5

The Complicated River

Nepisiguit Watershed, Summer 1899

The Nepisiguit, then, I submit, is a composite of four rivers, a small portion from the Tobique system, a very large part from the Upsalquitch system, a part from the Miramichi system, while the lower portion is the true Nepisiguit, which has worked back at its head, gradually capturing and making tributary to itself the aforementioned parts of the other systems.

— W.F. Ganong1

In the final years of the nineteenth century, Ganong carried out two extensive field trips into the heart of New Brunswick’s wilderness. The first, in 1898, started in the Nepisiguit watershed and ended in the Tobique. The following summer, he began in the Tobique watershed and concluded in the Nepisiguit. From these two field trips, he learned to launch future field trips into the province’s central highlands from the Tobique River to take advantage of the ease of travel to the upper reaches of the river and their access to the headwaters of several other important watersheds.

In 1899, after spending time at his summer home in Saint John, he travelled by train to Fredericton and then on to Newburg Junction near Woodstock. There he met his companion Mauran Furbish, a friend and fellow naturalist from Massachusetts. Throughout the trip, the two worked together to document the physiographic character of the river. Furbish’s camera provided images of the trip, and Ganong scribbled field notes and sketched maps. Their data were later used in reports and also formed the basis for subsequent field trips, since the knowledge gained on each trip became the foundation for the next.

W.F. Ganong’s map of Nictor [Nictau] Lake and the Upper Nepisiguit River (PANB-MC1799)

Eager to begin their fieldwork, the two men immediately journeyed by train farther up the Saint John River Valley to Perth-Andover, all the while noting the physiographic nature of the river. At Perth-Andover, they boarded another train for the trip to Plaster Rock where they hired horse and wagon to transport them up the Tobique River to either the settlement of Riley Brook or nearby Nictau.2 With the tote road going only part way, they loaded their belongings onto a barge that was towed upriver by a team of oxen. It took two days to complete the forty-eight kilometre stretch, giving Ganong ample time to become acquainted with the Tobique Valley’s physiography.

The settlements at Riley Brook and Nictau each had a hotel, frequented primarily by American sports during hunting and fishing trips.3 Ganong often chose one of these communities as a starting point for his field trips, and occasionally as a place to rest before or after a particularly tiring journey. On this trip, the two explorers stayed only long enough to acquire a canoe, rations for the field trip, and the aid of a guide for the two-day trip up the Little Tobique River to Nictau (Nictor) Lake at the base of Mount Sagamook.

Ganong examined the lake and mountains thoroughly in order to understand the geology and record the physical geography of the area in detail. He surmised that Nictau Lake was formed by debris left behind after the last glaciers receded, also turning the waters of Lake Nepisiguit away from the Tobique River and towards the east and the Nepisiguit River. It was a theory that became the basis for much of his work on the formation of the province’s river systems, a topic that he returned to over and over again.

In the whole of the attractive science of physiography, there is no subject of greater importance or interest than the changes, which river valleys undergo in the course of their evolution. Rivers are forever extending their basins and moving their watersheds, while frequently they capture other rivers. Hence it comes about that some rivers are composites of two or more streams originally separate.4

The Nepisiguit River’s constant changes in direction intrigued Ganong, who noted:

Twice in its course it bends permanently at right angles; it has a remarkably irregular drainage basin, and a valley which, through most of its extent, lessens in breadth and increases in slope towards its mouth. Such a river must have a complicated history, and it is, I believe a composite of four different river-systems.5

Big Nictau Lake from Mount Sagamook, September 2014 and summer 1899 (Bottom: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-228)

W.F. Ganong’s map of Nictor (Nictau) Lake, 1899 (PANB-MC1799)

While at the lakes, Ganong and Furbish spent several days measuring the depth and the temperature of the water. The beauty and isolation of the lake impressed them deeply, and Ganong’s report emphasizes its wilderness appeal:

At the eastern head of the Tobique River, in the north of the New Brunswick Highlands, lies Nictor, fairest of New Brunswick lakes. It is absolutely wild, unvisited save by an occasional sportsman or naturalist, and may be reached only by several-days canoe journey. It is un-surveyed, wrongly mapped, and scientifically little known.6

As Ganong gathered data to map the lake correctly for the first time, he had for reference only the rudimentary historical maps then available. He noted of his equipment: “I used a fair prismatic compass, and a simple home-made apparatus on the stade principle for measuring distances; the general shape must be nearly accurate, though its proportions may be somewhat in error.”7 Despite any misgivings, he was later able to make detailed maps of the lake and river, ensuring that all essential features were noted. With Furbish’s photographs, they provided the first accurate documentation of the lake and region.

