HITLER AT THE DOOR

THE INVASION THREAT, JUNE–OCTOBER 1940

BY MID-JUNE 1940 Hitler had overrun six European countries – Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Only the details of the so-called armistice with France remained before he added the better part of a seventh. Britain stood against him as the only European power of any consequence. Hitler had developed a plan for Poland, a plan for Norway, and two for his sweep across Western Europe. Surely he would have a plan for Britain.

The British certainly thought so. The day before the Dunkirk evacuation commenced the Chiefs of Staff warned that a German invasion from Norway, from Eire, or across the Channel could not be ruled out, and that air patrols of the east and south coasts should be instituted immediately.1

It would have surprised the British to learn that in June the Germans were yet to develop an invasion plan. But events in the west had moved in ways not anticipated by Hitler or the German high command. They considered, not without reason, that if the Allied armies were overwhelmed, armistices all round would follow. But the BEF had not been overwhelmed. At times it had been comprehensively outmanoeuvred and at times comprehensively outfought, but it had maintained cohesion and had been evacuated more or less intact, albeit without most of its equipment. With the Channel, the nucleus of an army, the navy and the RAF for protection, with Halifax neutered and Churchill firmly in control, there was no sign from the British that they wished to join the French in coming to terms with Hitler. A rather bemused Führer realised that a plan to subdue Britain would indeed be required but not until France had been conquered.

Only the most rudimentary planning for an invasion of Britain had been undertaken by the Germans by June 1940. In the late autumn of 1939 Admiral Raeder, the head of the German navy, had ordered the naval staff to investigate the problem in case Hitler decided to invade Britain. A special section of the naval staff set to work and came up with plan ‘Northwest’. They thought a landing ‘possible’ but only if the Royal Navy and the RAF had been largely eliminated.2 This paper was not circulated and the navy soon had other matters on its mind, such as the preparations for the Norway expedition. Nothing more was heard of the plan.

Raeder raised the question of an invasion of Britain with Hitler on 21 May, pointing out the ‘exceptional difficulties of such an operation’. Hitler agreed that an invasion would be difficult but made no further comment and issued no instructions.3 There the matter rested until just before the signing of the armistice with the French. Then on 20 June Raeder again raised the matter with the Führer but again got no response.4

Either Raeder’s promptings finally had an effect or Hitler got tired of waiting for British peace overtures, for on 2 July the OKW issued a directive from the Führer’s headquarters entitled ‘Warfare against England’. The directive stated that a landing in England was ‘possible’ if air superiority and ‘certain other necessary conditions’ were fulfilled. The three services were asked for their opinions, keeping in mind that the landing would probably take place on a broad front by a force of 25 to 40 divisions.5

The period – May–June 1940 – in which no plan against Britain was developed has been seen by some as evidence of Hitler’s lack of interest in the whole idea and in any case a period when valuable time was lost. Neither of these interpretations is accurate. Hitler first had to defeat the French armies and establish a safe base along the French coast from which a crucial part of any invasion fleet must sail. This could not be assured until after the armistice with France. Then there was the matter of the French ports. There was never a possibility that an invasion could have been launched immediately after Dunkirk, because all the northern French and Belgian ports had been wrecked. The damage done to Calais, Boulogne, Dunkirk, Nieuport and Ostend was almost total. Docks had to be rebuilt, harbours cleared of sunken ships, cranes brought in to handle cargo, approach roads repaired. This work could not commence before the fighting stopped. In addition, minefields off the ports had to be swept and a myriad of other tasks undertaken to prepare these places for the vast quantity of shipping that would make up an invasion fleet. Even had Hitler possessed a plan to invade Britain straight after Dunkirk he would have been prevented by these factors from carrying it through.

The OKW directive seems to have caught the navy by surprise. Although Raeder had made what little running there had been, he was perhaps trying to alert Hitler to the dangers of the operation rather than hasten its approval. Now he was being required to undertake detailed planning for it. What is evident in these early discussions amongst the naval staff are the difficulties they foresaw in such an operation. They were quick to point out to the other services that invasion was largely a problem of transportation and that the navy could only guarantee the security of the army if the invasion fleet was confined to a fairly narrow front – identified as being between 1.30° west longitude to 1.30 east. They also emphasised the necessity of obtaining absolute control of the air before the operation was launched.6

But with Hitler finally engaged in invasion planning the navy found that many matters passed beyond their control. For example, Hitler insisted that a large number of heavy batteries of guns be placed in the Cape Gris-Nez, Calais and Boulogne area to seal off the flanks of the armada from British naval attack.7 The naval staff indicated that such batteries would be of limited utility. The guns would not possess the accuracy to hit distant, fast-moving ships. Nor would they be able to fire with sufficient rapidity to ‘seal’ a flank.8 On the Führer’s orders work on them went ahead anyway.

