Five

The vans and SUVs pulled away from the lodge shortly after breakfast the next morning. Onesphory’s home village, Tumbu, was less than an hour away.

In fact, most of those who’d come on this trip, not counting security, were not even going up Kilimanjaro. A number of White House and other administration officials planned to visit the nearby parks and take in a Serengeti safari. For them, this was just a paid government holiday. And of those who would trek, nearly all planned to remain at one of the lower camps rather than attempt the summit.

Our caravan drove toward the town of Moshi along a two-lane paved road, passing through a succession of villages, each announced by speed bumps that slowed us to a crawl. Despite the primitive appearance of these settlements—at least as compared to Europe or North America—and the thick vegetation between them giving a rural impression, the region surrounding the base of Kilimanjaro was heavily populated. These numbers placed an excessive strain on the ecology of the area. Illegal wood gathering and charcoal making were slowly deforesting the region, which, if not stopped, would render it a new and equally desolate Haiti.

Security was out in force, as this visit had been made public. It was, in fact, a set piece of the trip. Tanzanian military and police were in each village, armed uniformed men standing listlessly beside four-wheel-drive vehicles.

Our caravan traveled in a cocoon, swathed in Secret Service agents. All along the way brightly dressed villagers turned out in force to see the return of Kubwa Moja, meaning The Great One, the local name for the president and of his son, Onesphory. As we drove past they applauded, grins on their faces.

In the van with me were two stoic Secret Service agents, one driving, one riding shotgun. Beside me was Calvin, while in the back seat sat Rajabu Msingi, our principle guide and native of Tumbu. With him was Tom, whom I’d persuaded to join us over breakfast.

“This is really something,” Tom said as we crawled through the fourth or fifth village, the crowd breaking into song. “I’ve never been in a procession before. Pretty heady stuff.”

“A bit of the presidential luster rubs off on us, I suppose,” I said.

Tom leaned forward. “I was talking to someone on the flight over. This is going to be very interesting today.”

“How’s that?” Calvin asked, turning slightly in his seat to make eye contact.

“For one, the chief and Opie’s mom had a son the year after he was born—named Itosi. Until recently he’s been the second son, with no special future. Now it turns out he’s actually the chief’s sole son, the only one of his blood, and in the Chagga culture that is very, very important. This is a patriarchy, after all.”

“I read that Onesphory is popular in his village,” Calvin said.

“Me, too,” Tom said. “And I think that’s creating a problem. There are two camps now about who should take over when the time comes.”

“Chagga chiefs don’t do all that much these days, do they?” Calvin said.

“I’m not sure,” Tom allowed, “but it’s a high honor, a prize worth getting. I think they have a say in the disbursement of funds, things like that, so there’s real value in being chief.”

“Is that right, Msingi?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, every man want to be chief but it usually go to the oldest son.”

“Who’s the oldest son now?” I said. Msingi didn’t answer. He just grinned, then laughed.

“There’s more,” Tom said. “Onesphory’s mom is pretty young, I heard.” He left it there as we absorbed the significance.

Finally, I said, “How young?”

“Well, the guy I talked to is really concerned about it. It turns out that Mbalule was 16 years old when the president made his visit. You know those reports about that prestigious school she was attending and home from vacation from? It was a high school. She’s just 36 right now.”

“Is that right, Msingi?” I asked.

“Oh, yes. Chief’s wife is very handsome woman.” Msingi was a smiling, seemingly happy man. He was dressed in worn khaki shorts and shirt. He wore a floppy hat and sunglasses. The rest of us were in tan chinos and casual shirts. I’d brought along sunglasses and the official cap they’d given us on Air Force Ones. The cap, we’d been told, was impervious to the sun.

“How are they going to handle this?” Calvin asked.

“As I understand it, the age is perfectly acceptable in Tanzania,” Tom said. “Women often marry at 16 and younger, though it is not as common today as it was then. Is that true, Msingi?”

“Yes, 16 is not so young. My wife was 17 when we married. I was 18. It is good to have a wife while you are young. It keeps you away from bad woman—usually.” He grinned.

“You’re right,” I said, “this might be very interesting, indeed.”

Tom continued, “I understand the media pool has been carefully selected. Just two reporters and two photographers.”

“Still,” Calvin said, “won’t it depend on how young she looks? Though I suppose that it’s bound to raise unpleasant questions.” We drove in silence for a time then Calvin added, “Maybe that’s the real reason the First Lady didn’t come.”

