The Political Death of Milošević

FLORIAN BIEBER

University of Graz*

Despite the continued spectacle of his trial, widely broadcast in Serbia and viewed by his supporters, Milošević’s political significance declined in Serbia after 2000. The funeral commemoration marked a brief moment when the eclectic groups of supporters converged. This chapter examines the contradiction between the “political death” of Milošević in 2000 and his revival as a “show star” during the trial in Serbia. It argues that despite the attention the trial enjoyed in Serbia, it marked the divorce between support for the politician Milošević and the narratives he helped popularize.

—FROM THE OBITUARIES, MARCH 2006

Serbia and the Socialist Party of Serbia are proud to have been led by him and that we were his contemporaries. History will never forgive us, if we give up what he fought for. For the final victory!

—SOCIALIST PARTY OF SERBIA1

For Slobodan Milošević. Thank you for all the betrayals and theft, for every drop of blood which thousands have lost because of you, for fear and uncertainty, for wasted lives and generations, dreams which were not fulfilled, for the horror and the wars, which were, without us being asked, waged in our names, for the load you placed on our shoulders.

We remember the tanks on the streets of Belgrade and the blood on its pavements.

We remember Vukovar. We remember Dubrovnik. We remember Knin and Krajina.

We remember Sarajevo. We remember Srebrenica. We remember the bombing.

We remember Kosovo.…

—NADA, SREĆKO, žIVKO, SLOBODA, VESELA, AND MILE ĆURIĆ2

On 18 March 2006 some eighty thousand people gathered in front of the Parliament of Serbia and Montenegro, as it then was, to commemorate the death of Milošević, while a few hundred meters away toward the center of town, past some Belgraders enjoying a walk on a sunny early spring day, around five hundred people released balloons to celebrate the final end to the Milošević era.3

The site of the commemoration in front of Parliament was no coincidence: It was on the same square that some half a million citizens from all over Serbia had brought the Milošević regime to its knees on 5 October 2000. On the same stage, just over two years after Milošević’s death, Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica and a cohort of fellow nationalists would commiserate over Kosovo’s declaration of independence. The mass protests in 2000 marked the end of Milošević’s regime, the commemoration in 2006 his death, and the Kosovo demonstration in 2008 the ultimate failure of his political project.

Ten years after he lost power, Milošević’s political heritage is complex: The ideas that shaped his ascent and his agenda still hold currency among intellectual and political elites, although they are no longer willing to pursue those ideas by force. At the same time, no significant political party or group harks back to the Milošević era or portrays itself as heir to his ideas or policies.

This chapter explores this apparent contradiction by discussing how and why the initially successful performance of Milošević at the ICTY did not translate into increased political support for his party or other parties with a nationalist platform. In order to examine this paradox, we will first explore the impact of the Milošević trial on the Serb audience, followed by a discussion on the decline of the fortunes of Milošević’s Socijalistička partija Srbije (Socialist Party of Serbia or SPS) and third, the consequences of Milošević’s death for politics in Serbia and for the legacy of his ideas.

When the Milošević trial began in February 2002, millions in Serbia watched their former president perform in court, speaking to them directly and seeking to justify his time in power. During the early phases of the trial, many observers worried that the process might actually backfire by revitalizing the political fortunes of Milošević and reinvigorating nationalism in Serbia.4 Did Milošević indeed become a “star” during the trial and if so, why did his popularity not translate into electoral results for his Socialist Party?

When the trial began, three TV channels in Serbia initially broadcasted the proceedings, and in the first days of the trial, their viewer numbers doubled. Half of all citizens of Serbia watched the third day of the trial, when Milošević began his opening statement, rising to nearly two-thirds watching parts of the fourth day of the trial (which took place on a holiday in Serbia).5 In response, Goran Svilanović, the FRY’s foreign minister, called the trial a “soap opera” for Serb viewers.6

However, such intense interest was not to last. As the trial dragged on with its often very technical discussion, viewer ratings declined.7 By March 2002, the month after the trial began, the state broadcaster Radio Televizija Srbije (RTS) had terminated its live broadcasts, leaving only the federal news channel YU Info and B92 to broadcast the trial. RTS reportedly made its decision due to high costs and lack of viewer interest. But critics have pointed out that the continued popularity of the broadcasts on B92 and the intense attention devoted to the trial in other media, including print, suggest these were not the real or primary considerations.8 In the first months, according to B92, some hundred thousand viewers in Belgrade watched the trial, and twice as many in the rest of Serbia.9

