Eminent Responses

By July 1998, the framework for a Grand Strategy curriculum that would teach “across space . . . across time . . . [and] across disciplines . . . with a heavy reliance on outside presentations by practitioners”1 had gained enough momentum that Gaddis and Kennedy met with Kissinger at the Brook Club in New York in hopes of getting his blessing. They presented the class as “a long-term effort to shape the minds of future policy-makers, not as something that would have any immediate impact,” Gaddis wrote in his journal. Kissinger “immediately picked up on this theme. There was no hope of having any influence on anyone in the policy community or on the verge of entering it, he said. He mentioned, in this connection, George W. Bush, who he says is already too preoccupied with raising money to think about what he might do if he should become president.”2

Gaddis and Kennedy mentioned the NATO expansion debate as the precipitating event, but Kissinger viewed the expansion differently. He believed that Russia would never become a democracy, and that it already had too much power in NATO. But he agreed that President Clinton had bungled the expansion. “It all emphasized the importance of our initiative, we helpfully commented, and he nodded approvingly.”3

If the professors needed further proof that the Clinton administration was muddling through, they received it that fall. A team of high-ranking staff officers from NATO headquarters in Brussels spoke at Yale to make the case for expansion. During the question period, a political science professor raised his hand. Had the briefers considered how Russia would regard such a move? Perhaps enlarging NATO would undermine President Boris Yeltsin’s efforts to democratize the country, or even drive the country into a new alliance with the Chinese.

“Good God!” one of the officers exclaimed. “We’d never thought of that!”4

That reply, Gaddis would later say, “pushed Paul, Charlie, and me into thinking that, if nobody had a grand strategic perspective at such high levels, we’d better get going with what we’d only been talking about, up to that point, at Yale.”5 They’d already scheduled a weekend conference for November 1998 to tackle two questions: Could grand strategy be taught? And if so, how? Gaddis, Kennedy, and Hill invited New York Times columnist and author Thomas Friedman, a handful of people from the Brookings Institution, McKinsey & Company, and the Council on Foreign Relations, and a dozen fellow professors and graduate students from Yale and other universities, including one of the world’s foremost historians on twentieth-century Europe, Zara Steiner, from Cambridge, England. They were to meet at the Boulders Inn, a rambling, shingled, Victorian-era mansion in Litchfield County, Connecticut.

On the first night Kennedy chaired a discussion on the most successful and unsuccessful historical figures and what could be learned from the past in appraising contemporary grand strategies. It was “not too satisfactory,” Gaddis noted in his journal, “with everyone sitting around in soft armchairs dozing off after a good deal to drink and a heavy meal.”6 Those paying attention, however, got a preview of some of the underlying lessons that would later be embedded in the spring seminar. One, which comes up in the class discussion on the founding fathers, is the idea that grand strategies are forged at turning points, hammered out when leaders are under pressure. Gaddis would later quote Samuel Johnson to make this point: “Depend on it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”7

The weekend conference, according to Gaddis, picked up momentum on Saturday. He chaired a session with Friedman, an engaging thinker and speaker, whose real-world examples and focus on economics provided the right counterweight to the historical emphasis of the previous evening—and to Gaddis’s viewpoint. “Where Gaddis saw a political scene with no urgency, Friedman saw an economic scene in crisis,” one note taker at the conference wrote.8 Friedman’s main thrust was that globalization was happening quickly, and no one was minding the store: CEOs and hedge fund managers were shaping foreign policy more than the State Department.

In the afternoon Hill talked candidly—“more than I’ve heard him do,” Gaddis wrote—about his experience as a grand strategist working for Kissinger and Shultz.9

The concluding session, on Sunday morning, began with Gaddis’s depiction of what the professors saw as a destructive phenomenon in higher education: undergraduate and graduate students were being “whipsawed between the general and the particular,” he said. “There is a better way to educate them . . . we need some time to remind students of . . . what it is to have a sense of strategy—that is, how the parts to relate to the whole.”10

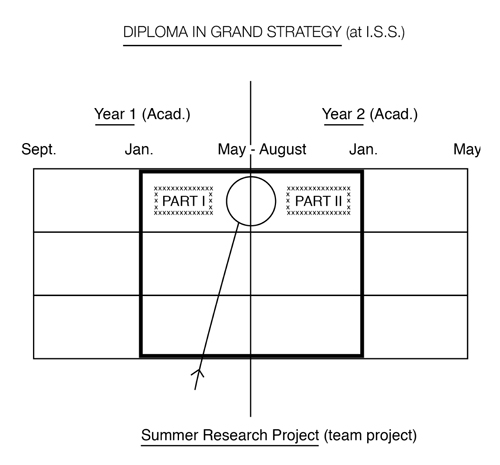

The conference culminated with Kennedy sketching out, on the back of an envelope, a yearlong program—he called it “a diploma”—in Grand Strategy. The first semester had a familiar ring: it would stress qualities of mind rather than immediate future policy, looking at the leadership styles and sets of principles that guided strategists through history. The writings of Thucydides, Clausewitz, and other classic works would be used to prepare students to deal with unknown issues. This part would be taught in the spring so that professional-school students would be free of their first- semester requirements. Despite Gaddis’s, Hill’s, and history professor Donald Kagan’s urging to include undergraduates, Kennedy’s program was designed solely for grad students. The summer would consist of individual research projects, with the fall semester set aside for student presentations. It was the first time these disparate components were linked together (the crisis simulation was added in 2002). What emerged was a course that was simultaneously old-fashioned and groundbreaking.

“I have not seen anything like it,” confirmed Peter Richardson, the president of the Smith Richardson Foundation, one of ISS’s main funders at the time.11

“It was like doing a Lego piece,” Kennedy said. “It just clicked into place. We realized we had it.”12 The professors returned to New Haven well pleased with their progress. “The whole [conference] had been intended as a preliminary consideration of the problem—does it exist? Can it be fixed? We concluded, I think, that the answer was ‘yes’ on both counts,” Gaddis noted.13

But his private musings also underscore the tentative nature of the undertaking. “Where we go from here,” Gaddis wrote, “isn’t quite clear.”14