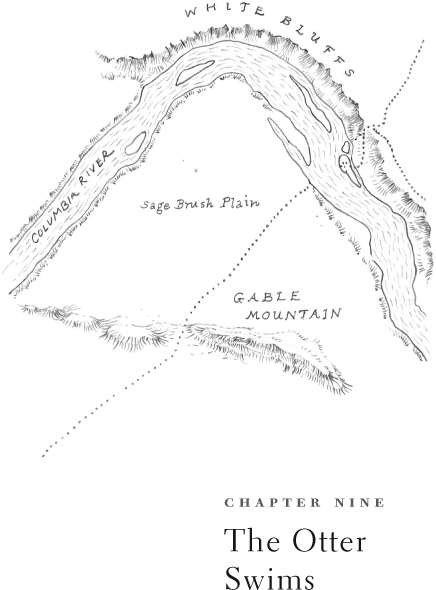

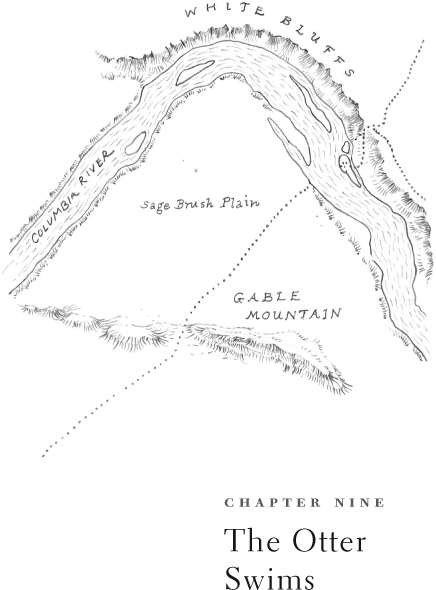

The old White Bluffs trail, after Alfred Downing’s Map of the Upper Columbia River, 1881

LATE IN THE twentieth century, the elegant hyperbola of the Trojan Nuclear Plant’s cooling tower rose as a signature landmark on the lower Columbia River. Steam pouring from its maw mirrored the concurrent activity of Mount St. Helens, and the plant, located on the Oregon side just upstream from the mouth of the Cowlitz, churned out enough kilowatts to light the metropolis of Portland. But after two decades of service, small faults began to plague its operation—a balky alarm system, a whiff of radioactive gas, and, as the last straw, cracked steam tubes that shut it down for good in 1993.

Six years later, the plant’s dissemination began in earnest. By then, the reactor vessel had already been stripped of its zirconium fuel rods, sealed at every orifice, and encased in a jacket of high-quality concrete. Eleven-foot foam impact limiters rimmed with stainless steel were attached to each end, then the entire package was wrapped in heavy blue plastic. All trussed up, the vessel resembled the stubby femur of some impossibly large mythical beast, weighing just over a thousand tons and measuring forty-two feet long by seventeen across. The two million curies of radiation inside the wrappings caused a stir of anxiety among some residents, although that figure represented only about 1 percent of the radioactivity in the spent fuel rods left behind on the Trojan site, and paled in comparison with the 185 million curies released in the Chernobyl incident. A General Electric spokesperson estimated that a person standing within six feet of the shielded reactor for one hour would catch about the same amount of radiation that an airline passenger received from the sun on a transcontinental flight.

The vessel was carefully loaded on a barge and pushed into the shipping channel. During the night, tugboat and barge cruised upstream past the bright lights of Portland, then hissed quietly through the locks at the Bonneville and The Dalles Dams, passing from the wet Pacific Slope to the sparsely populated lands of the interior. The shipment cleared John Day and McNary, and turned the corner at Wallula Gap. Early on Monday morning it reached the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers and chugged through the Tri-Cities to the Port of Benton, 270 river miles upstream from its starting point beneath the cooling tower. For the next nine hours, a curious crowd on the receiving dock watched as workers unbolted the 20-axle, 320-wheeled transport trailer from the barge, lowered the craft to meet the ramp, and hooked a mammoth tractor to the trailer’s hitch. It was early evening when the tractor towed its load up the grade to Horn Rapids Road, leaving considerable ruts in the gravel.

