Seven

The next morning we moved out with all the precision of a military operation, headed for Machame Gate, the entrance to the park and the place from where the climb would begin. I’d made a mental count and concluded there would be approximately eight climbers intending to summit on this expedition. I did not include Stern and Fowl, nor did I count Diana, who’d already told me she’d be stopping at one of the lower camps, nor Martin, who I couldn’t see going up all that far. But there’d also be at least a dozen Secret Service agents plus, inevitably, Hooker, along to cover the climb for the media. None of this included porters and guides. There’d be three of them for each of us, though just one would actually climb beside us on summit day. The other two would be carrying what we needed and would set up and take down each campsite.

Finally, there was the five-man medical team. It carried all of its necessary gear and were prepared for most any emergency. A helicopter could access nearly every place on the mountain so their job would be limited to treating the president’s ailments or keeping him alive until he could be quickly transported for the finest medical treatment available. I didn’t know how many of them would join us on summit day but doubted it would be all of them, and most of their fancy equipment would have to be left at High Camp. All in all, a fairly large expedition, though not unmanageable.

An exact count would have to wait for summit day, as somewhere between this enthusiastic “now” and the inevitable “then” well intentioned climbers would, for one reason or another, decide against or be compelled by illness or injury from making the effort. The easy stages, much publicized, slowly took their toll on climbers, who soon developed blisters, twisted joints, strained backs, suffered from the altitude, and fell sick. In fact, sickness was one of the most common features of this climb.

Our caravan was comprised of eight black SUVs, followed by a trail of vans. The president was in one of the SUVs, but I had no idea which. Our gear had gone up ahead of us and would be waiting at the park entrance, along with the porters and guides. It was a short half-hour drive to the Machame entrance.

The Secret Service had been at security arrangements for this jaunt for at least two weeks. Every possible spot for an ambush had been identified. In some cases, it had been cleared of boulders or trees that would provide an attacker cover, otherwise the location was today occupied by agents. I saw the counter-snipers in place, as before, and the Boomerang. Overhead, the trio of Blackhawks circled like fast-moving vultures.

The natural bush and lowland forest of the rich volcanic land surrounding the mountain had been replaced by cultivated fields and pasturage. They grew maize, sweet potatoes, yams, beans, peas, red millet and bananas—lots of bananas. I could see the trees everywhere.

Large wild animals which had once been common to this area were now rare, though birds, monkeys and smaller creatures were abundant. And the carnivores had not been entirely eliminated, since we were so close to the Serengeti where they still thrived. Goats, for one, were routinely taken by lions.

The Chagga eat no fish or poultry, as the former is considered unhealthy and the latter unmanly—being so tender. Goat is very popular, and the ones I’d seen were diminutive and handsome, with small horns. The Chagga diet is predominantly meat and milk, plus many vegetables.

As we neared the entrance, which is at 6,800 feet, we entered a cloud bank or mist and the road turned to red dirt then to mud. The large trees and thick brush were heavy with dew. I wondered for a moment if someone had miscalculated. This climb was supposed to be over before the very predictable rainy season arrived.

The caravan slowed, stopped, then moved forward at a much slower pace as we passed through the teepee-shaped gate. Beside it on each side were offices for the park rangers—sambas, as they were known. Around it and nearby were vendors hawking their wares, which included everything from T-shirts to hats and visors, sunglasses, even toilet items—everything you might have forgotten or decided you had to have.

One of the universal aspects of climbing each of the Seven Summits, save Vinson Massif, is the need to register and pay a park entry fee, just as if you were visiting the park for a single day. Often this was a perfunctory procedure, intended primarily to collect your money, but here it was taken very seriously. Tourism was the economic engine for this region—indeed of the country as a whole—and in years past there’d been too many deaths on the mountain. These threatened the lucrative trade. Because of the mountain’s benign reputation, ill prepared hikers had often thought to make the climb without bothering to register. Pushing up too quickly and with inadequate preparation, they’d died in shocking numbers. And though the lower camps were reached in relatively undemanding stages, summit day was exhausting. Nearly as many climbers on that day turned back as made it to the rim summit.

In addition to these deaths, too many climbers were simply lost. Presumably, they’d died up there somewhere and, given the prevalence of the wild carnivores that frequented the region, their bodies were never found. There’d been some shocking stories of the recovery of partial remains and the government had made a determined effort to end it all.

There were several routes to the summit, each of varying difficulty. And every one now had a mandated number of days for completion, a policy designed to slow the ascent. Guides and porters understood the necessity and were held accountable for what happened on their climbs. In addition, every climber had to present him or herself at Machame Gate for registration and to confirm the possession of adequate climbing gear. All of this was carefully noted, and when we exited the park at the Mweka Gate every name would be precisely checked off.

