Laying the Groundwork

William F. Ganong

In reviewing Dr. Ganong’s life-work, it is very evident that the influences which were brought to bear on him in boyhood determined the trend of his future activities.1

For more than fifty years, William Francis Ganong spent most of his summers exploring the New Brunswick wilderness. He relished his adventures in the backwoods, hiking and paddling into often-unmapped areas in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. As professor of botany at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, his job afforded him the time and financial means to follow his passion. It was during childhood, however, that he developed the love of nature and devotion to New Brunswick that led to his life’s work.

Ganong was born on February 19, 1864, in what was then Carleton, NB, and is now West Saint John. When he was seven, his parents, James Harvey and Susan E. Brittain Ganong, moved with William and his six younger siblings to St. Stephen. There, James and his brother Gilbert established the Ganong Brothers candy factory. William was inspired by his family’s interest in science and nature, especially during summer vacations at the family homestead in Springfield. He spent hours on excursions into the woods and along the shores of Belleisle Bay at the side of his grandfather, Francis D. Ganong. According to his sister, Susan B. Ganong, “he was an impressionable youth, eager to listen and learn.” She attributed all her brothers’ scientific curiosity to these family outings.

William Francis Ganong at sixteen years of age (PANB, Anne Ganong Seidler fonds P606-4)

Their grandfather, Francis D. Ganong, was devoted to the young boys and spent many hours with them, teaching them to swim, fish, handle a sailboat, drive horses and observe all forms of plant and animal life in that region. These vacations had no doubt a profound influence on the boys in creating the love of the out-of-doors and an interest in all living things. Their father James H. Ganong, was also a lover of the open spaces, and his scientific and philosophic turn of mind had its effect as well, as they accompanied him in many excursions to the woods.2

William had ample opportunity to observe all manner of flora and fauna and to develop the scientific interests that would inspire his later field trips. One of his earliest excursions without his father was a fishing trip with his uncles to Clinch Stream in the Musquash watershed in late June 1880.3 Eager to join his uncles, he borrowed his grandfather’s rather large boots, and by the time they reached camp, William was suffering from painful blisters. Even at the age of sixteen he treated the trip as a learning experience, and in this case, the lesson was less about science and more about life. His trip notes explain why he decided not to tell his parents all the details:

Did we gain or lose by our excursion? Were it not for one thing I would say most emphatically, we gained. That one thing is — we broke the Sabbath. For this reason I can never tell my folks about it without making them think how wicked I am. But that was no worse than lots of other things I have done on Sunday.4

New Brunswick Museum founder Dr. J.C. Webster described his friend’s education as follows:

The boy started life in circumstances similar to those experienced by the majority of New Brunswick boys, without special privileges or advantages of any kind, attending the public schools, as most have done, but unlike the experience of the majority of our youth he studied in a school, not registered in the Provincial Department of Education, viz, the great school of Nature.5

After distinguishing himself academically in high school, William attended the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1884 and a master’s degree in 1886. Throughout this time, he took part in summer field trips led by members of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, whom he considered mentors. A voracious curiosity and an ability to listen intently endeared him to his elders and colleagues, prompting them to share their knowledge freely. Even as a student, his prolific output of articles for the society’s bulletins distinguished him. His subjects went beyond natural history to the annals of First Nations and early Acadian settlers, and he studied the Maliseet and Mi’kmaq languages, as well as French and German.

After UNB, Ganong attended Harvard University, where he earned an applied baccalaureate degree in 1887 and became an assistant instructor in 1889. In 1888, he married Jean Carman,6 a Fredericton girl, the sister of poet Bliss Carman and the cousin of author Sir Charles G.D. Roberts, whom Ganong later reviled for personifying nature. Ganong’s thirst for knowledge next took him to the University of Munich, where he received a PhD in 1894, followed by the move to Smith College to teach botany. He was later appointed director of the college’s botanical gardens, a position he held until his retirement in 1932.

Ganong’s New Brunswick field trips took place almost every summer from 1882 until 1929, continuing throughout his years in the United States. As his age increased and his health declined, the trips became shorter. Yet, with the aid of an automobile, he was still able to visit several locations in a single summer with seemingly undiminished enthusiasm. In the summer of 1915, for example, he travelled upriver from Fredericton to the Shogomoc and Pokiok streams to determine if the physiographic nature of either would support his premise about the preglacial course of the Saint John River. From there, he travelled overland to the headwaters of the Magaguadavic and Digdeguash Rivers to complete field studies begun several years earlier. He then went north for a hasty exploration of the Tetagouche and Jacquet Rivers. That same summer, he also travelled up the Nepisiguit River to its confluence with Gordon Brook and the start of the ancient Nepisiguit–Miramichi portage trail via Portage River. This route is as historically important to New Brunswick as the Cains-Gaspereau portage described in Field Trip 15 of this book.

