1. By Manzikert’s time, the rough southern accent of his people had permanently changed the designation “Captain” to “Cappan.” “Captain” referred not only to Manzikert’s command of a fleet of ships, but also to the old Imperial titles given by the Saphants to the commander of a see of islands; thus, the title had both religious and military connotations. Its use, this late in history, reflects how pervasive the Saphant Empire’s influence was: 200 years after its fall, its titles were still being used by clans that had only known of the Empire secondhand.

2. A footnote on the purpose of these footnotes: This text is rich with footnotes to avoid inflicting upon you, the idle tourist, so much knowledge that, bloated with it, you can no longer proceed to the delights of the city with your customary mindless abandon. In order to hamstring your predictable attempts—once having discovered a topic of interest in this narrative—to skip ahead, I have weeded out all of those cross references to other Hoegbotton publications that litter the rest of this pamphlet series like a plague of fungi.

3. I should add to footnote 2 that the most interesting information will be included only in footnote form, and I will endeavor to include as many footnotes as possible. Indeed, information alluded to in footnote form will later be expanded upon in the main text, thus confusing any of you who have decided not to read the footnotes. This is the price to be paid by those who would rouse an elderly historian from his slumber behind a teaching desk in order to coerce him to write for a common travel guide series.

4. Today, the salinity of the river changes to fresh water a mere 25 miles upriver; the reason for this change is unknown, but may be linked to the build-up of silt at the river’s mouth, which acts as a natural filter.

5. Almost 500 years later, the Petularch Dray Mikal would order the uprooting of native flora around the city in favor of the northern species of his youth, surely among the most strikingly arrogant responses to homesickness on record. The Petularch would be dead for 50 years before the transplantation could be ruled a success.

6. And yet, what is our understanding of the monk’s early history? Obscure at best. The records at Nicea contain no mention of a Samuel Tonsure, and it is possible he was just passing through the city on his way elsewhere and so did not actively preach there. “Samuel Tonsure” may also be a name that Tonsure created to disguise his true identity. A handful of scholars, in particular the truculent Mary Sabon, argue that Tonsure was none other than the Patriarch of Nicea himself, a man who is known to have disappeared at roughly the same time Tonsure appeared with Manzikert. Sabon offers as circumstantial evidence the oft repeated story that the Patriarch sometimes traversed his city incognito, dressed as a simple monk to spy on his subordinates. He could easily have been captured without knowledge of his rank—which, if revealed, would have given Manzikert such leverage over Nicea that he might well have been able to take the city and settle behind its walls, safe from Brueghel. If so, however, why didn’t the Patriarch make any attempt to escape once he had gained Manzikert’s trust? The case, despite some of Sabon’s other evidence, seems wrong-headed from its inception. My own research, corroborated by the Autarch of Nunk, indicates that the Patriarch’s disappearance coincides with that of the priestess Caroline of the Church of the Seven Pointed Star, and that the Patriarch and Caroline eloped together, the ceremony performed by a traveling juggler hastily ordained as a priest.

7. For reasons which will become clear, Tonsure could no longer complete it; therefore, 10 years later, Manzikert’s son had another Truffidian monk summoned from Nicea for this purpose. Unfortunately, this monk, whose name is lost to us, believed in wearing hair shirts, daily flagellation, and preaching “the abomination of the written word.” He did indeed complete the biography, but he might as well have spared himself the effort. Although edited by Manzikert II himself, it contains such prose as “And his highly exhulted majesty set foot on land like a swaggorin conquor from daes of your.” Clearly this abominator’s abominations against theWritten Word far outweigh any crimes It may have perpetrated upon him.

8. If the careful historian needs further proof that Sabon is wrong, he need look no further than the inscription on the monk’s journal: “Samuel Tonsure.” Why would he bother to maintain the pretense since the contents of the journal itself would condemn him to death? And why would he, if indeed the Patriarch (a learned and clever man by all accounts), choose such a clumsy and obvious pseudonym?

9. All quotes without attribution are from Tonsure’s journal, not the biography.

10. Quote taken from the biography. One wonders: if the Cappan was so fierce, how much more fearsome must Michael Brueghel have been to make him flee the south?

11. The Cappan’s appending “II” to his son’s name gives us an early indication that he meant to settle on land and found a dynasty. The Aan clan would have thought the idea of a dynasty odd, for usually cappans were chosen from among the ablest sailors, with hereditary claims a secondary consideration.

12. I find it necessary to interject three observations here. First, that the paragraph on the gray caps written for the Cappan’s biography is far worse, describing as it does “small, piglike eyes, a jowly jagged crease for a mouth, and a nose like an ape.” The gray caps actually looked much like the mushroom dwellers of today—which is to say, like smaller versions of ourselves—but the Cappan was already attempting to dehumanize them, and thus create a justification, a rationalization, for depriving them of life and property. Second, and surprisingly, evidence suggests that the gray caps wove their clothing from the cured pelts of field mice. Third, Tonsure appears to have given away a secret—if, in fact, the gray cap they met came “only to the Cappan’s shoulder” and the gray caps averaged, by Tonsure’s own admission, three-and-one-half feet in height (as do the modern mushroom dwellers), then the Cappan could only have stood four and one-half feet to five feet in height, something of a midget himself. (Is it of import that in a letter concerning future trade relations written to the Kalif, Brueghel calls Manzikert “my insignificant enemy,” since “insignificant” in the Kalif’s language doubles as a noun meaning “dwarf” and Brueghel, who wrote his own letters of state, loved word play?) Perhaps Tonsure’s description of Manzikert in the biography was dictated by the Cappan, who wished to conceal his slight stature from History. Unfortunately, the Cappan’s height, or lack thereof, remains an ambiguous subject, and thus I will stay true to the orthodox version of the story as related by Tonsure. Still, it is delicious to speculate. (If indeed Manzikert was short, we might have hoped he would look upon the gray caps as long-lost cousins twice removed. Alas, he did not do so.)

13. We can only speculate as to why Manzikert should find children and mushrooms repulsive. He certainly ate mushrooms and had had a child with Sophia. Perhaps, if indeed undertall, his nickname growing up had been “little mushroom”?

