8

Uncharted Country

Central Highlands and Upsalquitch River, Summer 1902

The region is but rarely visited, is for the most part not yet opened up by guides for sporting purposes, and needless to say, has not yet been visited by any geologist or other naturalist.

— W.F. Ganong1

In the summer of 1902, Ganong once again returned to the headwaters of the Tobique with Mauran Furbish. This time, their plan was to spend two weeks mapping an area he called Adder Lake Stream Basin. This section of the Tobique River — and the province, for that matter — was unfamiliar and uncharted, which was more than enough to bring Ganong back to the Tobique watershed. He was most interested in a section of the highlands region called Upper Grahams Plain.

He and Furbish hiked through an open area dotted with boulders and clusters of stunted shrubs, noting:

The most striking part of the region is the Upper Graham Plains, a remarkable open elevated barren, covered with boulders, among which are some low scrubby heath bushes, lichens and the occasional whitened trunks of former small trees.2

Turning over some lichen, he found the charred remains of trees. Past forest fires had ravaged the barren, exposing numerous boulders and rocky soil. He decided that “this plain is misnamed for it is by no means a plain, but an irregular country with a general slope to the northward; indeed it is chiefly the gentle northern slope of a mountain some 1900 feet in height.”3

W.F. Ganong’s map of Adder Lake Stream (PANB-MC1799)

Ganong found numerous game trails through the basin, and he strongly suggested that it be set aside as a game refuge and breeding ground for the larger animals, such as caribou and moose. From the elevated plain he could see in all directions, providing an opportunity to map the entire region and to determine its physiographic characteristics.

Ganong wanted to explore Patchell Brook, located in the transition between Upper and Lower Graham Plains. The formation of this brook and its ravine intrigued him. An absence of forest made a tiny rivulet clearly visible “amidst great angular blocks of felsite at the bottom of an immense V-shaped gorge with solid felsite walls some 300 to 400 feet in height.”4 Later, he commented that the scene was more like one in the Rocky Mountains than in New Brunswick. Ganong wondered how such a small brook could carve such a deep ravine into the granite hillside. After much consideration he speculated that the ravine was a fault line running in a southeast direction. Meltwater from the receding glacier together with water from the Serpentine River and Adder Lake that had been blocked by glacial debris had channelled into the fault. This enormous amount of water, rock, and rubble carved the gorge and deposited the boulders at the base of the ridge. Ganong outlined the process in his November 1902 address to the Natural History Society:

These combined influences would tend to send a great quantity of water loaded with glacial debris, out through Patchell Brook, and this I believe, cut out the gorge in the comparatively short period during the melting of the glacial ice in this vicinity. The debris carried down the gorge was then spread out where it issued on the lower plain, forming the Lower Graham Plain, which is thus a rude delta of that stream.5

With their exploration of the plains finished, Ganong and Furbish returned to Nictau for a short rest and to hire a canoe and purchase additional supplies. Ganong wanted to complete research that he’d begun in 1899 in the headwaters of the Upsalquitch River. The two men began by poling the canoe up the Little Tobique River to Lake Nictor (Nictau). Next they carried their gear over the short portage to Lake Nepisiguit and canoed down the Nepisiguit River to Portage Brook. Poling up the brook, they located the long-established portage route between the Nepisiguit and Restigouche Rivers at the mouth of Meadow Brook. At Meadow Brook they canoed up looking for a location that best suited a starting point of the overland portion of the portage. Then they hauled their canoe, scientific gear, and supplies on an exhausting portage over the height of land to Upsalquitch Lake and into the Restigouche watershed.

Ganong’s 1904 report to the Natural History Society makes it apparent that he was taken by the pristine nature of Upsalquitch Lake and the surrounding mountains. He and Furbish stayed for several days, mapping the lake, sketching and measuring the height of mountains, and piecing together an idea of the preglacial physiography. Ganong speculated that the valley had tilted slightly postglacially, forcing Meadow Brook to turn away from its original course and flow into Portage Brook and the Nepisiguit. He noted: “I am inclined to think these upper Nepisiguit waters must have flowed into the Upsalquitch up to the glacial period, and that it was some form of glacial action which produced the change.”6

Ganong wrote that no fewer than ten noteworthy mountains, unnamed prior to his visit, surrounded Upsalquitch Lake. He named the entire mountain range the Naturalist Group, and gave each peak the name of a prominent person or scientist who, in his opinion, furthered the understanding of natural history. Furbish named the highest and most prominent peak Mount Ganong, in honour of his fellow explorer. The two men climbed to the summit of each mountain to survey and document the salient features of the watershed.

W.F. Ganong’s 1904 map of the Upsalquitch River and related waters (PANB-MC1799)

Looking towards the outlet of Upsalquitch Lake and the Naturalist Mountains, July 1902 (NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection Image 1987-17-1218-11)

As with other wilderness locations that he had documented, Ganong felt that the basin between the Upsalquitch and Nepisiguit watersheds should be set aside as a nature preserve for further study. He was particularly concerned about this watershed’s First Nations’ portage route because it was still intact, not yet altered by logging or roads. He noted, though, that lumbering was threatening even this remote, pristine area:

It is a coincidence more curious than gratifying that the lumbermen have reached Nictor, Nepisiguit and Upsalquitch Lakes almost simultaneously. Lumbering on the two former was just commenced last winter (1901-1902) and is to be prosecuted actively the present winter (1902-1903), as it is to be on Upsalquitch Lake.7

Ganong and Furbish next pushed north through the meadows of the Southeast Upsalquitch River. Ganong knew that sportsmen had previously followed this branch of the river, but there was scant written information. Ganong had found a published journal recording Captain Richard Lewes Dashwood’s hunting trip to the area in 1863, entitled Chiploquorgan. Maps of the lake and the upper reaches of the river lacked essential details, though Ganong’s map borrowed much from the crude sketches of the mouth of the river that the cartographer Joseph Frederick DesBarres drew in 1780.8 Ganong also relied on the county line survey map of 1872.

