The UAE’s heritage and traditions are very much alive and well today, but to find them you must look beyond the skyscrapers and malls and head into the Emirati home. In Western society, parents pride themselves on raising their children to be independent and to live away from them when they reach adulthood. Conversely, in the Arab world, group identity and sense of belonging are fundamental. Emirati parents require that their children live at home until they are married, and then may even encourage their son or daughter to bring their new spouse to live with them—or at least next door.

Well-established Emirati families tend to live in large, central houses or with extended family in a compound of buildings. Privacy is paramount and homes are customarily surrounded by high walls to stop anyone looking in. Unexpected guests are frowned upon, so it is better to wait for a specific appointment. While affluent Westerners living in the UAE prefer to have villas with pools, swimming is not a popular pastime among Emirati citizens, who might instead have a traditional tent erected in their yard. Outdoor garden space isn’t highly prized, as Emiratis prefer to spend time in the shade or indoors, often with the blinds drawn. For this reason, the UAE has one of the highest rates of vitamin D deficiency in the world (over 85 percent, according to a 2016 study).

Since men and women are not generally permitted to occupy the same space, parallel facilities and rooms are built to enable men to have their own dining rooms, seating areas, and bathrooms, and women the same, depending on resources available. Children up to the age of seven are generally exempt from this restriction, and girls are introduced into segregation on their eighth birthday.

In the 1970s, it was common for Emirati families to have at least seven children. Today the average is about three, as Emiratis are tending to marry later in life. Nevertheless, this average still means that households tend to be large and busy. In the case of husbands with multiple wives, each is expected to have her own household within the larger compound and, should one have a new maid or driver, the others must receive the same. The relationships between the wives and their various children and relatives can vary considerably. The first wife is almost always Emirati, and subsequent wives are sometimes foreign. Incoming women and any accompanying family members will bring their own customs and tastes, which lend some variety to the ways in which children are raised. It is often the case that the first wife is welcomed into the fold by extended family members, and it is she who is invited to social gatherings, rather than subsequent wives and their children.

These days, Emirati children tend to live privileged lives. The concept of “spoiling” children is still a relatively foreign concept. After all, up until only fifty years ago, limited household income meant it was nearly impossible to spoil children with too many material possessions. There is also a tendency for children to be over reliant on maids, who might not have confidence or authority to discipline them. The maids are inclined to indulge children’s whims, hand out sugary treats on demand, and allow them to play video games unrestricted. These potential pitfalls are not confined to the Emirati population—plenty of expatriate parents encounter similar issues. But the issue is exacerbated in Emirati households because parents usually employ one maid per child, rather than one per family. It is not unusual for parents to have up to seven children, each with maids, plus at least one driver, all living in the same household. All this attentiveness means children can easily become overindulged.

The UAE is a safe country, and Emirati parents are usually happy to let their children play outside from a young age. Anyone driving through Emirati neighborhoods at night should keep a watchful eye out for children on the roads. Bedtime for children in Emirati culture is less strictly enforced than it is in the West.

While Western expatriate families might try to make the most of the sunshine during the day, Emiratis tend to stay indoors—a natural inclination, given that for their ancestors, shelter from the sun was essential to survival. They therefore tend to go to sleep much later, in order to make the most of the twilight hours. Nowhere is this more noticeable than in the UAE’s parks. Mornings and early afternoons are when the Westerners come out to play, as they tend to bed their children first. The Levantine Arabs come afterwards, followed in the evenings by the Emiratis, whose children will often take afternoon naps to catch up on sleep.

In the past, the Bedouin did not write things down, relying instead on an oral tradition to pass on the songs and stories of the great deeds of their forefathers. In his book Sand Huts and Salty Water, Abu Dhabi’s first schoolteacher, Ahmed Mansour M. Khateeb, describes teaching the first generation of Emirati schoolboys from the capital to read and write in the late 1950s. In recent years, the leadership has been actively encouraging its people to read, with annual book and literature festivals held in Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai. New libraries have opened across the county, and 2016 was declared “the year of reading.”

Most teachers come from overseas, and attempts made in recent years to lure more Emiratis into the teaching profession have so far been met with limited success.

