Customs and traditions are very important to Emiratis, perhaps even more so because of the comparatively short period in which they have been catapulted into the modern age. But feasting and celebration in the past, even a generation ago, was quite different from the lavish buffet spreads enjoyed today. Materialism has become a central part of celebrations as people wish to demonstrate their generosity and treat their friends and family to the good things of the world. Of course, not everyone is enamored of this change and many, especially the elderly and more spiritually concerned, feel that the real message of these celebrations is being compromised. Behind closed doors, some Emiratis also express frustration at the erosion of their Emirati identity and the feeling they are being engulfed by a wave of Western cultural values, adopting a culture of “shop-till-you-drop” consumerism and “Friday Brunches’ (the extravagant afternoon buffets served at hotels, often accompanied by free-flowing alcohol, that are popular with Western expatriates).

A number of old Emirati traditions have been transformed and even reinvented for the modern age. Falconry and horsemanship, for example, were skills necessary for survival in a difficult environment, but have now become rather glamorous celebrations of a semi-mythical past rather different from the reality. It is quite common for societies to re-create their past so that it appears to be rather more convivial than it might really have been. For a visitor to the UAE, therefore, when it is possible to gain access to the performance of tradition, care should be taken to try to appreciate the original contours of the event.

Falconry has been an integral part of Bedouin life for centuries, so much so that the emblem of the UAE consists of a golden falcon with a disc in the middle, showing the UAE flag and seven stars representing the seven Emirates. The falcon as a totemic symbol represents force, speed, and courage, and is the inspiration behind some of the UAE’s iconic futuristic architecture, such as the UAE National Pavilion in the Dubai World Expo 2020, which takes the shape of a falcon’s wing feathers.

The sharp-eyed birds of prey can see potential victims from an enormous distance away and have proved themselves to be useful and valuable companions in the desert, as they can be trained to deliver their prey without killing it first. Sheikh Zayed developed a deep passion for falconry, which has helped the practice to flourish. It is still quite common for young Emirati men to keep a pet falcon in their homes, training them to retrieve targets flung into the far distance and to return to their arms. Falcon’s heads are usually covered with a leather hood, which is an essential aspect of training. Visitors can learn more about falconry at the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital, which is the largest falcon hospital in the world.

The UAE follows the standard Islamic calendar, although most official documents are dated using both the Islamic and Western systems. The Islamic calendar is based on the lunar cycle with twelve such months in each year, amounting to about 354 days per year. The first year of the calendar is marked by the Hijra, in which the Prophet Mohammed traveled from Mecca to Medina. This occurred, in the Western calendar, in the year 570. So the year 2018, according to the Islamic calendar, is 1439–1440 AH (After the Hijra).

In the UAE, Friday and Saturday are the weekend days off and most retail outlets and tourist attractions are closed on Friday mornings. The differing weekends causes some difficulties for organizations headquartered in a Western country, as the only days people from both countries are scheduled to work are from Monday to Thursday. When situations require urgent attention, some staff must work long hours to catch up with overseas colleagues working different time zones and days.

As Friday is considered the holiest day, it is quite common for Muslim men to attend mosque on Friday morning or lunchtime, in order to listen to a sermon from a favored imam. In other countries, such a sermon can be the starting point for a political demonstration, but this has not been the case in the UAE, partially because the contents are monitored by the authorities. The mosques’ loudspeakers broadcast Friday sermons outdoors, so if the mosque is full, those standing outside can still hear what’s being said.

It can be difficult to make holiday plans because the exact dates that religious public holidays fall are not declared until just a few days beforehand, when prices shoot up and flights book up quickly. As well as a dozen or so religious public holidays, residents also get at least one day off work to mark National Day on December 2, which commemorates the unification of the Emirates in 1971. Some Emiratis mark this joyous occasion by decking out their cars with foil artwork depicting the UAE’s leaders and flag, and showing their vehicle off in a jovial car parade which involves the prolonged tooting of car horns and spraying party string over each other. Another patriotic holiday introduced to the UAE calendar in 2015 is “Commemoration Day,” when the sacrifices of Emirati martyrs are remembered. Tributes are paid to those who died in civil, humanitarian, and military service.

Ramadan is one of the most important times of the year for Muslims, when a month of fasting during daylight hours culminates in the feast of Eid Al-Fitr. The UAE’s hotels lay on sumptuous iftar (fast-breaking) buffets over Ramadan, which are a popular way for non-Muslims to join in the festivities.

Fasting has the benefits of concentrating the mind on the spiritual sphere, as well as promoting self-discipline. During this time, which occupies the ninth month of the lunar calendar, Muslims refrain from drinking, eating, smoking, or any kind of sexual activity during daylight hours. Emiratis spend their evenings feasting with families and friends, taking turns to entertain each other.

Ramadan has a strong impact upon working life, since hours of work may be adjusted to reduce stress for those fasting. In any case, many people feel drained during the day and, consequently, their level of work and judgment may dip. Small children, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and those with medical conditions such as diabetes may waive the obligation to fast. Children are usually permitted to stay awake until late to enjoy the celebrations, which can make them fractious during the day. Many spend their daylight hours praying, reading the Koran, and snoozing. Specially made Ramadan TV dramas are watched by millions across the Arab world, and in recent years, these have explored controversial political issues.

