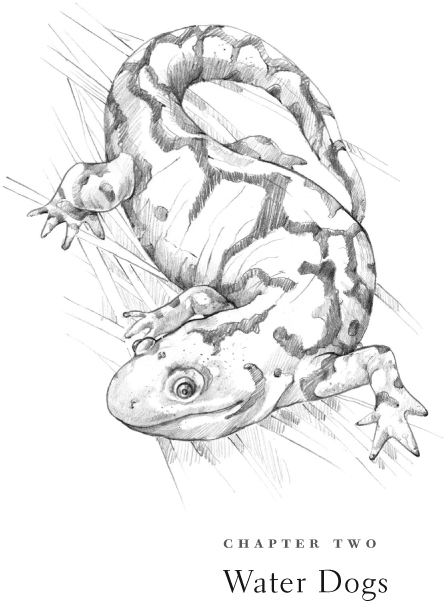

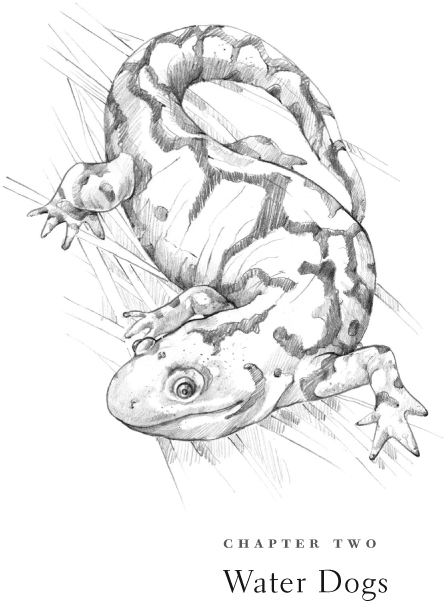

Adult blotched tiger salamander (Abystoma tigrinum melanostictum), after a sketch by George Suckley, 1855

ROBERT HAD BEEN RIGHT on the verge of trouble all week. A short sinewy boy, lined in the face beyond any of the other seventh-graders, he possessed the kind of energy that kept him wriggling in his desk all day long. I was a guest teacher at his rural school for a unit on natural history, and although Robert made no secret of his distaste for books, he was happy to talk about anything remotely connected with hunting or fishing. But whenever I cut him off to present an assignment, he would pull his black baseball cap tight over his eyes and slide down in his seat for a sulk that generally lasted past the bell. That pattern held until Friday morning, when we ventured outside for a field trip.

A cool spring fog hung over the river as the class ambled downstream toward the mouth of a small creek where, two centuries before, a group of Canadian fur traders had met an encampment of local Salish people. It was a comfortable walk, following long skeins of standing water bordered with many of the same berry bushes and wildflowers those earlier denizens would have known. We passed blooming camas lilies, and one of the tribal girls described digging their roots with her grandmother. We stopped to watch a cormorant make an underwater dive, and while the rest of us waited for it to resurface, Robert darted up and down the embankment, scratching through the grass like a buck rabbit. I was telling the class how the early traders sometimes ate the fat black birds for dinner when Robert motored up behind me, driving a battered steering wheel he had pulled from the weeds. “Hey,” he crowed, to the delight of his audience. “Think those mountain men left this behind?”

Beyond the trestle that spanned the creek mouth, we reached an expanse of floodplain. As their regular teacher and I herded the class through a gap in the fence, Robert veered off to peer into the opening of a large concrete culvert. “He’ll catch up,” his teacher assured me, and we pressed on.

The rest of the students had fanned across the grassland before Robert reappeared, his hands cupped in front of his chest as if carrying something fragile. The magnetism of discovery quickly drew his classmates back from the arc of the floodplain. Robert held his ground as they pressed around him, opening his hands to offer teasing glimpses of what appeared to be a dark-colored extra finger.

“It’s a lizard,” one boy announced.

“Don’t touch it!” gasped another. “Those things squirt out poison from their skin!”

Robert did not say a word. He spread one palm flat so that everyone could see his prize, then curled his mud-stained fingers as pickets against the small animal’s probes for escape. He drew a blade of grass down a wavy olive-green line that traced its sinuous spine.

