reliable, resilient, marvellous but sometimes the dumbest organ of them all

MY FATHER ARON GALLER died at 6 a.m. on 2 May 1990, the day before my mother’s birthday. He was 77 years old. As he lay dying on the floor, his head in my mother’s arms, he looked startled and asked, ‘What’s happening, Zosia?’ Then he was gone.

Helpless, distraught and furious, my mother tried to bring him back to life by screaming and punching him. Needless to say it didn’t work. His heart, the dumbest organ in the body, had stopped forever.

My mother called our GP, who came immediately. Too late to help Dad, she rang me as I was waking up to go to work at Middlemore Hospital in South Auckland.

I will never forget that phone call because of the guilt that welled up in me as soon as the phone rang. It was as though I already knew what had happened. You see Dad’s death was not a surprise to me. We’d been talking on the phone a lot in the past few days and he had described to me what we in the game call crescendo angina—an escalation of chest pain that commonly leads to a heart attack and sometimes cardiac arrest.

My father was a good man. He came to New Zealand from Poland as a refugee in 1947. A lawyer by training he did what we Jews do well—he went into the schmutter business, in Dad’s case, women’s clothes.

When he first arrived in New Zealand he worked with his older brother Oser manufacturing women’s coats, but after a near fatal fight they went their separate ways; Dad to the corner of Adelaide Rd overlooking the Basin Reserve. There he established a small manufacturing company and employed a dozen seamstresses, most of them, like him, refugees from Eastern Europe.

Dad had lived through interesting times, and he was kind and generous to a fault. He loved my mother more than anything and she depended on him for almost everything. Despite all of that his heart decided to stop and with that so too did the flow of blood and oxygen to all parts of him.

No, this was not a surprise. It was a consequence of many years of heart problems, which my brother and I jokingly blamed on my mother’s cooking—especially her baked Polish cheesecake—and the second-hand smoke generated by her chain smoking. The cheesecake was a culinary IED; enough to give me angina just knowing it was on the kitchen table. Her other delight, the less poisonous Polish coffee cake, was simply too irresistible to leave alone and in the end must also carry some of the blame for my father’s downfall.

My mother, Zosia Galler, was a socialite and the Polish coffee cake was baked fresh most days to feed the constant run of visitors to our house in the Wellington suburb of Wadestown. Mostly they were Eastern European friends of my parents who loved nothing more than a cigarette, a chat, coffee and cake. What was left over from the previous day’s cake was eaten by my father. Every morning, elegantly attired in his silk dressing gown and hairnet, he could be found, knife in hand, dissecting out and eating the cake’s rich veins of chocolate before demolishing the cake itself.

Dad’s eldest brother, Oser, was married to Aunt Nina. She was also a heavy smoker—in her case not the mild Peter Stuyvesant or Rothmans that my mother loved but unfiltered Capstan Plain cigarettes. Oser had similar eating habits to those of my father. He loved picking from dishes in the fridge or on the stove but his penchant was for the savoury. He too died from heart disease. Maybe that will be my fate as well, but on average my family history suggests Zyklon B, the gas used by the Germans in the Second World War to exterminate so many Jews, as the most likely cause of my demise.

In my first year at med school in Dunedin, groups of us were assigned a cadaver. They were laid out on two rows of stainless steel tables that ran the length of a large, whitewashed, highceilinged room. Along both sides of the room were floor-to-ceiling windows, between them hung painted scrolls illustrating various parts of the human anatomy—the arterial system of the body with its blood full of oxygen, vessels coloured red; the veins of the body, its blood depleted of oxygen by the tissues of the body, coloured blue; the brachial plexus, nerves coloured yellow coming from the neck, going to the arm; the Circle of Willis, the beautifully designed arterial system at the base of the brain coloured red, and much more. In one such space was a floor-to-ceiling painting of the heart along with various drawings illustrating its chambers and valves, and one even showing the wiring system that accounted for the metronomic reliability that is its hallmark.

Nowhere was there a painting to illustrate what is commonly attributed to the heart: love, tenderness, and the range of emotions we all associate with it. Nowhere in the dissection of that organ did we see any hint of them either. It was an exercise that many in my group, still young and idealistic, found disappointing and sobering. Our heart was brown and rubbery, and smelled of formalin. Standing there in the dissection room, it was just another dead organ from the dead body in front of us. It was hard to believe that it could inspire such whimsy, let alone once have been that complex mix of flesh and blood; a pump, that slavishly served the brighter parts of us—our brain, liver and kidneys.

