7

Highland Park Car Factory, Detroit

(1909–10)

Architecture and Work

And I saw big squat buildings with great endless windows behind which men were trapped like flies, moving but barely moving, as if they were struggling against I don’t know what impossibility. Was that Ford? And then all around and above as high as the sky, a heavy, muffled, multiple noise of torrents of machinery, hard, stubborn machinery turning, rolling, groaning, always close to breaking but never breaking.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night1

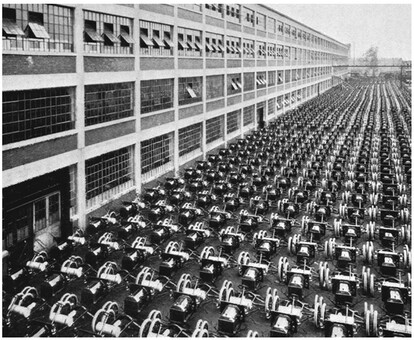

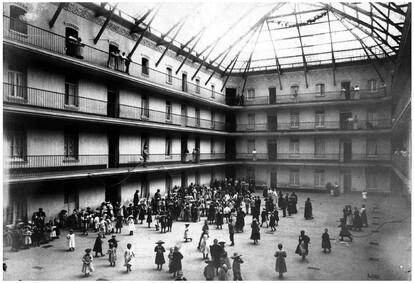

A day’s output of chassis at the Ford factory, Highland Park, August 1913

Detroit, once centre of industrial modernity – home of the production line; of Motown and techno, the music its rhythms inspired; and of that most dreamily American product, the car – lies ruined, a wasteland of abandoned buildings and vacant lots. Whole downtown blocks have been vapourised – as if the Cold War Soviets had actually hit an American target – and in their place urban farms have sprouted, offering a disturbing glimpse of the future of the West. Will we return to the land as post-industrial peasants, strip-farming among the strip malls? At its peak in the 1950s Detroit was the fourth-largest city in the States, with a population of two million, the highest national median income and the highest proportion of homeowners. Then capital abandoned the city for more easily exploited labour markets, and now only 700,000 live here, a vertiginous drop that has left vast swathes of its 140 square miles deserted, its middle classes fled or plunged into penury, and their homes foreclosed.

Many of its factories, which once churned out four of every five cars in the world for General Motors, Chrysler and Ford, have fallen silent, among them a forlorn building in the northern suburb of Highland Park. A long, plain, four-storey block, its relentless rows of dusty windows now look blankly on to the street. But it was here, just before the First World War, that two Americans – one an anti-Semitic industrialist called Henry Ford, the other an architect and rabbi’s son named Albert Kahn – came together in an unlikely partnership that changed the world. Their gargantuan factories produced one of the first mass-market cars, the Model T, but they also, as Ford himself was fond of pointing out, produced men. Ford’s aim was to change society by changing the way it worked. I’ll trace the strange journey of Ford’s ideas – from the car plant where they were born to the houses we all live in – because work doesn’t just happen in factories or offices, but also in living rooms and kitchens.

Henry Ford towered over the twentieth century that he helped to create, an indefatigable self-publicist who was hated by many but loved by a great many more. (Teddy Roosevelt, an incorrigible limelight-hogger himself, once peevishly complained that Ford’s fame eclipsed that of the presidency.) Ford’s ideas changed America and then the world, but although he became a revolutionary, he was at heart a deeply conservative man, just one of the many contradictions that characterised his strange personality.

Born on a farm during the American Civil War, he had a lasting suspicion of the metropolis, but created factories the size of cities. He loved the countryside and yet altered it for ever – automobiles meant suburbanisation. His cars helped free Americans, but his factories enslaved them. He venerated the past and yet helped dig its grave. He straddled the worlds of rural idiocy and industrial slavery, a crackpot colossus with a quenchless thirst for snake oil and an unerring instinct for the lowest common denominator (Upton Sinclair said his pronouncements were ‘shrewdly addressed to the mind of the average American, which he knew perfectly because he had had one for forty years’2). He insisted on sexual propriety in his workers but had a long affair with a much younger woman. A sentimental lover of children, he persecuted his own son even when the latter was on his deathbed. Dementedly anti-Semitic, he banned the use of brass in his factories because it was a ‘Jew metal’3 – where it was used, it was coloured black to escape his notice – and his ghostwritten ravings had a marked influence on Nazism – he was decorated by Hitler in 1938 – and yet his factories employed more black Americans than any other business, helping to create a large black middle class. Finally, he adored traditional American buildings, which he bought and shipped wholesale to his historical theme park, but his factories pitilessly dispensed with the architectural past.

Unlike the fantastic factories I described in Chapter 4 – the tobacco mosque, for example, or AEG’s turbine-factory-cum-temple, which were encrusted with status symbols borrowed from religious buildings – Albert Kahn’s contemporary plant for Ford at Highland Park was pared down to the bare minimum. This huge shed, apparently more glass than structure, was part of a new wave of workplaces known as ‘daylight factories’, which superseded the dark satanic mills of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Daylight factories employed the new invention of steel-reinforced concrete (Albert Kahn and his brother patented their own highly successful system) to open up huge apertures for glazing, whereas earlier brick structures had only been able to support a limited number of smaller windows without collapsing. Because light could now penetrate further into the interior, and because reinforced concrete could cover huge spans, factories could be made deeper and deeper, permitting production on a previously unthought-of scale.

The concrete frames that made this possible can be clearly read in the grids of Kahn’s facades, undisguised by render, paint or ornament. It wasn’t that Kahn couldn’t do historical pomposity – his domestic and public buildings are a twiddly hotchpotch of dead styles, and it must be said that the Highland Park plant’s street facade is lightly embellished – Kahn evidently thought that architectural nudity wasn’t fit for public consumption. Neither was he unconcerned about the public image of his client; indeed, the vast impersonality of his plants became a symbol of Ford’s mystique, the tabula rasa upon which he engraved his personality cult. Kahn’s austere approach was simply the last word in architectural rationalisation, with all extraneous bobbins scraped off for Fordist reasons.

Fordism (called Fordismus in Germany and Fordizatsia in Russia, a truly global phenomenon that appealed to fascists, communists and capitalists alike) is a way of thinking that has become second nature to us today but was truly revolutionary in its time. It was born of Henry Ford’s determination to reduce costs and raise wages in order to create a true mass market and a product with which to saturate it. By balancing ultra-efficient production with voracious mass consumption, Ford thought he had found a solution to one of the perpetual problems of modern capitalism – although he would never have put it so abstractly – that of overproduction. Because manufacturers constantly struggle to raise output and push down costs, including wages, there is a tendency to run out of people to sell things to (with rock-bottom wages, who can afford consumer goods?).