“Thump its tail,” a tall girl commanded. “It’ll fly right off and dance beside the body.”

I was opening my mouth to counter this flow of misinformation when a smaller girl shouldered her way through the circle. “That’s no lizard,” she said calmly. “That’s a salamander.”

She held out a fisted forearm, and Robert carefully placed the creature on her wrist. It began to walk, slowly but steadily, toward the back of her hand.

“Look how smooth its skin is,” she instructed. “Anybody knows lizards have scales.”

The girl rotated her wrist so that Robert’s find stepped naturally into the protection of her palm. With her free hand she teased gumming bites from its harmless mouth, prompting a joke about a toothless grandparent.

“See, it won’t hurt anything,” she cooed. “I find these guys around our well house all the time.”

One of the boys stepped forward for a closer look. “Hey, I saw one of those things poking around in the snow up on the mountain.” He reached a tentative finger toward its head. “They’re supposed to be cold-blooded, right?” he said, gingerly touching the tiny snout. “How can they do that?”

Other students had encountered the creatures as well. A girl confessed that she and her brother had found a pair of salamanders in a window well and decided to keep them as pets; they installed them in a glass casserole dish, only to have them both disappear the first night. Months later they discovered one of them behind the sofa, perfectly mummified.

Several members of the class knew you couldn’t beat salamanders when it came to fish bait. Water dogs, they called them. One kid described the proper way to hook them, tugging at his own lower lip. He had an uncle who kept a washtub full down in his basement. “His are the kind with feathers on their neck,” he added proudly.

“Those are gills, stupid,” broke in the girl who held the salamander. “That’s because they’re just babies.”

From the corner of my eye, I had noticed Robert step back and fade from view during the early stages of the discussion. He had been out of sight for only a few minutes when he returned, clutching his baseball cap to his midsection. To his obvious satisfaction, the class quickly gathered back around him. This time he revealed a hat chock-full of writhing salamanders, with all shades of green amoebic stripes. An excited voice asked where he had uncovered such a bonanza.

“Oh,” he replied, playing it cool. “Around.”

When I started in on the wisdom of putting the fragile creatures back where he had found them, Robert cradled cap to belly, his black eyes burning with the twin fires of possession and purpose.

“Take them back?” he asked, incredulous. “I’m the one who found them.” Robert hugged his cap fondly, and a small smile of satisfaction creased his lips. “Besides,” he said, “me and my little buddies here got some fishing to do this afternoon.”

I’m not much of a fisherman, but I do like salamanders. From their slender builds and the green stripes down their backs, I had recognized Robert’s finds as long-toed salamanders, a species that I have uncovered everywhere from alpine lakes in Montana to rain forests on the Oregon coast. Yet you seldom see one of these secretive creatures, much less a hatful. Long-toeds belong to the aptly named family of mole salamanders (Ambystomatidae), who spend most of their adult life in solitude, hidden in burrows and crannies. Late every winter, as the ground begins to thaw, some unknown signal calls these hermits away from their catacombs. A few males begin to move toward the body of still water—anything from a puddle to a lake—where they began their lives. In succeeding days and weeks, pulses of other males follow. Some take to the water, but most seek shelter beneath any available cover. With the patience of hermits, they await the arrival of their female counterparts.

The writhing mass in Robert’s cap had told me that just such a spring congress must be afoot. As soon as school was over for the day, I went back to the mouth of the creek. I knelt beside the dank culvert and began gently lifting rocks and rotting branches. Within minutes, I had uncovered a small selection of long-toed salamanders. I picked one up, wondering if this might be the evening when the first females trickled onto the scene and drew the waiting males into the water. These are creatures of the night, and their annual courtship rites are seldom seen by humans. Witnesses describe ponds roiled by the frenzied pummeling of competing males, followed by the undulating courtship dances of mating couples.