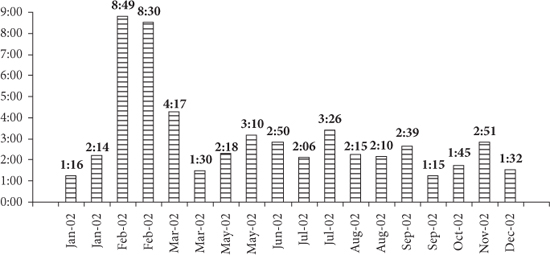

The declining interest in the trial, however, was real. Observers in Serbia suggested that the goal of educating the population about war crimes through the broadcast was not achieved.10 This decline in interest is not only reflected in lower ratings for the live broadcasts, but also in news coverage of the trial on TV and radio. After a spike during the opening of the trial in February, by the second half of March 2002 Milošević ceased to be the main topic of the electronic media (see Graph 1).* Generally, broader ICTY-related topics, such as cooperation and conditionality, received greater attention than the Milošević trial. Other topics that gained in popularity instead were the DOS government, both in terms of its reforms and the crisis between the two main parties: Zoran Đinđić’s DS, and Vojislav Koštunica’s DSS.

GRAPH 1 Time (in Hours) Devoted to Milošević in Main Evening News, 200211

In fact, the decline of the viewing numbers coincided with what Florence Hartmann, the spokesperson of the Prosecutor, suggested: the trial was no longer a “media show[.]”12

The fact that B92 remained the primary broadcaster of the trial* reflected its goal to educate viewers in Serbia about both the Tribunal itself and the past. This was also consonant with the view, then current among outside actors—including B92’s funders, that sustained media attention to the trial could have a beneficial effect in turning public opinion in Serbia away from violent nationalisms and towards confronting the past.13 Throughout the trial, however, the impact of live broadcasts remained controversial within Serbia. A number of intellectuals and journalists argued that it benefited Milošević by providing a stage, whereas others argued that the content of the trial would eventually undermine Milošević’s narrative.14

The new visibility of Milošević was in itself a change for most citizens of Serbia. Not only had he been invisible after his fall from power until the beginning of his trial, he had also maintained a relatively low profile during most of his decade in power. Although in one sense ubiquitous and omnipresent through his and his party’s control of the state, media, and public life, as a person he was not actually very present in the public eye. His interviews and speeches from the 1990s barely fill 160 pages,15 whereas his first collection of speeches, spanning the period of 1984 to 1989—that is, the period just before and during his ascent, fills more than twice as many pages.16 His decade in power had been marked by his lack of engagement with citizens—a point Prelec takes up in a rather different context—and now the trial provided Serbs with daily exposure to his ideas and worldview. This was enhanced by the fact that Milošević was not addressing the Prosecution or the judges in court, but the Serb audience at home. As Draško Tankosić, a Serb marketing analyst, remarked, “it is obvious that the people are interested and it is equally obvious from Milošević’s performance that he is addressing our public. Thus, we are his primary target audience.”17 Thus the question arises, how did his performance impact his ratings—did he succeed in reshaping his image in Serbia?

Although the Milošević trial managed to grab the attention of many Serbs at least during its earliest phase, did this attention translate into a reassessment of the former president in Serbia? Before the beginning of the trial, Milošević’s ratings had reached rock bottom. Neither his arrest in April 2001 nor his transfer to the ICTY in June did anything to improve his popularity.18 Although the transfer was doubtless unpopular with most Serbs, and polls indicate that the Tribunal is perceived by a majority of Serbia’s citizens as a political institution, a majority of citizens still also accepted cooperation with the ICTY as a necessary evil to avoid sanctions and advance toward EU accession.19 Furthermore, during the immediate aftermath of 5 October 2000, memories of the Milošević era were still fresh, and most citizens felt Milošević should be tried, even if they preferred that it be for crimes he had committed against Serbs themselves.20 And finally, during the first year after its fall from power, the SPS had little access to media to promote its view of events.

All of these factors resulted in a precipitous decline in Milošević’s popularity right after his fall: in October 2000, only 14 percent had a positive view of Milošević, a rate that dropped to 9 percent by June 2001.21 Milošević’s popularity rating remained at this low level until 2002. Milošević, together with Vojislav Šešelj and Vuk Drašković, was one of the least popular political personalities in Serbia. The most significant shift by 2002 was not the increase in popularity for Milošević, but the continuous decline of the popularity of many of the DOS politicians who had replaced him in power.*

Milošević’s low ratings improved as part of a broader change in the political climate after 2003. The rise of nationalist media such as Kurir, Nacional, and TV Most in 2002–03 gave a greater voice not just to SPS, but also to nationalist intellectuals and commentators. The trial contributed to the change of climate: An early poll after the beginning of the trial published in the weekly NIN suggests that 41.6 percent of those polled gave Milošević a rating of five out of five for his performance.22 Similarly, a survey by the polling agency Strategic Marketing suggested that Milošević’s rating increased during the beginning of the trial in early 2002, stabilizing at a slightly higher level than before. Another increase came right before the assassination of Zoran Đinđić in early 2003, but Milošević’s ratings dropped sharply after the assassination and during the subsequent state of emergency and police Operation Sablja (Sword).23 The temporary rise of Milošević’s popularity coincided with the large media attention to his trial, but as the media coverage waned, so did his popularity boost.24