14. As this is the first and last time the gray caps actively attempted to communicate with the Aan, one wonders just what the gray cap was saying to Manzikert. A friendly greeting? A warning? The very loquaciousness of this particular gray cap in relation to the others they were to encounter has led more than one historian to assume that he (or she—contrary to popular opinion, there are as many female gray caps as male; the robes tend to make them all look unisexual) had been assigned to greet the landing party. What opportunities did Manzikert miss by not trying harder to understand the gray cap’s intent? What tragedies might have been averted?

15. Tonsure was criminally fond of Oliphaunts. References to them, usually preceded by mundanea like “as large as” or “as gray as,” occur 30 times in the journal. Possessed of infinite mercy, I shall spare you 28 of these comparisons.

16. Tonsure’s description in the biography also includes a series of mushroom drawings by Manzikert—an attempt to “appear sensitive,” Tonsure sneers in his journal—from which I provide three samples for the half dozen of you who are curious as to the Cappan’s illustrative skills:

17. Apparently, since Tonsure fails to describe it.

18. The mammologist Xaver Daffed maintains that these were “actually cababari, a stunted relation of the pig that resembles a rat.” (Quote taken from The Hoegbotton Guide to Small, Indigenous Mammals.) If so, then, as subsequent events will show, the rats of Ambergris have managed something of a public relations coup; the poor cababari are today extinct in the southern climes.

19. James Lacond has suggested that the fungus had hallucinogenic qualities. Tonsure, for his part, sampled a “fungus that resembled an artichoke” and found it tasted like unleavened bread; he reports no side effects, although Lacond claims that the rest of Tonsure’s account must be considered a drug-induced dream. Lacond further claims that Tonsure’s later account of Manzikert’s men glutting themselves on the fungi—some of which tasted like honey and some like chicken—explains their sudden mercilessness. But Lacond contradicts himself: if the rest of Tonsure’s account is a fever dream, then so is his description of the men eating the fungus. As always when discussing the gray caps, debate tends to describe the same circles as their buildings. (A similar circularity drove Lacond, late in his life, to declare that the world as we know it is actually a product of the dream dreamt by Tonsure. Since our knowledge of our identity as Ambergrisians, where we came from, is so dependent on Tonsure’s journal, this is close to the heresy of madness.)

20. Admittedly, a perilous and notoriously inaccurate undertaking; the mushroom dwellers tend to look unkindly upon intrusions into their territory.

21. The question of where the gray caps came from and why they were concentrated only in Cinsorium remains a mystery. The subject has frustrated many a historian and, to avoid a similar fate, I shall pass over it entirely.

22. But surely they farmed the fungus?

23. Tonsure reports the following symbol showed up repeatedly:

24. Volume XX, Issue 2, of The Real History Newsletter, published by the Ambergrisians For The Original Inhabitants Society.

25. In a city otherwise so pristine, such blatant “disorder” should have made Tonsure suspicious. Was he now so completely set, as was his master, on the goal of discrediting and dehumanizing the gray caps, that he could see it no other way?

26. Unfortunately, this claim strengthens Sabon’s assertion with regard to the Patriarch of Nicea—see footnote 6.

27. Poor Tonsure. Just preceding this diatribe, the monk describes a kind of hard mushroom, about seven inches tall, with a stem as thick as its head. When squeezed, this mushroom suddenly throbs to an even greater size. While walking innocently between the “library” and the amphitheater, Tonsure came across a group of gray cap women using these mushrooms in what he calls a “lascivious way.” So perhaps we should forgive him his hyperbole. Still, shocked or not—and he was a more worldly monk than many—Tonsure should have noticed that for every such “perversion,” the gray caps had developed a dozen more useful wonders. For example, another type of mushroom stood two feet tall and had a long, thin stem with a wide hood that, when plucked, could be used as an umbrella; the hood even collapsed into the stem for easy storage.

28. Here, for once, Lacond proves useful. He puts forth two theories for the gray caps’ passivity: first, that Manzikert had landed in the midst of a religious festival during which the gray caps were forbidden to take part in any aggressive acts, even to defend themselves; second, that the gray cap society resembled that of bees or ants, and thus none of the “units” in the city had free will, being extensions of some hive intellect. This second theory by Lacond seems extreme to some historians, but the idea of passivity being bred into particular classes of gray cap society cannot be ruled out. This would support my own theory that the entire city of Cinsorium was a religious artifact, a temple, if you will, in which violence was not permitted to be inflicted by its keepers. Were Manzikert’s actions tantamount to desecration?

29. Typically, Sabon cannot bite her tongue and disagrees, citing the Calabrian Calendar used by the Aan as schismatic—most definitely not synchronized with the modern calendar. However, Sabon fails to take into account that Tonsure, as the non-Aan author of the biography and the journal, would have used the Kalif’s calendar, which is identical to our own.

30. Cynically, Tonsure reports, “Better to name a city after the nether parts of a whale than to actually go whaling, for Manzikert, lazy as he is, finds piracy much easier than whaling: when you harpoon an honest sailor, he is less likely to drag you 300 miles across open water and then, turning, casually devour you and drown your companions.” Other names Manzikert considered include “Aanville,” “Aanapolis,” and “Aanburg,” so we may be fairly certain that Tonsure suggested “Ambergris,” despite his ridicule of the name.

31. Or, as Sabon put it, “how cunning a fungus.”

32. Tonsure does, in his journal, write that the lichen in question “more closely resembled one blob rutting with another blob, but who is to doubt the vision of cappans?” Are we to believe that the carnage to come was all the result of two unfortunately-shaped lichen? Sabon points to the Holy Visitation of Stockton (alternately known by historians as the Sham Involving Jam), where a stain of blueberry jam resembling the heretic Ibonof Ibonof sparked seven days of riots. Lacond, in agreement with Sabon, relates the story that the Kalif’s order to attack the Menite town of Richter was the direct result of a Richter lemon squirting him in the eye when he cut it open. Unfortunately, Sabon and Lacond have joined forces to support an idea that lacks merit given the context. It is my opinion that, lichen or no lichen, Manzikert would have attacked the gray caps.

33. Tonsure never indicates what he did during the massacre—whether to participate or intervene; later circumstantial evidence indicates he may have tried to intervene. Nonetheless, Tonsure’s description of the massacre has a disturbingly cold, disinterested edge to it. Predictably, the biography account speaks of Manzikert’s bravery as, surrounded by “dangerous gray caps armed to the teeth,” (read: “wide-eyed, weaponless midgets”) he managed to cut his way through them to safety.