Although marvellous and reliable in some ways, the heart is the dumbest organ in the body—after all it keeps going in many people who might be better off dead, and stops in good people in the prime of their lives. It’s an essential without which we are no more and, unlike our eyes and our kidneys, we have only one. There is no back up, no seagull engine for when the main motor fails, not even a set of oars. Because the health of our one and only heart is so imperative to our existence, modern society has made a massive investment to know everything there is to know about this essential bit of kit.

As a result of that, we now have expertise and technologies that are simply staggering. For the tiny baby born in Samoa with Tetralogy of Fallot—a complicated congenital abnormality of the heart that would lead to certain death if left untreated—treatments in first world health systems now exist.

Thanks to the skills of the local paediatricians, Makalita was diagnosed early and transferred to New Zealand where the four structural defects that make up the Tetralogy were repaired. That we can do that successfully in such a tiny baby will always amaze me.

As we move through the generations, there is a long list of other cardiac ailments any of us might be unlucky enough to acquire, each one of them countered by a range of increasingly effective treatments. As clever as we are though, the original design of our heart—G-d-given or refined over millions and millions of years—has proven to be impossible for us humans to match, even for those living with the gift of someone else’s. This is sobering territory and a lesson for those looking for cures to their ailments, aches and pains in the deeds of men, because what’s on offer from our best and brightest might not actually give you what you expect or want.

As an aside, the custom of substituting the word ‘God’ with G-d in English is based on the traditional practice in Jewish law of giving G-d’s Hebrew name a high degree of respect and reverence. In short, this is a sign that the concept of G-d cannot be merely encapsulated in a word. Although I am not a religious man, for me, the substitution of the hyphen for a vowel adds a sense of mystery and awe.

When it comes to the heart, our best bet is to be both lucky and vigilant. Lucky that ours is a good one and stays that way, and vigilant to avoid the many threats to its ongoing well-being.

Recently, while on a ward round with the physicians at Moto’otua Hospital in Apia, I saw a young woman called Sepa. She was 24 and had not been so lucky. Sepa came from Savai’i, the big island, and had been admitted with severe heart failure and weight loss. Many years ago, as a child, Sepa—like so many others—had an infection caused by a particular bacterium called Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as the group A Streptococcus. The main symptom of these infections is a sore throat. Untreated or inadequately treated with antibiotics—simple penicillin is the antibiotic of choice—this can go on to cause an inflammatory condition that affects the valves of the heart.

Why this happens is the subject of much research. Each advance in knowledge throws up as many questions as answers, but what is clear is that this is a case of friendly fire. The bacterium has a protein in its cell wall that is similar to that on our heart valves. When our complicated and clever immune system kicks in to knock off the bacteria, those cells that are there to help us become confused and also attack the heart valves themselves. This low-grade assault can continue and intensify with further infections and exposure to the bacterium. Ultimately the inflammation that this causes can destroy the valves and ruin our hearts.

Once diagnosed, children who have suffered from a bout of acute rheumatic disease can still do well with regular injections of penicillin to halt or slow the progression of the disease. None of that happened with Sepa—watching her, miserable and uncomfortable on her bed, was heartbreaking and I knew then that she was not long for this world.

Under normal circumstances, the heart is a pump that circulates blood around the body. On the face of it, that might seem like a simple task but in reality it is more complex given the high degree of reliability we expect from this bit of muscle in the middle of our chest. Seventy-five beats a minute for every hour of every day of every year that we live. 4500 heart beats an hour; 108,000 heart beats a day, and over 1.5 million heartbeats a year for all of our lives. That is an awe-inspiring performance, especially considering that we are now living into our mid to late 80s.

The rhythmical comings and goings that make up each beat are also extraordinary. Set to music they are a symphony of coordinated intent that mere words cannot describe … but I will try anyway.

