1

Beginning Already

‘HERE. … I SAY. … Yes. … That’s me. …’

Roger swallowed a bit of chocolate unsucked and unbitten. He and Titty leaned together from the doorway of the railway carriage. The train had stopped at the junction. There were ten miles more to go along the little branch line that led into the hills. Somewhere down the platform milk-cans were being shifted, making a loud clanging noise, so that, at first, they had not heard what the porter was calling out as he walked along the train, looking into one carriage after another. Now they heard it plainly.

‘Mr Walker. … Mr Roger Walker. … Mr Walkerrr. …’ The porter was going from door to door all down the train.

Roger jumped from the carriage while the porter was still two doors away.

‘It’s me,’ he said. ‘I’m Roger Walker.’

The porter looked at him.

‘You, is it?’ he said. ‘Come along with me then. We’ve no time to lose, but they’ll be a minute or two yet with them cans. Eh? Eh? … It’s a basket for you. There was two, but one was for folk that come by the earlier train. We’ve to let fly before your train goes on. This way. We mun look sharp now. I’ve left it ready at end o’ t’platform.’

Titty was just getting out when a farmer’s wife blocked the way making ready to get in.

‘Here, my dear, you take a hold of this bag,’ she said.

Titty took it and put it on the seat. The farmer’s wife handed up one parcel after another and then climbed up herself.

‘Losh! the heat,’ she said, mopping her face and counting her parcels. ‘This weather’s enough to maze a body’s brains. … Three … five … and two’s. … Nay, that’s nobbut six. …’

Titty, what with the farmer’s wife and the clatter of the milk-cans, had not heard what the porter had said, but she saw him hurrying off and Roger running beside him. She looked at their own small suitcases and hesitated.

‘Nay, nobody’ll touch them,’ said the farmer’s wife.

‘Thank you very much,’ said Titty, jumped down, and ran after Roger and the porter.

‘But what is it?’ Roger was asking, cantering sideways and just dodging a milk-can that was in the way.

‘Pigeon,’ said the porter. ‘Here you are now. Take this pencil. You’ve the book to sign.’

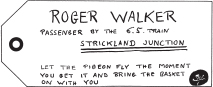

Roger, taking the pencil, signed his name in the place the porter showed him. Titty was already looking at the basket, a brown, varnished, wicker basket, lying on the platform. She read the label:

In a corner of the label, looking almost as if it were an official seal, was a small skull and crossbones done in blue pencil.

‘It’s Nancy,’ cried Titty. ‘She’s beginning something already.’

‘There’s a live pigeon inside,’ said Roger. ‘Listen to it.’

‘You’ve not got much time,’ said the porter. ‘Cut the string there, and pull out the peg. All these small pigeon-baskets open the same way. Wait a minute. Best bring it beyond the roofing, so it gets a fair start in t’open.’

‘Let it go?’ said Titty. ‘We’ll never catch it again.’

The porter laughed.

‘They’ve been sending one for me to fly for them every other day this last week. Name of Blackett, the folk sending ’em.’

‘We’re going to stay with them,’ said Titty.

‘Pigeon’ll be there long before what you will.’

Roger had cut the string and pulled out the peg.

‘I can see its eye,’ he said.

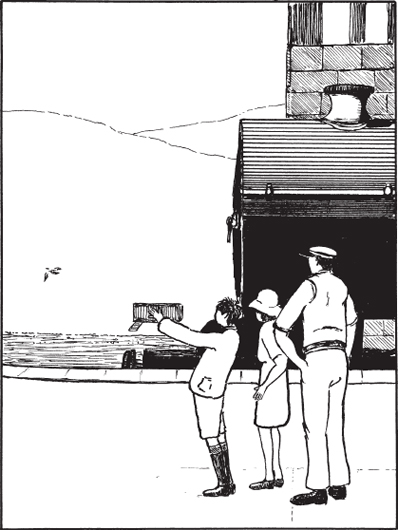

They had walked nearly to the end of the platform, beyond the end of the station roof and were standing in the open air beside the engine.