In spite of all the details, this was a very high profile climb, so the registration process went quickly. There were some 70 porters gathered, our gear and that needed for the climb already spread in a long line in the mud. Many of the porters were standing, but others were seated comfortably on the packs they’d soon carry. Park officials with clipboards moved slowly among them, checking off names, asking questions, confirming details.

I climbed from the van and stretched, taking in the scene as I did. Nearby were two large wooden signs cautioning that climbers must be fit to climb Kilimanjaro, advising that they must drink plenty of water, warning them not to push themselves. They also listed altitude sickness symptoms and urging climbers to immediately descend and seek medical attention if any appeared.

The Machame route was the most scenic and varied of all those on Kilimanjaro. One climber in four took it. The route started on the western side of the mountain, traversed around it to the southern side, and from there climbers tackled the summit. Two of the legs from one camp to another took us to a higher elevation before dropping down to a somewhat lower altitude for sleep. This was ideal for acclimating to the altitude, as it did not require any time-wasting back tracking, as was so common on major mountains.

One of the pleasures of this climb was that we’d pass through a series of ecological zones and, because the mountain rose so dramatically above a vast surrounding savanna, would at times command some of the most beautiful vistas on earth, or so I’d read. I’d brought my digital camera and promised myself that for once I’d take more than a handful of pictures.

Depending on where you started counting, there were either six or five of these zones. In general, we’d spend just a single day in each. The lowest was the cultivated region we’d driven through to get here. Today we’d trek through rainforest, with its morning mist and fog. Tomorrow would be open heather, a cool landscape with grasses and year-round flowers, many unique to this mountain.

After that came the moorland, a zone containing the iconic plants of Kilimanjaro, most not found anywhere else in the world. They weren’t terribly glamorous, from what I’d read though there were trees and plants with unique shapes. Mostly they were cabbage-like rosettes with tough leaves and giant groundsels. Large birds of prey were common, too, as were African hunting dogs—or even elephants.

Next was the Alpine desert, a fancy name for the barren region below the summit, a climate zone found everywhere on major mountains. Wind, high evaporation, bright sunshine in the thinning air, and wide variations in temperature—these were its hallmarks. Water was scarce, and the thin soil, along with the harsh conditions, meant there’d be few evidences of life there. There’d be some tough grass here and there, moss, and few animals other than those passing through. The views, however, would be stunning.

Finally came the summit, and what was there to say about that? Thin, dry air, extreme cold, snow and ice—it would be like nearly every other summit world-wide. We’d press up through a harsh environment to complete the climb, followed by a rapid descent. It was the one zone we’d be glad to see behind us.

Diana was busy with Hooker, who—I was sorry to see—looked to be in great shape. To my surprise, the president strolled over to me, accompanied by two serious looking men in sunglasses. They remained a respectful distance behind him, taking in the scene about us. The president extended his hand and we shook.

“I’m glad to see you here. I’m looking forward to visiting with you in the coming nights.”

“Thanks for inviting me.”

“I wouldn’t think of climbing a mountain without you.” He looked at ease. “I don’t expect any problems myself. I work out a bit and have always been athletic.” He reached into a pocket and extracted a pack of cigarettes. He lit one up without comment, standing erect, his chin slightly elevated in his characteristic pose. After a few puffs he said, “I read the mission reports about you on Elbrus, Aconcagua and Vinson Massif. Really something. You know, I often thought about working for the CIA myself. I think I’d have been an excellent agent. But I had a higher calling, you know?”

I spotted Msingi at the head of the line and heard him call back to the porters in Swahili. Those sitting stood up, and all lifted their loads. The president glanced toward the line without moving as he slowly smoked. Finally, I said, “Guess I’ll take my place.”

“No rush,” he replied. “No one’s going anywhere until I’m ready.” He flipped the cigarette into the mud and lit up another.

We set out for the first camp at late morning, Calvin joining me. Tom was somewhere back in the long line, having spent the night with Natasha. We were hiking at a steady, but curiously slow, pace through the lush rain forest that bands the base of Kilimanjaro. The porters and guides called out again and again, “Pole, pole, pole,”—“Slow, slow, slow.”

Each climber had a porter with him or her to carry necessities that did not form part of our heavier baggage. Most of the climbers, as did I, were carrying our own backpacks, so their load was light. That would likely change over the next few days.

“What did you do yesterday?” I asked Calvin.

“I visited one of the new albino orphanages,” he said.

“Albino?”