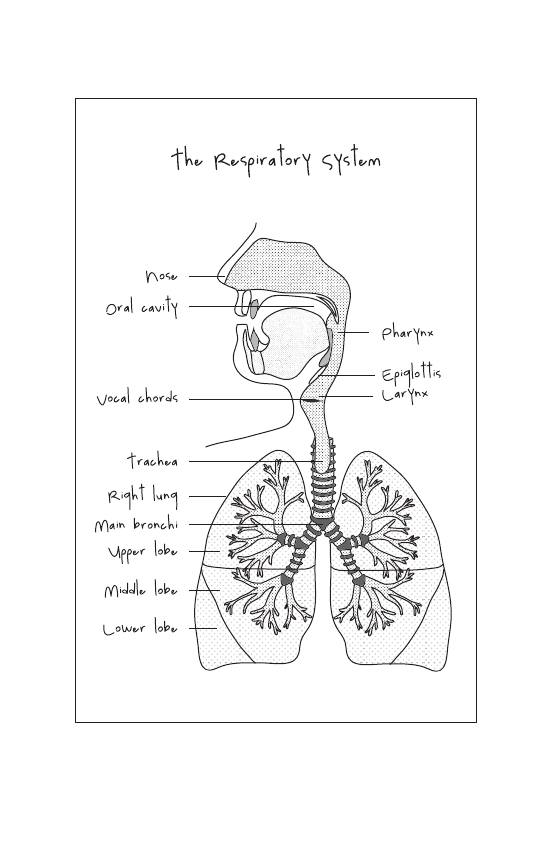

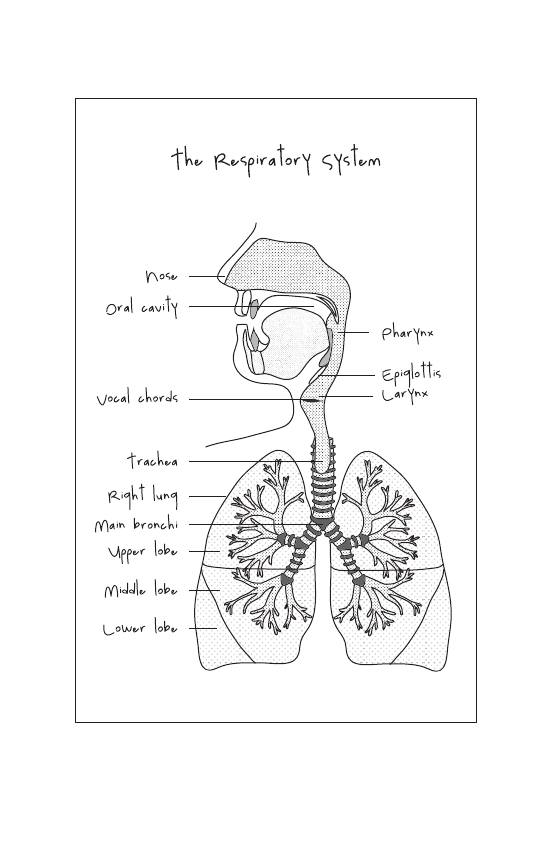

The heart is essentially a pump with two interdependent sides each with two chambers. The right pump and the left pump both work in parallel. Each side has an atrium into which blood first enters before being ejected into the main pumping chamber, the ventricle. Put simply, the right side of the heart circulates blood to and from the lungs, then the left side of the heart sends blood rich with oxygen to the tissues of the body. This flow of blood is so crucial to our well-being and is so cleverly designed it deserves a more detailed explanation: the heart receives ‘blue’ blood from the veins that drain the organs of the body once they have extracted the oxygen they need to continue to function. That venous blood enters the right side of the heart, initially into the right atrium—the upper right-hand chamber. Once there, following the coordinated contraction of the atrial muscles, the tricuspid valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle—the lower right-hand chamber—opens allowing the ventricle to fill. Then the muscles of the right ventricle begin to contract, closing the tricuspid valve behind it and eventually opening the pulmonary valve, ejecting blood forward into the pulmonary arteries. As the pressure in the right ventricle drops, it begins to refill and the pulmonary valve closes. From the pulmonary arteries, this ‘blue’ blood goes to the lungs where it picks up much needed oxygen and gets rid of the waste product carbon dioxide, which is ultimately expired by our lungs—another amazing bit of gear. This, the pulmonary circulation, is a relatively low-pressure affair in contrast with that performed by the left side of the heart.

The now oxygenated blood returns from the lungs to the left side of the heart, entering the left atrium. Once there the muscles of the atrium contract, opening the mitral valve and causing the blood to flow into the main pumping chamber of the heart—the left ventricle. As the muscles of the left ventricle contract, the pressure in the chamber rises to close the mitral valve and open the aortic valve ejecting blood rich with oxygen into the aorta at a high pressure, and from there to the tissues of the body.

As the pressure in the left ventricle falls the aortic valve closes, ensuring blood flows forward under pressure into the aorta and from there into the smaller arteries that carry oxygen to all of our organs and tissues. We call each beat from the left side of our heart our pulse and count its rate by the minute. We feel that in our wrists or arms or neck and sometimes when lying strangely we can hear it in our heads. The pressure that propels the blood is called blood pressure and we measure that with a cuff around the arm. These simple everyday terms barely scratch the surface of the complexity that underpins this marvellous servant that dances its dance with such coordination, reliability and grace. A video image of the heart at work set to music would be a certain Oscar winner.