Once on the road, the crew held their speed to a steady pace of five miles per hour as they crossed the Pasco Basin. “You don’t want to get up any momentum of any sort,” commented the utility spokesperson. It was midnight before the trailer reached its destination near the center of the Hanford Reservation, where the relic from the nuclear age drew to a halt in the shadow of Gable Mountain, another relic from another time.

ON A HOT SUMMER AFTERNOON, sun rays bounce off the flat bottom of the Pasco Basin, casting a tangible haze. The illusion of a shallow iridescent sea spreads across the expanse, and it is the easiest thing imaginable to float away on the mirage, buoyed by the shimmering waves of heat, back through a couple of hundred millions of years to the edge of an ancient ocean, warm and swarming with life. During that long-ago time the copious remains of clams, snails, tube worms, and trilobites layered the seafloor with thousands of feet of marine detritus. To the east lay the solid land of the mother continent; from the west, groups of islands sailed in to collide with the mainland, riding atop a large tectonic plate that was sliding beneath the edge of North America. Ichthyosaurs swam in the huge bay encircled by these new additions, and pteranodons with ten-foot wingspans swept overhead.

The sea receded to the west, leaving a wide coastal plain. The air was warm and humid, and frequent rains pelted the land; streams and creeks meandered across the gently sloping surface, collecting to form the ancestral Columbia and Snake Rivers. A water-loving rhinoceros wallowed in lakes, while ancestral horses, camels, and elephants found their niches in this Eocene world.

Around twenty million years ago, clouds of steam appeared in the southeast, and a black wave of viscous lava rolled across the landscape, filling river valleys and lapping against the edges of the surrounding highlands, then cooling into a giant plate of dense basalt. The displaced Columbia wound along the northern edge of the flow, creeping through blackwater cypress swamps as it searched out a new path to the sea. Staggered pulses of magma spread new layers of hot lava across the region; again and again, the flows obliterated plants and animals and pushed watercourses back to the edge of the plateau. Time after time the Columbia cut a new course through the rock, and life inched back like a slow tide across the basalt. Eventually the flows abated to occasional trickles; by then the basalt measured thousands of feet deep, and its great weight had depressed the very crust of the earth.

Wrinkles appeared on the floor of the tableland like folds in an unruly cloth pushed from the southwest. The uplifts enclosed an irregular bowl near the western edge of the plateau, the beginnings of the Pasco Basin. Almost lost among the larger folds, a narrow ridge stretched for half a dozen miles across the building floodplain of the Columbia River. The river’s braided channels supported forests and open woodlands, providing habitat for a small deer with exotic mooselike antlers, a medium-sized ground sloth, and a panda that resembled its reddish relative that lives today in southeast Asia. Herds of Pierce’s peccaries plowed through the Pliocene vegetation, rooting for nuts. Occasional mastodons rumbled past. Eruptions of Cascade volcanoes dusted the basin with thick coatings of ash. On the edge of a pond, turtles plodded through the mud, surrounded by scuttling crabs; frogs croaked from the shallows, while catfish and sunfish flashed past. In the open river, white sturgeon cruised beside suckers and peamouth chub.

The growing Cascades cast a rain shadow over the basin. Grasses and shrubs covered the drier areas, providing food for lantern-jawed camels and the American Zebra, one of the first members of the horse family to develop that lock in the upper foreleg that makes it possible to sleep standing up. Bone-eating dogs roamed this world the way the hyena courses across the African veldt, as both predator and scavenger, competing for prey with a bear and at least two different cats. A weasel family member somewhat larger than our modern otter also worked the scene. Its rear molars rose and dipped in three sharply peaked crowns that inspired the species’ Latin name, Trigonictis. These molars might have nipped after ground squirrels, rabbits, young beavers, or fish; such a varied diet would have required an agile carnivore that could both climb and swim, one whose hunting ground covered a whole range of habitats.