I wouldn’t swear to it, but it seemed to me a brief smile crossed the lips of the Secret Service agent in the passenger seat as he exchanged a glance with the driver.

Half an hour out, we turned onto a red dirt road and headed to Tumbu. As I understood it, there were some 18 significant forest villages and any number of smaller settlements ringing Kilimanjaro. The major villages situated on the north and south slopes of the mountain were oriented toward the heavy tourist trade that was a bigger business than actual mountaineering. Those on the others sides were more remote, often reached by foot and less disturbed by the rampant tourism that had all but destroyed traditional village and Chagga tribal life elsewhere.

Kilimanjaro is one of the largest volcanoes on earth, and as often is the case, the land about it is very fertile. It produces crops of bananas, potatoes, onions, tomatoes. Coffee plants were placed beneath the banana trees for shelter from the bright sun. Every village we passed had a supply of goats, as well as a few cattle. And while I saw no signs of starvation or evidence of malnutrition, I saw no indications of affluence, either. It was a hardscrabble life.

The area surrounding the mountain was one of the oldest inhabited areas on earth. Fossil remains dating back two million years have been discovered here. The current occupants were Bantu speakers and had begun migrating into the region about 2,000 years ago. They were followed by a series of migrations of Nilotic people from the upper Nile region. These groups spoke a different language and had a distinctly different appearance.

The settlers began to produce high quality steel and iron soon after they arrived, and this caused Arab traders to establish trading settlements along the coast. But the primary commodity for trade evolved into slaves. More than 700,000 slaves are known to have been exported from the coast in the 19th century alone, with an equal number taken from the interior and held in bondage.

The local tribe around Kilimanjaro was the Chagga, one of the largest ethnic groups in Tanzania. It had moved into this region relatively late, some 300 years earlier, and had violently displaced the people already here. While the Chagga are Bantu speakers, they do not use a single language, but rather a number of dialects. These dialects are related to those spoken in northeast Kenya and to other languages spoken in the east, regions with which they maintain close cultural ties. They follow a patrilineal system of descent and inheritance. Swahili, originally the language of traders, was the common language throughout the region and, indeed, across East Africa. It had originated as a Bantu dialect, but over the centuries it adopted many words from the Arabs, Westerners and more common dialects.

During the 17th and 18th centuries the Chagga were organized into a great many villages which were situated along highland ridges. They circumcised boys and initiated them in rituals typical of ancient Bantu practice. But they also practiced female clitoridectomy.

The Chagga people have their own lifestyle, which differs from that of the other tribes found in Tanzania. One notable ceremony takes place during the month of December, when the Chagga people gather from wherever they have been working and travel to their motherland and home village to celebrate. Sacrifices and rituals are performed at this time to venerate and remember their ancestors.

Lacking any central control, the Chagga area was originally divided into a number of chiefdoms, every one of which lived in a constant state of war with at least one other. Warfare consisted of raids for slaves and cattle. Pitched battles were rare. Trading these captured slaves to the coastal region was their primary industry. Over time, the number of chiefdoms was reduced to six, but by then, in the late 19th century, the Germans had come. The presence of outsiders served to unite the Chagga into the single tribe that now existed.

Though Europeans explored the region, it wasn’t until 1885 that Germany took possession of the territory, soon creating a colony known as German East Africa. It was short-lived, as they lost the colony with the end of World War I in 1918. But while they were there the Germans introduced Christianity and abolished the brutal practice of female circumcision. They introduced coffee and rubber trees to the region and created an infrastructure. Gold mining was significant, but despite their efforts, that industry was never profitable.

In general, the German colonization had been relatively benign, but the cities and railroads they’d built, as well as the cash crops they’d introduced, all improved the quality of life. Trade with Europe and the higher level of education among the governing class made this the richest area in Africa. And because of their particular brand of Christianity, many of the tribe had unique names.

The major industry was now tourism, though it had the undesirable consequence of warping life in the villages dramatically. Eco-tourists and trekkers were well-to-do, and the local people had become accustomed to sticking out their hands for a handout, figuratively and literally, which had the effect of turning most of the people a Westerner encountered into actors in their own life. The more tourists came seeking the “real Africa,” the more the natives made certain they’d see a dog and pony show.

From our motorcade I’d witnessed any number of youngsters run the roadside, shouting for candy and money. And for good reason, because I also saw candy, coins and bills being pitched out the windows of the vans. Bad idea.

