During December 1940 Pete met Lee Hays and his roommate Millard Lampell, who would quickly form the Almanac Singers. “Heard about a man named Lee Hays who was also trying to get a book of union songs published,” Pete later wrote. “It seemed sensible to get together. I knocked on his door, met his roommate, Mill Lampell, too. A few weeks later the three of us were singing for left-wing fundraising parties around the Five Boroughs.”* Hays (1914-1981), born in Arkansas, had worked with Claude Williams at Commonwealth College in Mena, Arkansas, but fled the South due to his left-wing politics and arrived in New York City, where he met Lampell (1919-1997). The latter had grown up in New Jersey, attended college in West Virginia, then moved to New York to become a journalist.† The trio, soon named the Almanac Singers, attracted others as they supported labor unions, civil rights, and the peace movement (then popular with the Communist Party because of the 1939 Nazi-Soviet neutrality pact). The article by George Lewis, commenting on their performing topical songs before the League of American Writers, was perhaps the first to mention them in print. Pete now used the surname Bowers to protect his father’s government position. The article mentions Woody Guthrie’s recent peace song “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?” as well as Alfred Hays/Earl Robinson’s catchy song about the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) bard “Joe Hill.”

SOURCE Daily Worker, March 24, 1941.

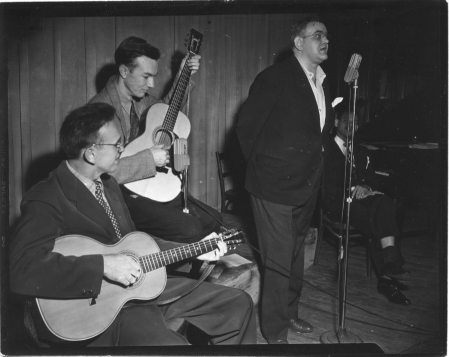

Earl Robinson, Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, early 1940s. Daily Worker/Daily World Photographic Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University.

The Almanacs, a loose group of musicians, would soon include Peter Hawes, his brother Baldwin “Butch” Hawes, Josh White, Arthur Stern, Bess Lomax (Alan’s sister), Woody Guthrie, Agnes “Sis” Cunningham, and assorted others. In April 1941 they raised $300 in a house party to fund an album of recently composed peace songs, Songs for John Doe, released by Keynote Records on the Almanac label. An April article in the New York Times made no mention of the Almanacs’ controversial politics, but presented them as students of American folk music. The group next released a pro-labor album for Keynote, Talking Union, as well as two albums of traditional songs, Sod Buster Ballads and Deep Sea Chanties. Over the summer Pete, Mill, Lee, and Woody appeared at union rallies and meetings throughout the country. They had now abandoned their peace songs, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June, but the taint of being communists, meaning un-American, would escalate. A Time article in September, while reminding readers of their following the “Moscow line,” seems rather positive about “the four young men who roam around the country in a $150 Buick and fight the class war with ballads and guitars …. The three discs of Talking Union, on sale last week under the Keynote label, lay off the isolationist business now that the Russians are laying it on the Germans. One of the Almanacers’ ablest vocalists is Pete Bowers, and he gets to sing the punchiest of the six numbers, the title song of the collection.”*

At a recent meeting of the League of American Writers Theodore Dreiser heard Pete Bowers and Lee Hays, the Almanac Singers, sing ballads from their endless repertoire. When they had finished singing, Dreiser commented, “if there were six more teams like you, we could save America,” … Pete Bowers, who prepared for college at a Connecticut Preparatory School, and attended Harvard, developed an interest in the people’s music and has for the last two years been traveling through all sections of the country learning the songs that America sings ….

They [Hays, Bowers, and Millard Lampell] are not a part of the current ballad fad; they feel a definite responsibility for the cultural and political standards of their work; and toward the end of creating valid material they have made through analytical studies of the source of a people’s culture as it is found in all contemporary forms of proletarian expression. As they say, there is a tremendous significance in the fact that their audiences repeatedly call for “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?” and “Joe Hill.” Audiences want this form of music, but there are too few examples among which they can choose. The Almanac Singers hope to provide a larger repertoire for all ballad singers. Their task is to write ballads that grow out of the immediacy of our problems today, rather than to repeat performances of those songs which have, to be sure, solid historical connotations, but nevertheless are “standards” and have lost much of their meanings today.