Ford’s solution, the popular car, was something new and controversial. His financial backers wanted him to build expensive luxury models, and thought that there would never be a mass market for automobiles. The money men abandoned him several times, and it was only on his third attempt to start a business that he found success. Consumerism was disturbing to Ford’s contemporaries, who proudly languished beneath the yoke of Victorian propriety. While patriarchs and preachers still belaboured the ears of the young with the virtue of thrift, Ford remarked to the papers, ‘No successful boy ever saved any money. They spent it as fast as they could in order to improve themselves.’4 This attitude caused uproar, but it also made Ford the richest man in the world.

In order to achieve his aim of cheap cars for all, between 1908 and 1927 Ford offered only one ultra-standardised product, the Model T, which, he famously remarked, was available in ‘any colour, as long as it’s black’. Upton Sinclair, author of a tendentious novella about Ford called The Flivver King (flivver was one of the Model T’s many nicknames), shared the popular disdain for the car’s looks:

It was an ugly enough little creation he had decided upon; with its top raised it looked like a little black box on wheels. But it had a seat to sit on, and a cover to shelter you from the rain, and an engine which would run and run, and wheels which would turn and turn. Henry proceeded upon the theory that the mass of the American people were like himself, caring very little about beauty and a great deal about use.5

In the end Ford turned out to be wrong (more about that later); nevertheless, his Model T, one of the first really affordable cars, sold fifteen million units before it was discontinued under pressure from more alluring competitors. Its plain appearance was – just like the factories that made it – the direct result of the rationalisation of the production process. The body was largely built from flat panels made in Ford’s own plants – until now car manufacturers had relied largely on parts made elsewhere – which were easy to produce and quick to assemble, so while the result was boxy, it was very cheap.

Ford, or rather his engineers, whose ideas he always claimed as his own, was forever tinkering with production, to speed it up, cut costs and maximise output. At first the factory at Highland Park was arranged in levels, with smaller parts being assembled on the upper storeys. Once complete, these passed down through holes, lifts and chutes to the first floor, where gangs of workers assembled the body at fixed stations. Eventually each finished body was lowered to the ground floor to be fitted to the chassis. Because the product and its parts were always (largely) the same, Ford could have highly specialised machines built to replace general-purpose lathes, saws and drills; these new machines also replaced skilled craftsmen, so he could employ cheaper unskilled labour. The machines and the gravitational workflow sped production up enormously, but the greatest leap forward was yet to come.

In 1913 Ford and his engineers hit on the idea of the mobile assembly line. In his own reminiscences Ford claimed to have been inspired by the swinging carcasses of Chicago’s stockyards, which moved on hooks from butcher to butcher, but his breakthrough was less the result of a momentary flash of inspiration than of an organic flow of small innovations, each leading to greater and greater speed. Turning the logic of the gravitational workflow on its side, an engine component called the flywheel magneto was moved on a conveyor belt past workers. Because the men didn’t move but the work did, all pauses in the production process were eliminated, and the time it took to make the magneto was cut from twenty minutes to five. This innovation was quickly extended to the entire production process, and by 1914 the chassis itself was being pulled along by a chain conveyor.

Previously it had taken 12 hours 38 minutes to complete an entire vehicle, but the assembly line slashed this to just 1 hour 33 minutes. The result was a breakthrough five-hundred-dollar car and a radical transformation of the way people worked. To make such cheap cars profitably, the 15,000 men at Highland Park had to produce 1,400 cars a day, eventually accounting for 50 per cent of the cars made in the world. Each man on the line was given smaller and smaller parts of the car to complete, until he reached the pinnacle (or nadir) of specialisation, reduced to a cog in a giant machine, condemned to endlessly repeat the same limited actions. This clearly dehumanising process was defended by Ford, who airily opined, ‘The average worker, I am sorry to say, wants a job in which he does not have to put forth much physical exertion – above all, he wants a job in which he does not have to think.’ But this was a case of do as I say, not do as I do. Ford admitted on another occasion, ‘Repetitive labour – the doing of one thing over and over and always in the same way – is a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind. It is terrifying to me.’6

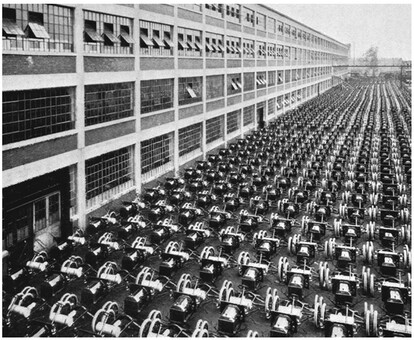

Complex actions were photographically dissected in Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s ‘motion studies’: in long exposures small lights were attached to subjects’ hands in order to record actions, with the subjects themselves reduced to faceless blurs

These ‘terrifying’ innovations were part of a new approach to work that developed around the turn of the twentieth century, pioneered by Ford, Frederick Winslow Taylor, whose systematic analysis and reorganisation of labour processes became known as Taylorism, and husband and wife team Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, inventors of the motion study. Ford claimed never to have read the work of Taylor (credibly enough – he wasn’t keen on books), but although there were differences in their approaches they shared the view that production could be optimised by dissecting the work process. The division of labour had been a central feature of the Industrial Revolution since the eighteenth century, but scientific management – as it became known – took this to its ultimate limit. By reducing the motion of the body to its smallest constituent parts, all ‘useless’ or ‘unproductive’ actions could be eliminated, thus speeding up production and maximising profit. Unlike earlier phases of manufacturing, which split the production process between workers, scientific management divided the workers themselves: each individual was no longer a whole, but a complex of motions that could be taken apart and put back together like components of a machine. The new architecture of the factory line was a Frankenstein’s lab in which humans were destroyed and reassembled to twitch like galvanic frogs in time with the speeding belt. French novelist Louis Ferdinand Céline, who visited Detroit in the 1920s, described the sensory assault of the factory, which remade men, but not in the paternalistic sense Ford had in mind:

Everything shook in the immense building, and you, too, from the soles of your feet right up to your ears, gripped by the vibration that came from the window panes and the floor and the machinery, the jolting, vibrated from top to bottom. It turned you into a machine yourself, overwhelmed, every ounce of flesh quivering in the furious howl which filled and surrounded your head, and then, lower down, churned your insides and mounted back up to your eyes in little jolts, abrupt, numberless, relentless.[. . .] When at six o’clock everything stops, the noise stays with you, and it stayed with me throughout the night – the noise, and the smell of oil, just as if I’d been given a new nose and a new brain forever. It was as if by yielding, little by little, I became someone else – a new Ferdinand.7

Apart from fragmenting labour and labourers, the invention of the moving production line also laid the way for the dreaded ‘speed-up’. It soon dawned on Ford and his managers that in order to increase profits, the conveyor needed only to whizz by a little faster. This generated its own mean logic: those men who could not keep up were fired, and supervisors, always on hand with their stopwatches to measure the minimum time in which an action could be completed, whether screwing on a nut, welding a panel or completing an entire car, were forever revising down their timings so that every man had to work as fast as the fastest man on his best day. The factory as reconceived by Kahn and Ford had become a machine for squeezing the maximum profit from the workers inside.