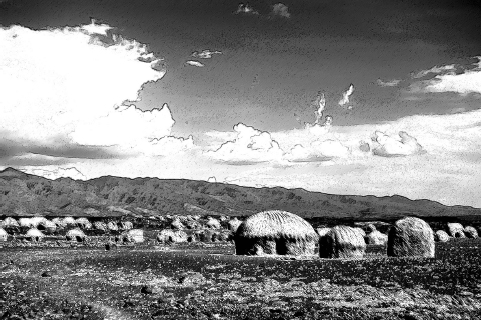

The traditional Chagga house was thatched and constructed much like a beehive. A few examples were displayed for the tourists in some of the villages, I’d read, but the houses now were mud brick with thatched roofs, or, in some cases, made from rusty sheet metal.

About one hour after we left, security along our route noticeably increased. They had this place sealed as best they could. The caravan slowed, then, a few minutes later, pulled into a village I took to be Tumbu, Onesphory’s home and that of his mother, the president’s former teenage lover.

Even as we approached the village, people were lining the road—waving, beaming from ear to ear, shouting out, or singing. The crowd grew in intensity and depth as we entered the village itself, and our vehicles slowed to a crawl. At the village center stood a great throng, perhaps 5,000 in all. The party atmosphere permeated the smoke-colored glass of the van. There were joyful songs, cheering, waved colorful kerchiefs.

Tanzanian military were everywhere, forming long lines that attempted to control the assembled joyful mass. As I understood it, for some days the local police, to keep the numbers manageable, had been preventing anyone from entering Tumbu who did not live here. Still, it seemed that every resident from throughout the country and even some from abroad had come for the occasion, and for all that effort the village center was filled to overflow.

They were dressed in their Sunday best. The Chaggas are devout Christians, so many of the men were decked out in dark, western-style suits, while a number of the women would have been comfortable attending any African-American protestant church in America, even to clutching small purses before them. The majority, however, were dressed in various forms of traditional attire consisting, in the case of the women, of very bright, multicolored garments bound with scarves or thick belts about the waist.

For a moment the vehicles all but stopped before cautiously nosing forward. The SUVs carrying security peeled away from the rest and drew up in an inconspicuous, irregular ring while the other vehicles came to a stop in a single line just within the central marketplace.

The agent in the passenger seat turned toward us and said “Wait,” as he climbed out. Secret Service agents were spilling out of vehicles all about us, every one of them wearing sunglasses, their right arms held close to their sides, pressing beneath their blue bulletproof windbreakers the automatic weapon each carried. It was likely the small but deadly FN P90. Their sidearm was the SIG Sauer P229.

Tumbu was a smaller version of the many villages we’d passed through. There was a nearby church, a store of the same size, and a school. Each of them—and the houses facing the market—had all been freshly painted. There were no paved streets, but the dirt was beaten down hard by the generations who’d lived here. Beyond this circle the houses were not close together, leaving a bit of greenery between them, enough for an extensive garden and a measure of privacy. Those areas were now filled to overflow with gaping locals who’d trampled the gardens flat.

There was electricity but no plumbing. As I say, a hardscrabble—though not unpleasant—life. Despite the village’s backward appearance, it was well tended. I knew it was served daily by a mini-bus system, so the residents were not cut off.

The agent rapped on the sliding door and through it told us we were good to go. As I stepped outside, the sun was piercing in its intensity, and I slipped on both my sunglasses and my new cap.

The reporters clustered beside the third vehicle back, the SUV that—it turned out—had carried the president, Onesphory, and his two friends. The young men were neatly and casually dressed, while the president wore a blazer, a blue shirt without tie, and gray slacks. He smiled broadly and raised both hands above his head in the style of a campaigning politician.

I looked about and watched as the Secret Service agents, some of whom had been pre-positioned, formed a nearby ring. Some of them I could tell were within the crowd itself, dressed casually, African-Americans who still stuck out noticeably.

Nearby was an assembled troupe of women, young and middle aged, identically clad in leopard-pattern dresses with white scarves around their waists and bright beads circling their necks. Two of the women held drums, and as I watched, the beating began and the others broke into a traditional dance of greeting. This consisted of a bit of jumping in place then swaying left and right in unison. The immediate crowd clapped in rhythm and joined in song.

Onesphory was beaming with pride, all but bursting, while his father smiled broadly in obvious pleasure. Brendan and Ian stood beside their friend and slightly back, clapping hands in rhythm with the beat, grinning at the scene in genuine pleasure.