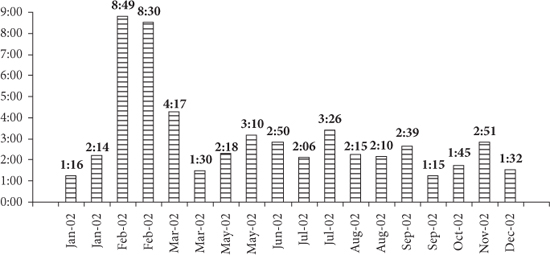

From the end of the police Operation Sablja until the end of the trial—that is, from the end of the prosecution case and throughout most of the defense phase, Milošević’s rankings varied greatly, from a low in July 2004 to a high in February 2005, though at no point during this period did the defendant’s approval ratings exceed his negative ratings (see Graph 2).

This variation occurred in a context in which the ratings of most active politicians varied even more. Miroljub Labus ratings, for example, fell from a positive 1.46 rating to minus 7.03 during the period. Overall, few politicians were able to maintain consistently positive ratings, and the general decline of politicians affiliated with DOS is striking.26

GRAPH 2 Approval Ratings for Key Politicians in Serbia, 2004–200625

Milošević’s shifting ratings throughout his trial suggest two larger trends. First, his popularity increased during the first phase of the trial, lasting until the assassination of Zoran Đinđić. This increase was caused both by his performance at the trial itself, which several other authors discuss in detail, and by the increasing frustration of many voters with the performance of the new government, expressed in declining support for DOS leaders after late 2000. Nonetheless, at no point during the first year of his trial did Milošević’s ratings exceed those of key DOS figures, such as Koštunica, Đinđić, and Labus. The fact that Milošević’s popularity increased slightly prior to the Đinđić assassination can be linked to the intensive media campaign against the Đinđić government during this period, in part the result of an organized campaign to incite the murder of the prime minister,27 of which Milošević was an indirect beneficiary.

The dive in Milošević’s rating in 2003, however, was most likely a result of solidarity with Đinđić after his murder and revelations of previous crimes discovered during the state of emergency following Đinđić’s assassination, such as the discovery of the grave of Ivan Stambolić, reports of the war crimes committed by the Red Berets, and the latter’s links to organized crime. With the accession of Vojislav Koštunica and SPS support for his minority government, we can observe a period of normalization in which Milošević’s ratings no longer changed significantly, but moved from the bottom of the rankings to the midfield of Serbian politicians.

As we move from the impact of the trial on the ratings of Milošević, it is also useful to explore how his increased popularity affected—or rather failed to affect—the popularity of his political party, the SPS. The decline of the party prior to his trial, which was linked to Milošević’s own declining political fortunes, is a part of this story.

One key to understanding Milošević’s ultimate fall lies in the nature of his earlier ascent. Although his rise was rapid and the events surrounding it often dramatic and disruptive, Milošević was no revolutionary, but an insider. Milošević had never been in opposition; his rise had always been from power to a higher level of power.28 As such, he could always rely not only on the power of the party, but also on the state. The support he enjoyed as an incumbent drew on authoritarian tendencies among parts of the electorate that favored the party in power. Furthermore, patronage allowed him to secure support and buy votes, especially from employees in the public administration and state-owned enterprises.

His political appeal also favored him only in power; once out of power his support declined drastically. In the September 2000 election, the last he contested in office, the final results gave him 37 percent of the vote for president and the SPS 32 percent for the Federal Parliament. Even though the results of those elections were never fully verified, most preelection polls also gave Milošević and his party around a third of the vote.29 Within three months, in new elections following the overthrow of the Milošević regime, support for the SPS slumped to a mere 13.5 percent.30 The SPS would not surpass even this much-reduced result for another decade, whether with the name of Slobodan Milošević on its electoral list, as in 2003, or as a party ready to form a coalition with the Democratic Party, as it did in 2008.

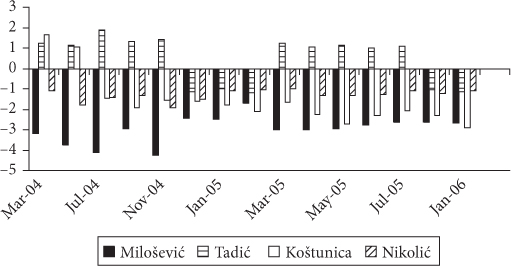

GRAPH 3 Support among Voters for SPS in Percent According to Opinion Polls (1990–2005)33

In fact, according to polling data (see Graph 3), fewer than a third of citizens who voted for Milošević in 2000 chose his party in 2003, with more of his former voters (38 percent) voting for the Srpska radikalna stranka (Serb Radical Party or SRS) instead.31 Thus, the number of voters the party was able to secure after 2000 hovered around one-fifth of the votes the party won in September 2000. Even among the voters who mostly voted for the SPS over this period, many regularly switched their support between SRS and SPS, whereas the only other party with which a significant number of SPS voters identified was the DSS.32

So why did Milošević’s fall from power in 2000 reduce the SPS to a party of single digits—and why has the party gradually broken with the Milošević legacy? There are three reasons, which are really about the political death of Milošević: demographic change, ideological incoherence, and conflict between the party and Milošević. These reasons together created a disconnection between popular support for Milošević’s narrative—expressed through the trial—and the rejection of politics based on Milošević’s agenda.