34. The bersar, an honorary title peculiar to the Aan and awarded only to men who had shown great bravery in combat.

35. All the information we have about the events that follow comes from Manzikert II, who is not nearly as entertaining as Tonsure, lacking both his wit and powers of description. Manzikert II was serious and 17—a disastrous combination for historical writing, as I can attest—and I have resisted direct quotation for the most part.

36. The gray caps must also have taken the fabulous golden tree, for there is no mention of it in Manzikert II’s account, or in any future chronicle. It defies the laws of probability that such a remarkable invention would not be mentioned somewhere, in some account, had it not already been taken back by the gray caps.

37. I will call him Manzikert I from this point on, so as to avoid confusing him with his son.

38. Lacond: “An act of utter barbarism, destroying the finest artifacts of a culture that has never been found anywhere else in the known world and destroying a people both peaceful and advanced. Genocide is too kind a word.” Sabon: “Without Sophia’s bravery, the new-born city of Ambergris would soon have perished, undone by the treachery of the gray caps.”

39. Sophia, in the biography, would have us believe that she destroyed all of the buildings, but since we find Manzikert II, 10 years later, using several of them for defensive and storage purposes, this seems unlikely.

40. We begin to wonder if Manzikert did believe in his heart of hearts that he should massacre the gray caps because of two oddly-shaped lichens.

41. So many that Manzikert II had to ban the feeding of rats during a time of famine.

42. Much to the disgust of Truffidians everywhere, Manziists often claim to be the Brothers and Sisters of Truff, a claim that has led to riots—and dozens of rats cooked on spits—in the Religious Quarter.

43. The impatient, feckless reader, possessed of no glimmer of intellectual or historical curiosity, should do an old historian a favor and skip the next few pages, proceeding directly to the Silence itself (Part III). I would assume that, in these horrid modern times, that will include most of you. Of course, those readers least likely to read these footnotes, and thus least likely to appreciate the next few pages, will skip this note and bore themselves upon the ennui of history . . .

44. Sophia was never the same after Manzikert I returned to her blinded and deranged—she died soon after him and while alive expressed little or no interest in governing, although she did on at least two occasions, at her son’s insistence and with great success, lead punitive expeditions against the southern tribes. Sophia had truly loved her brute of a man, although not in the maudlin terms described by Voss Bender in his first and least successful opera, The Tragedy of John and Sophia; it is difficult not to laugh while John dances with a man in a rat suit, which he has mistaken in his madness for Sophia, toward the end of Act III.

45. He was, by all accounts, a handsome man, if not possessed of the swarthy, thick handsomeness of his father; he had a slender frame and a head topped with a tangle of black hair, beneath which his green eyes shone with a cunning fierceness.

46. For a long time, these tribes avoided the city and accorded the new settlement an undue measure of respect—until they began to realize the gray caps had left, apparently for good, after which a vigorous contempt for the Aan became the norm.

47. For a thorough overview of the early political and economic systems, as well as particulars on crops, etc., see Richard Mandible’s excellent “Early Ambergrisian Finance and Society,” recently published in Vol. XXXII, Issue 3, of Historian’s Quarterly. Such detailed information lies beyond the brief of this particular essay, not to mention the patience of the reader and the endurance of an old historian with creaky joints.

48. A catalog kept during Manzikert II’s reign indicates that at least two of these relics were taken from saintly men while still living, and that although the Cappan’s agents bargained long and hard for the purchase from the Kalif of the “penis and left testicle of Saint George of Assuf,” they managed only to procure the testicle. (We can only imagine the bizarre sight of the testicle’s triumphant entrance to the city, borne upon a perfumed, gold-embroidered pillow held high by a senior Truffidian priest while the crowds cheered wildly.) At the height of the religious frenzy, the Church of the Seven Pointed Star even put together an array of different saints’ body parts—a head here, an ear there—to make a creature they called the “The Saint of Saints,” a sort of super saint. This was put on display for 20 years until several other churches, on the verge of bankruptcy due to their own lack of relics, launched a joint raid and “dismembered” this early golem.

49. The rebuilt palace elicited neither condemnation nor praise; indeed, its most interesting features were its many interior murals and portraits, several of which commemorate victories against the Kalif created out of thin air by Ambergrisian historians. Worse, the first two portraits in the Great Hall depict cappans who never existed, to gloss over the Occupation, a period when the city was under the Kalif’s control. To this day, Ambergrisian school children are taught the exploits of Cappan Skinder and Cappan Bartine. Braver if less substantial leaders have rarely trod upon the earth . . .

50. Evidence suggests he may have been poisoned by his ambitious son, whom he was always careful to bring on campaign with him, so as to keep the boy under a watchful eye. Manzikert II died suddenly, with no apparent symptoms, his body quickly cremated on his son’s order. If there was little protest, this may have been because he had never been a popular leader, despite his excellent record. He lacked the necessary charisma for men to follow him unthinkingly.

51. In the north, the Cappandom of Ambergris, as it was now officially known, encountered implacable resistance from the Menites, adherents to a religion that saw Truffid as heresy. The Menites would subsequently establish a vast northern commercial empire, based in the city of Morrow, some 85 miles upriver from Ambergris.

52. Sabon insists it was leprosy, while others believe it was epilepsy. Regardless, we can choose from three spectacular diseases with very different symptoms.

53. Jungle rot can have various manifestations, but, according to an anonymous observer, Manzikert III’s jungle rot was among the nastiest ever recorded: “Suddenly an abscess appeared in his privy parts then a deep-seated fistular ulcer; these could not be cured and ate their way into the very midst of his entrails. Hence there sprang an innumerable multitude of worms, and a deadly stench was given off, since the entire bulk of his members had, through gluttony, even before the disease, been changed into an excessive quantity of soft fat, which then became putrid and presented an intolerable and most fearful sight to those who came near it. As for the physicians, some of them were wholly unable to endure the exceeding and unearthly stench, while those who still attended his side could not be of any assistance, since the whole mass had swollen and reached a point where there was no hope of recovery.”

