Peloponnesian fleet, leaving Demosthenes with his small garrison and handful of ships at Pylos with no naval protection for a couple of days. But they soon remedied that lapse, comprehensively demonstrating the superiority of Athenian seamanship. At the end of the Pylos campaign Eurymedon and Sophocles resumed their mission and finally reached Corcyra. Reinforcing the Corcyrean democrats, they attacked and defeated the oligarchic insurgents in their mountain stronghold. They stood back (a second time for Eurymedon) as the prisoners, who were supposed to be under their protection to be shipped to Athens for trial, were horribly massacred.

Then they took the fleet on to Sicily and wintered there. The following year the warring Sicilians made peace so they returned to Athens. They were charged with taking bribes to abandon Sicily rather than attempt to establish a foothold there as ordered, which would probably have been impossible without an alliance with one of the major Sicilian powers. Sophocles was exiled (the fate Thucydides was to suffer) and Eurymedon was heavily fined. Eurymedon died in battle in the Grand Harbour of Syracuse shortly before Demosthenes and Nicias were executed after the Athenian surrender.

Nicias was a competent but cautious general, regularly one of the board of ten, and a leading politician from the wealthy, propertied class. He was opposed to the aggressive imperialism and radical politics of Cleon and his lower-class faction, and his goal was to bring about peace with Sparta as soon as possible on reasonable terms. Thucydides mourns his death in Sicily in 413 BC as the cruel and undeserved fate of a man ‘whose whole life had been governed by virtue (arete)’ (VII.86.5), words that identify him as a paragon of the old-fashioned values that, in Thucydides’ view, Cleon did not reflect.

The historian introduces Cleon as the ‘the most aggressive of all the citizens’ (III.36) and later describes him as ‘a popular leader (demagogos) with great influence over the mass of the people’ (IV.21). He was a powerful orator and the first of a new breed of politicians who pursued their agendas in the Assembly and the law courts rather than through service in positions of responsibility. He became a general in 425 BC by accident. Much of the credit for the Athenians’ success in the Pylos and Sphacteria campaign belonged to Demosthenes, but it was Cleon who secured the Assembly’s support in principle for action to end the stalemate, and their authorization to take the specialist troops that Demosthenes’ plan called for. He served as general again in 422 BC and campaigned in Chalcidice with initial success. However, he was comprehensively defeated by Brasidas in front of Amphipolis and killed by a peltast in the rout. Ironically, Brasidas also died in this battle.

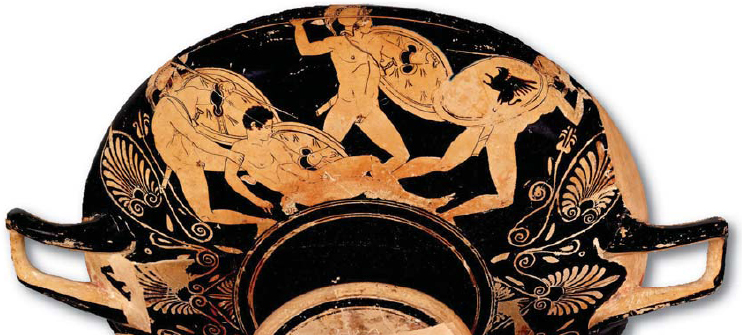

This Athenian red-figure pottery cup, dated to 420 BC, is unusual for the period because from 450 BC onwards painters seem to have depicted scenes of combat very rarely. On the rim, the style is anachronistically heroic with the hoplites nude and fighting over a fallen comrade. The double-grip system that made the heavy hoplite shield manageable is clearly shown. The helmets are of a form that lies between the closed Corinthian type and the pilos that was most commonly worn in the second half of the 5th century BC. British Museum. (British Museum)

Thucydides names only three of the Spartan commanders in the Pylos campaign, Thrasymelidas, Brasidas and Epitadas. All three were Spartiates, members of the warrior elite.