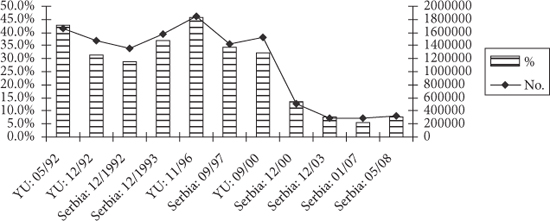

The decline of the SPS began not in 2000, but in the early 1990s—that is, when Milošević and his party were seemingly at their height. After 1992, the SPS could command the support of only a quarter to a fifth of the total electorate, resulting in election results giving the SPS between 28.8 (1992) and 45.4 percent (1997) of the vote and forcing it to rely on changing coalition partners in the 1990s (see Graph 4).34

The number of citizens strongly identifying with the party declined more during the 1990s than is reflected in election results. Although in 1993 14 percent of the electorate strongly identified with the party, this number declined to 12 percent in 1996 and 8 percent in 1998. Subsequently, even the number of those with a weak identification with the party declined, decreasing from 8 percent in 1998 to 3 percent in 2001.35

This narrowing had a demographic basis. The SPS, together with the SRS, had become a party of the losers of transition even before the transition began after 2000.36 Most workers abandoned the party after 1992, making it at first a party predominantly of farmers; later, it drew more support from citizens who did not take part in the formal work sector, such as pensioners and housewives. In particular, the party enjoyed its greatest support from older persons. In 1996, 40 percent of SPS supporters were over 60, whereas the share of the voting-age population over 60 according to the 1991 census amounted to only 23 percent; in June 2003, 57 percent of SPS voters were over 50, a category that accounted for around 45 percent of the voting-age population.37 This demographic profile made the SPS “the party of the oldest, least educated and poorest voters.”38 Such a voter profile has meant that—unlike the SRS, which was also a party of transition losers but was able to draw on younger voters—the SPS has been unable to rejuvenate itself and has remained inherently restricted in its electoral potential. By the time of Milošević’s death, SPS had become one of the two parties with the most homogenous voter base.39 It was only after Milošević’s death that the party was able to reorient itself as a center-left party and become the third largest party in the 2012 parliamentary elections with 14.7 percent of the vote (together with two smaller coalition partners).

GRAPH 4 Support for the Socialist Party in Serbian and Yugoslav elections 1992–2000.*

Thus one factor explaining the decline of the SPS has been its restricted and shrinking electoral base; even before Milošević’s fall, it had ceased to be a catchall party able to secure electoral support among all or at least most social groups. However, to understand this limitation, we need to turn to the ideology of the party and its voters, because the inability of the SPS to rejuvenate itself lay mostly with its ideological incoherence.

The homogeneity of the SPS voter base stands in contrast with the party’s heterogeneous ideological profile, and there is no agreement among Serbian political scientists how to categorize the party. Some have categorized the party as being (extreme) left-wing (as most of its voters self-identify), whereas others have called it national-conservative extremist (krajnjaši). Others have sought to square the circle of nationalism and socialism by calling the party social-nationalist.40

Although Milošević had come to power by forging an ultimately short-lived, eclectic coalition representing conflicting ideas, his party as an institution reflected only a small segment of that coalition. The contradictory streams his nationalist mobilization unified—including monarchists, communists, and those nostalgic for the SFRY; supporters of the Serbian Orthodox Church; Chetniks; and others41—could not coexist within one party. With the introduction of multiparty elections, different parties represented these streams and the Socialist Party advocated a fusion, maintaining the Yugoslav and socialist heritage, but infusing it with nationalism and antiglobalization; this ideological profile was fed by nostalgia for the previous system, but without the bratstvo i jedinstvo (brotherhood and unity) and high level of decentralization of late Yugoslavia. The fusion of left and right ideologies was common to a number of other post-Communist left-wing nationalist incumbents, but inherently narrower than the broader nationalist movement Milošević headed prior to the first multiparty elections.42

By the mid-1990s, the electorate supporting the left nationalist agenda began declining, as the electorate to which this platform appealed was disproportionally older voters and as disappointment with declining living standards and corruption made voters less likely to endorse the incumbent. Furthermore, the failure of the nationalist agenda on the battlefield in Croatia and Bosnia also undermined the party’s nationalist credentials. In response, left-wing nationalist parties such as the SPS had two choices: either to opt for a more reformist social democratic program or to promote social populism. The latter option was a successful strategy for opposition parties, not for incumbents, whereas the former was a choice SPS was unwilling or unable to engage in until 2008, due to the wars and the regional context. As a result, the SPS retained its relatively narrow ideological profile.