54. Although Manzikert III’s order (rescinded after his death) was extreme, his charge that the city’s doctors knew little of their craft is, unfortunately, true. In an attempt to upgrade its service, the Institute sent representatives to the Kalif’s court, as well as to the witchdoctors of native tribes. The Kalif’s physicians refused to reveal their methodology, but the witchdoctors proved very helpful. The Institute incorporated such native procedures as applying the freshwater electric flounder as a local anesthetic during surgery. Another procedure, perhaps even more ingenious, solved the problem of infection during the stitching up of intestines. Large senegrosa ants, placed along the opening, clamped the wounds shut with their jaws; the witchdoctor then cut away the bodies, leaving only the heads. After replacing the intestines in the stomach, the witchdoctor would sew up the abdomen. As the wound healed, the ant heads would gradually dissolve.

55. Although I have certainly devoted enough footnotes to him.

56. One menu for such a banquet included calf’s brain custard, roast hedgehog, and a dish rather cruelly known as Oliphaunt’s Delight, the incomplete recipe for which was uncovered by the Ambergrisian Gastronomic Association just last year:

1 scooped out oliphaunt’s skull

1 pureed oliphaunt’s brain

1 gallon of brandy

6 oysters

2 very clean pigs’ bladders

24 eggs

salt, pepper, and a sprig of parsley

I am unhappy to report that the search is on for the missing ingredients.

57. In all fairness to Manzikert III, Sharp had an insufferable ego. His autobiography, published from the unedited manuscript found on his body, contains such gems as, “From East and West alike my reputation brings them flocking to Morrow. The Moth may water the lands of the Kalif, but it is my golden words that nourish their spirit. Ask the Brueghelites or the followers of Stretcher Jones: they will tell you that they know me, that they admire me and seek me out. Only recently there arrived an Ambergrisian, impelled by an insurmountable desire to drink at the fountain of my eloquence.”

58. The Scathadian novelist George Leopran—prevented by Manzikert III from sailing home—had an experience almost as bad, returning to Scatha only after much tribulation: “I boarded my vessel and left the city that I had thought to be so rich and prosperous but is actually a starveling, a city full of lies, tricks, perjury and greed, a city rapacious, avaricious and vainglorious. My guide was with me, and after 49 days of ass-riding, walking, horse-riding, fasting, thirsting, sighing, weeping, and groaning, I arrived at the Kalif’s court. Even this was not the end of my sufferings, for upon setting out for the final stretch of my journey, I was delayed by contrary winds at Paust, deserted by my ship’s crew at Latras, unkindly received by a eunuch bishop and half-starved on Lukas and subjected to three consecutive earthquakes on Dominon, where I subsequently fell in among thieves. Only after another 60 days did I finally return to my home, never again to leave it.” If he had known that an arthritic Ambergrisian historian would some day find his account hilarious, he might have cheered up. Or perhaps not. In any event, we can certainly understand historical novelists’ tendency to vilify Manzikert III beyond even his due.

59. We will never know why Aquelus was accepted so readily, unless Manzikert III had proclaimed him ruler on his deathbed or Manzikert II, knowing his son’s sickly nature, had already decreed that if Manzikert III died, Aquelus should take his place. The story that, in his childhood, a golden eagle alighted at Aquelus’ bedroom window and told him he would one day be cappan is almost certainly apocryphal.

60. Three centuries later, city mayors all along the Moth would cast off the yoke of cappans and kings and create a league of city-states based on trade alliances—eventually plunging Ambergris into its current state of “functional anarchy.”

61. The first festival, held by Manzikert I, had been a simple affair: a two-course feast attended by an elderly swordswallower who managed to impale himself. More elaborate entertainments would mark the reign of Aquelus in particular. Such celebrations included a representation of the Gardens of Nicea, 300 yards across, built on rafts between the two banks of the Moth, complete with flowers, trees of brightly-colored crystal, and an artificial lake stocked with fish, from which guests were to choose their dinner before retiring to a banquet. In the year after the Silence, at a touch from the Cappaness’ hand, an outsized artificial owl sped around the public courtyard, sparking off a hundred torches as it, finally, came to rest on an 80-foot high replica of the Kalif’s Arch of Tarbut. But perhaps the most audacious presentation occurred during the reign of Manzikert VII, who resurrected the gray caps’ old coliseum, sealed it off, had the arena flooded with water, and recreated famous naval battles using ships built to 2/3 scale. All this pomp and circumstance served as genuine celebration, but also, in later years, to hide the city’s growing poverty and military weakness.

62. Fourth Census—on file in the old bureaucratic quarter.

63. Lacond’s most ridiculous “theory” according to most historians (and therefore well worth relating) postulates that some mushroom dwellers actually gestated within such mushrooms. This explains both why the axe blows to fell them caused the mushrooms to shriek and why their centers often proved to be composed of a dark, watery mass reminiscent of afterbirth or amniotic fluid. I myself now believe they “shrieked” because this is the sound a certain rubbery consistency of fungi flesh makes when an axe cleaves it; as for the “afterbirth,” many fungi contain a nutrient sac. We could wish that Lacond had done more research on the subject before venturing an opinion, but then we would be bereft of his marvelous stupidity.

64. By now in his late sixties, Bacilus was a fiery old man with a smoking white beard who must have made quite a spectacle in public.

65. In the Council’s defense, Bacilus had a rather checkered reputation in Ambergris. We have, today, the luxury of distance, but the Council had had no time to expunge from memory such Bacilus innovations as artificial legs for snakes, mittens for fish, or the infamous Flying Jacket. Bacilus reasoned that if trapped air will make an object float upon the water, then trapped air might also allow an object, in this case a man, to float upon the air. Therefore, Bacilus created a special body suit he called the Flying Jacket. Made from hollowed out pig and cow stomachs, it consisted of three dozen air sacs sewn together. Without prior testing, Bacilus persuaded his cousin Brandon Map to don the Flying Jacket and, in front of some of Aquelus’ foremost ministers, to jump from the top of the new Truffidian Cathedral. After the poor man had plummeted to his death, it was generally observed within Bacilus’ earshot, if only to make the loss appear not completely pointless, that yes, perhaps his cousin had flown a little bit before the end. Another minister, less kindly, remarked that if Bacilus himself, surely a natural windbag if ever he’d seen one, had donned the jacket, the results might have been different, for it was obvious that Brandon had no air within him anymore, nor blood, nor bones . . . The Truffidians were, of course, horrified that their new cathedral had been christened with such a splatter of blood—and even more upset when they discovered Brandon had been an atheist. (I should note, however, that Truffidians have spent the last seven centuries being horrified by some event or other.)