I looked at the animal resting in my palm. It raised its head very slowly, as if surfacing from underwater. White stars glistened from its moist, inky flanks. Its head wavered momentarily, then bounced up and down. The salamander lifted a forelimb and spread four toes, each as fine as a stem of newly sprouted lettuce. The primitive wrist waved lightly in the air, its tiny digits reaching back toward the very beginnings of life on land.

The earliest known fossils that can be linked to salamanders appear in Asia, in rocks from the Triassic period around two hundred million years ago. When a volcano erupted in northern China fifty million years later, at the height of what we think of as the dinosaur era, a flow of lava overran a body of water not much larger than Robert’s puddle. Just as Mount Vesuvius captured the breadth of daily life in Pompei and Herculaneum, the Chinese eruption exquisitely preserved a cross section of aquatic life in one small pond. Within this microcosm lay bodies of about five hundred amphibians of all ages, from larvae to adults, whose skulls, limb proportions, soft tissue imprints, and unique fused wrists are remarkably similar to the skeletons of modern salamanders.

From these Asian beginnings, salamanders radiated onto every continent, specializing as they plodded across space and time. Icthyosaurs and pteranodons came and went, but salamanders crawled on. The mole salamander family apparently arose in North America around thirty million years ago; from a locus in the valley of Mexico, they have populated almost every available habitat across our continent. Geologic upheaval and climatic change have isolated populations, and a bewildering variety of species has emerged, but the changes are relatively subtle: Basic salamander design has remained pretty much the same since that volcanic eruption in China long ago. The creature in my hand was a living relic of that primordial past.

THE DECREPIT WINDMILL stood alone in the scablands of eastern Washington, surrounded by overgrazed rangeland. Its stubby tower rose only about twenty feet above the ground, and its direction vane hung limp behind a spokeless differential. Near the base of its ruined sucker pump, a slim ellipse of cattails indicated the presence of a viable spring, which had been scooped out to make a small pond. The Bureau of Land Management had recently built a fence around the waterhole to keep out livestock, and biologist Todd Thompson was interested in what creatures might be making use of it. Considering the spread of barren ground around the pond, it looked like a most unpromising place for amphibians. Todd looked around at the battered landscape and shook his head. “You never know till you take a look, though,” he said.

A curlew called from the open prairie as we slid down the short embankment in our chest waders and began to work our way through the suctioning silt, sloshing cold water near the tops of our bibs. A tree frog sang from the cattails, drawing an interested nod from Todd. April winds had blanketed the pond’s surface with a tangle of tumble mustard, and we began examining woody skeletons soaked green with algal scum. After several minutes I raised a stalk lined with individual opaque globes, spaced along the stick like small peeled grapes. Each globe held a round black yoke rimmed with white. With a quick glance, Todd confirmed that we were looking at the spawn of a tiger salamander, another member of the mole salamander family. Tigers range over much of temperate North America, but in the entire Northwest there is only one variety, the blotched tiger salamander, which occurs along the mid-Columbia and some of its drier tributaries.

Circling the pond, we found more egg-bearing branches than seemed possible for such a small area. “That’s one thing about salamanders,” Todd said. “They’re always going to surprise you.” He reached down and scooped up a tiny red shrimp. Todd has visited hundreds of pothole ponds in search of salamanders, beginning with a field trip when he was in fifth grade, and he remains eager to talk about their mysteries. “People’ve tried to correlate them to rainfall, pH, dissolved oxygen, and fish, but it’s hard to say what makes the difference. There are places where I find them thick as this one year, and when I go back the next spring—nothing. You just never know what you’re going to find.”

As we approached the cattails at the shallow end of the pond, we found an entirely different sort of jelly mass attached to the flotsam. These egg packets were smooth and limp, like stockings hung on a clothesline, with noticeably smaller eggs scattered throughout. When Todd held a branch up to the light, we could see that each ball enclosed an elongated creature with a wobbly line down its back and a tiny nub protruding from each side of its neck. These eggs belonged to a long-toed salamander. “See what I mean?” Todd exclaimed. “You’ll read in books that tigers are found in the sagebrush country, while long-toeds belong in wetter, cooler places.” But here they were, sharing the same scabland pond. Todd said he saw it every now and then, especially around the edges of the Columbia Basin. He was curious to see what would happen in the little pond beneath the windmill as summer wore on.