In many respects, the SPS became an anti-system party after 2000, in part because the party considered the events of 5 October a coup d’état. Yet at the same time, it endorsed EU integration at its sixth party congress in January 2003 and accepted privatization in principle (though it rejected post-2000 Serbian privatization).43 In addition to adopting a socialist populist line, it described liberal ideas (such as the post-2000 privatization and globalization) as “the destruction of our national identity and specificity” and singled out separatists and chauvinists—code for Kosovar Albanians and other competing nationalisms in the region—as its enemies.44 Its nationalism remained cloaked in defense against globalization, terrorism, and nationalist extremists. The party’s antiglobalist rhetoric drew on widespread opposition to the NATO intervention in 1999, and rhetoric about terrorist threats, cloaked in post 9-11 language, targeted primarily Kosovar Albanians. The SPS’ self-presentation as a party of continuity—not just with the Milošević era, but also with its nostalgia for the Yugoslav period and the Communist system45—has prevented the party from endorsing an uncompromising nationalist position, as the Radical Party did, and also made it keep its distance from the increasingly popular Serbian Orthodox Church. It was thus unable to draw on these particular national themes that gained increasing popularity, especially after Milošević’s fall from power.

The program of the party thus remained inherently transitional—between the authoritarianism of late Communism and a careful endorsement of reforms, combined with a relatively constrained nationalism articulated as defense of sovereignty. Even its social populism was unable to persuade nearly as many voters as the social populist promises of either the SRS or the Pokret snaga Srbije (Movement for the Power of Serbia or PSS) during its meteoric rise and fall in 2004–05, as it lacked a motivated base of supporters (such as the Radicals) or charismatic leaders.

Between its demographic constraints and its programmatic choices, the SPS was not only locked into low electoral outcomes, but was also unable to reform itself. Soon after Milošević’s fall, observers in Serbia had predicted—or hoped for—a transition of the SPS into a moderate social democratic force. The lack of another party on the political left, despite widespread support for left-wing policies, appeared to be an opportunity for party reform. Hope for modernization of the party was given additional impetus when the SPS lent its support to the minority government of Koštunica in March 2004.46 The return to power in 2003 of the reformed HDZ in Croatia was additionally seen as a model for the transformation of previously authoritarian parties in the region. Such a transformation was, however, difficult for the SPS.

The party’s electoral base—relatively homogeneous and less likely to have benefitted by the recent political changes—had become so radicalized that it would be unlikely to follow any reform. As late as 2007, after both Milošević’s death and the party’s support for a minority government, only 16 percent of its supporters thought that democracy was the best political system, with 29 percent making no distinction between democracy and nondemocratic regimes and 37 percent supporting the assessment that nondemocratic systems can be better in certain circumstances.47 The authoritarian and conservative profile of the voters* led to a growing rift with the leadership, which had increasingly abandoned the confrontational positions its voters held since this part of the political spectrum was covered effectively by the SRS.48 In addition, as we shall see, Milošević’s highly visible presence in The Hague proved to be an obstacle rather than an asset for the party.†

Probably the biggest obstacle to a transformation of the party was the continued political relevance of Milošević.49 The fact that his performance in court did not translate into votes was primarily the result of the increasingly difficult relations between Milošević and the party he had created.

The SPS was shaken by internal divisions in the aftermath of its fall from power; only well after Milošević’s death was the party able to regain some coherence. After October 2000, it first struggled with divisions and split-offs in the immediate aftermath of its defeat, with Zoran Lilić forming the Srpska socijaldemokratska partija (Serbian Social Democratic Party) and Milorad Vučelić the Socijalistička demokratska partija (Socialist Democratic Party). Later, in 2002, Branislav Ivković sought to take control of the SPS, but was excluded from the party and formed his Socijalistička narodna stranka (Socialist People’s Party). None of these split-offs performed well in elections, but they inevitably divided and distracted the party elites. In 2005, five out of the 22 members of the SPS’s parliamentary group broke away, accusing the party leadership of betraying the policy of Milošević.50 Already in 2002, the party leadership had come into conflict with Milošević himself after the party refused his request to endorse Vojislav Šešelj’s candidacy for the Serbian presidency and instead nominated Velimir “Bata” Živojinović.51 The efforts by the party leadership to develop an independent profile meant that the party could not fully benefit from the increase in popularity Milošević enjoyed due to his performance in court. Simultaneously, the SPS could not credibly position itself as a social-democratic party as long as it remained linked to Milošević, who opposed a move toward social democracy and closer ties to center-left parties in Europe, while the nationalist space was already taken over by the Serb Radical Party, which was more effective in mixing radical nationalism with social populism. It is this fraught relationship between Milošević and his party that partly explains why SRS was better able to attract voters dissatisfied with the post-2000 reforms than was the SPS.