66. This police report filed by Richard Krokus provides a typical example: “I woke in the middle of the night to a humming sound from the kitchen. It must have been two in the morning and my wife was by my side, and we have no children, so I knew no one who was supposed to be in the house was fixing themselves a midnight snack. So I go into the kitchen real quiet-like, having picked up a plank of wood for a weapon that I was going to use to reinforce the mantel, but hadn’t gotten around to on account of my bad back—I served like everyone in the army and messed up my back when I fell during training exercises and even got disability payments for awhile, until they found out I’d slipped on a tomato—and my wife had been nagging me to fix the mantel so I picked up the wood—from the store, first, I mean, and then that night I picked it up, but not so as to fix the mantel, you know, but to defend myself. Where was I? Oh, yes. So I go into the kitchen and I’m already thinking about making myself a sandwich with the left-over bread, so maybe I’m not paying as much attention as I should to the situation, and I’ll be f—if there isn’t this little person, this wee little person in a great big felt hat just sitting on the countertop, stuffing its face with the missus’ chocolate cake. I looked at it and it looked at me, and I didn’t move and it didn’t move. It had great big eyes in its head, and a small nose, and a grin like all get out, only it had teeth, too, real big teeth, so it kind of spoiled the cheerfulness. Of course, it had already spoiled my wife’s cake, so I was going to hit it with my plank of wood, only then it threw a mushroom at me and next thing I know it’s morning and not only is the cake completely gone, but my wife is slapping my face and telling me to get up have I been drinking again don’t I know I’m late for work. And later that day, when I’m setting the plates for dinner, I can’t find any of the knives or forks. They’re all gone. Oh, yes, and I almost forgot—I couldn’t find the mushroom that hit me, either, but I’m telling you, it was heavier than it looked because it left this great big bump on top of me head. See?”

67. A few local souvenir shops, hoping to cash in on the pilgrim business, had begun to sell small statues and dolls of the mushroom dwellers, as well as potpourris made from mushrooms; a singular tavern called “The Spore of the Gray Cap” even sprouted up. (This tavern still exists today and serves some of the best cold beer in the city.)

68. Aquelus, in a brilliant maneuver, sent, along with his ambassador suggesting marriage, a bevy of Truffidian monks to Morrow, to negotiate a religious compromise that would allow the Menite kingdom and the Truffidian cappandom to reconcile their differences. Many of the arguments were extremely obscure. For example, the Menites believed God was to be found in all creatures, while the Truffidians, in their attempts to disassociate themselves from Manziism, believed rats were “of the Devil”; after weeks of ridiculous testimony on the merits (“their fur is pleasant to stroke”) and deficiencies (“they spread disease”) of rats, the compromise was that “of the Devil” should be struck from the Truffidian literature and replaced with the language “not of God” (originally changed to “made of God, but perhaps strayed from His teachings,” but the Truffidians would not accept this). After a tortuous year of negotiation, and possibly more from exhaustion and boredom than because anyone actually believed in it, a settlement was reached, much to the relief of both rulers (who, although religious, had a strong streak of pragmatism). This agreement would last for 70 years, until made void by the Great Schism, and even then the dissolution of the contract transpired through the offices of the main Truffidian Church in the lands of the Kalif.

69. Chroniclers of the period call the marriage one of convenience, as evidence suggests Aquelus was a homosexual. But if begun in convenience, it soon deepened into mutual love. Certainly nothing rules out the possibility of Aquelus being bisexual, much as the homosexual scholar cappan of Ambergris, Meriad, writing two centuries later, would have us believe Aquelus was as bent as a broken bow.

70. Given Sophia and Manzikert I’s example, it is not surprising that, until the fall of Trillian the Great Banker and his Banker Warriors, women served in the army, many of them attaining the highest ranks. Irene herself excelled as a hunter, could outrun and outfight the fastest of her five brothers, and had studied strategy with no less a personage than the Kalif’s brilliant general, Masouf.

71. Please note that in these several references to the Kalif over the past 60 years, I have been referring to more than one ruler. The Kalif was chosen by secret ballot, and his identity never revealed, so as to protect against assassination attempts. Each Kalif was called simply “the Kalif.” It is little wonder that the position of Royal Genealogist has so few rewards and so many frustrations.

72. If this arrangement seems extreme, we should consider that in effect the vassalage meant nothing—the Kalif was far too busy consolidating his recent eastern conquests (rebellions in these lands secretly funded by Aquelus, who left nothing to chance) to exact tribute or even send his own administrators to oversee the Cappandom. However, the Kalif may have outmaneuvered Aquelus in this regard, since in later centuries his successors would claim that the Cappandom of Ambergris belonged by right to them and would wage war to “liberate” it.

73. When Stretcher Jones was finally defeated, in a bloody battle that consolidated the Kalif’s western supremacy for 300 years, Aquelus responded with the following words: “Being a friend of both sovereigns, I can only say, with God: I rejoice with them that do rejoice and weep with them that weep.”

74. Even before Stretcher Jones’ fall these fierce warriors had been driven east by the slowly-advancing armies of the Kalif, who most certainly wished for them to weaken Ambergris. They have since passed out of history in a manner both shocking and absurd, but tangential to the concerns of this essay; suffice it to say that exploding ponies do not a pretty sight make, and that no one knows who was responsible for the worms.

75. With access to the sea blocked in this way, it is hardly surprising that Ambergris did not become the dominant naval power in the region until the days of Manzikert V, who established the Factory: a world-renowned shipbuilding center that could produce a galley in 12 hours, a fully-armed warship in two days.

76. And, coincidentally, providing Aquelus with an excellent example of what happens when an army with a strong cavalry fights a primarily naval force: nothing.

77. To this end, Aquelus built land walls to protect against an assault from the north, south, or east. He also set out defensive fortifications on the river side that included provisions for converting ships into floating barricades. Very little remains of any of these structures, as the contractor who won the bid, purportedly a former Brueghelite, used inferior materials; the extreme eastern side of the Religious Quarter still abuts the last nub of the land walls.