When I returned to the windmill pond two weeks later, its surface had changed drastically. The algae had retreated to the edges, and all the tumble mustard seemed to have sunk to the bottom. After several passes in my waders, I couldn’t find a single egg mass, nor were there any signs of swimming larvae. It was a situation that called for a dip net.

The first swirl of the net dragged up a big glop of pure mud that rolled off the black and white patterns of many backswimmers, leaving them to rattle around the edges of the mesh. After a few moments, other creatures began to separate themselves from the muck: small crustaceans, purple worms, and leeches that twisted like sensuous leaves. It took a while to see the salamander larvae, lying perfectly still, like small-caliber bullets embedded in the slime. Lots of them.

The first two hatchlings that I plucked from the mud sported tails that were little more than transparent fins. Small bushy gills sprouted from the sides of their necks, and developing organs were visible inside their clear swollen bellies. I thought, tentatively, that they might be little tigers. The next one I pulled out seemed smaller, with knobbed appendages in front of its gill slits that looked like the balancing poles used by tightrope walkers. According to Todd, the balancers were a sure indicator that this was a long-toed salamander. Trapped in the net, both kinds of larvae looked like creatures still in the process of being born; released back to the water, they proved swimmingly alive.

In mid-May I took my kids out and impressed them by netting several larvae with every muddy sweep. Both kinds of salamanders still looked very fishlike, except for obvious legs budding off the front quarters of their smooth bodies. Both had golden eyes always on the glare. The tigers had put on appreciable weight, and some of their heads had grown so broad that they resembled bullhead catfish. At dusk we watched several of the larger ones hanging in the water column, their luxuriant gills waving like palm fronds in a tropical breeze.

The life of a salamander larva is fraught with danger; the creatures that feast on them range from great blue herons to fish. But if there are no fish present—and many Columbia Basin ponds are either too small or too alkaline to support them—it is often the tiger larvae that represent the most voracious predators in the pond. Carnivorous tigers have been known to gobble up other amphibian eggs, larvae, and even adults of their long-toed cousins. And yet in potholes where both species occur, the two moles seem to break the rules of logical ecology by breeding at just about the same time and growing in the water together. Somehow, the smaller, less aggressive long-toed salamanders must avoid being eaten, because they remain common. One key adaptation appears to be their rate of change from larvae to adult.

By summer’s solstice, long-toed salamanders seemed to be a thing of the past—it was a tiger’s pond now. Three swipes of the net produced five slurping larvae the size and color of gherkin pickles. Since no more than a small fraction of these larvae could possibly survive the journey to adulthood, it didn’t seem like any great disturbance to borrow one of them for a while. We chose the biggest and most active pickle from the bunch and placed it in the bucket we had brought along, plucked a wapato plant that was sprouting nearby for shade, and headed home. Our captive was still very much alive when we transferred it to the miniature habitat we had prepared in a terrarium on the back patio. Its color was now a pure jade green infused with calligraphic lines. Recognizable digits crowned each limb—four on the front legs, five on the rear. Its silken gills, three to a side, were fringed with black lace and flowed like samurai decorations. Milky lips defined an outlandishly large mouth. We tucked the succulent wapato tuber into a patch of gravel in one corner of the tank and added a big scoop of mud from the pond to hold it down.

By the next morning the arrowhead leaves of the wapato had uncurled in glistening green, and a couple of its three-petaled flowers had burst into bloom. Below them mosquito wrigglers, a water scorpion, several striders, and multiple backswimmers were all carrying on as if they had never left the pond. The salamander, however, did not look so good. It seemed to be in shock, lolling and tilting in the water. Its belly was alarmingly distended. In the face of sudden movement, it would flail its roly-poly self down and out of harm’s way, then bob awkwardly back to the surface. We peered helplessly into the tank until I remembered a woman who had told me about helping her dad catch salamanders for bait when she was a little girl. She said he always made her ride in the back of the pickup on the way home, keeping the pail that held the day’s catch upright as they bounced toward town on rough dirt roads. Knowing that the larvae could gulp the sloshing water and choke to death, he taught her how to pick up any that appeared to be in trouble and use her fingers to massage their bloated bellies. She became an expert at burping them, laughing every time one expelled a mix of air and water with an audible bark—real water dogs.

