One

I stood on the tarmac at the Kilimanjaro International Airport and was engulfed with the scent, the overpowering and unforgettable fragrance of Africa. I’d never before experienced anything like it. It was an amalgam of aromas in the steady breeze that had swept across the Serengeti Plain, skimmed across the blue waters of Lake Victoria, and filtered through the forests in the Kilimanjaro National Park. It drove off the acrid smell of jet fuel, replacing it with a blend of the fresh and pure—with a hint of the ancient and mysterious.

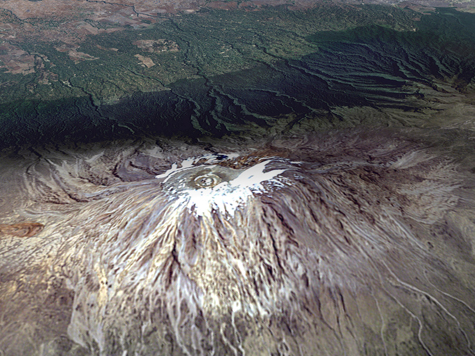

Here, in the middle of nowhere, with a commanding view of our destination—the summit of Kilimanjaro—the airport and its enormous asphalt strip seemed out of place. Billed as the “gateway to Africa’s wildlife heritage,” it routed tourists away from the grim desperation of the surrounding East African cities, but especially away from Dar es Salaam, on the coast, which had been the site of a truck bombing of the U.S. Embassy by al-Qaeda in 1998.

The sun overhead was bright this close to the equator, and my friend Tom Bauman gestured for us to move into the shade of the nearby terminal. From there I gazed back toward Air Force One, on which we’d arrived. It was one of two Boeing 747s used by the president. The plane was trimmed in blue and on the tail was an American flag with the number 2800. Near the nose was the Presidential Seal. United States of America was written long across the white of the side.

It was a handsome aircraft, and the long flight here had been very comfortable, indeed. There’d been some 70 passengers aboard, not counting the crew and Secret Service agents. Every seat was first class. Not bad at all. The forward section of the plane was known as the White House and was the presidential zone during the flight. I’d been invited up for a chat with the big man. I was hobnobbing with movers and shakers these days.

Accompanying us on the non-stop flight from outside Washington D. C. had been an airborne entourage of four other airplanes carrying cargo and more staff. Most of the president’s security detail, along with helicopters, motorcade vehicles and innumerable support staff and supplies of every kind, had arrived earlier and were pre-positioned both here and at the mountain. A traveling American president is a mobile, self-contained community. Some of the airplanes with us were still landing.

At least two perimeters of American security were about us. I could make out the closest one which included rooftop snipers, but the other was beyond view. The airport had been searched, inside and out, then searched again, and every person present today had been screened and scanned.

Calvin Seavers descended from Air Force One, spotted us, and walked over, carrying a small light blue carry-on bag. A medical doctor and author, he’d recently been appointed to the President’s Council for Fitness, Sports and Nutrition, and he’d spent most of the flight locked in conversation with the president’s personal doctor. Calvin was perhaps the world’s leading expert on high-altitude sickness and had just published his latest article on the subject. The president’s doctor, I understood, wanted his mind put at ease about the big man’s planned climb of Kilimanjaro and had requested Calvin’s presence. This was in addition to the traveling medical team that always accompanied the president.

So we were together at last, years after we’d first planned this climb. Climbing Kili together had first been discussed not long after we descended from Everest and the tragic events of that notorious climb, but it had been delayed repeatedly.1 Now it was a ‘go’—and in style.

“This reminds me of Kathmandu,” Calvin said as he reached us, as if he’d been reading my mind. Kathmandu had been the jumping-off point for our Everest expedition. We three had stood at the small airport there, wondering if the battered Russian helicopter to which we were about to consign our fates was airworthy. There was none of that on this trip. Everything was first-class, not just the cushy seats on Air Force One.

Tom was now about 40 years old, though as fit as when I’d first met him in Nepal. His prematurely gray hair was whiter than before but, if anything, gave him a more distinguished appearance.

Calvin was the oldest, likely in his 50s by now. Nearly six feet tall, he also had a robust physique, though he was trimmer than Tom. He wore silver-colored, wired-framed glasses, and his speech revealed his New England roots. He’d strolled across the tarmac effortlessly, but in the cold to come, up there near the Kilimanjaro summit, he’d likely limp because he missed the toes that were frozen off on Everest.