78. Even if there had been no famine, Aquelus would have been obliged to take nearly as many ships with him, for they would have to pass through the outer edge of Brueghelite waters in order to hunt the squid.

79. Aquelus’ one weakness was a penchant for taking personal command of military expeditions. Such bravery often helped him win the day, but it would also be the cause of his death a few days shy of his 67th birthday, when, although incapacitated as we shall see, he insisted in riding a specially-trained horse into battle against the Skamoo, who had come down from the frozen tundra to attack Morrow. Aquelus never saw the northern giant who felled him with a battle axe.

80. Note the difference between this symbol and the one accompanying footnote 23. No one has yet deciphered the original symbol, nor the meaning of its “dismemberment.”

81. Who but Sabon, of course. Sabon claims the Menites herded up the city’s residents, massacred them some fifty miles from the city, and then left behind evidence to implicate the gray caps. She supports this ridiculous theory by pointing out the Cappaness’ fate (soon to be revealed).

82. Aquelus’ lover for many years. What Irene thought of this arrangement we do not know, but we do know that she treated Nadal with much more kindness and respect than he treated her. Later, he would lose his position for it.

83. The reason for this decision appears to have been both political and personal. Although Aquelus never commented on the decision either in public or private, Nadal wrote after the Cappan’s death that (much to Nadal’s distress) the Cappan truly loved Irene and, in the madness of his grief, was convinced she still lived underground. However, Nadal’s account must be considered somewhat disingenuous, for if Aquelus believed his wife was alive, surely he would have allowed the military to send a large force after her? No, his sacrifice served several other purposes: if he did not go, then in the current state of anger and anguish, these men would surely take their own actions, possibly overthrowing him if he tried to stop them again. (Further, if his descent was seen as taken on behalf of Irene, perhaps the Menite king would look more kindly upon the Cappan.) Most importantly, Aquelus was an ardent student of history and must have known the details of the gray cap massacre and the subsequent burning of Cinsorium. No doubt he interpreted the gray caps’ actions as revenge, and what must be avoided at all costs were reprisals against them, which would only lead to further retaliation on both sides, permanently destabilizing the city and making it impossible to rule. For, if the gray caps could make 25,000 people disappear without a trace, then Aquelus had only two choices: to leave the city forever, or reach some sort of accommodation. Perhaps perceiving that, having taken their revenge, the gray caps might be persuaded to negotiate, knowing also that some action must be taken, and even now hoping against hope to rescue his wife, he must have felt he had no choice. If Aquelus saw the situation in this light, then he was among the most selfless leaders Ambergris would ever have; such selflessness would carry a heavy price.

84. In the unlikely event that you are wondering how so many ministers survived the Silence, let me draw aside the veils of ignorance: Ministers were in no way exempted from periodic military service—in fact, their positions demanded it, since Aquelus was determined to keep the army as “civilian” as possible. Therefore, at least seven major ministers or their designees had sailed with the fleet.

85. Peter Copper, in his biography Aquelus, provides a poignant account of the Cappan’s departure for the nether regions. Copper writes: “And so down he went, down into the dark, not as Manzikert I had done, for blood sport, but after much thought and in the belief that no other action could deliver his city from annihilation physical and spiritual. As the darkness swallowed him up and his footsteps became an ever fainter echo, his ministers truly believed they would never see him again.”

86. Near Baudux, where the old ruins of Alfar still stand; grouse and wild pigs are plentiful in the region.

87. At the time she meant for such help to strengthen her internal position, not to defend the city from external threats.

88. That the Cappaness even managed to have the commanders imprisoned is testimony not only to Irene’s strength of character, but to the civil service system put into place by Manzikert II. Most survivors of the Silence, when the Cappan’s decision and the rumor of the mushroom dwellers’ involvement became common knowledge, were for an all-out assault on the underground areas of the city. Indeed, despite the Cappaness’ reiteration of Aquelus’ orders, Red Martigan, a lieutenant on the Cappan’s flagship, did lead a clandestine operation against the mushroom dwellers while the Cappan was still below ground. He took some 50 men to the city’s extreme southeastern corner and entered the sewer system through an open culvert. Some days later, a friend who had not joined Martigan’s expedition went down to the culvert to check on them. He found, neatly set out across the top of the culvert, the heads of Red Martigan and his 50 men, their eyes scooped out, their mouths to a one set in a kind of “grimacy” smile that was more frightening than the sight of the heads themselves. As to whether this action on Martigan’s part hurt Aquelus’ efforts underground, I can only offer the by now familiar, and irritating, refrain of “alas, we shall never know.”

89. While we can trust Nadal on the contents of the speech, he is a less trustworthy reporter of the actual verbiage: in his mouth, even the word “nausea” becomes both vainglorious and tediously melodramatic. He is, however, our only source.

90. In reality, the Haragck were the greater threat.

91. With the result that in later years, under weak cappans, the mayor actually had equal status.

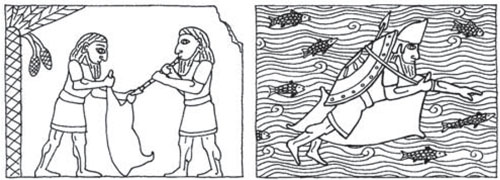

92. How did the Haragck cross over in such numbers? Atrocious swimmers, they somehow managed to make 7,000 inflatable animal skins—not, as rumor has it, made from their ponies, which they loved—and, fully armed, floated/dog paddled across the Moth. The reliefs that depict this event are among the only surviving examples of Haragck artwork:

The more perplexing question is: How did the Haragck know to attack so soon? Until recent times, it remained a mystery. Even a good rider could not have reached Ambergris’ western borders in less than three days, and it would take three days to return after receiving the news—to say nothing of crossing the Moth itself. Five years ago, a carpenter in the western city of Nysimia accidentally unearthed a series of stone tablets carved with Haragck folk legends, and among these is one, dating from the right time period, that tells of a mushroom that sprang suddenly from the ground, and from which emerged an old man who told them to attack their “eastern enemies.” Could it be that the mushroom dwellers managed to coordinate the Haragck attack with their Silence? And could the old man have been Tonsure himself?