‘Let the door fall,’ said the porter. ‘Hold up the basket. … There she goes. …’

The wicker door fell open. The shining bronze and grey head of the pigeon showed for a moment. Pink claws gripped the edge of the door. The basket was suddenly lighter, and Roger felt as if he himself had tossed the pigeon up into the air. It flew up above the roof, above the drifting white steam from the engine, and swung round in circles above the house tops, above the cricket ground, while the porter and Titty and Roger watched it. The engine-driver and the fireman leaned out from the footboard to see it too. Suddenly, when it was already no more than a circling grey speck, hard to see in the dazzling summer sky, the pigeon seemed to make up its mind and was off, north-west, straight into the sun, towards the blue hills of the lake country.

‘I can still see it,’ said Titty.

‘I can’t,’ said Roger. ‘Oh yes I can. … No. It’s gone.’

‘You’d better hurry back,’ said the porter, and he nodded to the engine-driver, who nodded in return, as much as to promise not to start until they were in the train. The guard’s whistle blew just as they reached the carriage.

‘Look here,’ said Roger to Titty as secretly as he could. ‘Oughtn’t we to give the porter something?’

Titty was already digging in her purse.

‘That’s all right,’ said the porter. ‘You keep it for pigeon food.’

‘But it’s not our pigeon,’ said Titty.

‘No matter,’ said the porter, closed the door on them, and waved a friendly hand as the train pulled out.

‘Thank you very much,’ they shouted at him from the window.

‘What was all to do?’ said the farmer’s wife, who had now counted all her parcels and was sitting in a corner of the carriage with her hands folded on her lap. ‘Pigeon to loose? Now my son down in t’south, he’s a great one for pigeons. Starts flying ’em when they’re nobbut squeakers, he calls ’em. He flies ’em further and further, and before summer’s out he’s sending ’em up here to Dad and me, and we loose ’em for him in t’morning and they’ve flown all t’length of England before dark.’

‘Do you send messages by them?’ asked Titty.

‘Love from home,’ said the farmer’s wife. ‘Aye. Dad’s put that on a scrap of paper and tied it in the ring on a pigeon’s leg before now.’

‘I say,’ said Roger. ‘That’s what Peggy meant when she wrote in her letter that they’d got something better than semaphore messages for this year.’

‘Isn’t it a good thing we were able to come?’ said Titty. ‘We might have had to wait at school.’

Roger leaned out of the window, with his eyes screwed up against the wind.

‘I can’t see a sign of that pigeon,’ he said.

‘It went off at such a lick,’ said Titty. ‘The train’ll never catch it up.’

‘Far to fly?’ asked the farmer’s wife.

‘It’s a house called Beckfoot at the other side of the lake.’

‘Mrs Blackett’s?’

‘Do you know her?’

‘Aye, and her daughters too, and her brother Mr Turner that’s for ever gallivanting off to foreign parts. …’

‘We know him too,’ said Roger. ‘We call him …’ And he stopped short. There was no point in giving away Captain Flint’s name to natives.

‘You’ve been here before, likely,’ said the farmer’s wife.

‘Oh yes,’ said Titty. ‘We always stay at Holly Howe … at least Mother does … but Mrs Jackson’s got visitors for the next two weeks. … Mrs Blackett’s having us till then because Mother didn’t want Bridget to give us all whooping-cough.’

‘We’ve come straight from school,’ said Roger.

‘Eh,’ said the farmer’s wife. ‘I know all about you. You’ll be the young folk that were camping on the island down the lake two years since when Mr Turner had his houseboat broke into. And you were here again last winter when the lake was froze over. But I thought there was four of you. …’

‘Five, with Bridget,’ said Titty. ‘John and Susan must be here already. It isn’t so far from their schools.’

‘And weren’t you friends with the two at Mrs Dixon’s?’

‘Dick and Dorothea Callum,’ said Titty. ‘They won’t be here for ages yet, because their father has to correct examination papers.’

It had been a long day’s journey from the south, but the last few minutes of it were going like seconds. Already they were in the hill country where walls of loose stones divided field from field. Grey rocks showed through the withered grass. Grey and purple fells lifted to the skies. Titty and Roger hurried from side to side of the carriage, looking first out of one window and then out of another.

‘Fair parched everything is,’ said the farmer’s wife. ‘No rain for weeks and none coming, and no water in the becks. Folks are at their wits’ ends in some parts to keep their beasts alive.’