Nevertheless, Raeder continued to hammer home the difficulties of invasion to Hitler. At a meeting on 11 July he told the Führer that he regarded invasion as a last resort or perhaps a threat that would push Britain into suing for peace. He concluded by saying that he could not himself advocate the landing.9 Hitler was quick to agree about the difficulty of the operation. He too thought of invasion as a ‘last resort’. In any case, before it could be attempted air superiority must be obtained.10

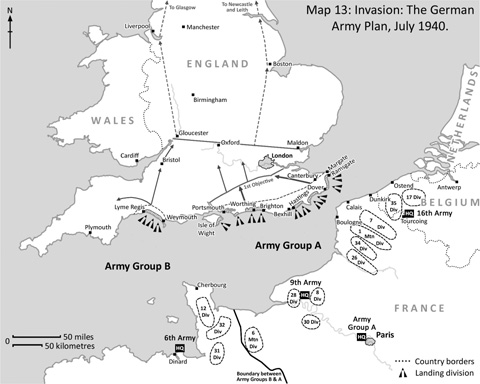

In fact Hitler with one exception accepted all Raeders’ premises but not his conclusion. The operation would be difficult but the question of whether it would prove too difficult would be decided by Hitler. In the meantime planning for it would go ahead. To ensure that planning started promptly, on 16 July Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16, ‘Preparations for a landing against Britain’. It commenced with the usual Hitlerian rhetoric: ‘Since Britain, despite her hopeless military situation, still shows no indications or desire to come to terms with us, I have decided to prepare an invasion, and, if necessary, to carry it out.’11 What followed had more substance. It was the first detailed exposition of an invasion plan. The landing would take place on a broad front from Ramsgate in the east to Lyme Bay in the west. No time was to be wasted. Preparations were to be completed by mid-August. There were the usual preconditions – the operation was to be launched when air superiority had been obtained, when mine-free channels had been cleared, and when the flanks of the invasion could be secured by minefields and coastal artillery. The three services were to draw up plans for their contributions to the invasion and their commanders would relocate their headquarters to be in close proximity to advanced Führer headquarters. The operation was to be called Seelöwe (Sea Lion).12

Joint planning meetings began on the next day but the navy entered them with the greatest trepidation. The naval staff had read the Führer’s directive and commented that ‘the Army regard the whole operation as entirely practicable, undoubtedly lacking knowledge of the difficulties in regard to sea transport and its protection and the exceptional danger to the whole Army’.13

This apprehension only increased when the navy read the army’s draft plan. The army intended to land in three main groups – the first between Ramsgate and Dover, the second between Dover and the Isle of Wight, and the third to the west of the Isle of Wight around Lyme Bay.14 Raeder immediately protested that the navy could not guarantee a crossing on such a broad front. He warned the army that they might lose their entire force and that in any case preparations could not be completed until the end of August or early September. He returned to the question of keeping channels clear of mines and the fact that air superiority was not yet in sight.15

The meeting broke up without any clear direction but Raeder now thought it necessary to produce a detailed appreciation from the navy’s point of view. The paper was decidedly downbeat. He began by noting that the navy was being given a task ‘out of all proportion to its forces’. Raeder then went on to list the difficulties:

•The limited capacity and damaged condition of the Channel ports

•The uncertainty of weather conditions in the Channel

•The fact that as the enemy harbours were defended the troops would have to be landed on open beaches

•Beach landings would require shallow draft ships which would have to be modified to suit these conditions

•The difficulty of sweeping enemy minefields in the Channel and keeping channels swept in the face of enemy naval superiority

•The impossibility, even with minefields and defensive gun fire, of keeping units of the Royal Navy from entering the Channel

•The difficulty of re-supply given the above circumstance.16

Raeder’s gloomy prognosis was well founded. The German navy had been shattered by the campaign in Norway. In July 1940 it had no serviceable heavy units at all. The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had been damaged in Norway and would take some months to repair. The Bismarck and Tirpitz were still under construction and the two Great War vintage battleships were not thought sufficiently strong to fight even the cruisers of the British Home Fleet. Just two cruisers and 13 destroyers were available to escort the invasion fleet. Raeder knew that the British would have at least a dozen cruisers and 40 or 50 destroyers to deploy against him in the first instance, and even greater numbers in the days that followed.17

A meeting between Hitler and Raeder took place to discuss the naval appreciation. Hitler took Raeder’s paper seriously. A recent paper on invasion by Alfred Jodl from OKW had described the operation as being in the nature of an ‘opposed river crossing.’18 Hitler was having none of this. He described the operation as ‘an exceptionally daring undertaking … not just a river crossing but the crossing of a sea which is dominated by the enemy’.19 A force of 40 divisions would be required, as would the subjection of the enemy air force. The Führer accepted Raeder’s point that September would be the earliest possible date for invasion and he asked the navy to work towards that date. Hitler was also worried about the broad front of attack and he asked Raeder to what extent he could guard the crossings to the landing areas suggested in the army plan and when the coastal guns would be ready to protect the flanks.20

Despite Hitler’s misgivings, the navy now knew that it was committed to detailed planning for Sea Lion. The staff met on 22 July and came to the following conclusions. Due to the lack of specialist craft, coastal and river barges by the thousand would need to be assembled to ferry troops across the Channel. Inspections would have to be made of all invasion ports to assess the repairs required to make them functional. The suggested landing places would have to be reconnoitred. Channels in the minefields protecting the British coast would have to be swept. All this would take time.21