In rheumatic disease, it is the left side of the heart that is mostly affected. For Sepa, her mitral and aortic valves were so damaged that as much blood was going backwards out of the heart as there was going forward in the direction it was supposed to go. As a result, her lungs were full of fluid and she was short of breath; her abdomen too was fluid filled and her liver congested. Her heart was so badly damaged that the only hope for her was transfer to New Zealand for surgery but by the time she came to us, it was too late even for that. Despite all efforts to help her, Sepa died three days after she was admitted to hospital.

Rheumatic fever is a disease that has largely been eradicated from much of the developed world but persists in populations that have a genetic predisposition to it accompanied by environmental factors like overcrowding and poverty. Māori and Pacific children seem particularly at risk, with an unacceptably high incidence of this disease in Samoa and in areas of New Zealand—like Northland, South Auckland, the East Cape and Porirua—where there is overcrowding, economic deprivation and delayed access to health services.

My father died of ischaemic heart disease, a condition where the arteries that take blood and oxygen to the heart itself become increasingly narrowed. That disease first became evident when he was in his early fifties.

Dad was a good sleeper and, unlike me, had that ability to doze till late in the morning. Also unlike me, he was a private man, not one to share his worries or concerns. His heart problems became evident when he was 55—still a young man—when one morning, he was up uncharacteristically early and not wanting to wake my mother, he took himself to the kitchen, clutching his chest in pain. He was short of breath and he felt cold and clammy. Later he told me that he thought he was going to die. Unwilling to bother anyone he decided to ride it out sipping milk thinking it was a stomach upset. Thankfully my mother found him and called an ambulance.

Thinking this to be heart pain, the paramedics gave him oxygen to breathe, a spray of glyceryl trinitrate under his tongue and a small dose of morphine in the vein. Dad’s pain immediately eased and he was taken to hospital. They were right, those paramedics. Dad’s pain was classic angina pectoris; a shrill and alarming distress call by the cells of the heart when they become starved of oxygen. An electrocardiogram or ECG done at the time confirmed that. My father’s pain was the result of a heart attack, which caused permanent damage to his heart. He spent a few days in hospital recovering then came home with a raft of medications as well as suggestions for an exercise programme, which he duly ignored.

Ischaemic heart disease contributes to the death of thousands of New Zealanders every year. Most at risk are those of us with a family history of the disease, being anyone with relatives who have suffered from the condition. Smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, poor diet, and a lack of exercise make our risk of disease and death even higher.

My father’s reluctance to seek immediate help probably led to the irreversible damage done to his heart. But back then he was also lucky that his heart kept its rhythm because when it doesn’t the consequences can be disastrous and sometimes fatal.

Every second week, for seven years, I commuted between my home in Auckland and work in Wellington. For my sins I was working half time as the Principal Medical Advisor both to the Minister of Health and to the Director General of Health. It was an interesting but exhausting time, and by the end of each week all I could think about was getting home.

One wintry Thursday afternoon, as I lined up to get on the 4 p.m. plane home, I happened to exchange glances with an affluent looking, middle-aged couple ahead of me in the queue. We briefly acknowledged each other in that polite way you do when you make eye contact with strangers. Once on the plane and underway on the hour-long flight, I stretched out as best I could and cast my mind forward to the weekend ahead. Suddenly the senior air steward walked past looking anxious then pulled an oxygen bottle from the locker above my head. ‘Do you need any help?’ I asked.

‘Are you a doctor?’ came her hopeful reply.

I got up and followed her down to row thirteen, to where that very same couple were seated. The well-dressed man in the aisle seat was slumped forward, his breathing noisy and his lips blue. He was unconscious.

I took the oxygen bottle from Sue, the air steward, and immediately put the mask on the man’s face, pulling his jaw forward as I did. He pinked up fast. Even the passenger behind him noticed this, helpfully observing, ‘His colour looks better.’

As I introduced myself to the man’s partner, instinctively I felt for the pulse in his neck and was relieved to find that it was regular and strong. The couple, Maria and Don, were married and off to the States on a business trip. Maria told me that Don was 58 years old, in generally good health, and had no history of heart disease but took medication for high blood pressure. Quite suddenly, as she was telling me this, his pulse disappeared and Don stopped breathing.

