7

The Primeval Wilderness

The Little Southwest Miramichi River, Summer 1901

I crossed New Brunswick from the Tobique River to the mouth of the Miramichi, by way of Trowsers, Long, Milnagek (Island), Little Southwest (Tuadook) Lakes and the Little Southwest Miramichi River.

— W.F. Ganong1

Never wanting to leave fieldwork incomplete, Ganong returned to the Negoot Lakes in the summer of 1901 to undertake an ambitious field trip and to conclude unfinished research. His focus that summer was the relationship between the Negoot branch of the Tobique watershed and the Little Southwest Miramichi watershed. Ganong’s need to collect accurate data led him to undertake an extended elevation study from the Tobique to the Little Southwest Miramichi. To ensure accuracy, he used three different instruments, which he personally calibrated. Prior to the trip he took baseline measurements at Fredericton and Chatham to provide an accurate comparison for all future elevation measurements, writing in his report: “The instruments and methods used, and the care exercised in all observations and calculations are such as to make me feel confident.”2

After spending time in Riley Brook to rest and gather supplies, he and Mauran Furbish retraced their trip of the previous summer along the portage road to the Negoot Lakes. Gaining confidence with their wilderness skills, they went without a guide on this trip, preferring to go it alone. This was not out of character for Ganong, who often preferred solitude during his trips. At Trowsers Lake they spent a few days re-measuring elevations and checking for consistent results. On August 3, 1901, while camping on the shore, they witnessed the uncommon sight of a lunar rainbow over the lake.

About ten o’clock, a light shower with fleecy clouds came up opposite to the waning but bright moon, and against the clouds appeared a very perfect bow with the arch complete. No colors were visible, but instead the bow was a grayish light, not unlike the northern streamers.3

Ganong and Furbish departed Trowsers Lake, pushing farther inland by way of an old portage trail to gain access to Long Lake. Retracing the route used in 1900, they paddled down its length, all the while taking elevation measurements, to the mouth of a small brook emptying from Milnagek Lake. A high ridge forming the southern end of Long Lake meant they had to carry their equipment and line their canoe up the turbulent brook as they explored for the shortest path from the Right Hand Branch Tobique watershed, to the Little Southwest Miramichi. From Milnagek, the companions made their way to Squaw Lake and the surrounding Squaw Barren in the Central Highlands before returning to spend several more days recording data on the lake and the surrounding hills that form the divide between the watersheds. He noted of Squaw Barren:

On the west it drains into Squaw Lake, an affluent of Tobique, and on the southwest into Rumsey Lake, a beaver pond draining into the Little Southwest Miramichi. It cannot often be that a bog forms the watershed between two systems so important.4

Ganong considered the high lake and its feeder ponds to be among the most scenic areas in the province:

The scenery of Milnagek is beautiful. On the east, south and west the hills rise 200 to 300 feet near the lake, and are densely wooded with a fine, mixed forest, above which towers often the stately pine. The lake is studded with islands, all heavily forested, and between them and into the coves are many most charming vistas.5

The outlet of Pocket Lake, July 2011; 1901 (Right: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-148)

The Little Southwest Miramichi rises in the ancient central highlands of New Brunswick. From these ridges, several small tributaries drop quickly into a wide, heavily wooded basin, where they meander through barrens and wetlands, forming lakes and long deadwaters. Ganong and Furbish eventually made their way down from the highlands and through the Crooked Deadwater, around Braithwaite Mountain to Pocket Lake. The outlet of this small lake was a rock-strewn brook, like many in the region, of boulder and bog, which made it challenging to reach Tuadook Lake in the Miramichi watershed.

Ganong considered Tuadook, the largest of the Southwest Miramichi Lakes and speckled with islands, most picturesque. The pair of explorers spent several days at Henry Braithwaite’s camp on the lake, noting the physiographical attributes of the lakes — the low plateau and the ridges — as well as the richness and diversity of the surrounding forest. Braithwaite was one of New Brunswick’s foremost guides and woodsmen of the 1800s and owned hunting camps from the Southwest Miramichi River across to Upsalquitch Lake.6 Ganong greatly admired his knowledge of the area.

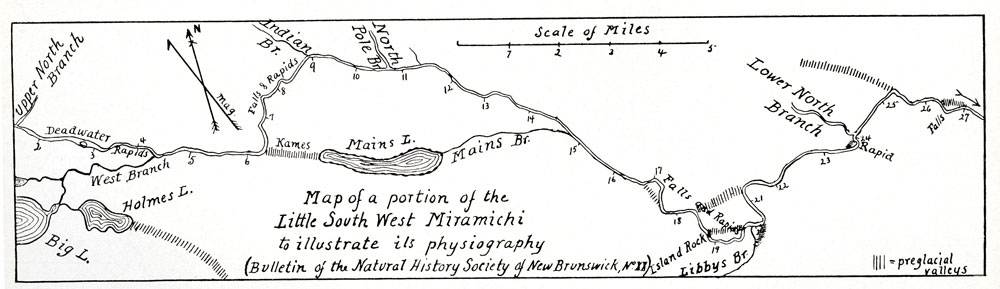

W.F. Ganong’s 1901 map of a portion of the Little South West Miramichi (PANB-MC1799)

This entire region is notable as the hunting and trapping ground of that prince of hunters, Mr. Henry Braithwaite, who knows it intimately, and who takes to it a number of sportsmen each autumn. It is a pity that Mr. Braithwaite’s knowledge of its topography and natural history cannot, through publication, be made available to others and safe from loss.7

Leaving the camp at Tuadook Lake, Furbish and Ganong were forced to pull their canoe and supplies down the boulder-strewn Tuadook River to join the Little Southwest Miramichi at Smith Forks. From the forks the river was navigable, but this changed abruptly where it turned to the northeast.