Before any of these matters could be resolved the navy was rocked by receiving for the first time the detailed number of troops the army considered would be required for the invasion. The army envisaged an operation in three phases. The first phase would involve the transportation of an initial force of 100,000 men, with appropriate equipment, including artillery and tanks. This force would rapidly be followed by a second wave of 90,000 men, also with heavy equipment. Finally, there would be a third wave of 160,000 men with appropriate equipment.22 In all about 350,000 men plus equipment would have to be landed along the British coast from Ramsgate to Lyme Bay in a period of three days.23

An analysis by the naval staff of these requirements revealed the following: a total of 1,722 coastal or river barges, 471 tugs, 1,161 motor boats and 155 transport ships would be required – in all 2 million tons of shipping. Such a mass of shipping could not be assembled in the invasion ports at the same time because of their limited size. Troops and equipment would have to be brought in relays to the Channel ports from as far away as northern Germany. The distances to be travelled and the necessity for a shuttle service to and from the invasion ports would take time. For practical reasons the waves of troops could not be dispatched daily but would need to be separated into four or five echelons at intervals of two days.24 The army wanted the troops transported in three days; the navy thought more in terms of three weeks for the first wave to six weeks for all three.

The navy also pointed out that the gathering of this enormous amount of shipping would have important implications for the German war economy. It would disrupt inland and coastal shipping to the extent that vital raw materials such as coal might not be available for steel manufacture.25 Twenty-four thousand naval personnel would be required to man the invasion fleet. These could only be found by decommissioning some old battleships and ceasing work on the Tirpitz, and reducing the crews from the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau now in dry-dock.26

Notwithstanding these difficulties, Hitler ordered preparations to continue and on 31 July Raeder could report that invasion plans were in ‘full swing’. The conversion of river and coastal barges for a sea crossing would be completed by the end of August; the conversion of merchant shipping for the invasion fleet was proving ‘difficult’, but progress was being made and the entire fleet should be ready for a landing in mid-September.27

However, after this rather optimistic assessment, Raeder went on to enter some severe caveats about the feasibility of the army plan. A landing in Lyme was out of the question because of its close proximity to the British naval base at Portsmouth. The barges would be required to cross large expanses of water and for this the seas had to be absolutely calm, a distinct problem in the Channel in the second half of September. The transport ships also needed calm weather to transfer their load onto barges for the final run into shore. The small resources at the disposal of the navy made the protection of the invasion force across such a wide front impossible. Raeder strongly suggested to Hitler that operations be confined to the narrow section of the Channel despite the difficulties he knew this would cause for the army, because, after all, the first essential was to get the men ashore safely.28 Raeder’s advice should have told Hitler that the army plan was totally impractical, but the Führer insisted that preparations continue for a landing on 15 September. He would reassess the situation in the light of what the Luftwaffe could accomplish in the next few weeks.29

Hitler’s last point raises one of the oddities of German planning. Most discussions about Sea Lion took place between the navy and the army. The Luftwaffe, in the person of Hermann Goering or any senior air commander, was absent. The air force plan will be discussed in some detail in later chapters but it is necessary to note here that it was never integrated with the planning of the other two services. The Luftwaffe was in essence fighting its own war without relation to invasion. Certainly, the elimination of the RAF was thought to be an essential precondition for invasion by both the army and the navy, but they had other targets they also thought essential to success – the denial of certain ports to enemy warships, the elimination of as many of those warships as possible, the destruction of communications behind the invasion beaches and so on. The Luftwaffe paid very little attention to these requirements. It attacked its own selected targets without reference to the other services. The explanation for this situation is not difficult to find. It seems certain that Hitler and Goering thought that the Luftwaffe alone might bring Britain to its knees. An invasion force would then only be required to sail across the Channel and occupy a defeated country. In this sense the Luftwaffe might solve all the difficulties that were starting to emerge between the army and the navy in their planning sessions.

Essentially their differences boiled down to the broad front versus the narrow front approach. The navy kept insisting that it did not have the craft to protect the flanks of a landing on such a broad front. The army replied that only by landing on a wide front could its divisions deploy for an effective advance after the landing. In the coming weeks many meetings between the services were held without a resolution of these issues. A particularly acrimonious exchange took place on 7 August. Franz Halder stated that the navy’s plan to land only on a narrow front each side of Dover was unacceptable. The army must land at least as far west as Brighton because of the difficulty in deploying in the low ground inland from the Dover–Folkestone area. He concluded by saying: ‘I utterly reject the Navy’s proposal from the point of view of the Army I regard the proposal as complete suicide.’30

Only Hitler could resolve these differences, but he preferred to keep his options open. While telling the navy that he understood the difficulties of protecting a landing on a broad front, the Führer ordered preparations to continue for just such an operation.31 The day after this decision and in response to a desperate plea from the navy for a definite plan to be developed, a compromise was put forward by Jodl at OKW. The operation would be on a narrow front with the addition of two forces to outflank the British divisions between Dover and London. On the left a force of 4,000–5,000 men would be transported from Le Havre to Brighton while on the right a force of 5,000 paratroopers would be dropped in the Deal–Ramsgate area. In preparation for the landings an all-out assault would be made by the Luftwaffe on London to panic the population and block the roads the British intended to use to bring up reserves (Map 14).32