In my language, we call this a cardiac arrest. A state where there is no forward flow of blood from the heart and no blood or oxygen being delivered to the tissues of the body. If not treated immediately people just die. If restoration of the person’s circulation is delayed, the lack of oxygen to the tissues will cause varying degrees of damage to the body—especially to the brain.

I looked up at Sue and she looked at me. ‘Cardiac arrest,’ I whispered. She nodded towards the front of the plane.

With help from another passenger, we lifted Don out of his seat then carried and dragged him to the front of the plane, while at the same time ripping off his jacket and opening his shirt. Sue unpacked the on-board medical kit while I began giving him CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) chest compressions at about 100 a minute.

The most likely cause of cardiac arrest in situations like this is a disorder of the heart’s rhythm, called ventricular fibrillation (VF). When that happens all of the individual cardiac muscle fibres contract independently of each other instead of in the coordinated way necessary to eject blood out of the heart and into the tissues of the body. A heart in VF squirms and writhes rather than pumps and it looks as awful as are its consequences.

VF occurs in people with ischaemic heart disease and can be associated with a full-blown heart attack or with more minor bouts of ischaemia. Immediate restoration of the normal cardiac rhythm is possible by delivering an electric shock to the heart using a defibrillator.

‘Is there a defibrillator in there?’ I asked, while continuing the chest compressions. Every 20–30 compressions I briefly stopped to give Don an oxygen breath using an inflatable bag and a mask applied firmly to his face. Each time I did that his chest rose and I was pleased.

To my delight and relief, there was an automatic external defibrillator (AED) on board. It was yellow and called HeartStart—‘Please,’ I thought, ‘yes please!’

These machines are cheap and clever. They are designed to be used by bystanders who have no training in resuscitation and they have saved thousands of lives worldwide. Cool and calm, Sue applied the pads to Don’s chest, one on the chest wall just to the left of the midline below the throat, the other on the left side of the chest. The AED detects the patient’s rhythm, tells you what it is and, if required, will automatically deliver the appropriate electric shock to the chest in the hope that it will restore the patient’s normal heartbeat.

This HeartStart machine also had a small screen that displayed the patient’s rhythm. As soon as we applied the pads it was obvious that the cause of this man’s cardiac arrest was ventricular fibrillation. Crossing the screen was the telltale pattern of VF, an uneven, chaotic pattern of up and down lines. Before I could say, ‘All clear!’ and activate the electric shock, the machine announced in an American accent, ‘Shockable rhythm. Shockable rhythm. All clear. All clear.’

Then boomph! 200 joules of energy shot down the wires into the pads and via them through the patient’s chest and across his squirming heart.

Lo and behold, after a very brief pause, across that little screen a more orderly picture emerged—something we call normal sinus rhythm. In his neck where there was once a pulse and then there wasn’t, I could feel a pulse again. Slow at first and a bit weak because he was quite blue. However, with more regular oxygen breaths, Don became increasingly pink and his heart rate went from 30 beats a minute to 60 to 90 to 110. Although still deeply unconscious, I felt his own respirations begin to kick in again.

It was only then that I looked up for the first time. I was jammed into the window of the first row of the plane. The man’s legs stretched across the aisle into the area where patients board. It seemed that the world had stopped because there was complete silence on board. You could have heard a pin drop and around me I saw the saucer-like eyes of other passengers staring at me.

Opposite me was the deputy prime minister, who I’d clashed with over health policy some years earlier, and I thought, ‘Bugger you! Not bad for a “mere public servant”, eh?’ He looked away with no sign of acknowledgement, not even a smile or a wink.

Although it felt like an age, this had all taken less than five minutes. I put a drip in Don’s arm and as we got closer to Auckland he began to rouse in an irritable and unhelpful way—a good sign I thought but potentially not so helpful right then so I gave him a small dose of sedation to keep him calm until we reached Auckland.

Once we landed, the passengers disembarked from the rear door and the paramedics came on board. We intubated Don, placing a breathing tube in his windpipe to take control of his breathing and to make him more secure for his ambulance ride to my second home, Middlemore Hospital.

He did well, that man. After a couple of days sedated and on a ventilator doing what we could to maximise the chances of a good neurological recovery, we stopped the drugs keeping him asleep—Propofol, and Fentanyl, a short-acting narcotic—so we could see what he was like.

He woke up pretty well. When we told him what had happened, he smiled a smile that I will never forget—big and wide, as if he knew instinctively how close he had come. He was momentarily dead, then alive again. What a weird stroke of luck. He recovered fully and resumed his life.