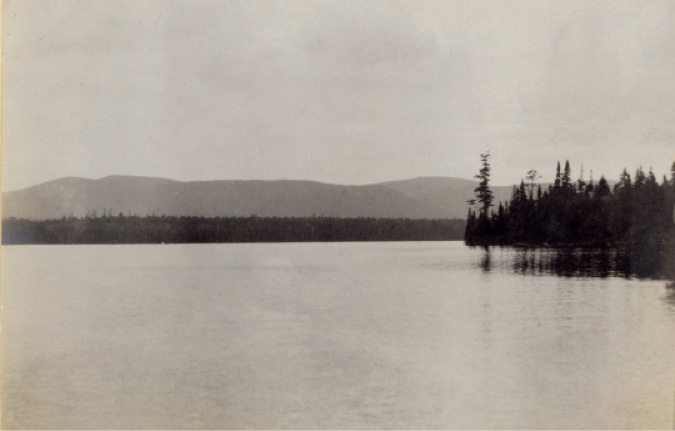

Looking northwest across the Nepisiguit Lakes toward Governor’s Plateau, June 2012 and 1899 (Bottom: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-45)

Ganong and Furbish next ascended the difficult eastern face of Mount Sagamook. They determined that it was not a solitary peak but the northern point of a mountain chain that Ganong called the Governor’s Plateau. A shallow valley separated Mount Sagamook from Mount Head and, farther to the south, Mount Carleton. Ganong wanted to determine if Sagamook was truly the highest peak in the province, rather than Big Bald Mountain at the headwaters of the South Branch Nepisiguit River. Although his measurements showed it was not, Sagamook won Ganong’s heartfelt praise:

Above all and over all, however, towers grand Sagamook. Rising steeply over sixteen hundred feet directly from the lake, higher than any other New Brunswick hill rises from the water, clothed with living forest except for a few bold bosses near its summit, shrouded often in mists, it is easily the finest, even though not the highest, of New Brunswick hills.8

Ganong still suspected that Big Bald might not be New Brunswick’s highest peak, so he devised a plan to check it against Mount Carleton through “a comparison of careful theodolite measurements made from the summit of each.”9 With his characteristic determination, Ganong revisited the region in 1903 and conducted aneroid barometric measurements for greater accuracy, determining that the mountain he named Mount Carleton was actually the highest in the province.

Exploration of the mountains and lake finished, Ganong and Furbish left the region by portaging from Nictau Lake over the height of land to Bathurst Lake and the Nepisiguit Lakes at the head of the Nepisiguit River. They followed a route that had been a traditional Mi’kmaq portage between the watersheds. Before canoeing down the river, the two men explored the lakes. In a small inlet near Mount Teneriffe, they took temperature and depth readings from a shallow area where the bottom lay only inches from the surface. Ganong also sampled the content and consistency of the mud and concluded that, like many of the mud lakes in the province, the inlet had been formed by the continuous deposit of decayed organic material that he later determined to be alive with algae and diatomic plants.

Below the lake system, the river twisted and turned through a magnificent chain of mountains to its confluence with Silver Brook. The scientists stopped frequently to take side trips to the tops of mountains and up the river’s major tributaries. They measured distances and elevations, determined physiographical features, and gathered information for future fieldwork. These side trips also fulfilled the secondary role of determining the likely paths of the many Native portage routes.