Despite some minor adjustments, this was the basis of the final plan. On the right, elements of six divisions from the 16th Army would land between Folkestone and Beachy Head. They would then spread out and seize an initial bridgehead between Hadlow and Canterbury. At the same time, on the left, a force of three divisions from the 9th Army at Le Havre would seize a line from Cuckmere to Brighton and push inland to extend the bridgehead. The paratroopers were eventually given the tasks of landing north of Dover. The initial force with suitable reinforcements would then advance to a line running from Gravesend to west of Portsmouth. Mobile forces would then move to the west of London to isolate the capital and then advance to a line north-east of London, from Maldon in Suffolk to the Severn Estuary in the west.33 The troops would be landed in four waves. In the first wave 50,000 men from the nine assault divisions would be landed in the first two hours. The remainder of these divisions (75,000 men) would follow two hours later. After that the plan was to land an additional two divisions every four days so that within four weeks a total of 16 divisions would be ashore. A further nine divisions would constitute the remainder of the third and fourth waves and be ashore by S-Day plus six weeks.34

Further discussions and meetings between the Führer, the navy and the army took place in September and October, but this remained the final plan. This raises the question: on the evidence we have, was Hitler serious about Sea Lion or was he, as some historians have suggested, just using the preparations for invasion as a means of exerting pressure on Britain to make peace?

The scale of preparations for Sea Lion makes it extremely unlikely that the operation was merely a giant bluff. It was noted earlier that the collection of shipping placed sections of the German war economy under great strain – hardly an indication that Hitler was bluffing. Moreover, consider the number and scale of the meetings held to thrash out the final plan for Sea Lion: between 25 May and 19 September no fewer than 44 meetings concerning Sea Lion were held – about one meeting every two and a half days. And these meetings often tied up the naval staff, OKH, OKW and the Führer himself. In fact Hitler attended 12 of the 44 meetings. The Führer would not have wasted his time if he was merely intending to deceive. The acrimony resulting between the navy and the army as they fought for their respective plans at these meetings was surely hardly the result of mere posturing. Furthermore, the level of detail contained in the plans – the consignment of particular divisions to particular beaches, the precise assembling of craft at the appropriate ports, the difficulties of landing armour over open beaches and a myriad of other matters discussed – does not suggest that the staffs were merely going through the motions. There are many other indications that Hitler was indeed serious about an invasion. The instruction to the SS to compile a handbook on Britain for the invasion forces looks serious enough. So does the list of persons to be immediately arrested by the Gestapo, with which the handbook concludes.35

Much of the myth of Hitler’s invasion ‘bluff’ can be traced back to those who have suggested that the Führer thought well of the British and had no wish to conquer them. This is nonsense. Hitler hated the British and there is little question that had he succeeded in his plans, Great Britain would have been subjected to the reign of the Gestapo, the SS and his other instruments of oppression – as had happened in Western Europe. Indeed, this occupation might in some ways have been harsher than that imposed upon the French, for of all his contemporary enemies Hitler feared the British the most. In this scenario it is impossible to imagine that he would have allowed even the pseudo-autonomy that the Vichy-controlled section of France was granted. Once Britain was in Hitler’s grip he would surely have crushed it out of existence.

* * * * *

How well would the British have withstood a German invasion had it been launched? What anti-invasion plans had the three services made and what progress had been achieved from June to September in implementing these plans?

Let us start with a discussion of the state of the army after Dunkirk. It was desperate. After the evacuations from Dunkirk and western France there were just over 500,000 fighting men in Britain, but they lacked equipment of all kinds.36 The divisions possessed just 295 of the 25-pounder guns as against the establishment figure of 1,368.37 For Matilda tanks (the only tank of proven worth against the Germans) the establishment figure of 1,480 compared starkly with the actual number of 140.38 All other equipment was in short supply. There were several score of Great War vintage 18-pounder guns and some 4.5-inch howitzers, but there were few anti-tank guns, armoured cars and mortars. There was not even a rifle for every infantryman.39 The Army Council noted that in the crucial invasion area between the Wash and the Isle of Wight just five divisions were spread along the coast and there were only three in GHQ Reserve. These under-equipped units would surely have been brushed aside had the Germans got ashore in numbers in this period.

The commander-in-chief of this force was General Ironside, replaced by General Dill as Chief of the Imperial General Staff but perhaps now in a more appropriate role. In these early days he had few resources to work with and his anti-invasion plan reflected that situation. Ironside issued a paper on ‘Preparations for Defence’ on 4 June. Some 50,000 anti-tank mines were to be placed opposite the most likely landing beaches along the south and eastern coasts. Another 200,000 of these were ordered to cover all beaches in the area from the Wash to Portsmouth. Work commenced on rendering useless any potential drop zones for parachutists and gliderborne troops. Road bridges near ports were prepared for demolition and roadblocks were established to slow the progress of enemy armour. A total of 47 batteries of 6-inch guns were installed near likely landing places as were some batteries of anti-tank guns. Guns were also fitted to lorries to provide at least some mobile artillery.40 Most of these units were in place by mid-June.

