When the men had been brought back the Athenians resolved to keep them in chains in prison until some deal could be done, but to take them out and execute them if the Peloponnesians invaded their land before this. They established a garrison at Pylos and the Messenians from Naupactus, who regarded Pylos as homeland (for it was once Messenian territory), sent out some of their most effective troops from there to plunder Laconia, and they were able to do a lot of damage as they spoke the local dialect. The Spartans had no previous experience of raiding and warfare of this kind. Helots were deserting and they were afraid that this might lead to more serious insurgency across the land. They were very worried and, although they did not want to reveal this to the Athenians, they kept sending embassies in an attempt to recover both Pylos and their men. But the Athenians, always grasping for more, sent the embassies back empty handed as often as they came. (IV.41)

Thucydides here tersely concludes his 10,000-word account of the campaign, ‘This was what happened at Pylos’. The Athenians sailed back to Athens and the Spartans marched home. Thucydides does not say what the Athenians did with the captured ships that they had held at anchor in the bay for over two months. Triremes left afloat and neglected would deteriorate quite rapidly, especially any that were damaged or had already been at sea for a long period and some of them were probably not of very good quality in the first place. In any case, the Athenians would not have had the manpower to row them away, though they may have taken a few of the better hulls with them under tow. They probably left most of them behind to rot or perhaps burned them as a final gesture.

Nor does Thucydides tell us of any Spartan arrangements to contain or keep watch over the garrison and ships that remained. The fort was kept supplied by sea and probably served for the most part as a base for seaborne raids up and down the coast, because the closer hinterland was thinly populated and offered little in the way of assets to destroy or plunder.

Thucydides depicts the Spartans as reduced to near-paralysis at this time:

They were in a state of high alert, fearful of new threats to the established order of things. The disaster on the Island had been a huge shock; both Pylos and Cythera were in enemy hands, and they were hemmed in on all sides by a war that was fast-moving and unpredictable. Their attitude to military action had become even more cautious… The misfortunes that had come upon them, in such quick succession and against all reason, had filled them with dismay, and they were fearful that another disaster might happen, just like the one on the Island. As a result, they had lost confidence in their fighting ability and they thought that any move they made would lead to catastrophe. Their morale was shattered because they had previously not known failure. (IV.55)

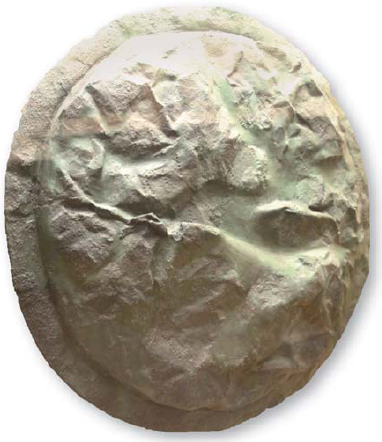

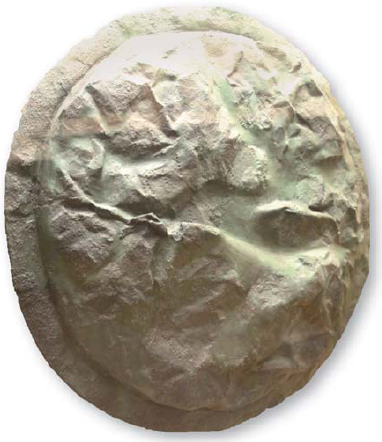

The bronze skin of a Spartan shield brought back to Athens as a trophy. It is tersely inscribed ‘Athenians from Lacedaemonians at Pylos’. Agora Museum, Athens.

The continuing occupation of Pylos, that ‘deserted spot’ and the imprisonment of 120 Spartiates might seem less serious than the threat posed by the fort at Methana, near Epidaurus and occupied by the Athenians that same summer, to important allies in a more densely populated and prosperous area of the Peloponnese, or by the capture (in 424 BC) of the strategically and commercially important island of Cythera, or, indeed, by the loss of almost the entire allied fleet. However, Pylos was more dangerous as a rallying point and refuge for dissident Helots and other natives of Messenia than as a base for pirate raiders.

Even more potently, it was associated with defeat and humiliating surrender. The same applied to the 120 Spartiates. Disgraced as they may have been, the Spartans wanted these men released and home. Some of them were from the most prominent families, who applied influence, and they were all surviving members of a warrior caste that was dying out. There were about 8,000 Spartiates in 480 BC according to Herodotus, 2,500 in 418 BC according to Thucydides, and less than 1,000 in 371 BC according to Aristotle. Reasons for this decline included the deaths caused by the earthquake of 465 BC and the subsequent Messenian War, and the unintended effect of rigidly applied inheritance laws. The Spartans were strongly motivated to make peace and prepared to make significant concessions in order to include the release of the Spartiate prisoners as a condition, even before they were taken off the Island.