The weather began to cool, and cold winds swirled off the lobes of the great ice sheets that slid down from the north. Many of the animals died off, and the river piled mud and silt over the last of their bones. Packs of bone-eating dogs remained to dine on holdover herds of camels along with Pleistocene mammoths, long-horned bison, and shrub oxen. As the glaciers began their final retreat, violent floods swept in from the east, transforming the Pasco Basin into a huge lake not once but several times. Successive deluges drowned the little ridge in its center until the water worked its way through Wallula Gap and downstream to the sea. Then the promontory peeked out across a flat-bottomed lake bed filled with gravel and sand, embraced by a semicircular curve at the bottom of the Columbia’s Big Bend. The small mountain, swept clean, stood at the heart of the great river.

THE LONG RIDGE THAT snakes across the pancake flatness of the Pasco Basin is labeled on maps as Gable Mountain, but the Wanapum people who lived in its shadow called it Nuk Say, The Otter. Indeed, when viewed from certain vantage points, a knobby head rises above the basin floor, followed by a rounded back; a sloping rump disappears beneath the surface for a mile, then a small butte mimics a broad tail flopping back into view. It is the shape of a playful paddler stretching up for a look around.

Climbing its rump on a breezy morning, I paused partway up the rocky slope to admire the graceful arc of the Columbia River sweeping across the foreground, touching three points of the compass as it curls south to meet the Yakima and the Snake. This section of river abounds in salmon and sturgeon, and people have netted fish here for at least sixty-five hundred years. I looked down at dark drifts of sand piled against The Otter’s flanks by the prevailing winds. Several years ago a pipeline surveyor taking a break on one of these dunes noticed a scattering of bone fragments and fire-cracked quartz. Archaeologists collected other artifacts that indicated a kill site, and dated the materials back to two thousand years before the present. One team conjectured that a group of hunters from a nearby village, carrying mussels from the river to ward off hunger, might have come across a small group of bison and herded them between two large sand dunes near the edge of the ridge. The hunters hurled darts with their atlatls, dispatching eight animals, then butchered them with heavy stone choppers and cooked part of the meat over a fire. When they departed, they left behind several stone tools and a pile of mussel shells.

In the centuries since that bison kill, the wind has continued to batter the ridge, sculpting shrubs and pitting rocks with airborne sand. Lowering my head into the relentless breeze, I reached The Otter’s broad back. Fractured escarpments along the spine of the ridge testified to the forces that folded and bent the mother rock back upon itself. The vegetation was low and open, a variety of tidy bunchgrasses offset by the deep olive of stiff sagebrush and the dusky rose bracts of summer hopsage. I passed a series of lichen-spotted cairns, marking out the long stretch of time during which the uplift has been both a spiritual and a practical landmark for a host of mid-Columbia tribes. For many generations, boys and girls of various bands have come to Nuk Say for spirit quests, and there are certain places on lower talus slopes where rocks have been carefully piled to create sheltered blinds, perfect spots to sit and watch for game.

The biting wind drove me back toward the swimmer’s midsection, where two lines of rock diverge to form an open cavity lined with grass. I settled into the protected nook and looked across the Columbia at the long curve of the White Bluffs rising steeply above the river. In the millennia since the last of the Pleistocene floods swept downstream, the river has steadily sliced a cross-section through its old floodplain, opening to view many pages of the basin’s history. As the river eats away at the bank, it occasionally reveals the antler of a false elk or the tooth of some long-extinct horse. Near the beginning of the bluffs lies a large island where modern horses, first acquired by the Wanapums through trade with tribes to the south, grazed in the shadow of their ancient ancestors.

The Spanish horses presaged the arrival of other newcomers. On a summer day in 1811, a cedar plank canoe flew through the rapids just upstream from The Otter, bringing the furman David Thompson, who stopped long enough to share a pipe and promise a trade house before sailing on downstream. But his description of the arid steppe and a note in his journal—“of course there can be no beaver”—made it clear that the desert held little real interest for furmen.