Meanwhile, inland, what became known as the GHQ Line was developed. This position stretched from south of London to the Midlands and followed defensive positions such as waterways, canals or the reverse slopes of hills. Essentially it consisted of an array of anti-tank obstacles placed to intercept any German armour that broke through the coastal crust into the interior. The ‘line’ was supplemented by a number of forward positions consisting of anti-tank guns, machine guns and infantry that were designed to confine, break up and delay enemy forces advancing from the coast before they reached the GHQ Line. This would give Ironside time to deploy mobile columns, consisting of what few armoured cars, tanks and truck-borne infantry he had in GHQ Reserve, against any German lodgement areas.41

On paper, the manpower at Ironside’s disposal looked adequate. The number of fighting men had increased from 500,000 at the end of May to 1,270,000 by mid-June. But over half of these were still in training. This left just 595,000 trained troops and of these 275,000 had just returned from France and were almost entirely without equipment.42

Despite Ironside’s efforts the whole defensive position of the British army was very weak. The roadblocks could easily have been circumvented by armoured vehicles as could the stop lines. Many of the anti-tank positions in the GHQ Line existed largely on paper. The mobile columns were few in number and deficient in armour. Yet it is hard to see what other dispositions Ironside could have made given the state of training of his force and its lack of equipment.

Churchill soon tired of what he considered Ironside’s conservative approach and on 20 July replaced him with General Brooke. This was a harsh judgement given the little with which Ironside had to work. However, there is no doubt that Brooke was a good choice and a better leader if an invasion was to take place.43 He embarked on a lightning tour of his forces, finding them, as a whole, not very impressive.44

Brooke was also unhappy with the static nature of the defences and was no doubt relieved to receive a note from Churchill assuring him that the navy now had sufficient vessels at sea at any given time to rule out a surprise attack on a large scale. In this circumstance he thought Brooke could withdraw some of his forces back from the coast for training.45 Brooke, who envisaged only a light defence on the beaches, was only too happy to comply.

With the army growing to just over 900,000 reasonably well-trained men (including one Canadian division and two Australian brigades), the main constraint continued to be equipment.46 The number of 25-pounder guns in the country had only increased from the 295 in June to 368 in August.47 Matilda tank numbers had only increased from 140 to 216. The 200 lighter cruiser tanks were also well short of the numbers required.48

Gradually, though, the state of the army improved. In early September the five divisions that in June had held the coast between the Wash and the Isle of Wight had increased to eight, and in addition there were two brigades and one brigade group in the area. And in the close vicinity of London were another three divisions, two armoured divisions and two brigade groups. Included in these forces were the 1 Canadian Division, the New Zealand Division and the Australian Brigade group, so an invasion would have involved a Commonwealth response.49

Brooke, however, still took a pessimistic view of the situation, regarding only 50 per cent of his divisions as fit for any form of mobile combat.50 The responsibility of command weighed heavily upon him and he had been seared by his experiences against the German army in France. On the positive side his dispositions were well placed to oppose the most likely German lodgement areas and by September the nucleus of the old BEF was reasonably well equipped. For example, by then each of its 12 infantry divisions had 80 guns of all types, well below the establishment figure but at least able to put down a reasonable volume of fire.51 And each month that passed saw the munitions factories produce another 220 field-artillery pieces.52

However, in the event of a major invasion there is no doubt that Brooke’s pessimism would have been well founded. Had the Germans managed to land their projected number of 100,000 troops plus armour along the southern English coast in the first few hours of an invasion, the British forces would have had a difficult time dislodging them. But the vital question was whether the Germans would have been able to land such a force in the light of British naval superiority.

The Dunkirk operations had taken their toll on the navy. Of the main anti-invasion craft, nine destroyers and five minesweepers had been sunk, and 19 destroyers, one anti-aircraft cruiser and seven minesweepers damaged.53 In addition, over the next few months some powerful naval craft had been diverted from home waters for other purposes. In July, after the French had concluded their armistice with Germany, concerns had arisen in the War Cabinet about the strong French Fleet in the Mediterranean. The naval action that eliminated much of the French Fleet has already been dealt with, but here it is important to note its effect on the Home Fleet. To build up a force at Gibraltar strong enough to deal with the French, first the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and then the battlecruiser Hood followed by the battleship Valiant had been dispatched from the Home Fleet to the Mediterranean.54 So for some weeks in July the commander-in-chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Forbes, was deprived of three of his best capital ships.

Another diversion occurred in September when an expedition sailed to West Africa to assist the Free French in claiming the colony of Senegal and its capital and naval base, Dakar. A successful action, so it was thought, might rally the entire French Empire to the Allied cause and consolidate the position of General de Gaulle. It was also feared by the Admiralty that enemy forces might use Dakar as a base from which to interrupt British convoys, though this seemed to overlook the difficulty that enemy ships would have had in reaching them across waters dominated by the Royal Navy. In fact there was never an attempt by the Germans to hazard such a move. Nevertheless two battleships, an aircraft carrier, three cruisers and 10 destroyers accompanied the expedition and were therefore absent from Gibraltar from 7 September until early October.55 In the event the expedition was a total failure. French forces at Dakar, including the battleship Richelieu, put up such a stiff fight that the expedition was forced to withdraw. In retrospect the decision that deprived the Home Fleet of reinforcement by such a powerful squadron seems bizarre. The fact that the danger was noted by the Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff before it sailed cut no ice.56 The operation was approved by Churchill. He was perhaps fortunate that the failure at Dakar was swift and came at a time when Hitler was reconsidering the whole question of invasion.