Ford’s plants facilitated his rationalising mania. The buildings had to be as cheap as possible – even historian Reyner Banham, an enthusiastic fan of industrial architecture, speaks of ‘an air of grudging meanness’ about Kahn’s early plants – while providing the optimum conditions for Fordist production. This meant wide-open spaces, uninterrupted by pillars or walls, to accommodate bulky machinery and a huge workforce (and to allow every action of the workers to be minutely supervised), plenty of daylight streaming through wide windows and, perhaps most importantly of all, the potential for almost infinite reconfiguration. Like Trotsky and Mao, Henry Ford believed in permanent revolution. His engineers were always coming up with new and improved layouts for the production line, and this meant that the architecture had to be open to change too.

Kahn’s building at Highland Park, with its expansive open-plan interiors, allowed this to a certain extent, but within four years of its completion it was obsolete. The birth of the moving assembly line had necessitated a new factory form. Instead of multiple storeys and the gravitational flow of ever-larger components to the finished car on the ground floor, the new building needed to be long and low in order to accommodate the lateral progress of the conveyor, and infinitely extendable in any direction, which made the increasingly built-up suburban setting of Highland Park inadequate too. The limitations of Highland Park become clear in a photo of 1914: a sloping wooden platform has been stuck to the exterior wall so that car bodies can slide down onto the chassis emerging from the building on the ground floor. The ever-expanding process has begun to send out tentacles beyond the building, an expansion that would culminate in a world empire of production and distribution, from a rubber plantation called Fordlandia in the Amazon to dealerships in England. Perhaps more than anything else, it was the contingency of Ford’s buildings – his and Kahn’s reconception of architecture as a process rather than something fixed and eternal – that marks them out as new. No longer borrowing the artifice of eternity from ancient temples and mosques, these workplaces are channels for a shifting system of flows.

In order to accommodate this conception of production, Ford and Kahn began work on a new site in the countryside west of Detroit, next to the River Rouge. The Rouge, as the plant was known, began as a shipbuilding factory during the First World War – which Ford, a lifelong pacifist, opposed bitterly, until he decided to profit from it instead. Converted to tractor and then car production after the war, the plant expanded as vast new buildings were added to the complex. Because these were single-storey with huge areas of glass – including glazed roofs, which meant that daylight could penetrate buildings however broad – reinforced concrete was abandoned in favour of lightweight steel frames, even cheaper and quicker to erect.

The Foundry Building was added in 1921, the Glass Plant in 1922 (Ford was the only carmaker to produce its own glass), the Cement Plant in 1923, the Power House and Open Hearth Building in 1925, the Tire Plant in 1931 (which used rubber from Ford’s Amazonian plantation), and in 1939 the Press Shop, an enormous L-shaped building – one leg of which was 505 metres long, the other 285 metres – where body panels were cut and moulded. At its peak in the 1930s the Rouge complex was the size of a city: it covered two square miles, employed 100,000 workers and produced 4,000 cars a day. Raw materials were shipped in from Ford’s mines via a specially dug canal, and within 28 hours had been transmuted into a car dispatched via a dedicated railway: ‘From ore to auto’, so the slogan went. This was the first vertically integrated operation in the world and perhaps the most complete example of vertical integration ever. Meanwhile, Ford’s reach, which had spread to encompass a world empire of suppliers and distributors, also began to infiltrate the domestic sphere of his workers.

Ford’s home invasion was a response to the discovery that the assembly line, though fast, wasn’t quite as fast as he had hoped. The rationalised production process turned out to have one crucial flaw: workers, made of flesh and wayward thoughts, were not as dependable or obedient as machines. Ford had degraded labour, stripping it of all self-direction and creativity, but his factories brought together these degraded workers in their thousands, facilitating organisation against his methods. Resistance was inevitable. ‘Soldiering’ – the intentional slowing down of work – was rife, and absenteeism chronic (10 per cent in 1913). The working conditions meant he couldn’t keep staff either: turnover reached an incredible rate of 370 per cent per year, which meant that in 1913 he had to hire 52,000 people to sustain a staff of 14,000. Beyond these individual forms of protest, there was also a growing clamour for unionisation, which Ford bitterly opposed.

So in 1914 Ford took a decision that set the industrial world reeling and sent his popularity through the roof: he doubled his workers’ pay to the famous five-dollar day. The newspapers reacted hysterically, with headlines like ‘World’s Economic History has Nothing to Equal Ford Plan’, ‘New Industrial Era is Marked by Ford’s Shares to Labourers’, and ‘Crazy Ford, They Called Him, Now He’s to Give Away Millions’. Within a week the company had received 40,000 job applications, and twenty-four hours after his announcement a crowd of 10,000 desperate job seekers had gathered outside the Highland Park plant – in the end they were dispersed by riot police.

What was not immediately apparent was that the five-dollar day was not the simple profit-sharing scheme Ford portrayed it as. Not all workers would get it: they first had to prove themselves worthy. In order to sort the wheat from the chaff, Ford set up the Orwellian-sounding Sociological Department, which at its peak employed fifty investigators. These clipboard-wielding spies visited employees in their homes to make sure that they complied with Ford’s commandments: thou shalt not live in sin; thou shalt not live in squalor; thou shalt not take in boarders (who might indulge in inappropriate relations); thou shalt not drink (Ford was a vociferous teetotaller) – and to dictate improvements, both moral and architectural. The aim was to produce a diligent, healthy, upstanding workforce with an insatiable appetite for consumer goods, and the money, unfrittered on booze and gambling, to buy them with.

Ford’s paternalism was not entirely unprecedented: earlier workers’ settlements established by British industrialists of a ‘philanthropic’ bent, such as the Cadbury workers’ village Bourneville, were often publess and chapel-filled, reflecting the dour religiosity of their founders. What was new was the degree of organisation and intrusiveness that Ford brought to bear on his experiment in social engineering, and the degree of hypocrisy, for Ford, though insisting on sexual propriety in his workers, was involved in a decades-long extramarital affair with a woman thirty years his junior. The extension of surveillance into the home continued the expansionary logic of the Fordist system. From workplace to bedroom – from ore to whore, one might say – the system demanded control over every aspect of the production process, now expanded to incorporate consumption; his workers had to be able to buy his cars, or the project would fall flat. The home had become part of the factory and was – just as much as a glass or tyre plant, a steel press or an iron foundry – a site of production, reconceived as a total process, and thus also subject to the improvements of scientific management.

But Ford’s imperial troops eventually retreated from the battlefield of the home. In 1921 he gave up on social engineering and shut down the Sociological Department. Continuing demands for unionisation had embittered Ford. He would not countenance bargaining with his employees and felt that his five-dollar munificence was going unappreciated. That year he instituted a speed-up that squeezed the same output from 40 per cent fewer workers, which allowed him to sack 20,000 men, including 75 per cent of his middle managers. As a result, his profits for 1921–2 jumped to $200 million. At the same time his attitude towards discipline hardened, and he turned from carrot to stick.