Beyond the six-and-one-half mile turn (measured from the forks with the West Branch Little Southwest), the river knifed through high ridges, forming falls and rapids and forcing Ganong and Furbish to land and portage through this rugged section along a pathway used by lumbermen and conceivably First Nations people. Ganong noted the river’s increasing roughness:

At the six and one half mile turn the river bends abruptly northward.…Less than a mile below this turn, at an elevation of 1045 feet or less, begin the bad rapids and falls which have made this river famous. Here the river narrows and falls over granite ledges and through small gorges with vertical granite walls.8

Ganong found the change puzzling until he determined that the origin was a series of kames or low sand hills that were deposited by a retreating glacier. He tracked the ancient riverbed over a series of these hills to Mains Lake and followed Mains Brook as it led back to the Little Southwest. Ganong concluded that the glacier had redirected the river, later reporting:

The interpretation of these facts might be difficult enough were it not for another brought out by the maps, namely, that in a line between the six and one-half mile bend and the mouth of Mains Brook lies the valley occupied by Mains Lake and Brook. All these facts taken together seem to point to but one conclusion, namely that in preglacial times the main river flowed through the present valley of Mains Lake and Brook. The kame hills at the six and one half mile bend constitute the great glacial dam which turned the river aside and sent it over a low part of its valley.9

The river’s difficult temperament persisted to Indian Brook and North Pole Stream, where Ganong noted that the river was less tumultuous and remained so until what he identified as the “17-mile turn,” where the original riverbed had again been dammed with glacial debris and the relatively new channel cut through a narrow, V-shaped valley with ridges high above.

From here to the mouth of Libbies Brook is the wildest section of the river. Ganong noted that the river dropped ten metres (thirty-two feet) per mile from the fork with the West Branch, where they entered the main river, to Libbies Brook, a distance of twenty-four kilometres, or fifteen miles.

At Libbies Brook they hiked a short distance to see a postglacial waterfall and an exposed ancient peneplain, characteristic of the surrounding valley. From the brook to the confluence of the Lower North Branch, the Little Southwest Miramichi River continued to drop steadily, with only a few rapids. Ganong noted that the character of the river and surrounding valley changed again below Catamaran Brook where the topology began to slope gently away from the river, producing terraces of fine sand and, further on, a broad valley. In this lower section, the river meandered around low islands before meeting the Northwest Miramichi at Red Bank. The field trip finished downriver in Newcastle, and Ganong returned to Saint John, then travelled to Massachusetts for another winter of writing and planning for the following summer.

Gary Tozer accompanied me on my trip to photograph Flaherty’s Pitch. We hiked down to Libbies Falls and then upriver along the Little Southwest to Flaherty’s on a footpath located on a ridge above the river. It is a most spectacular section of the river. We then backtracked and drove out and parked on a logging road near an area called Loggies Lodge for a short hike through the woods to Indian Falls.

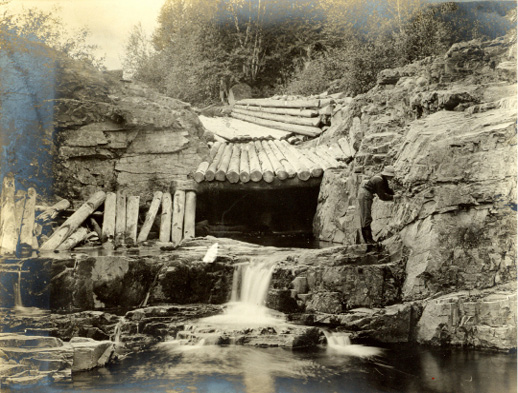

Libbies Falls on the Little Southwest Miramichi River, May 2009 and 1901. Note the rolling dam commonly used to allow timber logs to shoot over waterfalls and Ganong examining the exposed peneplain. (Bottom: NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-166)

Later that summer we drove out to Tuadook Lake. This required a drive on a very rock-strewn road and then a hike to the lake around large boulders. While at the lake we hiked to the stream that connects Pocket Lake with Tuadook.

In early October of the same year, I decided to make a solo trip out to the Crooked Deadwater. I prepared for an overnight stay to catch the waning light of day. Fortunately I chose an unseasonably warm night to camp in the woods. The drive out from the Renous highway was a bit tenuous, as my GPS and maps did not agree on the route I chose from my reconnaissance of Google Earth. Eventually, the GPS began to chirp, indicating my desired destination. The effort was well worth the image I shot that afternoon.