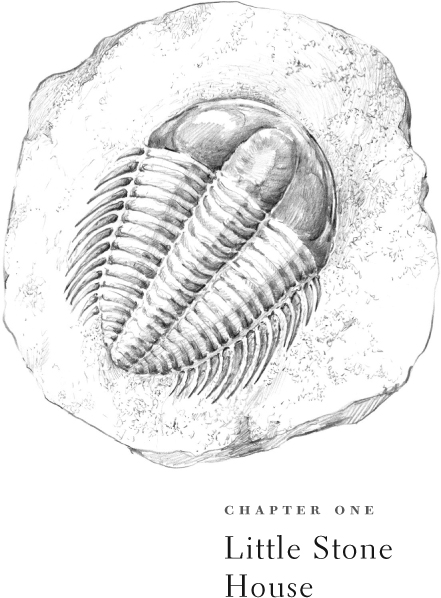

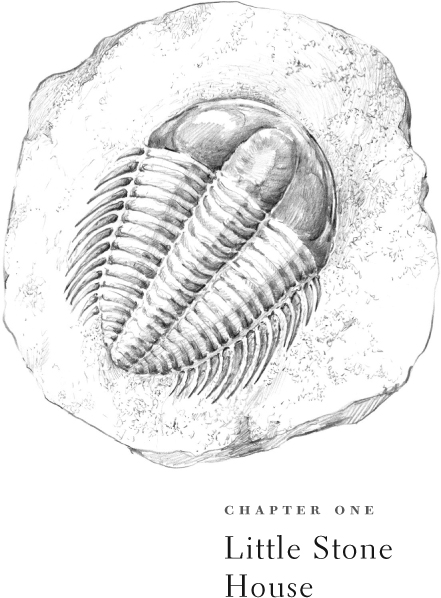

Upper Cambrian trilobite (Labiostria westropi) from Tanglefoot Creek

“LOOK FOR COOKIES,” Rolf had said, as he directed my attention to a tiny squiggle on a map of southeastern British Columbia. “Little round treats in the streambed.” He made it sound so easy.

By the time I reached Tanglefoot Creek on the west slope of the Rockies, I was beginning to wish I had waited until after spring runoff. Rising temperatures had loosened the snowpack from the nearby peaks, and the world seemed to be collapsing all around. A grinding porridge of mud and gravel sluiced bushes from steep rock faces. The creek, milky green in color, snapped like a racer snake, carrying chunks of my trail headlong toward the sea.

When I paused to check my progress, heavy drops of rain spanked down on my scrawled directions. I turned up a side rivulet that careened through a tight canyon, picking my way across a fresh mudslide. Clumps of saxifrage flowers, white stars touched with maroon and lemon spots, surfed atop thin plates of brown shale. Outcrops of the same shale shot steeply upward on either side of the creek; this was country that had been bent and twisted on a grand scale. Each step forward in space moved me backward in time.

The narrowing canyon finally forced me into the stream. I swapped boots for water sandals and plunged into the torrent. The water was so cold that I had to hop onto a boulder every few minutes to let the sting go out of my feet. Grabbing at gooseberry bushes to steady myself, I cast my eyes left and right to match the pace of the torrid runoff, searching for the remains of a creature long extinct. The first round stone I picked up turned out to be completely smooth. So did the next several dozen. A thrush’s song ascended leisurely over the creek’s icy roar, and a succession of hard showers rode in one upon the next. The bird sang many times before an emerging ray of sunlight caught the raised edge of a biscuit-shaped rock on the nose of a gravel bar. I bent down and wrapped my hand around it, feeling for ridges. Even before I lifted it free of the creek, my fingers told me I had found a trilobite.

I waded over to the bank and sat down to admire my prize. It proved to be a worn, warped specimen not much bigger than an Oreo. The three lobes that had once defined a living trilobite were squashed almost flat. The ribbed segments of its thorax showed only as black shadows on the dark green rock, and the code of spiny detail had been reduced to faint cracks. Yet as I squeezed the patterned stone, my body flooded with warmth. Under the spell of the thrush’s song, the ancient relic began to spin a tune all its own.