The man wielding that stick was Harry Bennett, an ex-prizefighter with underworld connections. Ford tasked Bennett – already head of human resources – with setting up the Sociological Department’s successor body, the Service Department. Composed of thugs, ex-cons and former athletes, this was a private army of spies and enforcers, constantly on the lookout for signs of unionisation and underperformance, given free rein to bully, harass and fire employees. After the crash of 1929, when there was increased pressure from above to cut wages and staff numbers and an endless number of desperate men willing to work for any money in whatever conditions, the Service Department instigated a reign of terror. Ford employees were arbitrarily beaten while queuing to receive their pay, talking was forbidden, visits to the toilet were only permitted when cover was available, and breaks were reduced to a fifteen-minute lunch. Bennett’s men tolerated absolutely no perceived transgressions: one worker was fired for wiping grease off his arms, another for buying a chocolate bar while on an errand, and another for smiling on duty. Ford himself behaved increasingly erratically, setting his managers against one another, undermining the authority of his own son – a president at the company – and taking his approach to organisation to Maoist extremes. In his quest for total control whole departments would be wiped out overnight, and formerly powerful executives could turn up to work to find that the boss had smashed up their desks with an axe.

It was around this time that Ford also developed a passion for folk dancing.

But in 1937 Ford’s attempt to crush the unions backfired horribly. Workers on their way to distribute a pamphlet titled ‘Unionism, not Fordism’ at the Rouge were stopped by Harry Bennett’s thugs and violently assaulted. Unfortunately for Ford, several journalists and photographers were also present at the scene, and despite the Service Department’s best efforts to beat them into submission and destroy their cameras, some photographs of what was dubbed the Battle of the Overpass made it into the papers. The result was a national scandal, with many placing the blame for the violence squarely on Henry Ford himself. Public support for the United Automobile Workers union surged, and in the end a broken and enfeebled Ford was compelled to accept unionisation at his plants. In later years he subsided into cantankerous senility, his triumphs obscured by a thickening fog of bad decisions and declining success. But although Ford, in closing the Sociological Department, had withdrawn from the domestic realm, his ideas and those of the other scientific managers had a powerful afterlife in America and Europe, bringing rationalisation into private lives and blurring the line between work and rest.

The most visible – and most unexpected – results of Ford’s project developed across the Atlantic. Kahn’s spare and clean sheds had an enormous influence on European modernists, who saw America as a ‘concrete Atlantis’, in Reyner Banham’s pregnant phrase: an actually existing land of mythical grandeur, where geometric forms as solid and pure as the pyramids pointed to an heroic new way of life. American industrial buildings were latched on to by young European architects because they heralded a future of white-hot technology, but in their hands factories became homes. The publication of the Deutscher Werkbund annual of 1913 was a seminal moment. In this book Walter Gropius, future head of the Bauhaus school of art and design, published fourteen mysterious and somewhat doctored photographs that would have an enormous impact on avant-gardists across Europe. One image showed the towering cylinders of grain elevators in Buffalo, another a tall unfinished warehouse in Cincinnati; Kahn’s glazed shed at Highland Park was included too.

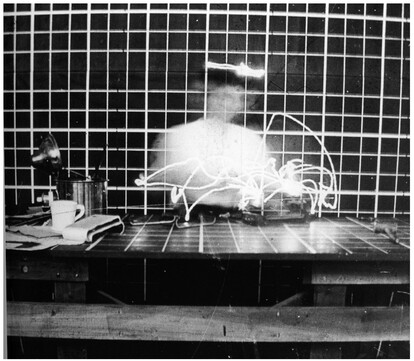

These postcards from the future were reprinted in many other works, including Le Corbusier’s famous Towards an Architecture of 1923 (Le Corbusier doctored the prints yet more to make the buildings look even ‘purer’), and they became touchstones of Americanismus – the 1920s fascination with all things transatlantic. But Europe had a long way to go before it caught up with American technology and the prosperity it promised. When he published the pictures Gropius himself was building a factory in Germany which had adopted this American look but not the techniques behind it. For decades historians assumed that Gropius’s famous Faguswerk, a factory in the Ruhr, was steel-framed. It certainly looks it: the extensive glazing bends audaciously around corners to reveal the absence of load-bearing piers. However, more recent research has revealed that this is only a trick: the brick ‘infill’, carefully recessed between the windows, is what actually holds the building up. Trick or not, this structure helped usher in a craze for the industrial aesthetic. So too did Le Corbusier’s faux-industrial villas – also made of brick. Le Corbusier chose to carefully render his walls, painting them white to achieve the appearance of concrete. He said he wanted houses to be made ‘on the same principles as the Ford car’, and proposed a mass-produced system of reinforced concrete construction. War-ravaged Europe was suffering an unprecedented housing crisis, and industrial prefabrication offered hope of homes for all. This hope turned out to be unjustified, but if houses couldn’t yet be made that way, they could at least be made to look that way.

Real and illusory high-tech Americanismus: a Mercedes advertisement shot outside Le Corbusier’s brick and stucco house for the Werkbund exhibition, Stuttgart (1927)

Albert Kahn, however, did not share the modernists’ enthusiasm for the industrial look:

I can see a very close analogy between the modern industrial building and the modern box-like, flat-roofed house, so many of which are erected today. At that, while I admire many of the modern factories, I can’t say as much for many of these houses. Indeed, much already done and being done under so-called Modernism, is to me extremely ugly and monotonous.8

Kahn, despite running one of the biggest architectural practices in the world – in 1929 he was producing one million dollars’ worth of new buildings a week – was self-effacing to the point of anonymity. In his public pronouncements he constantly attributed the genesis of his own buildings to ‘Mr Ford’s ideas’ and proclaimed architecture to be ‘90 per cent business, 10 per cent art’. He had rearranged his own practice as a production line years before he began working for Ford, turning the traditional craft-based atelier of the genius architect into a collaborative and highly rationalised plan factory. Vertical integration, via the combination in one office of 400 designers, draughtsmen, clerical staff and mechanical and structural engineers (Kahn’s was one of the first firms of architects to directly employ engineers), and the organisation of these specialists into project teams, allowed the streamlined production of an enormous quantity of industrial buildings – among them over 1,000 structures for Ford, 127 for General Motors, 521 factories in the USSR and numerous domestic and public buildings. So it is unsurprising that Kahn – who criticised ‘temperamental prima donnas’ – disliked Le Corbusier’s ‘notoriety-seeking’ and ‘inexplicable’ buildings. For Kahn (and Ford) architectural simplicity was suitable for the workplace, where economy was king, but in the domestic realm, suffused with traditional values, older styles were more appropriate – and necessary to disguise the economic realities of the home in a Fordist age. This horses-for-courses approach was true functionalism in Kahn’s estimation.