In the meantime the navy honed its anti-invasion strategy. This process was not without some friction. Admiral Forbes had strong views on the use of his heavy vessels in the event of an invasion. He thought that they should remain at Scapa Flow to counter an enemy attempt to break out into the Atlantic or invade Eire.57 The Admiralty staff thought that at least some heavy units should be placed further south for anti-invasion duties.58 After an acrimonious exchange of telegrams the naval staff won. Forbes would base a force of battlecruisers at Rosyth ‘as soon as possible’.59

There was further dissent from Forbes. When told about the plans of the army and the RAF to counter invasion, he seized on the strength of the RAF to conclude that an invasion was extremely unlikely.60 As it happened, Forbes was probably correct, but such a conclusion was not his to make. It took a minute from the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff to pull Forbes into line. He was told that his ships should be optimally disposed to meet a seaborne attack61 and to act on the basis that an invasion was likely.62

This was the end of that matter but another soon arose. Forbes, it was now revealed, regarded German warships as his main target should an encounter occur in the south, rather than any transports carrying the German army towards the English coast. This time it took just a single acerbic minute to redirect his policy. The Admiralty informed him that ‘in case of invasion repetition in case of invasion … attack on enemy transports and landing craft becomes primary object, enemy warships being dealt with only in so far as they interfere’.63

Despite these distractions, the navy plan was rapidly developed. Warships would attack the German invasion fleet before it departed, on the way across and at the point or points of arrival. In the first phase the navy assumed they would have some advance intelligence of the gathering enemy force from aerial reconnaissance and observation from patrolling ships. They would attack these forces with naval craft where possible and call on Bomber Command to assist.

When the force was under way the navy would rely on four flotillas of destroyers (about 40 ships) assembled between the Humber and Portsmouth. These could be reinforced by battleships based at Plymouth and cruiser squadrons in the Thames Estuary and the Humber, minesweepers, corvettes and any other small craft with offensive capability. Any enemy force that effected a landing would be attacked by small inshore craft while the main strike force would attempt to interdict any enemy reinforcements in the Channel or the east coast.64 And once the Admiralty had won out over Forbes, the heavy units of the Home Fleet would be in close attendance as reinforcements where required.

The other aspect of planning that concerned the navy was the seizure of a port by the Germans. Only at a port, it was considered, would the enemy be able to land tanks in any number and considering what had happened in France it was imperative to keep this number to a minimum. During June naval officers were dispatched to all major ports between Aberdeen and Swansea. Their main task was to develop a plan to immobilise those sections of the ports useful for offloading tanks and other vehicles for a period of 7 to 10 days, by which time it was thought that the army would have dealt with the invaders. Then the ports could resume their normal duties. These plans were well in hand by the end of the month, but the finetuning of the planned demolition works was problematic. To close certain sections of a port temporarily would have been difficult to calibrate – putting the entire port out of action was much easier. Clearly some ports would have been totally demolished on invasion and out of action for much longer than a week or so. But on the positive side it is very doubtful whether a usable port could have been seized by the invaders. In all likelihood they would have been forced to land tanks, trucks and other vehicles over open beaches.65

To make ports even more difficult for an enemy to use, blockships were to be sunk at the entrance to harbours, making it hard for enemy follow-up forces to enter. These too were supposed to be temporary arrangements, with the ships being lifted out of the channels when the threat was over. As with demolition, it is doubtful whether this would have worked as smoothly as anticipated. Clearly many English harbours would have been out of action for some time, but the main purpose of denying the ports to the enemy had an excellent chance of success.66

This basic plan remained in force throughout the invasion period. By August a truly formidable array of anti-invasion craft was in place. At Scapa Flow were two battleships, two aircraft carriers and a battlecruiser, with attendant cruiser, destroyer and minesweeping squadrons. Further south were elements of 18th Cruiser Squadron at Rosyth where there were also 13 anti-aircraft destroyers. On the Humber were six destroyers, while at Harwich there were 10 destroyers, three corvettes and 13 motor torpedo boats. On the Thames estuary at Sheerness were seven destroyers. Along the south coast were three more destroyer flotillas (just over 20 ships), a collection of motor torpedo boats, an aircraft carrier, and a miscellaneous collection of other warships. There was also a strong force of destroyers based at Liverpool and the Clyde, and more fighting ships at Chatham, Portland, Hull, Greenock and other ports. Nearby were several flotillas of submarines and the armed merchant vessels of the northern patrol. This is not to mention hundreds of armed sloops and patrol vessels scattered around the coast but concentrated mainly along the eastern and southern coasts. Moreover, at Gibraltar just 36 hours away were the two battleships, two battlecruisers and an aircraft carrier from Force H.67 There were some weaknesses. There was still only cruisers based at Rosyth and the attentions of the Luftwaffe had forced the destroyer flotilla at Dover to redeploy to Harwich or Portsmouth and be replaced with a few motor torpedo boats.68 But despite these weaknesses this was a mighty force, especially at a time when the Germans had not a single heavy ship available, just one heavy cruiser, 13 destroyers and a few motor torpedo boats.