“Yes, Tanzania has the highest incidence of albinism in the world. There are more than 150,000 of them. They’ve always been considered bad luck, thought of as ghosts. It’s commonly held that they don’t die; they just disappear. It’s not unusual for parents to abandon an albino newborn. But now it’s much worse.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Witch doctors use the skin in ritual for all kinds of magic cures. They used to steal bodies and parts of bodies from graves. Once albinos had to hide from the sun, now they’re being hunted down like animals. Many have gone into hiding or protection simply to survive. Last year 25 albinos were killed, murdered by organized gangs who hack off arms, legs or genitals and leave their victims to die. Not long ago a seven-month-old baby was murdered. They took the head and a hand. The new story is that the ritual will give you good fortune, even make you rich. Fishermen weave human hair from albinos into their nets for good luck. The average annual income here is under $500 a year, Scott. A single limb from an albino can be sold for up to $2,000. In a country where superstition is so common, a reign of terror has descended on these unfortunates. Grown albinos and those with newborn albinos are moving to the cities, where they are safer. Now orphanages are springing up to take the abandoned children in and protect them. That’s where I was.”

“Isn’t the government doing anything?”

“Sure, once they got embarrassed from all the international publicity. There are over two hundred gang members in jail for these assaults and murders, but only a handful have come to trial.” Calvin stared out the window before continuing. “When they bury an albino they have to seal the grave in cement to protect the body.”

It was an old story. One I’d seen all over the world. America is no more egocentric than any other country, but in recent decades there’s been a vocal group who tends to blame us for every wrong in the world. We’re the source of all the evil everywhere. They know nothing. Intolerance, racism, superstition are pandemic world-wide, and while it was true there were enlightened cultures, I’d not found any more tolerant than my own country. Mexico, for one, complained bitterly about how Mexicans illegally in the United States were treated, but in Mexico, illegals were thrown into jail as criminals and promptly deported. Guatemalans entering Mexico’s southern border illegally were routinely beaten, and often the women were raped before being tossed back into their own country.

Tanzania was a beautiful country, with smiling, friendly people—some of whom hunted down and hacked the limbs off those born different from themselves. The very thought was depressing.

Three hours into the trek we broke for lunch. The meal had been prepared before we set out and consisted of sandwiches and fruit. And though the pace had been very slow, we were rising steadily up the mountain and I was grateful for the break. The porters sat on their loads and spoke with animation amongst themselves. Today had been nothing more than a stroll for them. I spoke briefly to Tom, who confessed he’d slept for only about an hour the night before. Lucky man.

I was soon bored with the delay and took a walk in the nearby jungle. I was stunned at what I saw. Climbers had been using the area out of sight bordering the route as a public latrine. There was toilet paper everywhere. There were portable potties set up for our use, as this was the usual lunch stopping point, but too many climbers ignored them.

I’d seen all this before. People went on climbs to be with nature, to take in the majestic beauty of a major mountain and its environs, then promptly dumped their trash and defecated at random. Base camp at Everest was widely known for the public dump there. The consequence of all this, besides the trashing of what should have been pristine land, was needless exposure to bacteria and, in particular, to the intestinal infirmities that went with it. This was the primary reason illness was so prevalent on this climb.

Back on the trail, I went to the water station and refilled my bottles. I was carrying two quarts, as were most of us. Porters refilled a container at every stop. The container had a state-of-the-art filtration system, so it dispensed safe water. If we relied on the natural occurring water along the way, we’d all fall sick from the contamination, and among the westerners, at least, there’d be a few deaths. Kilimanjaro might appear pristine from a distance, the climbers might pretend they were in the wilds of an African Eden, but they’d turned the routes up the mountain into toxic zones.

When we resumed, Onesphory came back to hike with me. Calvin, I saw, was now up near the president and his party. I glanced at the young and appreciated again what an uncommonly handsome young man he was. There was a very pleasant blending of the best features of his father and mother.

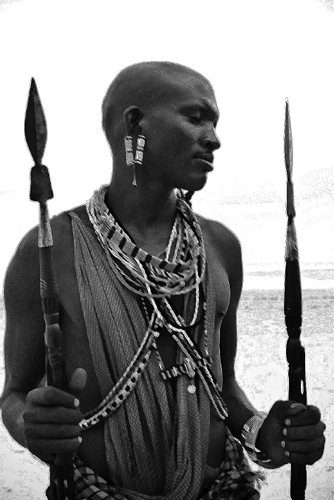

“That was quite a dance you performed yesterday,” I said.

He smiled sheepishly. “It is the welcome dance of a Chagga warrior. It is meant to let the visitor know he is welcome, but also it says that we are great warriors and not to be taken lightly.”

“It was wonderful. I’ve never seen anything like it before.”

“You really liked it, then?”

“Oh, yes, everyone did. You were amazing.”