The locals were a handsome people, tall and slender for the most part, with dark skin and fine features. Among them I spotted a number of young women, some not much more than girls, with close cropped hair, carrying themselves proudly erect, each wearing a delicate, silky garment that accentuated her every feminine feature. A few caught my gaze and met my eye forthrightly.

When the women finished, a group of younger women moved into where they’d been, their arms interlocked, swaying back and forth to the steady beat of a different kind of wooden drum. They wore matching long dark skirts and white blouses. The drum’s pace increased slightly, and now the women began to kick forward with one foot, bouncing lightly on the other. They worked by watching each other, and shortly they were in synch.

The crowd loved the show and clapped to the drum beat. The president was grinning, and the reporters were snapping photographs and filming, while Hooker stood just beside them, looking on intensely, as if witnessing a historic event.

As the young women finished their dance and moved to the side a group of men came out single-file, bracing on their left shoulders an enormously long, narrow drum that was apparently carved from a single log. They wore dark trousers and nearly-matching red T-shirts. With their right hands they beat on the mouth of the drum, which sounded much like an Australian aboriginal didgeridoo than anything we’d heard up to now. They sang in parts. This was a performance rather than a dance, but it was no less enjoyable.

After a few minutes another set of dancers came on. These were colorfully dressed men, some wearing a traditional tribal headdress, the leader’s expansive one resembling a lion’s mane. He was much older than the others. He called out a chant and the men responded in unison to the beating that sounded as if it came from a western snare drum. They were in fine voice.

The tempo increased, and the chorus began a synchronized movement, back and forth. They dipped slightly, then with increasing measure until finally they were touching the ground with one hand, bringing it up sharply, only to bend again at the waist and touch the ground again. All the while the old man called out and the young men responded in unison. Their deep, masculine singing, coming in reply to the leader’s chant, was the most African experience I’d had since arriving.

I was prepared for these men to go on all day, but after a bit they faded away and there, as if by magic, stood Onesphory. I’d missed the moment when he’d slipped away. Now he’d returned, dressed in tribal attire entirely, his young, trim body nearly naked. About his waist was a meager cloth. Colorful fastenings were about his ankles, and he wore one of those lion mane headdresses. He carried a stick much like a spear, and to the rhythm of a drum he began to dance what was clearly a welcome to his father. I saw two Secret Service agents ease closer to the president, their eyes intent on the stick.

The crowd was enraptured with the dance and clapped in joyous rhythm with the beating drums. From time to time a woman called out in that piercing trill I usually associated with Arabs. The drums I had taken for snares were beating, joined by a deep bass one, backed by the steady intoning of the narrow log drums.

Onesphory danced with natural grace and dexterity. He leaped in the air, spun, knelt, then backed away, rushed forward, moving first to one side, then to the other, all in harmony with the beat and the calling of the women. Sweat now beaded his body. His eyes looked at his father, as if in worship. He was breathing hard. The dance continued for some minutes then, after a powerful series of leaps, he rushed toward his father and, in a highly symbolic gesture, dropped to one knee, his long arms extended before him, holding the staff—which he now lay on the ground as if in offering.

Only in the sudden silence did I realize how loud the beating had become. I glanced at Brendan and Ian. Their eyes were round. Ian was biting his lower lip. They both appeared overwhelmed by the experience, and I had to admit that there had been something surreal about the entire dance.

The president didn’t know how to respond for a moment. Then, breathing rapidly to catch his breath, Onesphory spoke. I couldn’t hear what he said. Next, the young man reached down and picked up the staff, which he brandished over his head as he spun in place. The crowd roared its approval.

Onesphory was shiny with sweat as he stepped beside his father. Village elders, both men and women, now approached, carrying traditional gifts above their heads. Each addressed the president singly, said a few words in Swahili—which Onesphory translated—then laid the offerings at the president’s feet. This went on for some minutes until perhaps 20 gifts had been piled there. Then a profound silence ensued.

Onesphory tugged at his father’s sleeve and directed him toward the chief’s home. The crowd respectfully cleared a path of honor as the two advanced, closely followed by Ian and Brendan and two discreet Secret Service agents.

The chief’s house was a bit larger than the others, of course, but not noticeably more luxurious. Diana now appeared not far from the president, and beside her was Hooker, his cameraman hugging his shoulder. There were official cameramen, as well, from the Tanzanian government recording the epic event. Everyone in the center of the storm was looking at ease, even the young men who were taking their lead from the president, but all about them and beyond was a joyful frenzy.