Schools are generally well resourced, but teachers customarily rely for their livelihood on not upsetting the students, some of whom learn to play on this.

Long family vacations overseas are common. This leads to a broadening of experience, but as most Emirati families pull their children out of school in early June for a three month-long summer break, their schooling suffers as a result.

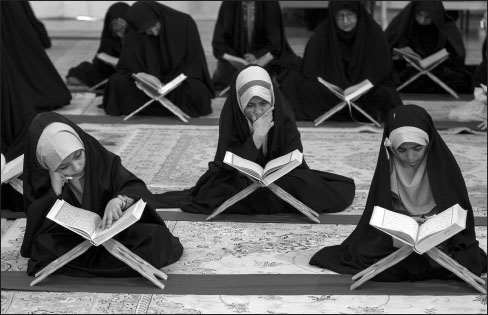

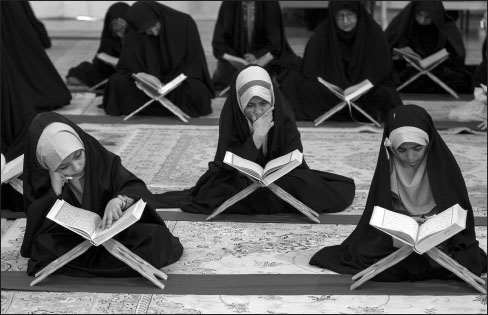

Until recently, the education system has been dominated by the rote learning approach, in which students learn by heart what teachers prescribe for them and are rewarded for repeating it verbatim. Children are also encouraged to memorize and recite the Koran as part of their education. This has changed somewhat in recent years as more creative approaches to education have been introduced. Maths and science are now taught in English, somewhat controversially. While Emiratis tend to be proficient in speaking English, many children struggle to write it, and there is also concern that their standard of written Arabic is faltering too. While in the past, Emirati children graduated from high school expecting a lucrative government job to fall into their laps, the government is now keen to impress on them that this is no longer a guarantee. Current leaders recognize that this young generation is vital to in shaping the new knowledge-based economy.

Engineering is a career held in high esteem by Emiratis, and young Emirati boys are often encouraged by their parents to pursue either engineering or business-related subjects at university. Emirati girls are now educated up to college level, and while the range of topics that they’re permitted to study has expanded, the head of the family can wield a veto in the case of debate.

Daily routine is punctuated by the five daily calls to prayer. Since Emiratis often live in suburbs on the very outskirts of town, much of their routine involves driving (or being driven) from air-conditioned cars to air-conditioned homes, or offices, and back. People often dress for a much cooler climate than that of the UAE, because they spend their whole time in an artificially cool environment.

In the past, women’s domestic work involved trips to the souk, together with food preparation and housework. Much of this has been eased by labor-saving devices and domestic help, with Emirati women supervising domestic arrangements so that they comply with their standards.

Cultural attitudes toward domestic workers are shaped by the fact that slavery endured in the Gulf much later than in other parts of the world. According to Matthew Hopper in his book Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the age of Empire, up to 800,000 slaves were transported to the Gulf in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the vast majority of whom came from East Africa. When the pearl and date markets collapsed with the global recession in the 1930s, many slaves were freed, and the UAE is now home to a sizeable proportion of black Emirati families who are the descendants of those slaves. Slavery was finally abolished by law in 1963, but until recently, the UAE’s domestic helpers, who, these days, commonly come from the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, still faced limited protection from unscrupulous employers. In 2017, this changed when a law was enacted giving domestic staff a weekly day off, thirty days of paid annual leave, the right to retain their passport, and at least twelve hours of rest each day. It is hoped that this law will stamp out cases of mistreatment, which persist in a minority of Emirati households.