However, apart from the adoption of the ‘purity’ of Kahn’s industrial architecture for the external appearance of modernist houses, there was a deeper Fordist transformation of domestic life itself: the revolution that Ford had unleashed could not be escaped by a retreat into historical fantasy. In fact American theorists had been applying the ideas of scientific management to the home for years before Ford. The pioneering writer Catharine Beecher had first advocated a rational reorganisation of the kitchen in 1842, so one could argue, turning the conventional narrative on its head, that scientific management actually began in the home rather than the workplace. Chicken-and-egg questions aside, these attempts to reform the home and the factory demonstrate that traditional boundaries between labour and rest, home and workplace were blurring. Working-class homes, which had traditionally been sites of production (where goods were handcrafted), were now privatised as their residents went to work in factories – although as ever they remained places of work for women, who now had the double burden of factory labour and housework. Wealthier homes on the other hand had always been separated into domestic space for the owner and workspace for the staff, but as servants became unaffordable and middle-class women turned into domestic labourers, the working areas of the home attracted the attention of taste makers and reformers: enter Beecher, with her ergonomically designed kitchen.

Despite America’s early lead in sorting out the home for the middle-class housewife, it was in Europe that these rationalising ideas really took off, albeit with a distinctly different political slant. Christine Frederick’s enormously influential treatise The New Housekeeping, published in the States in 1913 and translated into German in 1921, had asked, ‘If the principles of efficiency can be successfully carried out in every kind of shop, factory, and business, why couldn’t they be carried out equally well in the home?’ This question was eagerly taken up by a number of European architects, including Austrian Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Lihotzky was a political radical who later joined the Austrian Resistance and was imprisoned for five years by the Nazis as a result. One of the first female architects in Vienna, in her early career she was involved in the creation of leftist settlements on the outskirts of that city, and later in the building of workers’ flats. This attracted the attention of German architect Ernst May, who hired her in 1926 to help reconstruct Frankfurt – which was desperately short of housing – along socialist principles. Within five years he and his team had built a ‘New Frankfurt’ of 15,000 flats, the majority of them for workers.

Lihotzky created her revolutionary Frankfurt Kitchen for these new homes. A good Marxist, Lihotzky saw the home as a site of production and women’s confinement there as an impediment to their education, employment and political engagement. She was also a devotee of scientific management, and by conducting time-and-motion studies of women at work, she reorganised the kitchen to cut out wasted movement and optimise food production workflow, thus giving women time (she hoped) to take part in more politically and economically significant activities. Taking her inspiration from the kitchens of trains, the floor space of the Frankfurt Kitchen was long and narrow, the worktops were flush, the cupboards carefully placed, and the sink, bin, drying rack and oven all arranged to create an easy-to-clean assembly line for housework.

But Lihotzky also translated another, more problematic element of Taylorism into her Frankfurt Kitchen. One of the major aims of housing reformers at the time was to separate working-class kitchens from living spaces, up to now united as Wohnküche –‘living kitchens’. They had the best of intentions in doing so: they wanted to make the home more hygienic and safe, and to dignify the labour of women by giving them a proper workplace of their own – a factory for food. However, many female New Frankfurters disliked the isolation of their new kitchens. They were separated from the life of the family and trapped in a tiny space – small for efficiency’s sake, but too small for company or supervising children. The very fittedness of these first fitted kitchens also deprived their users of the opportunity to personalise their surroundings, and many women complained that they missed their old-fashioned living kitchens.

Like Ford’s factories, the Frankfurt Kitchen was an attempt to remake the workplace rationally, and to remake people as fitter, happier and more productive. But, just like Ford, Lihotzky ignored the texture of everyday life, thus whittling away at the things that made work bearable or interesting. Lihotzky also left fundamental questions about gender roles unasked, reinforcing the idea that housework is just for women. However, these were not the first attempts to solve the problem of the relation of the two worlds of rest and work, home and factory in the industrial era. Some had taken a more holistic approach towards this question, taking into account the fine grain of human experience, our individual quirks, our need for variety – and our need for pleasure.

Born in 1772 in France, Charles Fourier worked for a long time but without a great deal of success as a travelling salesman. First-hand experience of the scams, waste and unfairness of the early industrial world and of the violence of the French Revolution (in which he lost his inheritance) led him to vilify what he contemptuously referred to as ‘civilisation’. Inspired by his commercial background and the example of Newton, he compiled a minute and slightly deranged (or is it deviously satirical?) catalogue of civilisation’s many failures and hypocrisies, including thirty-six varieties of bankruptcy and seventy-six kinds of cuckoldry. His solution was to propose the voluntary formation of communities – ‘phalanxes’– which would allow their members to share and thus reduce the burden of ‘civilised labour, which, far from offering any allurement either to the senses or the soul, is only a double torment’.9 A pioneering feminist, he included the problem of domestic labour in his calculations. He saw housework as an insurmountable obstacle to happiness, since it trapped women in a routine of idiotic and unrewarding drudgery. Arguing that, ‘Social progress . . . [is] brought about by virtue of the progress of women toward liberty,’10 he suggested that domestic labour be centralised and shared. In order to allow the burden of work to be spread equally and fairly, Fourier proclaimed that the ideal phalanx would comprise 1,620 members, a number corresponding exactly to the full range of human types according to his baroquely complex schema, so allowing for the perfect combination of varying characters and talents.

The buildings in which this new way of living would flourish were called phalansteries. In his bizarre writings (he asserted that the sea would one day turn into lemonade, and that people would reach heights of seven feet and live for 144 years) Fourier described these structures in great detail: ‘Instead of the chaos of little houses which rival each other in filth and ugliness in our towns, a Phalanx constructs for itself a building as perfect as the terrain permits.’11 At the centre of this grand structure there would be meeting rooms, libraries, educational facilities and concert halls, all supplied with water pipes, central heating, ventilation and gaslight. These spaces were to be united to the workshops and residential quarters, which would be apportioned according to income – Fourier was not opposed to class divisions – by long iron-and-glass covered walkways not dissimilar to Kahn’s later industrial buildings. It was a high-tech machine-age utopia, and like Ford’s plants the layout of the phalanstery was determined by the flow of production, but what was being made here went far beyond mere money: it was pleasure itself.

In addition to all the specialised spaces enumerated above, the phalanstery was to contain rooms dedicated to the pursuit of the ‘passions’. This points to the most original aspect of Fourier’s utopian vision, his focus on psychology. For Fourier, the perfect society does not just minister to the material wants of its individual members, but also to their sensual needs, which he enumerated, following Newton’s example, as if they were natural laws. This led him to an emphasis and a startling degree of candour on matters of sexuality. He condemned traditional marriage for being a form of sexual slavery especially onerous for women. Instead, Fourier said that everyone required what he called the ‘amorous minimum’ – the satisfaction of their sexual desires no matter how unconventional. He thus argued for the toleration of homosexuality (he was a big fan of lesbianism); for the institution of administered orgies at appointed hours in a dedicated room in the phalanstery called the Court of Love and for ‘amorous philanthropy’, in which lithe young things would minister to the needs of the elderly and disabled. Toleration is the wrong word for Fourier’s approach: he did not encourage a wishy-washy liberal response to human diversity; he revelled in difference, which he argued promises the greatest and most interminable pleasure for all. Satiation – the one great danger in his utopia – can only be kept at bay by endless variety. Fourier extended this reasoning to labour, arguing, ‘In work, as in pleasure, variety is evidently the desire of nature.’12 Since any task gets tiresome after one or two hours he proposed a constant swapping of professional roles; Fourier, despite his organisational mania, would have hated Ford’s factories.