93. Seeking to redeem themselves, some rebel Ambergrisian commanders asked to be put in charge of the dangerous street-to-street fighting, and accounted themselves well enough that although they were deprived of their rank and returned to civilian life after the emergency, their lands were not confiscated, and neither were their lives.

94. Worse still, whatever animal they had made their floats from had wide pores and the skins, hastily prepared, suffered slow leakage; although the vast majority had survived the initial crossing, many sank upon the return trip.

95. A notorious cannibal with a taste for the western tribes; that Aquelus kept him on retainer as a buffer against the Brueghelites may have been a political necessity, but it was still morally reprehensible.

96. The only reason the Haragck regrouped so quickly—they would pose a threat to Ambergris again a mere three years later—is that their great general Heckira Blgkkydks escaped the Skamoo with seven of his men and, his anger fearsome to behold (more fearsome than that of Manzikert I), eventually reached the fortress of Gelis, where the Haragck Khan Grnnck (who had ordered the amphibious attack on Ambergris) had taken refuge. Starving, shoeless, his clothes in tatters, Blgkkydks burst into the Khan’s court, reportedly roared out, “Inflatable animal skins?!”, cut off his ruler’s head with a single blow of his sword, and promptly proclaimed himself Khan; he would remain Khan for 20 years before the destruction of the Haragck as a political/cultural entity. Luckily, he spent the next three years annihilating the Skamoo, for he had suffered terribly at their hands, and by the time he refocused on Ambergris, the city had sufficiently recovered to defend itself. (One long-term effect on the Haragck as a consequence of their failed attack on Ambergris was a crucial lack of good translators, almost all of whom had been killed by the burning faggots of Ambergris. Thus, when Blgkkydks issued a formal demand for Ambergrisian surrender as a pretense for declaring war, the threat which accompanied the demand read, “I will put fried eggs up your armpits,” when the old Haragck saying should have read, “I will tear you armpit to armpit like a chicken.”)

97. Some horticulturists—none of the ones consulted for this travel guide—have pointed out that the tissue in eyeballs provides excellent nutrient value for fungi.

98. We cannot forget the late Voss Bender’s opera about the Silence, The King Underground, which—although it contains a patently idiotic wish fulfillment sequence in which the Cappan single-handedly slays two dozen midgets dressed as mushroom dwellers, after which “all quaver before him”—has a rather profound and singular beauty to it, especially in the scene where the Cappan crawls back up the steps to the surface, hears the voice of his Irene, and, his hand upon her cheek (aft, not nether), sings:

My fingers are not blind,

and they hunger still

for the sight of you;

and you, not seen but seeing,

can you bear the sight of me?

As Bender’s opera is more popular than any history book, his vision has become the popular conception of the event, conveniently ignoring the unfortunate Nadal’s passion for the Cappan. Luckily, many subjects—including the Haragck’s use of floating animal skins—Bender thought to be unsuitable for opera, and it is in such low domains, far below the public eye, that creatures such as myself are still allowed to crawl about while muttering our “expert” opinions.

99. Although the Menite king did pressure her to annex Ambergris for Morrow; already firmly committed to her adopted people, she put him off by invoking the specter of intervention by the Kalif should the Cappandom fall into Menite hands.

100. That Aquelus still loved her is undeniable, and he himself made no complaint, although many of his ministers, who effectively lost power as a result, did complain—vociferously.

101. Nadal, who had stuck by Aquelus through all of this, reports to us a conversation in which the Cappan chastised Nadal for his anger at the many slurs, saying, “They have suffered a terrible loss. If to heal they must remake me in the image of the villain, let them.”

102. It is outside the scope of this essay to tell of the continuation of the Manzikert line or of the mushroom dwellers; suffice it to say, the mushroom dwellers are still with us, while the Manzikerts exist only as a borderline religion and as a rather obnoxious model of black, beetle-like motored vehicle.

103. Little wonder that many moved away, to other cities, and that their places were taken by settlers from the southern Aan islands and, north, from Morrow. Additional bodies were drummed up amongst the tribes neighboring the city; Irene offered them jobs and reduced taxation in return for their relocation. The influx of these foreign cultures into the predominantly Aan city forever diversified and rejuvenated the local culture . . . We might well ask why so many people were willing to reinhabit a place where 25,000 souls had disappeared, but, in fact, the government deliberately spread misinformation, blaming the invading Haragck and the Brueghelites for the loss of life. In the confusion of the times, it appears many outside of the city did not even hear the real story. Others chose not to believe it, for it was not, after all, a very believable story. Thus, for several centuries, historians who should have known better promulgated false stories of plague and civil war.

104. Given the magnitude of the loss, remarkably few survivors killed themselves. We must credit the industriousness of Irene and Aquelus—the example they set and the work they provided.

105. For, at the 100-year mark, the mushroom dwellers first began to integrate themselves with Ambergrisian society, albeit as garbage collectors.

106. As recently as 50 years ago, a few homes were found in this state: they had been boarded up and then built over, and were discovered by accident during a survey expedition to install street lamps. The surveyors found the atmosphere within these rooms (the dust over everything, the plates and kitchen implements corroded, the smell dry as death, the dried flowers set out as a memorial) so oppressive that after a brief reconnaissance, they not only boarded them back up, but filled them in, despite a vigorous protest from myself and various other old farts at the Ambergrisian Historical Society.

107. If so, then the Devil has saved it several times over.

108. At this point in the narrative I begin to make my formal farewells, for those of you who ever even noticed my marginal existence. By now the blind mechanism of the story has surpassed me, and I shall jump out of its way in order to let it roll on, unimpeded by my frantic gesticulations for attention. The time-bound history is done: there is only the matter of sweeping the floors, taking out the garbage, and turning off the lights. Meanwhile, I shall retire once more to the anonymity of my little apartment overlooking the Voss Bender Memorial Square. This is the fate of historians: to fade ever more into the fabric of their history, until they no longer exist outside of it. Remember this while you navigate the afternoon crowd in the Religious Quarter, your guidebook held limply in your pudgy left hand as your right hand struggles to balance a half-pint of bitter.