Aside from the fur brigades that paddled through twice a year, pausing only to camp and purchase fish for dinner, the Pasco Basin remained relatively quiet for another four decades. The pace of change suddenly quickened in 1858 with news of a gold strike on the upper Fraser River. Hundreds of men swarmed up the Columbia in canoes and skiffs; others came on foot or horseback, following a well-established Indian route from the Yakima River. Cattle drovers hooted thousands of cattle along the trail between The Otter’s rump and its flailing tail, then swam them across the river and headed north to British Columbia to feed the hungry miners. Campfires of sagebrush and greasewood dotted the flats at night. A Nez Perce chief rode to the White Bluffs with word of a skirmish on the prairies to the south, and Yakama warriors painted their faces in preparation for battle, but the Wanapum kept the peace, ferrying footsore miners across the river in dugout canoes in exchange for a handkerchief or a shirt or a fifty-cent piece.

The next year the sternwheeler Colonel Wright, named for the military man who was busy subduing the Plateau tribes, churned past to unload mining tools and provisions at the foot of Priest Rapids. An entrepreneur set up a ferry at the White Bluffs, powered by long sweeps; mule teams pulling freight wagons dashed past The Otter, then waited in line for three days or more for the ferry to transport them across the river to the dusty road leading north. Another steamer came on line, its giant paddle wheel pausing at a new dock beneath the White Bluffs while bags of gold dust were transferred from stagecoaches for the trip downriver. A storehouse, blacksmith shop, and saloon joined the ferry owner’s driftwood cabin on the wide beach beneath the bluffs.

As long as the goldfields held out, the sounds of wranglers and livestock filled the basin. The tribes began to complain of rising dust clouds and erosion, and exotic weeds like cheat grass and tumble mustard began to crop up on overgrazed terrain. In the village beside Coyote Rapids, just below Nuk Say’s tail, the Wanapum prophet Smohalla plaited strips of otter fur into his hair and performed the Dreamer dance. Smohalla beseeched his people to reclaim their spiritual heritage in the face of encroaching white civilization. If they could only hold true to the land, he said, the world would turn over and all that they had lost would come alive once again.

And then, as if his dream were coming true, the pack trains slowed and the cattle drives stopped. Save for a few Chinese miners who filtered in to pan for gold on the bars below Coyote Rapids, the crush of traffic ceased. Smohalla hoisted an American flag above his lodge and turned down the repeated entreaties of government agents to move his band to the reservation. A cattleman named Hank Gable began pasturing horses on one of the river’s grassy islands and running stock around the base of The Otter. Because it was the only prominent feature in the flat basin, early settlers identified the landmark with the rancher who worked it, and government surveyors inscribed the names of Gable Butte and Gable Mountain on their maps. One of them declared of the area, “a more dismal place it would be hard to imagine.”

But some people were taken with the stark beauty of the setting, and through the 1890s a few stalwart settlers trickled in, drawn by the long growing season and rich soil. Farmers took up land along the river between the ferry landing and the large Wanapum village at Coyote Rapids. The newcomers dug wells by hand and cleared sagebrush to plant melons, fruit trees, vegetables, and sugarcane. “Anything will grow if we can only get water,” they said. An eastern promoter enlisted investors and had begun digging a ditch to irrigate the land between the Rattlesnake Mountains and Gable Mountain when the financial panic of 1893 evaporated his capital. There was too much water in the spring of 1894, when a heavy runoff swept houses down the river along with livestock, furniture, and wagons. Those who stayed opened a school on the point of land below Gable Mountain’s shoulder and dug pieces of clay from the bluffs to use as chalk. A schoolteacher arrived, sunbonnet tight around her head, and watched her students assemble by horseback and rowboat. The aged Smohalla, blind and ill, mounted a horse and was led by his wife along the old trail beneath Nuk Say on his final trip to the Yakima Valley. Hank Gable purchased a new ferry upriver, floated it through Priest Rapids at high water, then hitched some of his horses to its newfangled treadmill.