Thinking of those swollen white bellies, I ladled our sick larva out of the tank and massaged its underside with my forefinger. Sure enough, a sharp burble escaped from its mouth. When I lowered the patient back into the water, it swam smoothly into the wapato leaves. We shooed the cat away and sat down in front of the glass to watch what might happen next.

MOLE SALAMANDERS, secretive though they may be, do occasionally appear among the oral and written records of the Columbia Basin. In the early 1900s, a Yakama elder told a story about Coyote journeying up the Teanaway River on the east slope of the Cascades. When Coyote came to a certain lake, he saw that the water was bad, and he decreed: “No salmon will come to this lake. Only nosh’-nosh will be here.” Coyote returned downstream and built a waterfall to stop the fish, and from that day on, only nosh’-nosh, the water dog, lived in the lake. There he grew to great size. The elder explained that these water dogs belonged to the salamander family, and added that they were never used as food by his people.

Tribes around the rim of the basin, including Cayuse, Walla Walla, Nez Perce, Spokane, Kalispel, Flathead, and Kootenai, all have words for salamander. Like the Yakama, these tribes never utilized the water dogs for food, but several do associate salamanders with the idea of bad or dangerous medicine. This could be attributed to the animal’s mysterious habits and confounding life changes, and such ideas are by no means confined to Native Americans. In European lore, salamanders spontaneously generate themselves from the flames of a household hearth, and their parts often figure in recipes for witch’s brew. In Japan, the word ryuu means both “salamander” and “dragon.”

The reaction of the Scottish botanist David Douglas was similarly ambiguous in the midsummer of 1826, when he followed a tribal trail that wound between scabland coulees and the Palouse Hills of eastern Washington, through “an undulating woodless country of good soil, but not well watered.” Douglas enjoyed the day’s ride with his usual fervor for new places, but his enthusiasm was somewhat dampened at suppertime: “We were obliged to cook from stagnant pools full of lizards, frogs, water snakes.” Many people, past and present, call any small four-legged animal of a certain shape a lizard. But since true lizards don’t swim, salamander larvae are the only creatures that really fit Douglas’s description.

Thirty years later, naturalist George Suckley made a beautiful drawing of a tiger salamander while surveying a railroad route along the Columbia, but apparently no scientist probed their larger range until U.S. Army surgeon Basil Norris paid a visit to the northern edge of the Palouse in early June 1886. During an investigation of the purported alkaline healing properties of Medical Lake just outside Spokane, Dr. Norris captured a couple of peculiar “reptiles, the species of which has caused so much controversy in a local way for years.” Seeking an authoritative opinion, he shipped the swimmers east to the Smithsonian, and a few weeks later he received a reply from its esteemed director, Spencer F. Baird.

Dear Doctor,

The specimen referred to in your letter of June 12th was duly received, and, on an examination, proves to be the larva, or immature stage of the salamander. It is one of the so-called water lizards, found in wet places, under logs and stones. We are very glad to get the specimen as it is considerably out of any range known to us. We should like to have more of these creatures as they are probably quite abundant in your neighborhood.

James Slater, a Tacoma college professor and salamander buff, paid a visit to the source of this early specimen in September 1930. In the town of Medical Lake he spent an afternoon searching for the local water lizards in vain. Looking for inside information, Slater spoke with a young man at the swimming beach, who promised that he and his friends could supply plenty of the “dog-fish” (meaning “fish with legs”) after dark. Sure enough, a little after eight a few local men gathered and kindled a bonfire before stepping into the lake to drag a seine net. To Slater’s delight, their pass captured a dozen larval salamanders.