Non-Muslims are advised that during Ramadan, they cannot eat, drink or smoke in public during daylight hours, even taking a sip of water in the comfort of their car (although feeding children in public is acceptable.) Those who drive just before sunset are warned to be cautious of the alertness of other drivers. A handful of café and restaurants in each city are permitted to stay open during daylight hours over Ramadan for the benefit of non-Muslims, so long as they black out their doors and windows. In multinational organizations, water dispensers and coffee machines are removed from sight, and most employers will provide closed rooms where non-Muslims can eat without calling attention to themselves.

This festival, which marks the end of Ramadan, is the largest and most important festival in the UAE. The streets of the UAE are lit up with twinkling Eid lights, as over the course of several days, Emiratis organize extensive feasts to entertain family and friends, assembling traditional meals of barbecued lambs and large dishes of pilaf rice. It is recommended to bless your Emirati acquaintances with Eid Mubarak during this period, which translates as “Happy Eid.”

Traditionally, Emirati women clean their homes and decorate themselves with henna and traditional perfumes. Children collect money from relatives in the neighborhood, chanting a phrase from Emirati folklore meaning “We have been given Eidiya.” Whereas this tradition used to involve small coins or sweets, nowadays it tends to be banknotes, and stores do a roaring trade in “Eid gifts.”

Emiratis also celebrate the holiday of Eid al-Adha, known as the festival of sacrifice, when Muslims recall the sacrifices made by Abraham. He was asked by God to sacrifice his own son, although once he’d demonstrated his obedience, God provided a substitute in the form of a ram. People sacrifice an animal on this day, generally a lamb, which is then used as the basis of the feast. Customarily, a third of the meat of the animal is eaten by those present, a third is given away to friends, and the remaining third is donated to the poor.

Two other holy days are the Mouloud, commemorating the birth of the Prophet Mohammed, and the Leilat al-Meiraj, his ascension into heaven upon reaching spiritual perfection.

Given that people from around the world work in the UAE, nearly every religious festival is celebrated in some form. Work schedules aren’t usually changed to cater to them—Christmas Day, for example, is usually a regular working day. But many of the less obviously religious Christmas traditions can be publicly enjoyed in the UAE by everyone—grandiose Christmas trees fill hotel lobbies, and supermarkets are stocked up with festive foods. Similarly, Diwali, which is the Hindu festival of lights, is celebrated with fireworks, light spectacles, and traditional dancing.

There are two New Year celebrations in the UAE—the start of the Islamic New Year, which varies according to the sighting of the moon, and the Western New Year on January 1. The Islamic New Year is spent with family or in prayer and contemplation, and people are increasingly using the day to make resolutions.

Family occasions such as marriages and birthdays are opportunities to reaffirm social relationships as well as occasions to celebrate.

Informal celebrations are also likely to break out in response to important sporting, social, or political events. Winning a big football game, for example, inspires a procession of beeping cars, with riders leaning out of windows waving scarves. On occasions of spontaneous celebration, those with access to Emirati women’s quarters may hear the famous ululation (a high-pitched, celebratory trilling vocal sound)

Funerals tend to be low-key and the deceased is, according to tradition, buried secretly in the desert wrapped in a simple white sheet. Funerals are not usually the occasion for the mass public gathering of relatives and friends found in other Middle Eastern societies, except on the occasion of the death of a sheikh. When Sheikh Zayed died, forty days of national mourning was declared, with government departments closing for eight days and private companies for three.

The two great traditions of Emirati society—the desert and the sea—have both inspired many legends, told and retold around campfires for generations. Common heroes include the men so generous that they sold their last few possessions to feed their guests, those who suffer the slings and arrows of fortune, like Aladdin, or the servant who is also the leader: this is a person who seems to hold a lowly position but whose wisdom and streetwise ability can guide rulers on to the desired path, offering the opportunity for glory even to the poorest individual.

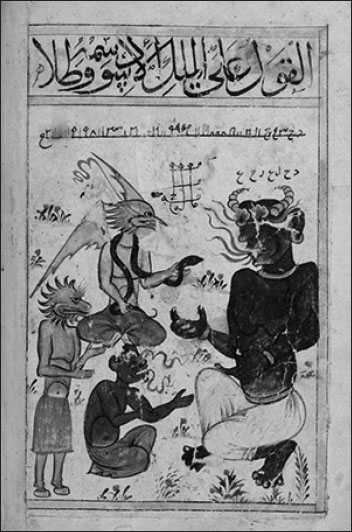

Folk wisdom in the UAE dates from the pre-Islamic period, and therefore is occasionally frowned upon when it appears to contradict Islamic beliefs. Many Emiratis particularly in rural areas still believe in the existence of djinn, which are folklore spirits that can be either good or bad, and can take the form of people we know.