The Athenians were not interested in peace but wanted to carry on the war, improving their already strong negotiating position by building on their recent success. However, things began to go wrong for them in 424 BC. After capturing Cythera they made a surprise attack on Megara; Demosthenes was one of the generals leading the operation. Brasidas, who was raising an army in the area of Corinth and Sicyon, intervened and saved Megara for the Peloponnesians, though the Athenians managed to hold on to the port of Nisaea.

They developed a grander plan to detach Boeotia from the Peloponnesian alliance that winter by invading simultaneously from the west and directly from Attica. Demosthenes was to lead the thrust from the west but the Boeotians found out about the plan and blocked it. The army from Athens carried out their part of the plan but was bloodily defeated at Delium, losing ‘their general, Hippocrates, just under 1,000 hoplites, and a great many psiloi and baggage carriers’. This was a large-scale hoplite confrontation with 7,000 on each side, but the Thebans on the Boeotian right did not follow the conventional pattern. They formed up 25-deep against the eight-deep Athenian left and ‘got the better of them, shoving them back slowly at first then putting them to flight’. The Athenian right did better initially but was then broken by a well-timed cavalry attack. Ironically, the quality of the Boeotians’ non-hoplite infantry, which included 500 peltasts alongside more than 10,000 psiloi, better organized and equipped than their Athenian counterparts, could have been a factor in their victory. (IV.93–96)

The goddess Nike (Victory) by the sculptor Paeonius. This was commissioned around 420 BC by the Messenians of Naupactus to celebrate their successes in the Peloponnesian War, including their involvement at Pylos and Sphacteria. Olympia Museum.

Meanwhile, Brasidas had made his way overland to Thrace, not setting foot in Attica and unable to go by sea. He had personally proposed this mission to undermine Athenian interests in the area and the government had given reluctant support in the shape of 700 Helot hoplites and funds to hire mercenaries elsewhere in the Peloponnese. He successfully forced or persuaded a number of cities, including the important colony of Amphipolis, to abandon their allegiance to Athens and, in early spring of 423 BC, Athens and Sparta agreed a one-year truce. The Athenians’ purpose was to put a stop to Brasidas’ campaign, which had been worryingly successful, and use the time to organize a response to it. The Spartans were well aware of this but had anyway anticipated that the Athenians would be more inclined to negotiate after Delium. For their part, they hoped that the truce would lead to negotiation of a longer-term peace and ‘the recovery of the men was an even higher priority while Brasidas’ run of success continued’ (IV.117).

The peace did not hold in Thrace. Brasidas engineered the defection of another city, Scione, before he had been informed of the truce but then neighbouring Mende also defected to him. Then, while Brasidas was away campaigning in Macedonia and Illyria the Athenians took Mende back and afterwards blockaded Scione; Nicias was one of the generals in command of that expedition. In summer 422 BC Cleon persuaded the Athenians to send him to Thrace in command of a strong force. He retook Torone before Brasidas could come to the assistance of the small garrison and then established a base at Eion, close to Amphipolis, where Brasidas consolidated his forces.

Thucydides’ brief account of Cleon’s and Brasidas’ final battle before Amphipolis probably takes a biased view of the generalship on both sides, but it is clear that the latter’s perfectly timed sally was decisive in his posthumous victory. Brasidas was one of the seven casualties recorded by Thucydides on his side whilst the Athenians lost about 600, including Cleon. The two leaders most opposed to peacemaking, as Thucydides observed, were now dead.

Neither side pursued the war any further and both were now inclined towards peace. The Athenians had taken a beating at Delium and again, not long afterwards, at Amphipolis. They no longer had the faith in their powers that had given them the confidence to reject earlier peace overtures, when they believed their current success would take them on to victory. They were fearful that their setbacks would encourage allies to defect in greater numbers and were now regretting that they had not agreed terms after things had gone so well for them at Pylos. The Spartans felt much the same. The war had not turned out as intended. They had expected to overcome the power of Athens in a few years by laying waste their land. Instead, on the Island, they had met with disaster on a scale that Sparta had never experienced before; their own land was being raided out of Pylos and Cythera; the Helots were deserting, and there was always the threat that those who remained in the Peloponnese might be influenced by those outside to exploit the situation and rebel, as they had done before… Both sides carefully considered all of this and came to the conclusion that it was best to agree terms. The Spartans were particularly keen to do so in their desire to recover the men who had been captured on the Island. (V.15).

Under its terms the Athenians were required to give back Pylos, withdrawing its Messenian garrison, and to release all prisoners, including those taken on the Island. The returning Spartiates were initially stripped of some of their rights but were later reinstated, so they did not receive the very harsh treatment they would have suffered in earlier generations. Pylos was occupied again in winter 419 BC and held for Athens till winter 409 BC. At Mantinea in 418 BC, a massive hoplite confrontation, the Spartans emphatically restored their fighting reputation in a victory over Argos, her old enemy, and her allies, including Athens. (V.65–75) The Peace of Nicias was meant to last for 50 years. It did not bring peace to Hellas, and Athens and Sparta were formally at war again in 414 BC.