Fourier’s followers, including his American translators, cut out his references to sexuality in order not to terrify their prudish audiences, a bowdlerisation that incensed the old man. However, thus shorn of its more hair-raising aspects, Fourierism spread like wildfire. In France one of Fourier’s most successful disciples was an iron stove manufacturer named Jean-Baptiste-André Godin, who built an enormous commune – he called it a Familistère – for his workers in Guise, near Paris. The large glazed shared spaces of these buildings and the centralised cleaning and cooking facilities closely followed Fourier’s phalanstery, and the experiment was highly successful. Founded in 1846 and later given over to cooperative ownership and management by the workers, the Familistère was only closed in 1968, when the company was taken over by Germans.

Apartments, cooperative shops, a garden, nurseries, schools, a swimming pool and a theatre made up the Familistère built by Godin for his workers in the 1850s

Fourier’s ideas had a much greater if more evanescent impact on the other side of the Atlantic, where in the 1840s there was a national craze for collective working and living, and numerous communities sprang up with startling names like Utopia, Ohio. The most famous of these was Brook Farm, set up in the countryside outside Boston by a Unitarian minister named George Ripley in 1841. To house the commune Ripley began work on a large phalanstery

one hundred and seventy-five feet long, three stories high, with attics divided into pleasant and convenient rooms for single persons. The second and third storeys were divided into fourteen houses, independent of each other, with a parlour and three sleeping rooms in each, connected by piazzas which ran the whole length of the building . . . The basement contained a large and commodious kitchen, a dining-hall capable of seating from three to four hundred persons, two public saloons, and a spacious hall or lecture room.13

Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was briefly a member of this phalanx, immortalised his experience in a roman-à-clef entitled The Blithedale Romance. Unconvinced by the project, he gently mocked the aspirations of the settlers: ‘We meant to lessen the laboring man’s great burden of toil, by performing our due share of it at the cost of our own thews and sinews. We sought our profit by mutual aid, instead of wresting it by the strong hand from an enemy, or filching it craftily from those less shrewd than ourselves (if, indeed, there were any such in New England).’14 But economic problems quickly led to the collapse of the commune – quite literally, when the yet incomplete and uninsured phalanstery building burned to the ground in 1847. However, Hawthorne identified other sources of potentially calamitous discord: in The Blithedale Romance communal life disintegrates when a tangled network of desire develops between the narrator, his puritanical friend Hollingsworth and two young ladies. Hawthorne was familiar with Fourier’s work, and in one scene in The Blithedale Romance his narrator mischievously brings the suppressed erotic element to the surface.

I further proceeded to explain, as well as I modestly could, several points of Fourier’s system, illustrating them with here and there a page or two, and asking Hollingsworth’s opinion as to the expediency of introducing these beautiful peculiarities into our own practice. ‘Let me hear no more of it!’ cried he, in utter disgust . . . ‘Nevertheless,’ remarked I, ‘in consideration of the promised delights of his system, – so very proper, as they certainly are, to be appreciated by Fourier’s countrymen, – I cannot but wonder that universal France did not adopt his theory at a moment’s warning . . .’ ‘Take the book out of my sight,’ said Hollingsworth with great virulence of expression, ‘or, I tell you fairly, I shall fling it in the fire!’15

Hawthorne implies that the suppression of Eros by reformers like the mini-Robespierre Hollingsworth can lead only to social discord, and one might speculate that if Eros had not been suppressed in the American phalansteries, these communities might have had a bit more to offer their increasingly disillusioned inhabitants than hard work and bad food. There was a lesson for Ford too in Blithedale and in Fourier as a whole: by refusing to satisfy the sensual needs of consumers and workers, Ford’s enterprise was doomed to failure.

Ford’s attempt to create a harmonious and optimally profitable industrial universe turned sour because he tried to chase pleasure out of the spheres of production and consumption. Ford’s Sociological Department took a prescriptive and antiquated view of sexual morality, and in trying to impose his own hypocritical Victorian values on his workers at home, he alienated their emotional lives from work at the very same time as attempting to reconcile the two. Then, sensing his failure, he turned from administrative compulsion (via the sociological survey and the five-dollar day) to the brute force of his Service Department, and was doomed. Meanwhile, Ford’s rival Alfred Sloan at General Motors had spotted a chink in the armour of the world’s greatest manufacturer. There was no way GM could out-rationalise Ford, so instead they decided to offer consumers a wider range of more attractively designed products, putting sensual pleasure back into the sphere of consumption although not addressing the parallel problem of the denial of pleasure in labour. Nonetheless by the mid-1920s GM was outselling Ford for the first time, and after resisting the entreaties of his executives for years, in 1927 Ford was finally convinced to discontinue the Model T in favour of the more seductively styled Model A – now available in several colours besides black. But Ford had lost his advantage, and he would never regain his position as the world’s greatest manufacturer.

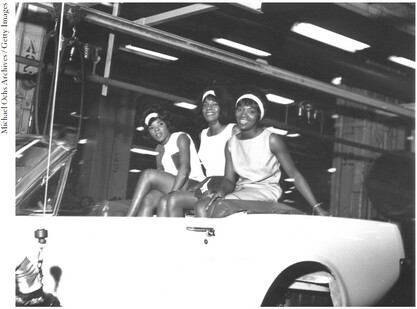

Sex in the Rouge: Martha and the Vandellas perform their 1965 hit ‘Nowhere to Run’.

Despite Ford’s own failure, Fordism itself survived – and indeed flourished – after the Second World War by mutating into something that would have deeply disturbed its founder. This change was fuelled by credit – of which Henry Ford, ever watchful for ‘Jewish’ finance, disapproved – and sex. The new Fordism erupts into seductive life in a performance of Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ hit ‘Nowhere to Run’, which was filmed on the assembly line of the Rouge in 1965. (Motown’s boss, Berry Gordy, had worked at the factory before starting his record label.) Three young and impossibly glamorous singers dance among the workers building Ford Mustangs, with the implicit equation of the women, as consumable sex objects, with the interchangeable mass-produced parts around them. The song’s producers actually used car parts – shaken snow chains – to create an insistent percussive effect running throughout the track, a precursor of the starker industrial sound that was to emerge from Detroit with techno in the late 1980s. The rattling chains refer to the tortured and inescapable relationship described in the song, but they are also the sound of the all-pervasive force of industrial capital, which has invaded the realm of Eros via pop culture: ‘nowhere to run, nowhere to hide’. Rest has become ‘leisure’ and pleasure has become work – a pretext for consumption.

An archly self-aware celebration of the same process appears in satanist and avant-garde artist Kenneth Anger’s short film Kustom Kar Kommandos. Filmed the same year as the Vandellas’ video, this three-minute slice of pastel-hued homoerotica shows a young man lovingly buffing the paintwork of his car to the soundtrack of the Phil Spector-produced hit, ‘Dream Lover’; incredibly, the film was funded by a $10,000 grant from the Ford Foundation.