His wife bought me a shirt as a gift—it’s gorgeous and every time I wear it I think of her and of him. It turns out I know his GP so I still get the occasional update on how he’s doing—he’s still working but now divorced! I was sad to hear that but I suppose it’s hard to think you can be the same person after living through something like that.

He really was lucky because the outcome for patients who suffer an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is always uncertain. For those whose collapse is due to VF, immediate defibrillation will deliver the best likelihood of a full recovery. Many who collapse and receive immediate and effective bystander CPR, followed by defibrillation and a quick restoration of their own cardiac rhythm, may also do well. However, the longer the delay between collapse and restoration of the heart’s natural rhythm, the worse the person’s outcome.

Don’s life was saved by the immediate availability of a cheap, easy-to-use AED. In some parts of the world—Seattle is perhaps the best example—AEDs are everywhere and their locations are widely known. In the event of a collapse, emergency services will even direct bystanders to the nearest one. Do you know where your nearest one is? It would be a good idea to find out. If there isn’t one near you, maybe you or your employer should buy one and ensure the people in your building know where it is kept. It might be that one day you or one of your mates might wake up with a smile on your face having joined the growing numbers of people who were gone but came back.

When poor outcomes result, they are due to damage to the brain—the one organ in the body whose tissues will not tolerate a cessation in oxygen delivery for more than a few minutes. Sadly, the parts of the brain that are most likely to be damaged first are the ones that make us uniquely who we are, those parts of the brain that have evolved most recently and set us apart from other forms of life, giving us the ability to socialise, remember, recognise, love and contribute.

Unlike my father, who had every reason to have a cardiac arrest, this appalling event can be visited on the young and seemingly well. Tiara was just such a person—a bright 20-year-old studying commerce at a university a long way from home.

Like many of her friends, she worked hard but she was social too. One Friday evening she was out with friends, bar hopping and dancing till the early morning. Although the story will always be a little vague, it seems that Tiara got home just after 2 a.m. and went straight to bed. About an hour later her flatmates heard a noise from her bedroom and went in to investigate. From what they later described, it seemed like Tiara was having a convulsion; she was thrashing about the bed unresponsive and frothing at the mouth. They called an ambulance and waited.

By the time help arrived Tiara had stopped breathing and she was blue. The two paramedics were young and efficient. It was immediately clear to them that Tiara didn’t have a pulse so one of them began CPR. The other attached the defibrillator leads, which showed the flat line of asystole—no electrical rhythm at all—and then slipped a breathing tube into her windpipe to give her some oxygen. In between breaths, she also put an intravenous line (IV) into a vein in her arm and gave Tiara an immediate 2 milligram injection of adrenaline to help kick start her heart. All the while her colleague continued the chest compressions at about 100 per minute. This sequence of events I know so well—chest compressions, oxygen breaths and intravenous adrenaline was repeated many times over the next twenty minutes.

Then quite suddenly Tiara’s heart kicked back into action, all over the place at first but soon resuming its regularity like nothing had happened. She had a pulse and soon pinked up nicely, but she remained deeply unconscious on her way to hospital.

For some, like Tiara, who suffer a prolonged cardiac arrest, if we persist with resuscitation, the heart will often kick back into action oblivious of damage already done elsewhere. For healthcare providers, once a patient is resuscitated—no matter how long they may have been ‘down’—it becomes a waiting game during which any obvious cause of the arrest is treated and damage control measures are put in place to give the brain the best chance of recovery.

Although the events surrounding a collapse and arrest might not seem to bode well for a good recovery—in this case, a prolonged down time and no bystander CPR before the return of a spontaneous circulation—we have no technology or tools to accurately assess what the true outcome will be other than by waiting and seeing. That wait will usually be several days while the patient is kept in an induced coma. At the right time, often at 72 hours postarrest, any drugs keeping them asleep are stopped and the patient is assessed. For distraught families desperate for a good outcome, this is a dreadful time full of fear, hope and prayers.

Tiara’s cardiac arrest may well have been the result of a prolonged seizure and the lack of oxygen that can so often accompany that. Why she had the seizure we may never find out—she had never had any before and the tests that were done to identify potential causes, including a comprehensive toxicology screen looking for evidence of drug ingestion, proved negative.

The heart, our reliable servant in so many ways, is a resilient organ and can put up with a lack of oxygen much better than other tissues of the body, especially the brain. The one organ in the body that so defines us as who we are, the brain might tolerate a lack of oxygen for two to three minutes but if that persists for much longer, some damage and lasting effects will result. On the face of it then, Tiara’s story was worrying. There had been a five-minute delay before the paramedics arrived and another twenty minutes of CPR before her own heart finally started.