Standing at the front door to greet the president was a man of great dignity, wearing traditional dress, a grounded staff in his right hand. He stood rigidly erect, and I estimated that he was nearly as tall as the president, just over six feet. This was Freeman Kleruu, Onesphory’s stepfather and, until a few months before, his putative father.

To his right was a young man wearing a carefully neutral expression. He stood rigidly, like a statue. This would be Itosi, the chief’s son. There was something in his eyes that I studied.

Hate. A deep, profound, utter hate.

On the other side of Kleruu was a stunningly beautiful woman. One glance at her and I knew the White House wishes were in vain. Onesphory’s mother might be 36 years old, but she didn’t look a day over 24. She was more believable as the young man’s girlfriend than as his mother. She was tall and trim but with the more complete—and desirable—figure of a grown woman.

Her features were delicate and well formed. Her alert eyes were deep set, a soft, enigmatic black in color, and when she smiled she flashed perhaps the most becoming smile I’ve ever seen. It was rich with intelligence and welcome, but there was also another aspect, a deeply sensuous element. Any man, anywhere, anytime, would be putty in this woman’s hands.

This was, I knew, a state event of a kind. The security and media presence made that obvious. It was also a family reunion, while for Onesphory it was a homecoming. It was, as well, the return of Kubwa Moja to his father’s village, the place where he’d spent a single significant month 19 years before.

But as I watched Kleruu greet the president with a slight bow then extend his hand, as I saw Mbalule embrace her son, and as the entire group filed into the dwelling for private time together, I couldn’t help but notice the look in the chief’s eyes or the unconsciously wary expression on the face of the president.

We three strolled about the village during the sit down, the crowd respectfully giving way, a throng trailing us, as one followed everyone who’d arrived with the president. The usual marketplace was taken up with the vehicles, but enterprising men and women had set up just down the streets leading away. On display was a wide assortment of local items, including an abundance of local fruits and vegetables. There were stacks of bananas galore. Tom, Calvin and I examined the craft items, and I couldn’t help wonder how many originated in Tumbu and how many were actually traditional. Most of the carvings looked like something I could pick up back home at a shopping mall import store. Of course, back there I couldn’t brag about buying it in Africa.

After a few minutes, those tailing us lost interest in watching three men shop—though the crowd only thinned, it didn’t go away entirely. I couldn’t help notice that a number of the lithe young women who remained were extremely open in their manner, almost inviting. For all the racism the West is accused of, I understood that white skin here was considered very appealing. At least that’s what I attributed the interest to.

Msingi approached us out of the crowd. “My house is here,” he said, smiling and gesturing up the narrow street. “Meet my family and have tea. It is hot in the sun.” It wasn’t exactly hot, given our altitude, but with the intensity of the sun’s rays, I was grateful for the invitation. We ducked into his house, where we were greeted by his plump wife and three young daughters. Msingi made introductions. Everyone smiled and nodded. Then he gave orders in Swahili and his family vanished into another room.

We took our places and removed our caps. “This is quite a turnout,” Tom said. The room was of modest size, with a hard floor.

The furniture was made of a blond-colored wood and had every appearance of being locally constructed.

“Oh, yes,” Msingi answered, “we are very proud to have the President of the United States in our little village. Everyone has talked about it for weeks now.”

“Onesphory seems happy to be home,” Calvin said.

Msingi laughed. “That one. I remember him as a boy. He was very mischievous, but the young sons of chiefs are often that way, I am told. Mangi are like that when they are little.”

“Mangi?” I repeated.

“Our word for chief.”

His wife and daughters returned bearing trays with cups, sugar, canned milk, a pot of tea, and sweets. They set them down, then his wife poured us each a cup of hot tea. Msingi gestured for us to eat.

“You have climbed Kilimanjaro many times?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, very many times. I was first a porter when I was 16 years old. For many years I climbed the mountain eight or ten times a year. Very busy.”

“Have you summited?”

“Oh, yes, when I was 17 the first time, many times since. But this will be a very special climb. I am honored to be chosen.”

“How did that happen?” Tom asked.

Msingi grinned. “Onesphory is my nephew, the chief is my brother. Onesphory wanted me.” Then he laughed.

We drank the very pleasant tea and ate the snacks, which included the English cookies they call biscuits. The well-scrubbed girls in their neat dresses sat to the side, a bit in awe of these white visitors, while Msingi’s wife stood beside him, politely listening but never speaking.

“You want beer?” Msingi asked. “It is very good. Made here from bananas.”