The Three Musketeers—back together again. Well, not the original three. Peer Borgen was gone, murdered on Everest, his frozen body 1aying up there for eternity. He’d bedded his last willing snow bunny, flashed his final grin, and would never again crack a joke. I felt a sudden ache for the hearty and brave man.

The scene around us reminded me of an anthill I’d stomped on once as a boy. This trip had been organized in record time, and it seemed to me that whatever the security guys may have lacked in their usual precision in long-range planning they were making up for with numbers and energy. I wondered what the locals made of it.

Anthony Salcito, head of the president’s Secret Service detail, came into view, the only one of them in a business suit. The other Secret Service agents were wearing various forms of tan Chinos and dark windbreakers. Their sunglasses looked regulation issued, and for all I knew, they were. Most, but not all, of the agents were men. They were fit—and very nervous. Despite all the rush to secure this trip and the climb, the reality was that dangers could well exist they’d not uncovered or encountered. This was a volatile part of the world, and this trip involved an enormous risk.

But the risk served an important political purpose, which, I believed, was the determining factor in its taking place at all. The president had never served in the military. Indeed, while a U.S. Senator he had been highly critical of America’s armed forces, but then, as president, he’d repeatedly placed them in harm’s way. While no one was using the derisive term “chicken hawk,” typically applied against gung-ho members of the opposition party who hadn’t served but wrapped themselves in the American flag, there had been insinuations of a lack of personal courage. Among all the other reasons given, I was persuaded that “image control” was one of the primary reasons we were here. The president needed to spruce up his macho image. Pickup basketball games can only carry you so far.

Salcito had flown on Air Force One with us and managed the smallish security detail attached to it. Of average height, he looked every bit an Italian and was in sound condition. Over his dark piercing eyes were bushy eyebrows. His teeth were even and bright. We’d chatted briefly both before and after takeoff, and I couldn’t escape the feeling that both occasions had been nothing more than an opportunity for him to size me up as a potential security risk. He’d smiled then—but wasn’t now. He had a forceful personality and was clearly not a man to cross. He might have been American born and raised, but he was all Italian.

In the distance, men were waving their hands above their heads as heavy black SUVs were slowly eased from the rear ramp of a C-130 cargo airplane. A short distance away I could see a helicopter emerging from another plane.

“Quite a show,” Tom said.

That it was.

“I wonder how anyone lives like this,” Calvin speculated.

“What do you mean?” Tom asked.

“Being the center of everything, the reason for all this technology and manpower. I suppose it can’t help but go to your head, which may explain a lot.”

“Maybe the office attracts those who want all of this,” Tom said.

Calvin nodded. “There’s that.”

I’d met with the president twice now and had a sense of what Calvin meant. The first time had been five months earlier, some weeks after I’d returned from climbing Vinson Massif2 in Antarctica. That expedition had taken place in the dead of winter, utilizing the very latest NASA and experimental U.S. military extreme cold weather gear. It had been set in motion and paid for by Robert Ainsworth, international arms dealer and all around nut job. We’d experienced equipment failures, sabotage, then outright murder. All but four of us who’d participated were dead.

My presence there had been on behalf of the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon’s CIA competitor, for whom I did the occasional favor. It had been phase two of an operation that had begun in the Andes Mountains. I’d been chasing three stolen Inca idols said to give the possessor supernatural and military power.3 Hugo Chavez had been after them, and the DIA didn’t want that to happen even if the legend was false. I’d succeeded in finally getting my hands on the savage beauties, but not before a river of blood had been shed by others in their pursuit. My confidential meeting with the president at Camp David had been to receive his congratulations and to be presented with a medal.

It had all been very pleasant and unexpected, though I don’t know exactly what you do with a medal you’re told not to show anyone or talk about. I’d been given the Intelligence Community Medal for Valor, or ICMV, which recognizes heroism and courage for what was said to be my contribution to national security. It was nice to be acknowledged, if a bit strange. In the unlikely event my presence at Camp David or of having received the medal ever came out, I’d been given a cover story to tell, one that related to my war experience in Afghanistan. Should I ever return to active military service, however, I’d be allowed to display it, since it would be taken that I’d acquired it in the performance of military operations.