Ganong’s car on the Shepody Road, Kings County, 1920 (NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1225-37)

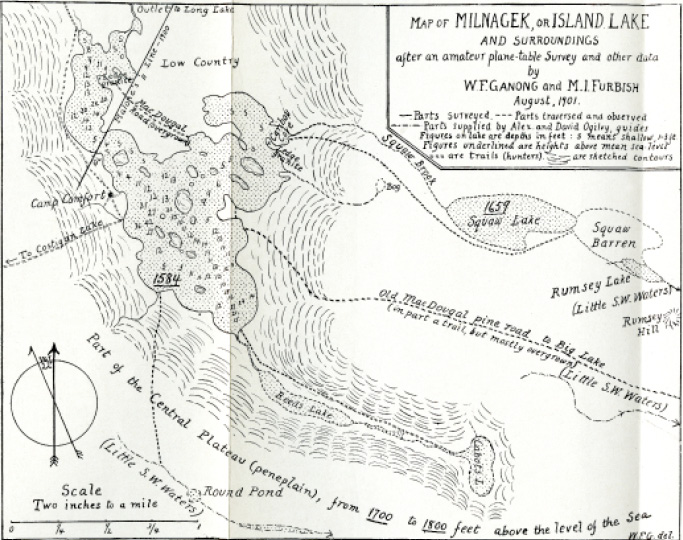

W.F. Ganong’s 1901 map of Milnagek or Island Lake and surroundings (PANB-MC1799)

Ganong always treated his field trips as serious scientific excursions, undertaken with little regard for either financial rewards or honours. His Natural History Society articles between 1884 and 1917 reflect an incredibly broad range of interests from cartography and botany to physical geography and even an English translation of Voyages to Acadia and New England from the original French of Samuel de Champlain. It is generally accepted that Ganong began the serious geographic study of New Brunswick and the Maritime provinces. Later in life, he started to write a definitive geography of New Brunswick, but he destroyed it when he realized that failing health would prevent its completion.

W.F. Ganong mapping Holmes Lake, Northumberland County, 1901 (NBM, William Francis Ganong Collection, Image 1987-17-1218-145)

Clear-cut on the Southwest Miramichi River, York County, May 2008

At the time of Ganong’s field trips, large tracts of New Brunswick had not yet been surveyed or scientifically studied, and his monographs provided the first glimpse of the province’s interior. He was exploring before the onset of road construction that opened the wilderness areas to industry and recreation. The province’s vast network of ponds, lakes, and rivers provided the primary transportation routes. Woodsmen and professional guides had established hunting and trapping lines, and geologists such as Professor Loring W. Bailey had undertaken survey work on behalf of the federal and provincial governments. Yet few others ventured into the wilderness regions, and many mountains and lakes were not even officially named. This was largely due to the extreme difficulty of accessing the areas, but as the New Brunswick Museum’s curator of botany, Stephen Clayden, noted: “His physical energy was no less prodigious than his intellectual drive.”7

In 1898, Ganong wrote about the lack of a unified topographical map system, suggesting that it would be an investment that would pay back dividends in the development of the province. Meanwhile, he systematically mapped the physiographic characteristics of the areas he visited. He reproduced and enhanced many earlier maps and gained considerable renown among Canada’s elite mapmakers.

Ganong turned New Brunswick into his laboratory, interpreting the world around him through scientific reasoning and fact-based observation. He strove to understand the science behind natural phenomena from the formation of waterways to the coloration of rivers, and he strongly believed that the better such matters were understood, the further advanced society would become.

He challenged his colleagues and government representatives to venture into the wilderness in pursuit of scientific discovery and better stewardship of the province’s natural resources. His observations and research revealed problems with forestry practices, and he urged government officials to develop a forestry management policy, claiming:

The greatest natural source of wealth of New Brunswick lies in her forests. These are steadily deteriorating. The public is uninformed and hence indifferent as to their fate. These three facts constitute a forestry problem of the gravest character, and one vastly important to the future of this province.8

Together with long-time friend J.C. Webster, Ganong was instrumental in the development of the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John. Curator Stephen Clayden notes that Ganong’s studies were motivated in part by his recognition of the need to preserve the rapidly disappearing evidence of New Brunswick’s past. He searched for the exact location of historic events and corresponded with numerous colleagues, refining his knowledge of historic sites and First Nations nomenclature. His work also encompassed archaeology, and his contribution on the excavation of a prehistoric shell midden at Bocabec in Charlotte County is considered a seminal archaeological study. The study, led by George F. Matthew marked the beginning of systematic, scientific examinations of shell-bearing archaeological sites in Canada. Ganong believed his work would improve understanding of the province’s unique connections between people and place.

When William F. Ganong died in 1941, Canada lost a great scientist and scholar. No one before or since has studied the natural and physiographic history of the province in such detail. Today, his observations and investigations into New Brunswick’s human and natural history remain relevant. The articles he wrote, the maps he created, the artifacts he collected, and the impressive example of his commitment to exploration and research constitute a precious inheritance. His body of work is an important legacy for the people of New Brunswick, one we should all be grateful for and never take for granted. The following is a tribute to him and to the place where his work began, the New Brunswick wilderness.