Indeed, given this conflict between Milošević and the SPS, it might be more appropriate to consider the Radical Party as the main potential beneficiary of Milošević’s trial, especially considering that the SRS emerged as the largest party in early parliamentary elections in December 2003. However, the electoral victory of the SRS in the elections was not a vote for the past—in fact, the Radicals’ success can be linked to the voluntary surrender of Vojislav Šešelj to the ICTY in early 2003 and his replacement by the more moderate-sounding Tomislav Nikolić. The voters endorsed the SRS in December 2003 and in subsequent elections mostly due to dissatisfaction with contemporary reforms rather than a desire to resurrect the 1990s.52 Although it might be tempting to link the rise of the SRS in the 2003 elections* to the court case and the stage it provided for the promotion of a nationalist history of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, it is more plausible to link the rise of the SRS to domestic political dynamics in Serbia, including dissatisfaction with the outcome of economic reforms and the political infighting among former members of DOS. It is particularly noteworthy that after 2003 it was the SRS that benefited from voter dissatisfaction, not the SPS, even though Milošević formally led the party list in the December 2003 elections. In short, the success of the SRS after 2003 came not because their voters were longing for the past when the Radicals shared power with the SPS, but because they forgot this past.53 In such a context, the permanent reminder of the past that the trial became gave Milošević visibility, but did not translate into electoral gains for his party and did not clearly contribute to the rise of the SRS as the largest party in Serbia between 2003 and 2008.†

However, it is not just these three factors that undermined Milošević’s ability to experience a political revival in Serbia during his absence. The trial presented Milošević an opportunity to discuss the past, but the 1990s were a period of suffering, shortages, and war that most citizens sought to forget. Thus, although his narrative enjoyed considerable support, it was also associated with a past that was universally perceived negatively. In essence, Milošević used the trial to recite his memoirs to his former electorate. But even if the trial undeniably increased Milošević’s visibility, why would anybody want to hear his narrative considering the painful memories it evoked, and why would it have greater credibility than the other narrative presented at in the trial—that of the Prosecution?

In brief, Milošević became the spokesman for an idea: that he stood accused as representative of the Serbian nation and thus would defend not just himself, but also the nation.

In his defense strategy, as Del Ponte and other authors also show, Milošević sought to discredit witnesses of the Prosecution, in the process displaying an exceptional (and self-incriminating) knowledge of detail. He did not seek only to undermine witnesses’ credibility and their narratives, however, but also presented an alternative narrative. This narrative focused on questioning key events in the Prosecution’s chronology of the conflicts, such the killing of Albanians in the village of Račak in 1999, in order to argue that the prime responsibility for the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the crimes that admittedly occurred lay with the Western powers and their political leaders.54

Moreover, Milošević presented this not as a personal interpretation or defense, but a collective one on behalf of the Serb nation. During his opening statement, Milošević high lighted his role in this relationship:

But it is not only the Serb intelligentsia and the Academy of Arts and Sciences and the St. Vidovdan battle of Kosovo, but everybody who lent support, the government, the parliament, the various political organisations, the media. They all stand accused here. All this stands accused. The citizens stand accused, citizens who lent their massive support and elected their representatives at free party elections. We just agree on one point here, that my conduct was the expression of the will of the people.55

The fact that the Prosecution built its case on a specific set of claims about the political context, including the rise of nationalism in the 1980s and the idea of Greater Serbia, simply complemented and enhanced Milošević’s strategic choice to defend a narrative about reality, rather than himself for particular crimes.*

In addition, although its claims relied on a certain interpretation of recent Yugoslav history, the Prosecution’s overriding aim was to persuade the judges of their arguments, whereas Milošević had a different target. Thus the Prosecution may well have been more persuasive in making its case before the Chamber, but was neither able nor willing to make that case to a Serbian audience. In fact, nobody was advancing a persuasive alternative case for the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the wars in Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo—the interpretive field was in effect left to Milošević.