The initial finding of asystole, the flat line on the monitor, was also a worry. If our theory was correct—that the cardiac arrest was the result of a prolonged seizure and with it a long period where her breathing was so badly affected her tissues were starved of oxygen—her brain would certainly have suffered significant damage well before her heart had stopped.

This proved to be the case. Once in hospital, Tiara was managed in the intensive care unit (ICU). She was kept sedated with Propofol and on a ventilator for the first few days, while medical staff concentrated on providing the treatments and care that would create the best chances for Tiara’s brain to recover. Her temperature was controlled to keep her at 36.5 degrees Celsius; the head of her bed was elevated to 30 degrees; her blood pressure, the CO2 and sodium levels in her blood were managed to minimise any swelling of her brain. Those treatments persisted for 72 hours, apart from short periods twice a day when the sedation was stopped to allow Tiara to ‘wake up’ so she could be assessed.

Propofol, the drug we give by intravenous infusion to keep intensive care patients either sedated or anaesthetised depending on the circumstances and dose, is a medication I now refer to as the ‘Michael Jackson drug’. It is white and looks like milk. Sadly for Michael Jackson, in his case it was inappropriately prescribed, almost certainly not monitored, and seemingly implicated in his death. In our hands, Propofol is safe and extremely useful as a sedative agent. Its effect is short lived so once stopped, our patients will emerge ‘clean’ and not befuddled by other medicines enabling us to make an accurate clinical assessment of their level of consciousness.

That bedside assessment is beguilingly simple. It does not involve expensive technology or tests. It is based on clinical observation and the responses we get to simple stimuli. The best result we might expect to see from a patient emerging from sedation following a cardiac arrest is that they wake normally, open their eyes and respond appropriately to commands showing an understanding of what is asked of them: open your eyes, squeeze my hand, poke out your tongue are the kinds of things we commonly start with.

The worst result is when people don’t wake at all, remaining deeply unconscious with their eyes closed and showing no response to voice or a painful physical stimulus. In between those two poles there exists a range of responses that have been correlated with outcome. Those responses form the basis of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), first described by two Glaswegian neurosurgeons, Graham Teasdale and Bryan Jennett, to describe levels of consciousness associated with a traumatic brain injury. Their scale—from a normal score of 15 to the worst score of 3—is now part of everyday medicine and used to assess level of consciousness no matter the cause.

Twenty-four hours after her admission to the intensive care unit, ventilated and sedated still, Tiara looked good. Walking into her bed space there was a sense of calm and all was tidy. Her pupils were briskly reactive when I shined the bright light of a small torch into them. From the monitor above her head came the reassuring regular bleep associated with a steady pulse, and on its screen was displayed a normal heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation. By this stage too, all Tiara’s blood results had returned to their normal ranges. A clean sheet covered her from the neck down and her hair had been washed and neatly brushed. If it wasn’t for the breathing tube in her mouth you might have thought she was just a pretty young woman having a sleep.

Her nurse, always at the bedside, stopped the Propofol infusion, which was running at 10 millilitres an hour, and we waited. Although Propofol wears off in a couple of minutes, it sometimes takes a little longer for a patient’s underlying state to emerge. This first time, despite waiting for over half an hour, Tiara showed no spontaneous sign of wakefulness. The only change was that she had started to take some breaths for herself. Her eyes remained closed and she showed no response to the pain of me pressing down on her eyebrow, then applying pressure to the nail beds of her fingers and toes. She had the lowest recordable GCS, a score of 3, a real concern but perhaps not unexpected.

Tiara was the eldest of seven children. Her mother had died three years before and the rest of her siblings lived on the family farm with their dad and two aunties. By this stage, all the family had arrived at the hospital and were with me when we stopped the Propofol. We had already spoken, initially by phone then more formally several times as various family members arrived at the hospital. Despite those conversations and my obvious anxiety about how this would work out, they were a devout family and remained more optimistic than I was about a good outcome for Tiara.

Over the next few days we repeated the exercise of stopping the Propofol and allowing Tiara to wake. Each time there were some changes but none of them particularly hopeful for a good recovery. Her breathing would quicken and deepen and she would sweat. After a few days, her eyes would open to a painful stimulus, her pupils would rove from one side to the next and she would roll her shoulders inward then straighten and stiffen her arms and legs. I recognised these as signs of severe neurological damage, but her younger sister April thought Tiara recognised her and responded to her voice. I could see no sign of that—to me it was time to accelerate the difficult but essential conversation with the family about next steps.