The myth of djinn was immortalized on the big screen in the Hollywood movie of the same name (2013), which was filmed in Ras Al Khaimah. It was loosely based on the legend of Umm al Duwais, a murderous djinn temptress who according to one story had donkey hooves as feet and the eyes of a cat. For hundreds of years, such stories were recounted from one generation to the next but because so few were ever written down, many have been lost to the sands of time.

Because of the UAE’s coastal position and location on various trade routes, traditions from other cultures have been absorbed into Emirati heritage. Ancient Mesopotamian influences in pottery making, for example, can be seen in archaeological finds. Over the centuries, distinctive forms of cultural expression have been brought into being, including boat building, the use of folk medicine, and the creation of poetry to express ideas that are characteristically Emirati in nature. The late Sheikh Zayed observed that a country that did not know its past had neither a present nor future. Maintaining knowledge and appreciation of the past, and allowing this to guide development of society in the future, is an important charge that Sheikh Zayed laid upon his government.

Numerous museums exist to inform tourists about Emirati heritage, but for the people themselves, traditional culture is kept alive at family social gatherings and through annual heritage festivals. At the Al Dhafra Festival in Madinat Zayed, thousands flock from as far afield as Saudi Arabia for the camel beauty contests, and at the Sheikh Zayed Heritage Festival in Al Wathba, folk heritage is celebrated through traditional dancing and food. Both festivals take place in Abu Dhabi Emirate in December.

The smaller Emirates have retained more of a nostalgia for the past than the high-rise cities of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, and local heritage can be better appreciated by visiting the well-preserved forts and souks in Al Ain, and the heritage district in Sharjah.

Writing poetry is one of the most noble activities in which an Emirati man can engage. Bedouin poetry, which is known as Nabati, ranks alongside falconry in demonstrating manliness, sensitivity, and understanding of one’s cultural heritage. Neighboring Iran has, for centuries, had a tradition of epic poetry, which has perhaps helped the Bedouin spinning of tales around the campfire to become elevated into a high form of art. It would not be seemly to dwell on romantic love (and some of those who have done so have been jailed for breaching public morality), and Nabati poets try instead to reflect on their place in the universe and on matters of spirituality.

Traditional poetry is experiencing something of a resurgence in the region. Universities across the UAE also hold annual talent contests, in which the most popular contestants are almost always the poets. And millions of people from across the Middle East turn on their televisions to watch reality poetry contests, such as “Prince of Poets” and “Million’s Poets,” both of which are filmed in Abu Dhabi and based on the same formula as regional pop singing contests “Arabs Got Talent.” The prizes are worth millions of dollars, and the show also acts as a way for young Arabs to voice their feelings on contemporary issues.

In the desert communities, Al shellah is a form of chanting without the accompaniment of an instrument. It is practiced throughout the Arab Gulf, with variations from one country to another. The UAE’s shellah is mostly composed by famous Emirati poets and can be about any subject: praising the beauty of a camel, sailing, or hunting, for instance. In the past, people used to chant shellah to pass time: during desert crossings, when setting sail or, at night, around campfires; a good shellah is not just about the poetry, but also the interpretation, the vocal intonation, and how rhythmic the chanting is.

While shellah has been gradually forgotten over the last few decades, it has always been present at the Al Dhafra Festival, an annual heritage festival and camel beauty pageant that take place in Abu Dhabi’s Empty Quarter desert. During camel beauty competitions, there is a long wait for winners to be announced, which is almost always passed with outbursts of shellah, chanted loudly by a camel owner in the audience.

This distinctive dance is very different to the forms of dance commonly served up to tourists, such as belly dancing that takes place on desert safaris, or the Arabic entertainment that performed in the lobbies or restaurants of hotels. But visitors lucky enough to catch a heritage festival during their stay can get a chance to see more authentic Emirati cultural performances. The sight of rifles can cause some alarm to onlookers, and it is also customary during Emirati wedding parties for the rifles to be fired loudly into the air. But rest assured that no ill feeling is intended.

Musical instruments that are traditionally played by Emiratis include the oud (a stringed instrument played all over the Arab world), drums, tambourine (which Emiratis call the daf), rababa (a stringed instrument), and the doumbek [a goblet-shaped drum].

Another aspect of Emirati music, now almost extinct, are the songs of the Gulf Arab pearl divers. This singing, which played a key role psychologically for those men undertaking such a dangerous job, was explored and documented in the film “A Grain of Sand” (2017), by British musician Jason Carter.

Emirati dance is performed to mark the bringing together of two different tribes or families, which happens on special occasion such as Eid, engagements, and wedding parties. The most popular form of dance is the Al Ayyala (or ‘Yola’), which is practiced in north-western Oman as well as the UAE. Male dancers in white kandoras (traditional long male robe) chant poetry to the rhythmic, trance-like beat of drums, as a battle scene is simulated through dance. Two rows of about twenty men face each other, carrying thin bamboo sticks to signify spears and swords. Between the rows, musicians play drums, tambourines, and brass cymbals. The rows of men move their heads and sticks synchronously with the rhythm of the drum, and other performers move around the rows holding swords or rifles, which they throw into the sky and catch. Young girls, wearing colorful traditional dresses, stand at the front, tossing their long hair from side to side.