MY PARENTS, FOR obvious reasons, stopped talking about going back to China during the occupation years, and as I became more at ease staying with the various Chinese families in the town, the subject also slipped my mind. Being cut off from my school and Green Town friends had enabled me to look at Ipoh with fresh eyes and find a sense of belonging there, as if my years growing up from eleven to fifteen helped me to think of being someone who could be called Ipoh Chinese. I was still very different from those who spoke Chinese dialects at home and practiced their popular Buddhist or Daoist faiths, but from what my imagination could make of the world of English fiction, I felt I knew who I was not. In that way, I was comfortable among the new friends I made in town, especially those who studied with me in my father’s Chinese class.

The moment the war ended, I was reminded that my family and I remained an oddity, perhaps not as odd as when we lived in Green Town because I had met other Chinese who also talked about going to China, but most planned only to visit relatives, not to go back for good. When my parents reminded me that we would be leaving as soon as we could afford the fares, I did not object. I recognized that it was what we had always wanted to do and nothing now stood in our way. As any filial son would do, I girded myself for eventual departure and reviewed my years in town in that light. I was divided between a sense of loss and the excitement of facing something fresh and new. It was clear that our going home was inevitable, and I decided to tell everyone in my school of my family’s plans.

Many of us had changed during the occupation years, and our experiences required many re-adjustments. The most obvious change for me was that I lost most of my cohort of the Standard Five class of 1941. I was one of the very few who moved up to Standard Eight in October 1945 and the youngest of the three who joined the School Leaving class in January 1946. As a result, most of those in my class of thirty-three boys were new to me. They had been in higher classes before the war and some were several years older, but fortunately they were always ready to offer help to me as the “baby” in the class.

My weakest subject was physics-with-chemistry. Our science teacher, Mr Jegadason, an Indian with a degree from the University of Madras, was conscientious, but our school had no laboratory facilities and we had to go to St Michael’s Institution in Old Town once a week to learn to do rudimentary experiments. Our mathematics instructor, Mr Ung Khek Chow, was a brilliant teacher, but I still had to ask him for extra help to understand calculus. The only area in which I could hold my own was English literature. We had a good teacher, Mr Dempsey, who made the reading and acting out of Shakespeare’s As You Like It a pleasure. He was less interested in the other prescribed texts for the Cambridge School Leaving Examinations, Joseph Conrad’s Nigger of the Narcissus and Alexander Kinglake’s Eothen. I enjoyed both books because they had me turning to the new atlas I bought to replace the one I lost during the war. It was fun looking up the exotic places those books described. They made me aware that British writers were as global as the officials and businessmen who had been exercising imperial influence in various parts of the world. Despite that, subjects like geography and history did not excite me. All I wanted to know was about what each place was best known for, not least those marked red on the map. Where history was concerned, I remember thinking that the dramatic events in Chinese history I learnt about from texts read with my father were more meaningful and memorable than the exploits of British empire-builders.

My last fifteen months in school were frantic. I had not realized how much I had missed going to school. So I wanted to be into everything. I joined the school cadet corps, and we were given wooden guns to march around the school. I tried and nearly made it onto the school team in badminton, but fared much worse in other games. I worked hard at cross-country running and was proud to come second in the finals. I succeeded in getting onto the school debating team, which won against our rivals from the King Edward VII School in Taiping. In between seeing several films each week, I also sought to follow what local workers in town were demonstrating about. On top of all that, I tried to prepare for tests in the Chinese language. That was after all a subject that I would have to sit for when I got to Nanjing. However, I did not spend enough time on my School Certificate subjects, and was fortunate to scrape by with a low Grade One result, just good enough to go to university.

In the midst of all that, my father asked me to do something that deeply touched but also saddened me. He found that most of the poems he had written over the decades had not survived the many

moves we made during the war. He decided that he should collect together the few he still had left and have them printed. The best way to do this was to use a Gestetner machine, and he asked me to

copy his poems with a stylus onto waxed stencils. He obviously thought my handwriting of formal kaishu  script was

presentable. I was very proud that he entrusted me to do that and spent many hours practicing before I began. Eventually, with painstaking care, I transcribed all his poems. He thought the results

were good enough and had the stencils printed using one of the latest Gestetner machines in town. I cannot remember how many copies were printed and bound, but he distributed them to his friends.

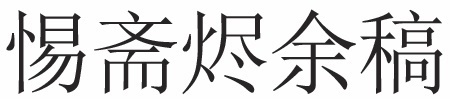

He modestly entitled the volume Tizhai jinyugao (

script was

presentable. I was very proud that he entrusted me to do that and spent many hours practicing before I began. Eventually, with painstaking care, I transcribed all his poems. He thought the results

were good enough and had the stencils printed using one of the latest Gestetner machines in town. I cannot remember how many copies were printed and bound, but he distributed them to his friends.

He modestly entitled the volume Tizhai jinyugao ( Leftover Drafts from a Respectful Studio), and opened it by saying

that he had asked his son to copy them by hand to have the poems preserved. When he died, my mother had the contents printed in a volume dedicated to him and, thirty years after

that, I had them reprinted in his memory. It deeply moved me to be so close to him, the closest I had ever been to his inner self. But it also saddens me to think that I did not fully appreciate

the sensibility and quality in his poetry and never learnt to write the kind of classical poetry that he so loved.

Leftover Drafts from a Respectful Studio), and opened it by saying

that he had asked his son to copy them by hand to have the poems preserved. When he died, my mother had the contents printed in a volume dedicated to him and, thirty years after

that, I had them reprinted in his memory. It deeply moved me to be so close to him, the closest I had ever been to his inner self. But it also saddens me to think that I did not fully appreciate

the sensibility and quality in his poetry and never learnt to write the kind of classical poetry that he so loved.

The Perak government announced it would award back pay to most of its officials, and the money my father received early in 1946 more than covered our fares to China. However, I could only take university entrance exams in China if I had completed high school. To return to China without that qualification would mean having to go to a Chinese high school and obtaining the graduating certificate there. He thought that it was more practical for me to pass the Cambridge School Leaving first and ask the Nanjing authorities to recognize it as high school equivalent, and delayed our return to China until I received the Cambridge results. The results were published in March 1947 and I obtained a Grade One pass. He immediately booked our tickets, and in June we boarded the P & O ship “Carthage” to travel to Shanghai.

I cannot recall exactly how I felt about leaving Ipoh for places I did not know, but realize it was a mixture of acceptance and uncertainty. My mother recorded her thoughts when she was in her seventies. Although they were addressed to me, I took it that she expected me to share these thoughts with my children someday. Let me end this part of the book with my mother’s words about our transition to Shanghai.

It was a smooth journey and took us only five days to reach Shanghai. Your uncles and aunts were all at the docks to meet us. We had all been through so much since we last saw one another that, when we got together, we did not know where to begin. We could only just laugh happily. Your grand-aunt had come to Shanghai for her son’s wedding and was staying at a fine residence on Avenue Joffe and we stayed with her. Your father thought his cousin’s wedding was too lavish and was unwilling to attend it. Using the excuse of having urgent matters to attend to in Nanjing, he took you with him….

I had lived in the Nanyang for a long while and my clothes were plain and old, not at all fashionable, and I had no jewellery of any kind. When I went to the wedding, I must have looked like someone from the countryside. But I went anyway, just the way I was.

That final sentiment aptly describes in a few words the way my mother was and, to me, always had been. The sentence firmly captures what returning home meant to her.