We assented and each took a large glass of the local brew, called mbege. It is made of millet and bananas and fermented in just ten days. The first sip was a little bitter, but that faded with the second, leaving behind a pleasant crisp, yeasty sensation. Not bad at all.

“You like?”

We three nodded and drank heartily, the stuff going quickly to my head the way an unusual alcoholic drink will do.

“Did you know the president’s father?” Calvin asked.

His name had been Godlizen and he was, by all accounts, a flamboyant man. The name, not uncommon among the Chagga, was a colloquialized version of “God lives in me.” He’d been bright and obtained a scholarship to study overseas. He’d attended USC in California, then transferred to college in Hawaii. It was there he’d met and soon made pregnant the very much younger freshman mother of the president. There were mixed reports about whether or not a marriage had taken place or, if it had, whether it was legal, since it turned out that Godlizen already had a wife in Tanzania.

Regardless, the pair had not stayed together much after the president’s suspect birth. There was a birth certificate which certain groups claimed was a forgery. The entire affair had been sensationalized by the refusal of the Hawaiian equivalent to Department of Vital Statistics to simply release a birth certificate. Any reporter from anywhere could get one for anyone, except the president. It was all very strange.

“Godlizen was my uncle,” Msingi said. “I knew him as a boy.”

I had to think about that a moment. “So Freeman and Godlizen are brothers, is that right?” asked.

“Half-brothers, yes.”

“So Freeman is actually the president’s uncle,” Calvin said.

“Oh, yes. We are all related in this village.”

“So what was Godlizen like?” Tom asked.

“A funny man, a trickster, you know? He liked to get people to do things. I heard he did that even when he was very young. Very funny man. I liked him very much.”

“How did he die?” Calvin asked. “I’ve read different reports.”

“He came back after school and worked for the government, but an election changed things and he lost his job. He was here when it happened.”

“When what happened?” Tom asked.

“When a lion ate him.”

That brought the conversation to a halt. Msingi took the time to refill all our glasses. When we resumed, Calvin spoke. “I don’t mean to be out of line, but did the village know that the chief was not really Onesphory’s father? In my experience a place like this has few real secrets.”

Msingi turned serious. “It is no problem to ask. There was talk among the old women, yes, but it was not mentioned by others. Freeman and Mbalule were married for some time; the baby came early.” He grinned again. “That is not so unusual.” He glanced toward his oldest daughter, who did not understand his meaning. His wife blushed.

“It must have been a great surprise to learn that Onesphory’s real father was the president,” Tom said.

“Oh, yes, for me a great surprise when I first heard.”

“What about Onesphory’s brother, Itosi?” Tom asked. “What’s he like?”

Msingi smiled. “He is a quiet boy. It is our custom for the second son to keep his place. He was treated like any other boy in the village. He has been very surprised by what has happened. You know how families are, keeping secrets away from those most influenced by them.”

“So Itosi had no idea about his older brother’s real father?”

“I don’t think so. It was women talk when they wash clothes.”

“What is he like?”

“Onesphory would always be chief, so he gets everything first, you understand? I think it is like that everywhere. Itosi got old clothes; sometimes they did not fit. He looked very funny, and children laughed at him. But that is the way with second sons; only the first gets new and the best. Onesphory is very smart, very friendly, very popular. Itosi was looked down on; very unfair, but that is how things are in a village like this.”

“His life has certainly changed.”

“Oh, yes, very much. People smile now when they see him. No one laughs anymore.”

“So he’ll be chief?”

Msingi smiled as if embarrassed. “Who can say? There are those who want him to be chief, others who want Onesphory. Now that Onesphory has brought Kubwa Moja here, people see what he can do. America is very rich. Kubwa Moja can do good things for us, and if his son is chief, or will be someday, then he will do them. That is what people say.”

He poured more banana beer, and we all become a bit more than mildly intoxicated. We asked about Kili, and Msingi told us of his many climbs, some funny stories, too. In time the conversation turned back to the village.

“We are happy to have Kubwa Moja return home. He has been gone too long.”

“He must have made quite an impression when he visited before,” Tom said.

“Oh, yes, but you must always come home, no matter how great you become. It is our custom, our way. Otherwise you lose yourself. The place where you are born is sacred to us all.”

I was confused. “You mean Onesphory?”

“Oh, yes, and Kubwa Moja, too.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t understand.”

“No problem,” Msingi said. “I will show you.” He stood up and gestured for us to go outside. There, in the bright sun, he pointed to the chief’s house. “Onesphory born there.” Then he pointed up the street toward a house very like his. “Kubwa Moja born there.”