Ford would not have approved. Nevertheless, in later life – seeming to realise that he had gone wrong somewhere but still unable to acknowledge the importance of sensuality – Ford had begun to grope backwards towards American utopianism, arguing that rural life should be industrialised, and industrial life agriculturalised, as he put it. By this he meant that he wanted to decentralise industry, so that the huge factory complexes that he had created were broken up into smaller establishments spread out in bucolic settings. His aim was for workers to reunify work and life in some kind of prelapsarian industrial Eden. However, his Arcadian impulse could never have competed with the more potent attempts of late Fordism to harness the power of the domestic sphere that had developed after the war: the use of advertising and pop culture to eroticise labour and consumption in the home. The crucible in which this alchemical process took place was the kitchen, where, in a perverted fulfilment of Ford’s hopes, domesticity was industrialised and industry domesticated.

The middle-class American dream of the rationalised kitchen, which had begun in the 1840s with Catherine Beecher, was now marketed to a much broader section of the populace, the new middle class, with its disposable income provided by Fordist labour. Capitalists wanted to reabsorb some of this ‘surplus’ wealth back into their profits, and by portraying the work of the housewife as an effortless joy, advertising – its imagery rife with sexual innuendo – powered up the home, and labour and consumption within it, with an electrifying erotic charge, making the kitchen and its gadgets irresistible symbols of very traditional femininity. Thus domesticity was brought completely into the industrial universe, as a site of mingled consumption and labour but on a purely individualistic footing. Despite the emphasis on pleasure, there is nothing of Fourier’s phalanstery here. There is no shared reduction in the burden of domestic chores – the promise of ‘workless washdays’ turned out to be an empty one as manufacturers ramped up hygiene standards in order to keep people buying more and more specialised appliances. There are no futuristic glazed streets, stately pleasure domes or provisions for the ‘amorous minimum’, just lonely greed dressed up as happiness. Nor is there anything of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s political vision for the modern kitchen. The kitchen is painted as a place of consumption, not work, although of course work still goes on there, and its users are not freed by convenience but enslaved by it.

These two approaches towards work and the home – Fourierist and Fordist – met in their death struggle on another continent far from the steamy kitchens of American suburbia. The Soviet Union might seem an unlikely place to find Fordism, or Fourierism for that matter, as party orthodoxy saw Fourier as a faintly bonkers precursor of ‘scientific socialism’, but Ford was lionised during the Russian Revolution. His portrait was hung beside Lenin’s in factories, and the party invited Albert Kahn to build hundreds of plants between 1928 and 1932 as part of the first five-year plan. (Initially most of these produced tractors, but they were later converted to build the tanks that crushed the Nazis.) The popularity of Fordist ideas in the USSR demonstrates a peculiar similarity between capitalist and communist economies, both of which tend to disregard the importance of satisfaction in work in favour of the imperatives of hyperproduction, whether in the cause of profit or some future utopia. However, during the heady early years of the USSR – before Stalinist orthodoxy closed like a vice – there was room for more imaginative rethinkings of the way that life and work might be organised in a communist utopia. Lenin himself was deeply inspired by a Fourierist novel, What Is to Be Done? by Russian writer Nikolai Chernyshevsky, which proposed the construction of gigantic glass communes dispersed throughout the countryside.

Feminism also flourished, and revolutionaries such as Alexandra Kollontai, later Soviet ambassador to Norway, the first female ambassador in the world, argued that under communism traditional families and gender roles would wither away, childcare would be collectivised and free love would reign. Such ideas blossomed in architecture, and a group of young visionaries called the constructivists designed (but did not build – there was very little money or opportunity for building during the post-revolutionary period) structures that would usher in new communal ways of living and working. The most famous of these was Vladimir Tatlin’s 1919 Monument to the Third International, a gigantic canted tower of high-tech iron and glass, designed to hold rotating assembly rooms. The unbuilt tower points eternally to a glorious future, unlike the static, status-quo-affirming Eiffel Tower to which it is a riposte.

In later years the constructivists managed to get a surprising amount of work built, even during Stalin’s first five-year plan. Mosei Ginzburg’s famous 1930 Narkomfin building in Moscow is a touchstone of late constructivist design, a huge communal house designed to be a ‘social condenser’ – a means of reshaping society by bringing people together in new combinations. It was meant to be a prototype for all future Soviet housing, but in reality very few domestic buildings were put up during this period. Industrialisation was a much higher priority for the party, and most urban citizens continued to live in dirty overcrowded tsarist apartment blocks. The contrasting abstraction of Ginzburg’s clean white structure was inspired by European modernists like Le Corbusier – and by the machine aesthetic, which was also in vogue in Russia during the 1920s and early 1930s – but Ginzburg wanted these formal innovations to adorn a socialist utopia, not just the villas of rich industrialists. Accordingly, the Narkomfin building was to contain a public kitchen and dining room, a gym, a reading room, childcare facilities and shared clothes-washing facilities – so far, so Fourierist. The idea was that in the communist future sleeping would take place in private individual cells, and all other activities, both leisure and labour, would be shared. Even sex would be unchained by the revolution.

But the constructivists – tempering their aspirations to fit in with party orthodoxy, which had retreated from the enthusiastic idealism of the 1920s – recognised that people could not suddenly be forced into this new way of life. To ease the transition, the Narkomfin building included a variety of living spaces, gradated from traditional flats to dormitories. The 200 prospective residents were meant to come in one end as bourgeois nuclear families, and pop out the other as shiny new communists: this was the home reconceived as a production line for people, not just ‘a machine to live in’, which was Le Corbusier’s fundamentally different industrial metaphor. Social change is built into the structure – not indeterminate change, as in Ford and Kahn’s River Rouge plant, but change towards a preconceived form, communism. Despite its Fourierist touches, the Narkomfin building also shared something of Ford’s approach to domesticity: both attempted to eradicate private life, whether by paternalistic supervision in the case of Ford’s Sociology Department, or by minimising private spaces in Ginzburg’s building, in order to harmonise domesticity and labour, fusing the two in an optimally productive relationship.

This ‘utopia’ never came. Just as the Narkomfin building was completed Stalin tightened his grip on thought and expression, imposing his own deeply backward views on society. The same year he shut down the Zhenotdel, the women’s section of the party, thus ending attempts to revolutionise gender roles. Uncle Joe didn’t much like modernist architecture either: he wanted people to live in bombastic classical apartments, not futuristic laboratories for a new way of life. Foreign influences were henceforth considered deeply suspicious, and Ernst May and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, who had fled Nazi Frankfurt to help build the new Russia along with numerous other left-leaning Germans, were forced to leave the country. Many native modernists were not so fortunate, and ended up being ‘re-educated’ or worse. The Narkomfin building was one of the first canaries to fall off its perch in this airless coal mine. Shortly after its completion a party bigwig insisted on having a private penthouse constructed on the roof exactly where a communal terrace was meant to be, and its builders felt compelled to denounce their effort as a failed experiment. Future housing projects bowed to Stalin’s retrograde ideas, and utopian communalism fell out of fashion for decades.