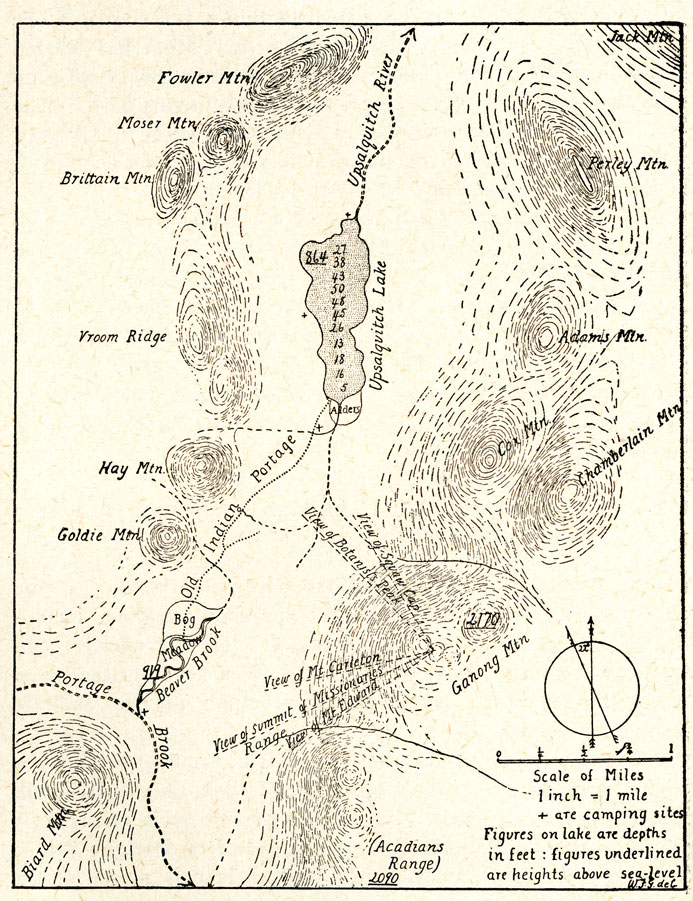

W.F. Ganong’s 1902 map of Upsalquitch Lake (PANB-MC1799)

After pushing and pulling their canoe through sluggish water shrouded in heavy brush, they reached the confluence with Eighteen-Mile Brook. Here the Upsalquitch became rougher as it flowed over a series of ledges before the beginning of the Southeast Gorge. There, the river changed dramatically again as “eight miles from the lake, it plunges into a typical, post glacial gorge two miles in length, in which the water, by a series of falls and rocky rapids, drops some 150 feet.”9 Ganong remarked on the breathtaking ruggedness of the gorge, with sheer cliffs and lush forest creating a beautiful natural setting.

The men portaged around the gorge and camped on a flat strip of land used by aboriginal peoples for centuries. Not one to ignore an opportunity, Ganong searched the portage and campsite for artifacts and ascended the gorge to examine its geological characteristics. Further down the Southeast Branch he climbed Caribou Mountain and found that it was one in a series of mountains running east and west. He took elevation measurements, made notes on the geology and studied the physiography of the lower watershed. Familiar with the geological maps of the time, he recommended an adjustment based on his findings. Below the falls, the river emerged into a broad valley and met the calmer waters of the Northwest Branch at the Upsalquitch Forks:

Below the Forks the Upsalquitch is a large and very charming river, of grand scenery, swift and abundant clear water affording ideal canoeing, extensive intervales, and all the beauties characteristic of the best of our New Brunswick Rivers. 10

Ganong and Furbish finished the summer field trip at Atholville before beginning the long train journey back to Saint John. For Mauran Furbish, this gruelling summer of 1902 was his last field trip into the New Brunswick wilderness with Ganong.

Passing storm on Mount Ganong, June 2011

On a hot, humid August morning in 2011, Gary Tozer and I drove into a large clear-cut in Lower Grahams Plain with plans to photograph the Patchell Brook ravine that Ganong had compared to the Rockies. Looking at the mountains that surrounded our route, I began to appreciate the scope of the hike. After a morning scrambling through heavy brush and deadfalls amidst blackflies and smothering heat, I finally collapsed on a rock where my GPS indicated the brook should have been. I could hear the gurgle of water, but the trees, brush, and huge scattered boulders completely hid it from view. Our hike continued up to the ridge forming the southwest edge of the ravine, but after struggling for forty-five minutes to hike half a kilometre, we resigned ourselves to returning another time.

The following May, Rod O’Connell, Karl Branch, and I found a more direct route to the ravine. We started from a clear-cut located in the transition zone where the upper plain slopes to the southeast, dropping more than one hundred and fifty metres to Lower Graham Plain. Like the lower section, it is now scribed with logging roads and has undergone intensive harvesting. We made it to the ravine and revelled in this unique geological phenomenon. I suspect little has changed in the ravine itself, except for the clear-cuts that surround it. As I photographed the ravine, I thought about Ganong painstakingly mapping the gorge and pondering the reasons for its formation.