Besides the specific effort of Milošević to address his audience in Serbia rather than the Tribunal, other factors facilitated the greater credence Serbs gave to Milošević’s narrative than the one presented by the Prosecution. Technical aspects played their role, as Milošević spoke in Serbian, thus being directly understood by his audience whereas the Prosecution spoke in English, making their arguments accessible only through translation.* Even the structure and processes of the ICTY contributed to the rehabilitation and presentability of Milošević—a man who, after all, had become almost entirely discredited within Serbia. In an insightful analysis in Republika, Dragan Jovanov likens Milošević to Dirty Harry and notes that the very spectacle of the trial gave additional credence to Milošević and other indicted war criminals:

When you put … local gangsters, camp guards, semi-literate national ideologists, butchers, alcoholics, psychopaths dressed in expensive suits and ties into well-choreographed TV studios, encased with sophisticated professional-legal terminology and a made-up choreography—the global choreography of the world order and justice—they no longer function as a criminal gang, army and paramilitary commanders and executioners and ideological psychopaths, bearded, dirty and possessed from the TV screens in Vukovar and the hills around Sarajevo, but rather as politicians—masters with political conviction and a national and social mission.56

In light of this, it is perhaps unsurprising that the actual effect of broadcasting the trial in Serbia was to raise Milošević’s profile and encourage his much-reduced base of supporters. Indeed, it is not without irony that it was supporters of Milošević who protested when RTS interrupted its live broadcasts and who became loyal viewers of B92, which Milošević himself had sought repeatedly to close down in the 1990s.

In the domestic discourse, the newly governing parties made no concerted effort to offer a new interpretation of the 1990s. New textbooks were more preoccupied with strengthening an anti-Communist narrative critical of the Yugoslav project than with addressing the wars of the 1990s, which were glossed over.57 Other efforts to confront the public with alternative narratives of the wars of the 1990s were largely limited to initiatives by NGOs, which were, as Dragović-Soso and Pešić describe, increasingly at odds with themselves. The political elite did not fundamentally challenge the dominant perception of the conflict of the 1990s and, rather than using the ICTY to promote a debate about the past, “hijacked” transitional justice to advance individual political agendas.58

In 2005, the Milošević trial itself would provide the single most significant opportunity to challenge the narrative Milošević had been promoting in his and the Serbian nation’s defense and thereby also implicitly test the theory that intense coverage of a comprehensive and fair trial could discredit Milošević and his policies rather than provide them a sympathetic platform. This turning point in the trial, which had a clear impact on its audience in Serbia, was the screening of a video showing the execution of six Bosnian Muslim men and boys by members of the Škorpioni paramilitary unit near Srebrenica in 1995.

The video was first shown at the Milošević trial in June 2005 and rebroadcast on B92, with state television RTS showing it a few days later.59 The arrest of members of the Škorpioni, the immediate condemnation of their actions by President Tadić and his visit to Srebrenica at the anniversary of the genocide the following month triggered a brief episode of soul-searching and a complex—and apparently temporary—shift in public awareness of war crimes committed by Serbs.60

Nationalist groups attempted to minimize the impact of the video. The Radical Party released photos and videos showing war crimes against Serbs by non-Serbs, seeking to put the video into a context that was more sympathetic toward the dominant narrative.* Surveys in the aftermath of the video’s release paint a contradictory picture of its effects: Although support for the ICTY grew, one-third believed that the video was fabricated, and many felt that it obscured crimes committed against Serbs.61 Such views were given sympathetic coverage in the nationalist press, such as Kurir and Večernje novosti.62 Thus, although the video visually confronted many Serbs for the first time with war crimes, the impact on public opinion appears to have been less clear-cut.63

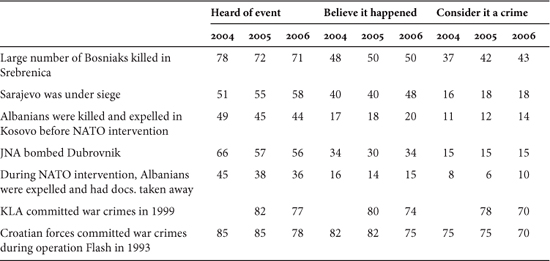

The modest impact of the video on public awareness of war crimes appears to be replicated for the Milošević trial as a whole. Although the trial brought crimes from Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo to Serbian TV screens on a nearly daily basis for over four years, Serbs’ awareness of war crimes committed by Serb forces did not increase. In fact, awareness of particular crimes committed by Serb forces, such as the siege of Vukovar, the paramilitary massacres in Bijeljina or the expulsion of Albanians from Kosovo, decreased between 2001 and 2006 (see Table 1). Only Srebrenica was more widely recognized six years after the end of the Milošević regime—possibly a consequence of the Škorpioni video, though it would be difficult to separate out the effects of the trial and video from the broader international discourse about what has become the signal crime of the Bosnian conflict. Even for the mass murder of Muslim men in Srebrenica, the increase was minimal, and only half of those surveyed acknowledged that this crime took place,64 while large numbers of Serbs continue to view themselves as less culpable for the crimes of the wars than other former Yugoslavs.† These numbers leave the sobering impression that despite the Milošević trial and numerous other efforts to discuss the disintegration of Yugoslavia after 2000, the impact has been minimal and, in Serbia at least, forgetting is stronger than remembering.