In the event this force was never required to thwart an invasion, but there were some alarms. On 13 August (Eagle Day for the Luftwaffe) the increased aerial activity and a German feint with a collection of merchant vessels towards the northern coast brought the Home Fleet to two hours’ notice.69 Then, on 7 September, the code word for invasion, Cromwell, was issued. The heavy ships of the Home Fleet put to sea, raising steam for 24 knots. An invasion was expected imminently and the force with its attendant cruisers and destroyers headed into the North Sea. The Admiralty advised Forbes that the scheme to immobilise the ports should be brought to the shortest possible notice.70 But it was a false alarm based on the movement of German barges towards the Channel.71 The last major alarm occurred on 13 September. The Admiralty signalled Forbes:

All evidence points to attempted invasion on a large scale and we must expect that Germany will throw everything into it including every capital ship they can make available. Taking everything into consideration following dispositions of capital ships is considered necessary: (i) Nelson, Rodney and Hood at Rosyth; (ii) Repulse and 8-inch cruisers at Scapa; (iii) Revenge at Plymouth. It is realised that this disposition is weaker than present one for dealing with operations against Iceland or Ireland, but this is accepted … Request you move Nelson and Hood to Rosyth as soon as possible.72

Nothing came of this, but it provides evidence that in an emergency the deployment of Forbes’ heavy ships would be decided by the Admiralty.

The air force plan was developed with just one hitch. The Admiralty and the RAF seemed to have different priorities for fighter aircraft during an invasion. At an inter-service meeting Admiral Drax, commander-in-chief of Nore Command, asked the RAF what role Fighter Command would play in the invasion. Group Captain Lawson, the RAF liaison officer, replied that its primary object would be ‘the destruction of the invading enemy aircraft’.73 This alarmed Drax. It seemed that the RAF would attack the enemy warplanes and leave his warships unprotected. In the end it was agreed that Drax would contact Hugh Dowding of Fighter Command to clarify the position.74 Drax lost no time, writing to Dowding at the end of the meeting. He told him that the anti-invasion forces would be mainly destroyer flotillas which would be very vulnerable to air attack and that ‘they will be defeated by the enemy bombers if our fighters are not on the spot to attack them’.75 Dowding replied that he considered the whole issue of such importance that it must be discussed by the Chiefs of Staff Committee, but his own opinion was that the fighters would indeed cover the navy’s warships while the bombers attacked their transports.76 Not surprisingly, when the issue came before the Chiefs of Staff they agreed with Dowding. The navy would be protected by Fighter Command.77

With that issue decided, the air force developed its plan. Its first duty was to fly regular reconnaissance flights to give early warning of concentrations of enemy shipping in ports from the Baltic to Cherbourg. This task fell to Coastal Command. Should such concentrations be discovered, Bomber Command was to bomb them while continuing to bomb communications between Germany and the invasion ports. When the invasion commenced, bombers escorted by fighters would attack the enemy transports. The majority of fighters would provide protection for the navy against attack by enemy aircraft. Enemy troops would be attacked on the beaches and any counter-attack forces be given fighter protection. If the enemy should land, the priorities established by Fighter Command were:

1.attack dive-bombing aircraft operating against naval forces

2.attack tank-carrying aircraft (in fact the Germans had none of these)

3.attack troop-carrying aircraft

4.attack enemy bombers

5.attack enemy fighters

On 8 July 1940 Britain had 720 serviceable modern single-engine fighters and about 500 bombers with which to carry out these duties.

That the British armed forces would be kept up to the mark and that their chiefs would undergo constant prodding on almost every critical issue regarding invasion was the self-imposed task of the Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. Churchill kept the closest possible oversight of invasion preparations. So ubiquitous were his demands that General Brooke feared that should the invasion come, the Prime Minister would use his position as Minister of Defence to assume supreme command of all the armed forces.78

Churchill demanded information on all aspects of invasion planning. In just one memorandum he asked the Chiefs of Staff to provide him with statistics on enemy tank-carrying barges, urged Ironside to hold more troops in reserve, sought assurances that the destroyer forces would attack the barges ‘with gusto’, and came to the sensible conclusion that ‘the power of the Navy remains decisive against any serious invasion’.79

One of his abiding obsessions was to establish batteries of heavy guns near Dover to strike at an invasion fleet and to strike back at the enemy batteries erected at Hitler’s insistence around Boulogne and Calais. In fact such guns were not very useful. At these distances they would have to be fortunate to hit stationary targets more than twice in a hundred shots, by which time the barrels of the guns would have been worn down to such an extent as to require replacement. Nevertheless, Churchill insisted that they be installed. He wrote to Ismay on 21 June asking for a report and followed this up with requests as to progress on 7 July, 15 July and 5 August.80 On 8 August he was pleased to hear that a 14-inch gun had been mounted but then fretted because there seemed to be no plan to attack the German guns systematically.81 On 1 September he was ‘deeply concerned’ that the German guns could not be engaged until 16 September and he demanded a more rapid response.82 In fact firing began the day before and continued sporadically throughout the invasion period. Little damage was done in these long-range duels, either to shipping in the Channel or to the enemy batteries. Air power was now the key to controlling the Straits of Dover.83

Other interventions by Churchill were more useful. He decried the many papers produced by various services suggesting that the Germans might strike at England through an invasion of Eire. In response to one such paper he informed Ismay that ‘it is not at all likely that a naval descent will be effected there’. He thought it might be possible for the Germans to transport some paratroopers to southern Island but that in any case ‘nothing that can happen in Ireland can be immediately decisive’.84