As soon as that crew left, another group appeared. Slater learned that since July these men had been driving from Spokane and catching salamanders to sell as fish bait. “I suppose we should call them salamandermen instead of fishermen,” he wrote. While the professor pondered whether the creatures might be attracted by the light of the bonfire, the seiners brought fifty-five good-sized larvae ashore. The catch included two adults with the distinct dark and light pattern of the blotched tiger salamander. Slater made sure he got that pair for himself, and accepted a few of the larvae as well.

The leader of the Spokane seiners told Slater that year after year, colored animals started coming up in the net around August 10 and continued to appear until the season ended around mid-September. His personal record for salamanders taken was 159 in a single pass of the net, and 209 dozen in an evening. The creatures caught that night varied in length from three to seven inches, which he deemed about average. The salamanderman could tell that his quarry’s abundance was tapering off, and he figured this would be his last trip of the year. Before departing, he confided to Slater that the going price for water dogs at Spokane bait shops was fifty cents a dozen—not a bad take in the midst of the Great Depression.

AS WE DRIFTED THROUGH the dog days of summer, change was afoot in our terrarium. The wapato shed its white petals one after another, and the sepals formed round green seed pods. Our salamander larva took to lying on the surface of the water at dawn and dusk. It would ride at the level of the tangled weeds, then sink a bit, pushing away with soles and palms turned outward as if the water were a supportive wall. Sometimes it would stretch out all eighteen of its toes, with one digit on each side breaking the surface. Its eyes began to bulge from its head, growing from flattened inset disks into round buttons. Odd swellings appeared along both sides of its neck, and its gills began to shrink from the feather boas of their prime. Its body developed distinct dark patches that dripped into parallel bars, but the belly remained clear white, bordered by a beautiful pattern of black stipples. Sometimes it would make a snap that might have been feeding. Occasionally it would burp out an air bubble with the sound of an old man spouting a good stream of tobacco juice, as if it might be learning how to breathe. But most of the time it hung still, showing grave indifference to the activity that whirled around it.

Then came a day when we found our captive lying on the surface, completely motionless, supported only by plant fibers. At first the kids were sure it was dead, but they misted it with a spray bottle over and over until, with excruciating slowness, the patient swam to the far end of the tank and rested its head and shoulders on a flat rock just clear of the water. To our astonishment, we could see that its entire front end had assumed the eerie, varnished sheen of an Andean mummy. For the next several hours, it did not move one iota. In the cool of the evening, the larva slowly lifted its head. It was then we realized that we could no longer see its gills. The muscles along the sides of its neck flexed, and the gill slits pulsated visibly, but those outrageous feathers, for so long our larva’s most visible feature, had disappeared. I had read about amphibians resorbing their gills during metamorphosis, but nothing had prepared me for the fact that an appendage half as long as the animal’s body would disappear into its neck.

The salamander hung in limbo between infancy and adulthood, between life and death, between the worlds of water and land. Now nascent lungs had to inflate with small gulps of oxygen not just occasionally, but with a continuous rhythm. The membrane of skin had to make the switch from water to air. Limbs accustomed to swimming had to assume the posture of a tetrapod; a body made for floating had to comprehend gravity. The creature was undergoing a metamorphosis that defined its whole existence, a monumental event that reprised not only the life history of its species, but that of all amphibians, and of Earth itself.

The salamander still lay in a light coma when night fell, and the next morning it was nowhere to be seen. We searched for many anxious moments before spotting the tip of a tail peeking out from under a spruce bough in the dry part of the tank. When we lifted the branch, we found ourselves looking at a completely transformed creature. Its head, broad, smooth, and smiling, seemed to have expanded, while its body had shrunk as if tightly wound in plastic wrap. The phoenix rocked its big head forward and back. Its neck throbbed with slow but steady breaths. Fore and hind legs moved once, then again, very slowly.

Every morning for the next several days we found it in a different place, squeezed into a rock crevice or tucked beneath a slice of bark. Sometimes it flopped into its little pool and swam turtle style, matching strokes with arms and legs of opposite sides. In the light its skin glowed like the oiled parchment of an antique map, with sharply defined islands of mustard and ebony. Its tail assumed an elegant taper, and fleshy doughnuts surrounded those periscope eyes. My ten-year-old brought an earthworm from the garden and waved it in front of the salamander’s nose. Its head ratcheted up one cog, then another, then lunged forward and seized the prey. Taking a ritual bow, the salamander dropped its head and shook the victim with a single violent snap. It took several minutes for the two dangling ends of earthworm to disappear, with periodic gulps, into the soft crescent mouth.