Due to the large number of U.S. military personnel who performed duties under the authority of the National Intelligence Agency during the war on terrorism, a series of medals had been authorized. This was an effort to avoid the injustice that occurred during the Vietnam Conflict, when so many servicemen were assigned CIA duties. Many died while others served heroically, yet there was no official or public recognition of their sacrifice and service.

The president had spent a few minutes with me, expressing satisfaction with what I’d told him of the events in South America then Antarctica, giving me the full court press experienced politicians have honed to a fine edge. He was a handsome man, of half Irish-American and half African descent. Tall and trim, he’d flashed a “little boy” smile as he’d lit up a Menthol cigarette. “Don’t tell my wife if you run into her,” he’d said. He’d not asked permission to smoke, but it was his office, so I guess he didn’t have to.

The attention had been flattering, though I began to suspect that the extra minutes were designed to let him finish his smoke. He’d been friendly enough, if a bit reserved. I didn’t hold that against him. It wasn’t like we were best friends or anything. Still, I thought I understood just what Calvin meant. The president wouldn’t be as impressed with what we were seeing, and I doubted he had been after he’d been sworn into office.

Diana Maurasi emerged from Air Force One just then—looking, I must say, absolutely stunning. She’d worked her way up through the ranks of the Sodoc News Service, placing herself in danger repeatedly in so doing and after gaining a bit of fame had been rewarded with the role of evening anchor for three years. It had never been a good fit, in my view—or in that of the public, for that matter. First, she was too young to be taken seriously as the conveyer of bad news while she was, frankly, much too attractive. I’d once teased her that the suits had tried to turn her into a middle-aged matron in a futile attempt to give her the gravitas the job required.

The truth was, it played against her strength, which was the spontaneous field interview, the more dangerous the setting the better. Perky, sharp and smart as a tack, few could equal her in such a setting. And no matter how many times she “gotcha,” there was always some idiot who refused to take her seriously before it was too late.

The network had given her a morning show that had done pretty well, then the new president had snatched her up and named her his press secretary. I was no honest judge of how she was doing in the job; well enough, it seemed to me. She was more popular than the president, from what I read. My eyes, though, were no longer on her, but on the guy coming down the stairs behind her.

Christopher Hooker was a New York Times reporter and Diana’s current beau. Despite the unfortunate family name, he was handsome, with a full head of wavy hair, bright well-tended teeth and a hearty, even tan; Hollywood’s idea of a journalist. He was wearing a light colored suit without a tie. She turned to him and said something. He laughed.

I hated his guts.

Smiling, Calvin said, “Maybe he’ll trip and fall,” once again seeming to read my mind.

“I can only hope.”

I’d been carrying the torch for Diana ever since we’d met in Afghanistan, and though I’d thought she loved me as I loved her at one time, we’d never seemed to catch a break. Her career had kept her in New York, while mine was in the Massachusetts Berkshires working as a fellow for the Center for Middle Asian Studies. Now she was in Washington, D.C., while I was still traipsing around the world climbing mountains—too often for the Defense Intelligence Agency. It was time, I was beginning to think, for me to grow up. It was no wonder she preferred Mr. Good Teeth; I was still stuck with my own version of King of the Mountain.

Still, we’d never really ended it. Over the years, each period of separation had been followed by a time of rejoining, of renewal of what we’d found in Kabul, of all places. It was always magic—for both of us I was certain. But the truth was, she would not give up her career to join me, nor would I give up mine to be with her. So I guess I had it coming.

At the bottom of the stairs Hooker moved up beside her and slipped his arm around her waist, the jerk.

“Is he going on the climb?” Calvin asked.

“So I heard. He’ll be the rep for the media pool guys.”

“There’s some complaining about that,” Tom said. “Those not picked for the climb think he got a little help from Diana.”

“She wouldn’t do that,” I said, a bit indignantly.

Calvin and Tom looked at each other, then laughed.

Another 747 came to a stop some distance from Air Force One and was now disgorging its passengers. Even from this distance I could see Tarja Sodoc. Her blond hair flashed in the bright sunshine as she stepped lightly down the stairs. I could only shake my head in disbelief that she was here. A one-woman publicity hound, she was likely to draw more attention than the president.

In a sane world, she wouldn’t have been part of this traveling roadshow. But her life had taken a few odd turns, to put it lightly. After marrying Derek Sodoc, only son of one of the world’s richest men and heir to his father’s vast world-wide media empire, Global News, she became a widow on Everest just a few months later. Derek’s father, Michael, died violently the following year, and his widow, the Russian ex-model named Natasha, had settled Tarja’s claim to her husband’s fortune rather than go to court as dueling widows dressed in black. Tarja had purportedly received a hundred million dollars for bowing out.