Churchill’s views on Ireland, as well as calming the Chiefs of Staff, had strategic consequences. In June the military had decided that two fully equipped divisions should be sent to Northern Ireland to counter any German moves against the south. Churchill deplored this action. At the time fully equipped divisions were rare and he wanted them to remain near the shores most threatened with invasion.85 Nevertheless, the Chiefs of Staff decided to send Montgomery’s 3 Division to Belfast. Somehow Chamberlain got wind of this scheme and brought it to Churchill’s attention. The matter was discussed in Cabinet on 2 July. Representing the Chiefs, the Chief of the Air Staff said the movement of the division had been ‘carefully weighed up’ and that they had decided to send it because ‘the threat to this country resulting from a German invasion of Ireland is a very serious one’.86 Churchill strongly disagreed and in the end the War Cabinet ‘agreed that the Third Division should not be sent to Northern Ireland’.87

A second intervention by Churchill prevented 2 Canadian Division being deployed to Iceland. Three battalions of this first-rate formation had already been dispatched when Churchill found out and he ordered Anthony Eden to stop the whole process as the troops were needed in England. Needless to say the Canadians remained.88

Even after Brooke’s appointment as commander-in-chief of Home Forces, Churchill was not content just to read reports on the progress of re-equipping the army. He constantly toured divisions and interrogated commanders about their requirements. One such visit paid dividends. Montgomery’s 3 Division was occupying a key sector of the southern coast but it was strung out along the beaches and had no transport for those reserves held back to intervene at the invasion points. Montgomery asked Churchill for civilian buses to be supplied for this purpose. The following day Churchill minuted Eden to request the buses. They were delivered with all speed.89

Indeed, there was hardly an aspect of the invasion problem that Churchill did not investigate. He was concerned that desperately needed rifles coming from the US were adequately convoyed, that the anti-invasion destroyers had sufficient ammunition, that tank production was lagging, or that fog might prevent the navy from responding to an invasion with appropriate vigour.90

One matter that was to cause much controversy later was Churchill’s position on the use of poison gas on an invading army. As early as June he asked Ismay to report on what stocks of mustard gas and other variants Britain held and whether the substances could be delivered by guns, air bombs or by aerial spraying. He asked for output by month and concluded that ‘there would be no need to wait for the enemy to adopt such methods. He will certainly adopt them if he thinks it will pay.’91 In other words Britain would in the event of an invasion use what gas it had on the German army the minute it touched ground. The fact was, however, that there would have been little gas available. There were few gas shells, so the main method of delivery would have been to spray the gas (which was in the main mustard gas) from the air.92

The modern outcry about this decision takes little account of the situation facing the British in 1940. Certainly they could be confident in the superiority of their navy and in the prowess of the RAF, but their army was outnumbered and out-munitioned by the Germans and in general was of inferior skill. If the enemy army gained a foothold in Britain the situation might rapidly become desperate. If poison gas appeared necessary to keep the Nazi army at bay, then there was no doubt that it would have been used. When Churchill spoke of victory at all costs he meant it.

To sum up, by September the British army was well short of its establishment of guns and tanks but was in reasonable shape and was well led. The RAF was also well led and had first-rate fighters available to attack an invasion force. The navy was well led at the lower levels (e.g. destroyer flotillas) that would have played a key role in thwarting an invasion, and in numbers was far superior to the Germans.

The question remains whether the German invasion plan as finally developed could have succeeded. The answer surely must be a resounding no. There has been much futile debate in Britain in recent years about whether the navy or the air force actually thwarted Hitler’s designs. There is in fact no need to designate any service as being the vital factor in preventing the German fleet from sailing. Had it sailed, the navy, with more than adequate means of reconnaissance, would have had sufficient warning that the enemy was coming. The arrival of the destroyer flotillas, protected by Fighter Command, could only have had one result. Most of the German barges and their tugs would have been sunk. One calculation suggests that the bow of a destroyer in close proximity to a barge would have created a wave large enough to sink it. Therefore, many destroyers could have performed their anti-invasion role without firing a shot. And in addition to the destroyers the navy also had available cruisers, armed trawlers, corvettes and many other craft. Behind this force stood the heavy units of the Home Fleet, which Churchill would certainly have ordered into action if an invasion was under way. The merchant ships, transferring their cargoes to barges in the Channel, would have been the easiest of targets. It is doubtful whether any could have survived a sustained naval attack. And then there was the matter of the six weeks that the Germans calculated they would require to reinforce the initial waves of attacks. It seems beyond doubt that if any of the second, third or fourth waves had left port, they would have been sunk at some stage during the crossing. In fact, because of the almost certain destruction of the first wave, it is highly unlikely that they would have ventured out. It is of course true that the Luftwaffe would have exacted some toll on the British ships. Some destroyers and other ships would have been sunk by the Germans. But the fact remains that there were just too many British ships for the Germans to forestall the carnage that would have followed.

The inescapable conclusion must be that the German command was well aware of these scenarios. The forces available to them were indeed formidable but not appropriate for an invasion of Britain. The failure to capture the BEF, the failure to subdue the RAF, and the woeful German inferiority at sea were the factors that led Hitler to call off the operation. He would finally turn to the only expedient remaining to him, an attack on the British people. If he could not invade, if Churchill would not see reason, then perhaps a terrified and cowed population would decide the issue.