109. The library already housed a number of unique manuscripts, including the anonymous Dictionary of Foreplay, Stretcher Jones’ Memories, a few sheets of palm-pulp paper with mushroom dweller scrawls on them, and 69 texts on preserving flesh, stolen from the Kalif, that had been of great use to Manzikert II while conducting his body parts shopping spree among the saints.

110. As it is, when copies were made available 50 years later, it forced Cappan Manzikert VI to abdicate and join a monastery.

111. Alas, Abrasis never commented on the consistency of the handwriting!

112. With the exception of his entry describing the massacre and Manzikert I’s decision to go underground.

113. No less a skeptic than Sabon half-heartedly documents the folktale that the Manzikert I who reappeared in the library was actually a construct, a doppelganger, created out of fungus. Although ridiculous on the face of it, we must remember how often tales of doppelgangers intertwine with the history of the mushroom dwellers.

114. Another indication Manzikert was a little man.

115. Then as now, bastards were a sel-a-dozen amongst the clergy; how much more interesting to know where this mother and child resided—Nicea, perhaps?

116. Sabon dryly writes, “Tonsure was already the most finished man in the history of the world. How then could they improve upon perfection?”

117. Most of the scribbles are erotic in nature and superfluous. Of the writings, the following lines appear in no known religious text and are accompanied by the notation “d.t.,” meaning “dictated to.” Scholars believe that the lines are an example of mushroom dweller poetry translated by Tonsure.

We are old.

We have no teeth.

We swallow what we chew.

We chew up all the swallows.

Then we excrete the swallows.

Poor swallows—they do not fly once they are out of us.

If this is indeed mushroom dweller poetry, then we must conclude that either the translator—under stress and with insufficient light—did a less than superlative job, or that the mushroom dwellers had a spectacular lack of poetic talent.

118. They’re for it, by the way.

119. Lacond’s pet theory, sneered at by Sabon: the two shall continue to make war, history itself their battlefield, hands caressing each other’s necks, legs entwined for all eternity, and yet neither shall ever win in such a subjective area as theoretical history. (Although my pet theory is that Lacond and Sabon are the conflicting sides of the same hopelessly divided historian. If only they could reach some understanding?)

120. Sabon has suggested that the mushroom dwellers had a form of zoetrope or “magic lantern” that could project images on a wall. As for the reference to a “Keeper,” it appears nowhere else in the text and thus is frustratingly enigmatic. Many a historian has ended his career dashed to pieces on the rocks of Tonsure’s journal; I refuse to follow false beacons, myself.

121. I have a certain affection for Lacond’s theory that Tonsure’s journal is merely the introduction to a vast piece of fiction/nonfiction scrawled on the walls of the underground sewer system, and that this work, if revealed to the world above ground, would utterly change our conception of the universe. Myself, I believe such a work might, at best, change our conception of Lacond—for, if it existed, at least one of his theories might be accepted by mainstream historians.

122. The most recent, 30 years ago, resulting in the loss of the entire membership of the Ambergrisian Historical Society, and two of its dog mascots.

123. Until recently you could take an ostensible tour of the mushroom dwellers’ tunnels run by a certain Guido Zardoz. After tourists had imbibed refreshments laced with hallucinogens, Zardoz would lead them down into his basement, where several dwarfs in felt hats awaited the signal to leap out from hiding and say “Boo!” Reluctantly, the district councilor shut the establishment down after an old lady from Stockton had a heart attack.

124. And since discontinued—too runny.

125. A passage from his Midnight for Munfroe reads “It was in this cloying darkness, the lights from Krotch’s house stabbing at me from beyond the grave, that I could no longer hold onto the idea that I was going to be all right. I would have to kill the bastard. I would have to do it before he did it to me. Because if he did it to me, there would be no way for me to do it to him.”

126. Certainly possible—Glaring could have interviewed any number of Truffid monks or read any number of books, few now surviving, on the subject.

127. Sabon notes that Glaring kept copies of his forgeries. Further, that a letter Glaring wrote to a friend mentions “a rather unusual memoir of sorts I’ve been told to duplicate.” Sabon believes Glaring made a true copy of the original pages. If so, no one has found this true copy.

128. It is perhaps too cruel to think of Tonsure not only struggling to express himself, to communicate, underground, but also struggling above ground to be heard as Glaring tries equally hard to snuff him out.

129. Although Sabon, predictably, claims Nadal’s eyewitness account could also have been forged by Glaring.

130. I myself have journeyed to Zamilon to see the page, and am cagey enough at this stage of my bizarre career to decline comment on its authenticity or fakery.

131. Admittedly confined to the pages of obscure history journals and religious pamphlets.

132. Then called the Morrow Religious Institute.

133. Cadimon Signal was a friend of mine and so, to avoid a conflict of interest, I shall not expound upon his many virtues—his strength of character, his fine sense of humor, the pedigree of the wines hidden in his basement.

134. The Kalif had had golden page numbers added for his convenience.

135. Signal reports that the attendant “flipped through the pages at such incredible speed that we could hardly see them. When it came time for us to present the 10 page numbers, which we simply chose at random, a great ceremony was made of taking them to the attendant, who made an equally great show of finding the right page, during which we were made to wait outside, for fear we might see a forbidden page. By the time the first page was located and presented to us some 20 minutes had elapsed, and it turned out to be blank, except for the words ‘see next page.’”

136. Suitably tall, although the statue’s torso and legs (and the horse itself—Manzikert never saw a horse, let alone rode on one) are not of Manzikert I, but the remains of an equestrian statue dating from the period of the Kalif’s brief occupation of the city—onto which someone has rather crudely attached Manzikert’s head. The original statue of Manzikert I was of an unknown height and showed Manzikert I surrounded by his beloved rats, rendered in bronze. An enterprising but none too bright bureaucrat sold the statue, sans head, for scrap to the Arch Duke of Banfours a century before the Kalif’s invasion; the Arch Duke promptly recast the statue as a cannon affectionately christened “Old Manzikert” and bombarded the stuffing out of Ambergris with it. As for the rats, they now decorate a small altar near the aqueduct, and if they look more like cats than rats, this is because the sculptor’s models died half way through the commission and he had to use his tabby to complete it.

137. Surely, after all, it is more comforting to believe that the sources on which this account is based are truthful, that this has not all, in fact, been one huge, monstrous lie? And with that pleasant thought, O Tourist, I take my leave for good.