From previous field trips, Ganong expected to find a portage between the Nepisiguit watershed and the Upsalquitch River, but he was unsure of its exact location. Just below Silver Brook, the river straightened and opened into a wide valley. They set up camp at the mouth of the promisingly named Portage Brook. Ganong suspected that the valley might once have been a river that flowed north into the Upsalquitch, making it a logical portage route. He was close but not close enough. “After much debate as to whether to go by canoe or risk the portage now,” he recorded in his field notes, “— decided for latter — and travelled 8 miles up Portage without of course reaching the lake and returned disgusted.”10 When Ganong returned in 1903, he discovered just how close he had been, noting: “there is a low and easy portage to Upsalquitch Lake, which lies 100 feet lower than the mouth of Portage Brook.”11

Ganong and Furbish continued paddling downriver, stopping at the confluence of the Nepisiguit with the South Branch to reconnoitre before Indian Falls, a series of rapids that stretched almost a kilometre. They camped at the lower end of the falls, adjacent to a deep pool where trout and salmon were plentiful. An enthusiastic Furbish wrote in his diary: “Ran to Indian Falls and portaged before dinner — enjoyed delightful afternoon fishing, loafing — the finest day of the trip.”12

The paddling to this point was smooth and brisk, but Ganong found the river beyond the falls to be geologically different, reporting:

This part of the river, from Indian Falls to Nepisiguit Brook, is very puzzling, and I have not been able to form any clear idea of its probable mode of formation.…Certainly all this part of the main Nepisiguit must be comparatively new, much newer than the upper section of the river.13

Mount Teneriffe from the Nepisiguit Lakes, June 2012 and 1899 (Bottom: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-3)

The Upper Nepisiguit River, June 2012 and 1899 (Bottom: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-2)

Beginning at Nepisiguit Brook, ledges and the narrowing river created many cataracts, meaning tricky paddling and more portages. Ganong hypothesized that the section between the falls and the narrows was a part of the Northwest Miramichi River that glacial action had rerouted. Along the north bank of the river just above the narrows, he spent a day inspecting large flat stones that appeared to have been fitted together. He attributed the phenomenon to large amounts of glacial meltwater that coursed through the narrows and forced boulders into the softer soil, smoothing their upwards-facing portions to create a surface resembling a cobblestone road.

Below the narrows was a magnificent Nepisiguit Falls,14 and a sheer walled gorge rose high above the narrow channel. It ended in what British and American sports considered one of the finest salmon pools in the province. Although the river valley gradually widened after the pool, some narrow channels with challenging rapids and cascades occurred, notably at Middle Landing.15 The river finally became easier paddling below Pabineau Falls, Boucher Falls, and the stretch known as Rough Water. Ganong and Furbish soon approached the Bay of Chaleur and the town of Bathurst and the end of their expedition.

Through this field trip, Ganong became concerned that the cutting of trees along the Nepisiguit, Tobique, and Miramichi watersheds threatened to forever scar the Nictau Lake wilderness. In an 1899 presentation titled “The Forestry Problem In New Brunswick,” he called the unmanaged forest the province’s greatest natural wealth and warned that it was deteriorating steadily. He felt that the general public of the time was uninformed and thus indifferent and that the government was not taking an active role in proper resource management. He condemned short-sighted forestry practices, writing:

No pulp mill should be allowed to operate in New Brunswick in a way to deforest any piece of land, for a speedy profit of this kind will be dearly paid for in the future. The only wise method in forestry management is to keep a forest intact, and this can be done only by a system of rotation in cutting, by which the larger trees alone are removed, the smaller being left to grow.16

The gorge below the Nepisiguit Falls, May 2008

Ganong’s work to understand the Nepisiguit River formation was also instrumental in developing his system of classification for New Brunswick rivers. In the spring of 1899, he presented a paper, “On a Division of New Brunswick Into Physiographic Districts,” to the Natural History Society. The divisions, based on river systems and geological irregularities, helped to explain the province’s historic travel routes and the distribution of settlement and brought together human and natural history. Through Ganong’s research, other members of the society also began to understand the importance of the region, especially the headwaters of the Nepisiguit and Tobique watersheds.

In the conclusion of another paper, “On The Physiography of the Nictor Lake Region,”17 Ganong urged the citizens of New Brunswick to protect this valuable wilderness for future generations. “Nictor Lake, therefore, lies to-day not only by nature that most charming place in the interior of New Brunswick, but as yet entirely unspoiled,” he argued, going on to ask: “But why should not the people of New Brunswick prevent its despoiling, and set aside the lake and its shores as a provincial park, to be kept wild and beautiful for their enjoyment forever.”18