At the end of August, after eight bone-dry weeks, a morning thundershower rolled across the scene, and raindrops pelted our desiccated world. Within moments the salamander had ascended to the highest tip of the spruce bough that decorated the terrarium. Its head wobbled back and forth with every new drop from the sky. One eye blinked. It was feeling air and moisture together, an animal made for rain. As succeeding nights grew cooler, I kept imagining all those larvae back in the windmill pond, now transformed into adults and preparing to leave the water to find a secure burrow or crevice for the winter. We decided it was time to return our captive to the wild.

Dust enveloped the car as we pulled up to the ragged windmill, leaving us to wonder once again how a creature that required moisture could survive in such a dry place. The pond had shrunk to a fraction of its summer size, and across its reduced surface, brown wapato leaves were covered with black dots of insect frass. Green tree frogs were still hopping all over the plants, but scoop after scoop of mud failed to bring up any salamanders. Then on one of the last sweeps, a familiar shape snaked through the net. It proved to be a beefy tiger larva at least six inches long and very broad in the head. Its gills were huge, and its legs were strong and flailing, but the eyes still lay flat, which lent it a mean, threatening look. It was a neotene.

The hormones that trigger metamorphosis do not always flow at the same time for all the salamanders in a pond, and some larvae may not transform for a year or even more. In certain cases, such creatures can reach sexual maturity without ever leaving the water, a state of retarded development known as neoteny. These morphs, which can grow to outlandish size, often act like monsters in the pond, preying on their own kind. It is sneaker-sized neotenes, flailing in the mud of disappearing ponds, that leave sageland farmers sputtering with cries of “walking catfish!”

The first known written mention of mole salamander neotenes came from the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, where sixteenth-century Franciscan monks traced stone carvings depicting a god named Xolotl. This deity bristled with extra body parts, especially odd numbers of fingers and toes, and it appeared to sprout layers of feathers from the back of its neck. When the Franciscans inquired into the meaning of the name Xolotl, native responses included water slave, water servant, water sprite, water monstrosity, water twin, or, most familiarly, water dog. Brother Bernardino de Sahagun, assigned to teach a group of Aztec youths, learned from his students that Xolotl was closely associated with the ajolote, an aquatic form of salamander that thrived in the necklace of canals and lakes that embraced Tenochtitlan. “Like the lizard, it has legs,” the boys told Bernardino. “It has a tail, a wide tail. It is large-mouthed, bearded.”

The students showed their teacher the strange gilled creatures, some up to a foot long, and explained that they provided an important food source in waters that supported few fish. “It is glistening, well-fleshed, heavily fleshed, meaty. It is boneless—not very bony; good, fine, edible, savory: it is what one deserves.” When, after forty years of labor, Brother Sahagun published his landmark account of Aztec culture and natural history known as the Florentine Codex, he included an entry with the title “Axolotl.” The accompanying illustration depicted a creature with four legs and flowing gills, accurately representing a creature exactly like the neotene in my net.

I let the big pond monster slither away, then returned to the car and fetched the bucket that held our much smaller, newly metamorphosed adult salamander. We walked around the pond to size up the situation. An area of cracked mud was crisscrossed with the tracks of coyote and badger, skunk and raccoon, and the three-toed prints of ravens, gulls, and herons. Any salamander that ventured out on this hardpan would be dancing at a predator’s ball. Across the way we spotted a badger burrow, and around from that a bank so steep we couldn’t imagine any salamander making the climb. But down on the cattail end, a nice pile of drain rock rested in a damp seep. The rocks were of different sizes, with plenty of gaps and crannies where a little animal could hide. That was the place we felt our little tiger salamander deserved; that was where we tipped the bucket and let our captive go.