IT WAS A TALE that began long ago, back in a time when life existed only in the sea. Beneath the surface of a placid ocean that lapped at the edge of our ancestral continent, the trilobite riffled through the mud. Quill-like spines curved backward along the sides of its squat body. Multiple pairs of jointed legs propelled it forward. As it moved, articulated hinges along its back flexed and rippled like slats on a rolltop desk, and feathered gills along its upper legs combed oxygen from the water. Supple antennae twisted above its head, sensing the surroundings through fine lateral hairs. A pair of prismatic eyes bulged from its rounded head, keen enough to catch movements through the murky depths. A host of images would have flashed across those ancient eyeballs, for the trilobite’s home teemed with life. Spiny sponges and pedestaled brachiopods bloomed across the ocean floor, while exotic jellyfish floated in the water column, and segmented worms writhed through the mud. A medley of arthropods, with their jointed limbs and tough outer shells, scrabbled about. Other trilobites, more than a dozen species of them, fanned out across the seafloor habitats like wood warblers through a hardwood forest.

My little trilobite would have begun life as a pin-sized larva drifting in this sea. The tiny creature soon developed a hard calcite carapace that shielded its body. As the animal grew, that protective shell became tighter and tighter, until wrinkled sutures atop its head softened, then cracked open like a locust’s shell. Plates around the eyes and cheeks broke free, and the trilobite began to lever its way through the opening. Once released, it was as vulnerable as a soft-shelled crab until a new suit of armor came of age. Over the course of its life, the trilobite discarded many more shields, each slightly larger than the last. When death claimed the animal, its carcass joined those molted shells on the ocean floor. Far beneath the reach of waves and wind, bacteria converged to consume its soft body parts. A gentle shower of silt soon covered the empty shell with a blanket of fine mud.

Time passed. Rivers continued to sluice sediments into the sea. Inch upon inch of primordial goo sifted down atop the trilobite’s shield, and myriad ones around it, until they were buried thousands of feet deep. The accumulating weight of all that sediment flattened the trilobite’s skeleton and pressed the moisture from the layered silt. As mud was transformed into rock, a peculiar chemical reaction took place between the calcium in the trilobite’s exoskeleton and minerals in the surrounding mudstone. Crystals of calcite sprouted around the carapace, forming a rounded nodule with the trilobite’s shape perfectly replicated on its surface, as if embossed with the state seal of some ancient arthropodean republic.

Meanwhile, far above its crystalline sarcophagus, my trilobite’s kin still crawled, and the remains of countless more generations collected on the seafloor. As the oceans grew colder near the close of the Cambrian period, half a billion years ago, many long-established varieties faded into extinction. New families came into prominence, along with familiar forms of starfish, cuttlefish, bivalved clams, and corals. Jawless fish gave way to sharks, and primitive vegetation appeared on shore. Continents began drifting together to form Pangaea, sea levels rose and fell, climates warmed and cooled and warmed again. Insects took to the air, and amphibians established themselves on solid ground. In the sea, a different and less diverse suite of trilobites scuttled next to horseshoe crabs.

Then, around 250 million years ago, at the end of the Permian age, trilobites disappeared from the seas of our world. They had been part of the saltwater scene for over 350 million years, and then they were gone. Some of their arthropod relatives survived, and their distant cousin the horseshoe crab is with us still, but the trilobite tribe left no direct descendants. The entire evidence of their existence lay locked in vast stone cemeteries thousands of feet beneath the sea.

Tens of millions of years passed before Pangaea began to split apart, and the mechanics of continental drift triggered a series of tectonic collisions off the western coast of North America. Secure within its crypt, my trilobite was slowly nudged ashore. Millimeter by millimeter, it traveled hundreds of miles eastward and thousands of feet upward as the old seabed became a new mountain range. Many more years of grinding ice and rushing water exposed the seam of fossil-laden shale. At the twilight of the last great glacial epoch, the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers settled into the courses we see them run today, carrying the Tanglefoot’s flow from the west slope of the Rockies to the Pacific. Birds migrated north and south along the ridgetops, and herding mammals wore pathways back and forth across the Continental Divide. In time, people followed.

The rising waters of formal science did not touch the eroding shale up the Tanglefoot until the late 1950s, when a graduate student stumbled upon some fossils while doing fieldwork in the area. He and subsequent geologists described a lagerstätten—a trove of beautifully preserved specimens spilling out in an abundance that echoed that of the primordial sea. Paleontologists working at the site have since collected thousands of trilobites belonging to over a dozen different species, including two completely new to science.

THE GRADUATE STUDENT, it seems, was not the first visitor to pick up a Tanglefoot trilobite. Several years ago, a retired schoolteacher from southwestern British Columbia donated a collection of artifacts to a local confederation of Coast Salish tribes. The items, gathered along the lower Fraser River, included projectile points, scrapers, and knives; the tribal archaeologist noted that several of the pieces were of a sort associated with traditional burial sites. Present in the array was a biscuit-shaped stone that contained some kind of fossil. Rolf Ludvigsen, a paleontologist who directs a research institute in western B.C., was called in to have a look.