Young Emirati women still conform to their societal norms by wearing black abayas to cover their bodies and shaylas over their heads. But this traditional dress has been adapted over the years to offer women avenues to express their own sense of style. Their choice of fabrics, the decoration on the hemlines, and the shoes they wear are opportunities to establish their individuality. Aspects of style that can be publicly displayed tend to be accentuated, and many young Emirati women indulge themselves with the highest, flashiest heels that money can buy, as well as stylish designer handbags, a heavily made-up face, and beautifully elaborate nail art. The market for accessories is booming in the UAE. Unlike their more conservative neighbors, the Saudi, some young ladies wear their shayla so their hair is exposed at the front. Many also wear their abayas in a way that exposes flashes of colorful garments underneath. More conservative women wear their abayas closed and a veil or burqa (mask) covering their faces, and underneath they wear a mukhawwar, which is a traditional long dress with embroidery on the chest and wrists. Emirati women visit a tailor to choose the material they like, and the mukhawwar and the abaya are cut to fit. This is usually performed by Pakistani men who are renown for their sewing skills.

Misunderstandings prevail in the West over the choice Muslim women make to wear the abaya. Historically, it was simply a light robe used to cover the body—a practical necessity in the desert sun—but not all tribes saw it as an essential piece of clothing. These days, in a country with such a large foreign population, the black abaya communicates societal status as a Gulf Arab woman, as well as signifying religious and cultural values. The Koran is somewhat vague about how exactly women should cover themselves, leaving much to interpretation, and Islamic fashion is constantly pushing the boundaries in terms of style, cut, and color.

For festive occasions, women customarily decorate their hands and feet with henna, a brown paste derived from the henna plant, which has the particular property of adhering to the skin and remaining there. While in the past, a designated older Emirati woman applied the henna to the women and girls of her tribe, today, the females tend to visit salons where specialists from other parts of the Middle East apply the designs. Left to dry, the intricate swirling patterns of the dye darken, turning from a brown outline to a vivid red-brown after a couple of days.

Visitors to the UAE might notice older Emirati women wearing a metallic-yellow face mask. This mask, known as the burqa, is traditionally worn by women across the Gulf, but in each region it has taken on a slightly different shape and style. In Dubai the burqa has a narrow top and broad, curved bottom; in Al Ain, the design features a narrow top and bottom. While the reason behind wearing the mask are to do with protecting a woman’s modesty, the burqa is also reputed to have a beautifying and whitening effect on the skin. Women who have worn the mask all their lives claim to have milky-white skin and fewer wrinkles in the area where they have worn the mask, because it shields those areas from the sun’s glare. The burqa also conveniently hides wrinkles, scars, and broken teeth. These days, the burqa has been revived as a symbol of Emirati culture because of an extremely popular television animation with Emirati children, called “Freej.” It’s about four Emirati burqa-wearing old women who live in a secluded Dubai neighborhood, trying to cope with the city’s rapid modernization.

Henna is a significant part of an Emirati woman’s wedding preparations, with the bride’s female relatives and friends hosting a henna night three days before the big event. The designs are believed to contain barakah, an unseen flow of positive energy from Allah that brings blessings to the wearer and protects against evil spirits.

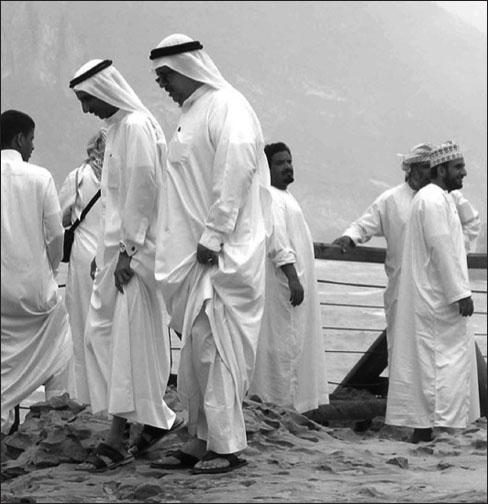

Emirati men are among the smartest-looking in the world with their immaculately trimmed beards and long, crisp and spotlessly white kanduras (gowns). At first sight, the Emirati kandura might appear the same as the Saudi, Kuwaiti, Qatari, and Omani traditional garments, but in fact they all differ slightly. The Emirati kandura is distinguished by the fact it tends not to have a collar, and usually has a long loose tassel with matching embroidery along the neckline and on the sleeves. These days, some fashionable Emirati men might distinguish themselves from the crowd by wearing a blue, brown, or black kandura, but they remain a minority.