Thrasymelidas is only mentioned once, as admiral (nauarchos) in command of the triremes that made the attack on Pylos at the beginning of the campaign. He may not have been the only admiral, and whoever did have overall responsibility for the disastrous action in the Harbour two days later is not named.

Epitadas was in command of the 420 Spartans on Sphacteria and nothing else is known of him; he was probably at least of lochagos rank, a lochos having a ‘paper’ strength of 512.

Brasidas commanded a Spartan trireme in the abortive seaborne assault on Pylos, and according to Thucydides, displayed strong leadership. He may have had command responsibility for part of the fleet, applying experience acquired in the Corinthian Gulf earlier in the war. If he had not been wounded in the first action of the campaign, his continued involvement could not have prevented defeat in the Harbour but the engagement might have been less one-sided. Had he survived this, Brasidas would probably have injected some much-needed energy and tactical imagination into the Spartans’ not very proactive response to the situation which they were to face for the next ten weeks. From 424 BC until his death in 422 BC he rapidly built a reputation as a dashing and innovative commander and also as a highly effective negotiator and diplomat. His successful campaigning in northern Greece and Thrace took a number of important cities out of the Athenian alliance, including Amphipolis, the biggest prize strategically. Thucydides, a general in 424–423 BC, was punished with exile for failing to save Amphipolis from Brasidas (though he did manage to hold the nearby seaport of Eion, another attractive target) but admired the man greatly. Brasidas met his death successfully beating off Cleon’s attempt to recover Amphipolis for Athens. His successes left Sparta in a significantly stronger bargaining position than in late 425 BC for the peace negotiations that soon followed.

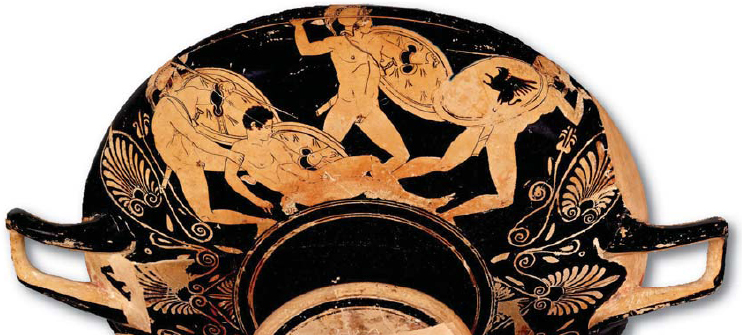

The inside image is contemporary rather than anachronistic. It is too damaged for a definitive interpretation but a conventional farewell scene would be less energetic and the two figures are clearly not fighting each other. They seem to be two comrades going into battle, both carrying spears. The figure on the right appears to have a shield but is bare-headed. The figure on the left wears a pilos, but it could be the universally worn felt hat that the bronze helmet was modelled on. If they are each holding their spears in their left hand (as shown in the Berlin relief in the case of the man on the right) they could be clasping right hands in a manly fashion. An intriguing possibility is that the figure on the left is a light-armed attendant. British Museum. (British Museum)

King Agis was in command of the Spartan army that occupied Attica briefly before withdrawing to deal with the occupation of Pylos, and it is likely he was at its head throughout that campaign. However, Thucydides mentions no one higher up the chain of command than Epitadas. The ultimate disaster caused the Spartans great distress and embarrassment and it may be that the historian is here paying a modest price for the goodwill of important sources. Agis’ greatest achievement was to lead his army to victory seven years later at Mantinea, the largest land battle of the conflict and, as it happened, one of the few classic hoplite engagements. He was also in command in 413 BC when the Spartans fortified and permanently occupied Decelea, a village (deme) in Attica, a base planted in enemy territory with exactly the same purpose as Demosthenes’ fort at Pylos. But this was only 24km from Athens and actually in sight of the city, so had significantly more tactical and strategic impact.