Even though the Pasco Basin receives only six inches of rain a year, the dependable flow of the Columbia and a reputation for growing good fruit eventually began to lure homesteaders and speculators alike just after the turn of the century. A few miles beyond The Otter’s nose, the geometric lots of a new townsite were platted by Judge Hanford of Seattle, and dirt began flying from the ditches of his ambitious irrigation project. In the years between 1907 and 1909, promotional brochures advertised the area as the “California of the Northwest,” and steamers were crammed with settlers headed for White Bluffs and Hanford. More sagebrush was cleared, fields plowed, and orchards planted; more dust storms swirled across the basin.

In 1913 the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad pounded spikes into a spur line, inspiring the town of White Bluffs to move four miles west to meet the rails. For the next three decades the two small towns of Hanford and White Bluffs competed and socialized. Fourth of July parties were held on the ferry, and watermelons were cooled in the river in summer. During cold winters, children skated on the ice; in one particularly frigid year they were joined by two thousand sheep, a fraction of the twenty thousand that wintered between Gable Mountain and the river. Sahaptin youth still climbed Nuk Say for vision quests, and picnicking homesteaders scrambled to its summit to look down on their blossoming orchards and check the progress of a large substation being built just upstream to receive power lines from Grand Coulee Dam.

ON A CLEAR December day in 1942, a small plane bearing a colonel of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers flew in from the west, crossed the Pasco Basin, slowly circled the valley twice, then disappeared back over the Rattlesnake Hills. Two months later, an explosion of activity erupted around the post offices of White Bluffs and Hanford. Shocked residents held registered letters announcing that the United States government would be purchasing their property and over six hundred square miles of the surrounding countryside. They had thirty days to vacate their homes and farms. The purpose was top secret, a war effort originally called the Gable Project, later changed to the Hanford Engineering Works.

Within weeks, engineers carrying stakes crisscrossed the basin as people packed their belongings. Coffins were disinterred from cemeteries; trucks hauled furniture and livestock away. The Wanapum fishing villages near the White Bluffs were closed. Rows of barracks and Quonset huts quickly overran the Hanford townsite. Buses arrived daily from Pasco, bringing construction workers from all over the country. An access road was cut up the face of The Otter so that a radio tower could be installed on top; heavy transmission lines were strung across its back, and a hole was blasted in its side. Railroad tracks and dusty roads spiderwebbed the flats below. Between the landform and the river, enormous buildings began to rise from pits excavated into the deep sand and gravel left behind by the glacial floods. Fifty thousand workers swarmed around the buildings.

Early in 1945, the massive buildings were completed and the population tide at the construction camp turned: Loaded buses pulled out, and barracks were dismantled. Soon sand blew across the patios of the deserted trailer park as goats wandered the empty streets of Hanford Camp. Scientists continued to arrive, traveling under assumed names, and security grew tighter. Every so often during the spring and early summer, a caravan of three cars would emerge from one of the large buildings and proceed directly to the side of Gable Mountain. Two army officers carrying a small steel container would climb from the center car, approach a heavy steel door fitted into a short concrete wall, dial the combinations of two locks, and enter a vault carved into the base of the mountain. Minutes later, they would exit, swing the great door shut, and spin the locks. At regular intervals the process would be reversed, and a container would be removed from the vault and loaded back into the caravan.