I explained that, in time, it might become apparent that despite our best efforts not only would Tiara not improve, she would most likely deteriorate. Should that occur, our ongoing active support would hold no hope of bringing her back. If that were to happen, I asked whether they would agree with our plan to recognise the limitations of what we could achieve ourselves and turn our attention to Tiara’s comfort. Our goal then was to return her to a more natural state or as I so often say to families, put her in the hands of G-d.

I spoke about the dishonesty of pretending to be able to do things we simply cannot do, and the indignity of prolonging suffering and hope when there is no hope to be had from our interventions. Allowing a family to believe that we can cure and fix things we clearly cannot is a lie. It does a great disservice to all of us and to the credibility of medicine as a whole. This was the nature of our discussions over the next ten days.

By this stage Tiara was breathing for herself and off the ventilator. She was being fed through a nasogastric tube that was passed through her nose, ran down the back of her throat, down her oesophagus and into her stomach. During this time, the family and I reached an agreement that we would not escalate care by putting her back on the ventilator should she deteriorate.

Although mostly deeply unconscious and not doing much, those episodes of ‘physiological distress’ became increasingly frequent. Perhaps triggered by hearing sounds or being stimulated by a touch, her breathing would again quicken and her pulse race; she would sweat profusely and her limbs would roll and stiffen. This was truly awful. There was no coming back from this—of that I was certain.

As those abnormal movements intensified, my conversation with the family turned again to her level of consciousness and whether she was aware of the distress so evident to us. At the same time, more and more of the family could see what I could see but a small group held on to the belief that she would improve, that G-d would save her with a miracle or that there would be a test or a procedure that would eventually make her better. Staunchest of those was her younger sister April, a university student like Tiara. She loved her sister dearly, and it was this love and her sense of devotion and duty to her to ‘not give in’ that was the barrier to her accepting the truth that nothing would restore Tiara to the happy, smart, fun-loving sister and best friend that she once was. Maybe I was a bit slow understanding this but once I did our conversation reached a new and much more meaningful level while reassuring and acknowledging April’s love and devotion to her sister.

Soon we agreed a new goal for Tiara, not the impossible—pretending to be able to restore her to her former self—but to make our main priority the maintenance of her comfort and her dignity.

And so we began a low-dose infusion of medicines to make true what we had all agreed—a cocktail of morphine, haloperidol and hyoscine continuously and slowly delivered just under the skin on Tiara’s belly. Within an hour a quiet peace settled over her and in the room. Overnight that sense of calm allowed the emergence of a new set of conversations about Tiara, about her childhood and the funny and silly things that were so much a part of her growing up. April, her devoted sister, laughed and cried. The eleven-year-old twins, once frightened and terrified, seemed to relax, looking on wide-eyed at the events that were unfolding around them. Their dad John, never the same person after the death of his wife, smiled too. Several days later, peacefully, quietly, free at last, Tiara drifted off.

The following day I met with the family for the final time. They too were at peace. Tiara’s aunt Tia pulled me aside to thank me and to tell me—with a sense of relief and acceptance—that Tiara had passed on the ninth and final day of the novena. I smiled, having no idea of what she meant.

My father’s death still lives with me, although with the passing of time I have forgiven myself for many of the things that for so long I beat myself up about.

How could I have not gone down to Wellington earlier? Perhaps I could have done more to help him? What could I have done? Suggested he go back into hospital?

Dad hated hospitals. During his last ever admission for chest pain ten years before he died, he became delirious and had terrible nightmares. He was aware of what was happening and felt deeply hurt and insulted by the way the staff had treated him. He signed himself out and never went back. In fact, he went directly to see the family lawyer, the expensive one whose signature ran across the entire width of an A4 page, to sign an advance directive stating that he would never go back to Wellington Hospital no matter the circumstances. My father was a hot-headed man at times.

If I had been there, could I have helped him at home? Was it fair that he died alone with my mother?

I know that if I had been there my mother would have wanted me to resuscitate him and I know that Dad would never have wanted that. If I was there and didn’t try or tried and failed, I am not sure that in her heart, my mother would ever have been able to forgive me.

If I had been there at least I could have told Dad one last time how much I loved and admired him.

He knew that but this and many more things still play on my mind today.

‘The end matters,’ wrote Atul Gawande in his book Being Mortal, ‘the end matters because that’s what we remember and that’s what we carry with us as we grow up and as we grow old.’