On their heads, the men tend to wear the ghutrah. It is a square cloth, usually made of cotton, either in plain white or red with white embroidery. Young Emirati men sometimes prefer to wear baseball hats for more relaxed occasions, or may even dare to go out with no head covering at all. You might also see a man wearing a dark cloak over the kandura, known as a bisht, which is worn by royalty or important figures on ceremonial occasions.

It would be a mistake to assume that an Emirati man in traditional dress doesn’t embrace the modern world. Most are extremely well traveled, and enjoy watching the latest Hollywood and Bollywood movies, and listening to popular music on their latest Smartphones.

Friday is a day for meeting with the extended family. This enables families to reaffirm relationships through feasting, giving gifts, and generally being together, although men and women do so separately. Family occasions will generally be held in the house, but it is also increasingly common for young people to meet in restaurants and cafes. Gatherings at home tend to center on the communal meal, but there may also be singing and ululating in the women’s section, and perhaps poetry recitations among the men. The modern world has impacted upon family occasions in the UAE as elsewhere with young people preferring to be messaging friends or playing online games. Negotiation and compromise are the order of the day.

The food eaten in Emirati households has changed dramatically in the last fifty years, as the import of food from abroad has given the Emiratis a taste for international cuisine, particularly of the fast food variety. But at Friday family gatherings, traditional dishes are still enjoyed, especially Al Machboos, a blend of meat (usually mutton), rice, dried lime, saffron, and a medley of vegetables. In the past, fish was the staple diet, often served with rice and lime, and meat was regarded as a delicacy to be served on special occasions such as the birth of a baby, the event of someone managing to memorize the Koran, or the Sheikh paying a visit.

Today, the younger generation of Emirati women tend to demonstrate their culinary skills by putting traditional cooking aside in favor of baking cakes, often elaborately decorating them and posting pictures of them on Instagram. Meals are generally cooked by the domestic helper under supervision, or ordered in.

Visitors may well be curious about the rich, distinctively Arabian scent of oud in smoke that wafts from burners on perfume counters throughout the shopping malls. Oud comes in two basic forms—the resin-saturated wood, which is burnt for its rich-smelling smoke, and from distilled oil. Both forms originate from the wood of the agar tree which, if infected with a particular type of mold, produces a dark, scented resin.

In almost every Emirati home, oud in its wood form is burnt at least once a week, especially on Fridays, as a sign of hospitality to guests. As well as being burnt in the form of pieces of woodchip, oud comes in the form of bukhoor, a compressed, potent sawdust powder.

If you are invited to a gathering of women in an Emirati home, an oud burner will most likely be passed around the group, and the women will take it in turns breathe it in and waft the smoke under their abayas to absorb the rich scent into their clothes. This deeply sensual ritual is likely to be repeated throughout the evening.

Oud isn’t just burnt at social gatherings. It’s also an integral part of everyday life, as a way of getting rid of cooking smells and generally acting as an air freshener. The perfumes that are infused into the oud (which have sometimes been left to steep for as long as three months) have changed with the times, and some young Emiratis prefer a blend in which the sweeter notes of Western perfumes are added to the more traditional Arabian tones. Western luxury brands such as Gucci, Tom Ford, Dior, and Armani are targeting Arabian Gulf customers by including a touch of oud in their perfume collections. Pass any young Emirati woman and you are likely to be hit with the scent of perfume, as applying their signature perfume in liberal doses is a central aspect of their morning beauty regime.

Traditional scents that are still used today by the UAE’s traditional perfume makers include amber, sandalwood, musk, and saffron. Also popular in perfume blends is frankincense, the resin extracted from the boswellia tree that is grown in neighboring Oman. In addition to its antiseptic benefit, some Emiratis still believe it has the power to cast out djinn.

Quality oud doesn’t come cheap—a pound of oud can fetch US $20,000. One reason it is so expensive is its rarity; by some estimates, fewer than 2 percent of wild agar trees produce it. Experts claim that the very best oud comes from the oldest trees, which are even scarcer.

Applying an intoxicating perfume to both clothes and skin is an essential ritual that brides go through in preparation for their wedding, as perfume is considered to be an essential aphrodisiac in Emirati culture.