After many years of hibernation, however, these ideas re-emerged blinking into a brave new Soviet dawn. In the wake of Stalin’s death in 1953 Nikita Khrushchev initiated a thaw in Russian intellectual life. For a while concepts that had been unmentionable in the 1930s crawled out of the woodwork, and constructivism was reassessed: it was no longer counter-revolutionary ‘formalism’ but a homegrown socialist art movement to be (cautiously) proud of. The residents’ committee of the Narkomfin building, which had fallen into neglect and its facilities adapted to other uses, petitioned for a reinstatement of the original communal areas and programmes. This was never granted, but for a while Fourierist ideas of shared cooking, cleaning and childcare were in the air. In fact, between 1957 and 1959 a variety of housing types were considered as part of a crash programme of home building, during which millions of citizens were rehoused in clean new apartments. Both communal and private kitchens were promised, as adherents of late-Fordist ideas about work and domesticity battled Fourierist-style communalists for supremacy in Soviet architecture. On the one hand it was argued that Russians needed private well-appointed homes as sites for communist consumption, and on the other that dormitories with shared facilities were more in accordance with socialist principles. Combinations of the two were also suggested, with the proposal that consumer goods be publicly owned so that they could be rented out by private householders.

Eventually the Fordists won the argument, to the lasting economic detriment of the USSR, which could not sustain American levels of consumerism. But it seemed for a while that it might: this was the tantalising era of Red Plenty, to borrow Francis Spufford’s name for the brief period when the USSR seemed to be overtaking the capitalist West. These days, with the ignominious collapse of the Soviet empire still fresh in our memories, we tend to forget that there was a moment – between the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 – when Russia seemed like it might win the Cold War. The Soviets had embraced and even surpassed Western technological achievements; they were winning the space race (Yuri Gagarin went into orbit in 1961); their economy was growing faster than any other bar Japan’s; they were producing an incredible number of engineers and scientists; and they were leading the field in cybernetics in order to create – it was desperately hoped – a microchip-planned economy. Khrushchev knew that he had to offer the Russian people, worn down by decades of war, famine and enforced ideological conformity, a concrete hope of a better future – no longer some misty communist Neverland, but a real, unambiguous fulfilment of current needs and wishes. In an abysmal misjudgement, the year 1980 was chosen as the one in which Soviet society would overtake America. In twenty years the communist cornucopia would overspill, in Spufford’s words, with ‘Ladas quieter than any Rolls-Royce. Zhigulis so creamily powerful they put Porsche to shame. Volgas whose doors clunked shut with a heavy perfection that made Mercedes engineers munch their moustaches in envy.’16

People really believed this stuff, and not without reason. Previously unheard-of material comforts were becoming available to ordinary Soviet citizens. Shops were full, and the streets were packed with people dressed in bright new clothes. But the party – which was all too aware of the inadequacies of the country’s creaking corrupt economy – knew that Khrushchev’s vision was unattainable. He was deposed in 1964, his promises officially forgotten, but they lived on in the minds of Russians, steadily eroding the legitimacy of the party. So why on earth did Khrushchev make his ludicrous promise of ‘communism in twenty years’? The blood-soaked Stalin era weighed heavily on his conscience, for a start, and it seems he genuinely wanted to make amends by delivering the happiness that communism had always held out to its adherents. But this was as much a response to international as domestic politics.

In 1959 the world’s two superpowers had locked horns on one of the most bizarre battlegrounds in history, a show kitchen at the American National Exhibition in Moscow. The famous ‘kitchen debate’ that took place there between Khrushchev and Vice-President Nixon was a pivotal moment in the Cold War, when the Fordist American dream of mass consumerism went head to head with the Soviet ideal of Red Plenty. The American show kitchen was consciously intended as propaganda by white goods – or rather pastel pink and canary-yellow goods, for in true late Fordist style the units and appliances supplied by General Electric were available in a wide variety of colours. Consumer choice, then as now, stood in for democratic representation: this was pure kitchen-sink politics.

The futuristic machines on display included a robotic floor-washer and a mobile dishwasher. Faced with all this automation, Khrushchev asked Nixon, ‘Don’t you have a machine that puts food into the mouth and pushes it down?’ His remark brims over with contempt for capitalist greed and sloth but does nothing to disguise the fact that he had been wrong-footed by the everyday opulence on display. The terms of the Cold War had been changed: the Americans, who were losing the space race at the time, had withdrawn to the home front, and Khrushchev’s insistence on victories won in space and the lab could not compensate for the more tangible defeat in the arena of the kitchen. No matter that the Russian papers pointed out (quite rightly) that few Americans could afford such high technology and that most US homes were bought on crippling mortgages; people queued in their thousands to file past these artefacts from another civilisation, each visitor being implanted with a seed of candy-coloured doubt. There was no longer any Fourierist alternative of communally shared labour on offer. Late Fordism – with its welding together of consumption and production, work and pleasure in the private home – prevailed, and those rattling chains echoed across the Iron Curtain: ‘nowhere to run, nowhere to hide’.

Fourier, with his emphasis on communal living and sensory pleasure, might seem to offer an alternative to this late Fordist consensus. But Fourier, as I’ve hinted a few times during this chapter, was not so far from Ford after all. His mania for categorisation descends from the same Enlightenment motives that lie behind Ford’s rationalising approach to work, and with his emphasis on ‘passions’ he strangely anticipated the condition of late Fordism. ‘A general perfection in industry’, he argued, ‘will be attained by the universal demands and refinement of the consumers, regarding food and clothing, furniture and amusements.’17 He continued: ‘My theory confines itself to utilising the passions now condemned, just as Nature has given them to us and without in any way changing them.’18

But, as it turned out, passions were altered by being industrialised. Fourier wanted to pin down and dissect protean human sexuality just as minutely as Ford cut up the worker’s body, and the scars left by his surgeon’s knife can be seen today in the reports of marketeers, whose investigations into the fifty-seven varieties of desire are carried out in the service of consumerism. As a result, pop culture and advertising have supplied us with new objects of desire, suffused with the glow of promised erotic pleasure. By taking on board the areas of human experience suppressed by Henry Ford and incorporating them into the realm of consumption, late Fordism successfully and profitably integrated passions into industrial society. But there is one aspect of Fourierism that has never been realised, Google workers on beanbags notwithstanding. ‘Life,’ Fourier wrote, ‘is a long torment to one who pursues occupations without attraction. Morality teaches us to love work: let it know, then, how to render work lovable, and, first of all, let it introduce luxury into . . . the workshop.’19 In our post-Fordist era, when manufacturers have stopped paying workers enough to buy their products and shipped their operations to cheaper labour markets instead, the luxurious workshop seems further away than ever. The sea hasn’t turned into lemonade yet, either.