“In the village, when we were boys, we often mimicked the men who performed it. I didn’t have much time to practice—but I thought it went all right.”

“Better than all right. You did very well.” He dropped his head in embarrassment. “Your village seems like a very pleasant place,” I added casually.

“It was wonderful growing up there. They are very good people.”

I smiled. “It must have helped for your father to be the clan chief.”

He laughed. “My friends were given a few whacks with a cane when they were caught misbehaving. That doesn’t include what their parents did when they got home. But because I was the chief’s oldest they just yelled at me—and my father is a very tolerant man. I got away with murder, I think you Americans say. It was a good childhood. I hated to leave.”

“How’d you get along with your brother?”

He hesitated. “When we were young we were very close, but as I got older and went off to school it was different. He is secretive. He’d often go away for hours at a time and then come back and say nothing about what he’d been doing or where he’d been.”

“Where’d you go to school?”

“Not far away in kilometers, usually a four-hour drive, but very far away in every other way. It was a British boarding school in Dodoma. The international English-speaking community send their children to the school, and so do the Tanzanian families who want their sons to have the exposure and education. I was very lonely at first, but I made many friends.”

“Is this common for the sons of chiefs?”

“Oh, no. It is not usual at all. But I thought the clan was paying my way. I knew my parents didn’t have the money.”

Msingi gave the order for us to set out, and slowly the long line resumed its way. Onesphory stayed with me. The porters kept up their pleasant chant and, with wide grins, urged us all to slow the pace. “Pole, pole, pole.” Onesphory pointed out the birds in the trees, along with a few monkeys and the beauty about us.

We had some demanding days ahead of us, and too brisk a pace this first day would make all of them more difficult. In fact, the brush often rustled, indicating the presence of an unseen, scurrying animal. I’d spotted nibble monkeys in the trees, heard their chatter, and identified the cawing of many birds, most of which I could not spot.

After a bit I said, making it sound as much like a question as I could, “I guess learning your biological father is the President of the United States came as quite a shock?” I found the entire situation peculiar. I suppose I was too much a cynic to be profoundly moved by the sentimentality that had gripped the American and Tanzanian public and the International media.

He hesitated. “My father is a good man. It’s true that I was always closer to my mother and he seemed to favor my young brother, Itosi. But my father was good to me. At first I thought I was sent to the school as punishment, especially after my brother did not join me when he came of age. I see now the truth.”

“How has your brother taken all this?”

“From the first it was hard, since I was oldest, but that is not new when the chief has two sons. It was obvious I had a benefactor when I went to school, but like I said, I always thought it was the clan. My brother would tease me about it, like he knew something I didn’t. When I went off to college, though, it was obvious that someone or some group with money had taken an interest in me. I asked about it but got no answers from my parents. Itosi resented me very much then.”

“How did you enjoy the UK?”

Onesphory grinned then told me about his time there, about climbing in Scotland, meeting Ian and Brendan, then going to the United States.

“How do you like Harvard?”

“It is okay. I find it strange. I have a hard time understanding Americans, but I’m trying, especially since it turns out I’m half American myself.” He laughed. “Having my friends Ian and Brendan there has been a big help.”

After we crossed another of the many small streams along the route I asked if he’d made plans for after school.

“Oh, yes, I will return to my village and be chief someday.”

“Really?” I was very surprised at the answer. “I would think… well, I’d think, in light of all that has happened, your plans would have changed.” I couldn’t see the son of the American president and a Harvard graduate living in a Tanzanian hut, no matter how nice the people.

“I am no different than I was, despite all that has happened. I always meant to go home. My people have many needs, and I think with my training and education I can help. Mining and selling tanzanite only employs so many people and to rely so much on tourism is wrong.” Tanzanite is a rare blue gemstone only found in the Kili foothills. It’s illegal mining and selling was a cottage industry locally. “Both are slowly destroying the Chagga people especially tourism. And though the tourists don’t see it, the land is also slowly being destroyed. Our population keeps growing, and our way of life depends on farming. Every year we cut down forest we need for our future. And you must know of the terrible superstitions that fill the hearts of too many of our people. Terrible things are done because of them. No, I will return to my village and be chief.”

What I wanted to ask was if it was still possible, now that it was known that the chief was not his father. Certainly, his younger brother must be considering an alternative. Instead I asked, “Did you suspect you had a different father?”

He paused before answering. “No, though when I read it on the Internet, I must say, it was not a surprise—just who he was.”

“It had been a secret for so long, how did it come out?”

“I don’t know. No one seems to know.” In a quiet voice he added, “My mother is very upset about it.”

“I guess everything has changed,” I said sympathetically.

The young man turned sad for a moment. “It is all different,” he said wistfully. Then he grinned. “But very exciting.”