On August 6, 1945, the Richland Villager issued a special edition headlined “It’s Atomic Bombs: President Truman Releases Secret of Hanford Product.” The vault beneath Gable Mountain, it turned out, had served as the temporary storage chamber for the enriched plutonium used to fuel the A-bomb that was built at Los Alamos, New Mexico, and dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

For the next four decades, throughout the grinding tensions of the Cold War, the Hanford area continued to live a secret life as new reactors were built along the curve of the river. By the late 1980s, however, all of the units had been shut down, and the focus shifted to nuclear power research complexes and decontamination laboratories. The Gable Mountain vault stored soil samples rather than plutonium. As attention increasingly turned to the accumulating deposits of radioactive material around the country, Hanford was named one of three locations to be considered as a national long-term disposal site. The Basalt Waste Isolation Project, or BWIP, envisioned repositories in stable basalt 2,500 feet below the surface, where spent fuel rods could be safely stored forever. Results from test wells drilled in the Pasco Basin during the Cold War held great promise—wildcatters had bored through 7,600 feet of basalt just east of the Columbia and struck crystalline basement rock; near Rattlesnake Mountain they had stretched the limits of their drill rigs through 10,660 feet of basalt without ever breaking through.

From the start of the BWIP project, geologists knew that many variables would have to be considered, and The Otter slithered back into the picture. A pair of hundred-foot adits were drilled into its western flank, then packed with geologic and hydrologic sensors. One of their major purposes was to learn how the heat given off by nuclear waste materials might affect the structure of the existing basalt formations near the river.

The Otter was not entirely cooperative. When snowmelt from the ridge began dripping onto the equipment in the adits, researchers realized that surface cracks penetrated surprisingly far into the bowels of the mountain. Deeper rocks turned out to be under more pressure than expected. Sensors recorded recent movement in the supposedly stable basalt. One fault had been generated by an earthquake estimated at 5.5 on the Richter scale that had occurred within the last two thousand years. To geologists with nuclear disposal on their minds, that was far too recent. In 1988, the stability of the rock became a moot point when the U.S. Congress selected Yucca Mountain, Nevada, as the approved disposal site. Authorities shut down the experiment on Gable Mountain and bulldozed the rubble into an approximation of its original form.

That shoulder of the mountain remains abandoned today, and the old plutonium storage vault is empty of everything, according to one Department of Energy official, except snakes and lizards. Within a couple of hundred yards up the steep slope, yellow and orange lichens begin to crawl again, and ancient stacked cairns seem to mark a defiant boundary: the big machines worked to this line and no farther. From here on up, The Otter prevails. Any stopping point along its ragged ridge still provides a breathtaking panoramic view of surrounding landmarks, old and new. The undulating profiles of Rattlesnake Mountain, Umtanum Ridge, Wahluke Slope, the Saddle Mountains, and the Horse Heaven Hills circle the horizon. To the north, neat rows of weatherbeaten locusts and Chinese elms outline the former streets of White Bluffs. Off the north side of Nuk Say, a skein of sand blows across the dunes where bison were butchered two thousand years ago. All around Hank Gable’s old grazing grounds lie the square concrete hulks of mothballed nuclear reactors. The White Bluffs, their mudstones and volcanic tuffs changing in color and texture throughout the course of the day, outline the river’s course. Eating steadily away at their layered past, one of the last free-flowing stretches of the Columbia, designated as the Hanford Reach National Monument, sweeps past. In the center of it all sits The Otter, still seeking protected status on the National Register in recognition of its cultural importance to native peoples and its pristine shrub-steppe communities.

The Hanford site is accustomed to handling the hot remains of a long cold war, and rectangular scrapes in the basin floor mark the burial sites of many decommissioned nuclear parts. In the summer of 1999, large machines clanked onto a special disposal area south of Gable Mountain and began digging a trench 850 feet long, 150 feet wide, and 45 feet deep to receive the reactor vessel of the Trojan Nuclear Plant. On the morning of August 19, with the hole finally finished, the tractor steered the trailer bearing that vessel to what was hoped would be its final resting place. Beside the massive ditch, U.S. Representative Doc Hastings gave a brief speech, then waved a small flag, signaling a drag-line operator to drop three yards of backfill onto the stubby hulk. Many of the people gathered for the ceremony were acutely aware that they stood on the brink of a pit whose effectiveness would be measured over epochs. Some spoke hopefully of the advances in disposal technology that might take place in a decade, or a century, or a millennium. But it was a scale of time that only The Otter, swimming above them all, could really comprehend.