You’d think that would have been enough, and though Tarja was always about more than money, money was very important. She’d paid her taxes, flown here, flown there, been seen with rich playboys and movie stars. At one point a sex tape of her with a Saudi prince had been leaked, a la Paris Hilton, and the bright light of fame she so eagerly sought shone on her for a few heady months. In short, she was living her life as she wanted when the real estate collapse hit. It turned out that she’d invested heavily in overpriced stuff. I’d read she was down to her last few million.

Tarja stood at the bottom of the stairs and waited on the old guy trying to bound down them like a chipper youth. Dressed in tailored Abercrombie & Fitch dust-colored Safari clothes, Aleister Cavendish was her latest conquest. He was at least 70 though tanned and tucked, he looked younger. Widowed the previous year, he was the president’s most effective single donation machine. He didn’t just bundle contributions, his company had come up with a system that milked the public cow for every drop of campaign money.

He’d also served as the president’s Senior Advisor for Domestic Affairs until the previous fall, when he’d stepped down to work on the re-election campaign. He was heading up a Super PAC with the expressed objective of steamrollering the electorate come November. If he’d been indispensable in letting the president all but buy his first election, running neck and neck in the polls as he was, Cavendish was even more essential this time out. No one doubted that he remained the man’s primary campaign advisor. And if he wanted to bring his hottie mistress along, with all her enormous baggage, then that was just dandy.

“Let’s go inside,” Tom suggested. We turned and entered the terminal. It was a long, flat building with a russet colored roof. Inside was new and clean, and much too small for all those who’d soon be off-loaded from the taxpayer-supported fleet that had just arrived.

“Where’s Natasha?” Calvin asked.

Natasha Sodoc, widow of Michael, was to join Tom here. As usual, she was mixing business with pleasure. Her world news service had media holdings in Africa, and she was here to expand them, so I’d read.

“She’s due in later. She’s at Dar es Salaam, on the coast, meeting with business types. We’ll be flying on to South Africa after the climb, then to Egypt. She’s got some new African news service she’s introducing.”

“She’s not climbing, is she?” Calvin asked.

“Natasha? Not hardly. No, during the climb she’s staying at a five star Kilimanjaro resort and will do the national parks tour. Officially there was no room at the inn here, and she’ll be pampered there, but I imagine it’s got more to do with this wiretapping scandal she’s been pulled into. Regardless, she’s looking forward to her Serengeti safari.”

“Just so she doesn’t get eaten by a lion,” Calvin said.

“I’m more concerned for them than I am for her.”

Just then Diana swept into the waiting area. Spotting me, she smiled warmly, and came over with Hooker tagging along. I wondered for a moment if he’d like to join Natasha on her safari. I could put in a word. She owed me a favor or two, and who was to tell?

“Scott,” Diana said, then took me into her arms and gave me a lingering kiss like long-lost lovers. I hoped it gave Hooker heartburn. “I heard you were coming. I’m so proud of you. When we have time, tell me about Antarctica. The president was very impressed when he heard the story.”

“Sure. When you can.”

“Hi there,” her companion said, edging Diana a bit out of the way. “I’m Christopher Hooker. I don’t believe we’ve met.”

I did the expected. I noticed that he ignored Tom and Calvin. I guess he didn’t need them just then.

“Look, I’ve got to go,” Diana said. “I have to make a statement to the local media, then we’re all moving to the lodge. I’ll be juggling a lot of balls once there, but maybe we can meet for a drink tonight once things quiet down.”

“We’ve got that…thing,” Hooker said.

Diana looked at him as if suddenly remembering he was there. “You go ahead. I need to catch up with Scott.”

Hooker grinned, but I spotted something churning behind his glowing, blue eyes. He knew competition when he saw it. “Sure thing. Nothing like old friends.” He remained doggedly in place. Diana smiled again, then waved to us all as she walked toward the front doors. Just outside stood the cameras and an eager pack of international and local reporters.

Tom looked at Calvin then said, “I can tell we’re in for a very good time.”

1 See Murder on Everest.

2 See Murder on Vinson Massif.

3 See Murder on Aconcagua.