Ludvigsen instantly recognized a trilobite of a very unusual type. Furthermore, he knew the species, with its distinctive method of preservation, was found in only one place—Tanglefoot Creek, clear on the opposite side of the province, fully three hundred miles east. But the Tanglefoot belongs to the Columbia drainage, and there is no natural force that could explain how the fossil crossed to the Fraser River system. It could only have been transported across the watersheds by human hands. Ludvigsen speculated that the trilobite might have been picked up by a native traveler who either carried it on a long journey or introduced it into a trading network that eventually led to the lower Fraser. As a student of trilobite lore as well as morphology, he knew that such an occurrence was not without precedent.

Trilobite fossils are found on every continent, and the annals of archaeology hold evidence that these stone images have been catching the eyes of humans since Paleolithic times. An aboriginal tool uncovered in Australia had been chipped from a piece of chert containing a complete trilobite that retained enough distinguishing features to be identified as a new species.

At a rock shelter in central France now known as La Grotte du Trilobite, archaeologists excavating a layer of debris occupied by humans around fifteen thousand years ago unearthed an oblong facsimile of a beetle, carved from lignite coal. Near the beetle lay a worn trilobite. Both artifacts matched recognizable species of the Arthropod order, and both were perforated by carefully placed holes, presumed to have carried a string so that the ornaments could hang in necklace fashion. There is no way to know what these objects meant to their ancient crafters, but they must have been regarded as items of value. There must have been some attraction of design or shape that led curious hands to pick them up and carry them along, to modify them for specific purposes, to touch them over and over.

Folklore from around the world offers insights into the motives of more recent collectors. One small trilobite species found in a province in China has been used as a medicinal “swallowing stone” for centuries. Some Welsh people still carry the ribbed rear portion of an Ordovician trilobite that is shaped like a pair of wings. These “petrified butterflies” have long been ascribed to an ancient spell of Merlin.

In the early 1900s a natural history buff named Frank Beckwith was digging in traditional Pahvant Ute territitory in west-central Utah when he uncovered a human skeleton. Within the rib cage lay a fossil trilobite. There was a hole drilled through the head of the trilobite, and its position inside the chest cavity indicated that it must have been worn as a pendant. A nearby mountain range contained an abundant deposit of this particular type of trilobite, which a Pahvant Ute acquaintance called by a name that Beckwith translated as “little water bug like stone house in.” Upon inquiry, he learned that Ute elders used the fossils as cures for diptheria and sore throat, and wore them as amulets to afford protection in battle. At Beckwith’s request, a young tribal member fashioned a necklace following a traditional design. When complete, it contained thirteen trilobite fossils, each drilled through the head and strung on a rawhide thong between hand-formed clay beads and tassels of horse hair.

Back on the Tanglefoot, I turned over these stories along with the fossil in my palm, thinking of everyone who had touched those traveling trilobites—the Australian toolmaker, the wearers of the amulets, the Chinese physicians, the traveler on the Tanglefoot, the traders along the path, the schoolteacher, the scientists. I wondered how many of them had looked for more.

After a while, pulled by the lure of the search, I waded back into the snowmelt. The rushing water magnified the streambed into a swirling kaleidoscope. I plucked a random pebble and flipped it over. A mayfly nymph clung to the underside, its segmented body and bristling limbs echoing the trilobite form. The thrush sang on as I tested other rocks, pushing up riffles until my shins turned blue. But no more stone water bugs appeared in my hand.

A fresh burst of hailstones finally convinced me to call it quits. Shivering, I wiped the grit from my eel-white feet and re-laced my boots. On the trek back to my car, the single trilobite in my pocket began to bother me with the way it knocked against my leg at every step, and I stopped to draw it out. In the tired afternoon, the fossil had faded—its color dulling toward gray, the details of its anatomy sinking back into the stone. The word relic is rooted in the Latin relinquere, “to let go,” and I thought about that as I tossed my prize beside the path and continued walking.

Ten steps out, a fading whisper of “once upon a time” reached my ear, and I turned around to retrieve my trilobite from beneath a tangle of budding serviceberry. The grooves and lobes were still there, however faint. I burnished the stone’s bumpy surface with my thumb, slipped it into a different pocket, and carried on.