TABLE 1 Perception of Wartime Events in Serbia, 2004–200665

The four years of trial thus leave a divided impression. Although they provided a stage for Milošević to promote his interpretation of Yugoslavia’s disintegration, his party realized little political gain from this opportunity. At the same time, the trial also appears to have been unable to fundamentally change the perception and recognition of crimes committed by Serb forces during the 1990s. Despite the initial interest the trial commanded in Serbia, it became essentially a side show to the other issues that motivated voters’ choices and preferences.

The death of Milošević rendered four years of trial inconclusive and created a new martyr. After his death, the popular nationalist tabloid Kurir published a picture of Milošević under the headline “Murdered.”66 This view was echoed in the following days in nationalist tabloids in Serbia, accusing the ICTY of either directly murdering Milošević or indirectly facilitating his death. An article in Večernje novosti, for example, reminded readers that 69.56 percent of all prisoners in “the Castle of Death”—that is, the ICTY—were Serbs.67 The commemoration of Milošević’s death briefly appeared to revive the broad and eclectic coalition of supporters his party had been unable to draw upon since its fall from power. Some participants waved flags of Socialist Yugoslavia, while others carried icons. Speakers described Milošević alternatively as Christian, Serb, socialist, and Yugoslav. In the obituaries, some called him a “great Serb,” others a “dear comrade.” The Radical Party—ascendant heirs to strands of nationalism and social and populist resentment the SPS had long failed to represent effectively—lent the logistical support of its well-oiled campaign machinery. Yet the turnout at the commemoration was a disappointment. In reality, Milošević’s death was not an effective rallying call for political action, but rather an opportunity to close a chapter.

Shortly after his death, conflict broke out within the SPS over Milošević’s heritage and whether to reform the party. This conflict between the “coffin carriers”—the Milošević loyalists who carried his coffin during the funeral—and the “suitcase carriers”—a reference to a corruption scandal involving the reformist Ivica Dačić—ended with a victory for the pragmatists.68 Just two years after Milošević’s death, the SPS joined its former nemesis, the Democratic Party, in government. Similarly, the Serb Radical Party, in many aspects a more effective heir to Milošević’s policies, broke up in September 2008, with the majority and most of the leadership establishing the Srpska napredna stranka (Serb Progressive Party or SNS), which broke with the radical rhetoric of the SRS and seeks to position itself as a (relatively) moderate right-wing party. Does this then mean that, following Milošević’s political defeat in 2000 and death in 2006, his ideas have lost their political currency?

Although his unique combination of socialism with nationalism and the will to use force to pursue this agenda has certainly lost its electoral support, Milošević’s legacy lives on. This legacy is not one of a coherent national ideology (as the Prosecution during the trial sought to demonstrate), but a tension between two political visions: Yugoslavia and a Serb nation-state. The name “Yugoslavia” came to an end in 2003 with the creation of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, and three years later Serbia became an independent country, concluding a process that began in the late 1980s. In terms of domestic policies, Milošević’s regime never transformed the country into a nation-state with all the symbolic trappings—a task left to its successors. From the introduction of religious education in schools to new state symbols, the post-2000 governments have emphasized national identity more than Milošević did.

To be sure, the support of the Milošević government for redrawing the borders of Serbia to include Serbs from neighboring republics was more pronounced, at least during the early phases of the wars. The impression that the current nation-state is incomplete is still articulated by nationalist and conservative parties in Serbia, but the desire for national unity is moderated by the unwillingness to engage in open warfare to achieve these goals. This contradictory view is best embodied in the “vision” of the SNS:

The political convergence and economic unity with Republika Srpska presents a realistic policy which will, in the future, in a peaceful manner and respecting the will of the people, create the conditions for the formation of a joint or unified state of the Serbian nation and all other citizens which live on the territory of Serbia and Republika Srpska.69

Similarly, the DSS, Koštunica’s party, supports Serbian national unity in its program, even if it also supports the territorial integrity of other states in the region: “Convinced that the programmatic and national goals of our party are identical to the historical aspirations of the Serb nation, wherever it lives, we support its complete cultural, economic and spiritual unity.”70 Although less clearly articulated by other parties, this embrace of kin state policies that have a strongly territorial understanding of the relationship to Serbs outside the present state is pursued by most political parties in Serbia.*

In essence, the unresolved tension between the creation of a Serb nation-state and Yugoslavia arose from the decade-long rule of Slobodan Milošević. This legacy would have shaped the uncertainty of statehood in Serbia in the first years after his fall, irrespective of his trial. The trial appears thus not to have significantly altered the dominant discourses in Serbia about the recent past, which in itself could be seen as a success for Milošević. Neither the hopes of transitional justice advocates that the trial would force Serbs to confront the crimes committed by the Milošević regime nor their fears that Milošević’s performance would lead to a nationalist backlash materialized. After his death, many Serbs see Milošević as either a bad leader or a victim, but few share the narrative of the ICTY that he was a war criminal.71 Although political priorities in Serbia have shifted in the decade since Milošević’s fall from power, widely held perceptions about the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the wars that followed remain shaped by the narrative of Milošević.