‘Hullo!’ said Roger. ‘There’s been a fire.’

‘More’n one,’ said the farmer’s wife.

The train was running through a cutting, the sides of which were black and burnt.

‘Sparks from the engine?’ said Roger.

‘Aye,’ said the farmer’s wife. ‘And where there’s no engines there’s visitors with motor cars and matches and cigarettes and no more thought in their heads than a cheese has. It takes nobbut a spark to start a fire when all’s bone dry for the kindling. Eh, and here we are. Yon’s my farm. …’

A farmhouse, not unlike Holly Howe, flashed into sight and was gone. The farmer’s wife jumped up and began collecting her parcels. The train came suddenly round a bend and began to slow up.

LETTING FLY

‘There’s the lake!’ Titty and Roger cried together.

Far below them, beyond the smoking chimneys of a village, glittering water stretched between the hills. The train was stopping for the last time.

‘The platform’s on the other side,’ said Roger.

‘Who’ll be there?’ said Titty.

‘Nobody,’ said Roger.

But a red knitted cap was bobbing up and down among the people waiting on the platform. In another moment Nancy Blackett was at the door, and they were saying goodbye to the farmer’s wife and struggling down with their suitcases.

‘Here you are,’ said Nancy. ‘Hullo, Mrs Newby. Well, Roger, did you get the pigeon all right? Did you let it fly? Mother and I had to start before it got home. She’ll be here in a minute. Shopping. Gosh, I was nearly too late to meet you. You didn’t forget the basket. Good. Good. Shiver my timbers but I’m jolly glad to see you. Come on. Let’s get your boxes out of the van, and then we’ve got to go to the Parcels Office.’

Everybody in the world seemed to be talking at once all round them, but presently their boxes came out of the van among the others, and Nancy, telling the porter to keep a look-out for Mrs Blackett, was hurrying them along the platform.

‘Is Captain Flint in the houseboat?’ asked Roger.

‘He’s still in South America, isn’t he?’ said Titty.

‘He ought to be here, but he isn’t,’ said Nancy. ‘His mine wasn’t any good and it serves him right, not being here in time for the beginning of the holidays. But he’s on his way home. Some of his things have come already, but not the most important. At least it hadn’t yesterday. It may be here today.’

She took them into the Parcels Office.

‘You haven’t a crate or a cage with something alive in it?’ she asked the man behind the counter.

‘Rabbits?’ asked the man.

‘The trouble is we don’t exactly know.’

‘Miss Blackett, isn’t it?’ said the man, running his finger down the columns of his book. ‘No, Miss, there’s nothing come for you. Not yet. Unless it’s come by this train.’

‘I’ve looked in the van already,’ said Nancy. ‘Look here, we’ll be awfully busy tomorrow. So I won’t be able to come across. But could you telephone if it comes?’

‘Aye, Miss Blackett, I can do that.’

‘But what is it?’ asked Roger.

‘It’s called Timothy, anyway,’ said Nancy.

‘Another monkey?’ said Roger.

‘Or a parrot?’ said Titty. ‘He said he might be getting another.’

‘Can’t be either,’ said Nancy, as they went back to the luggage. ‘He said in the telegram that we could let it loose in his room. It can’t be a monkey or a parrot. It must be something that can’t do much damage and doesn’t climb. Dick …’ Nancy checked herself and went on. ‘We’ve been looking through the natural history books, and we’re pretty sure it must be an armadillo. But we don’t know. And we can’t find out, because Uncle Jim is on his way home and we don’t even know the name of his ship. Whatever it is, he must have sent it on in advance, or he wouldn’t have telegraphed. … Hullo, here’s Mother.’

A smallish, ancient motor car with badly dinted mudguards had driven into the station yard. Mrs Blackett, round, small, no taller than Nancy, was talking to the porter. She turned as they came up.

‘Here you are,’ she said. ‘The last of the gang.’

‘Except Timothy,’ said Nancy. ‘He’s not here yet, but they’re going to telephone the moment he arrives.’

‘Yes, those two. …’ Mrs Blackett was looking at their boxes. ‘We’ll have them both on the back. You’ve nothing else, have you, besides those suitcases? And how’s your mother? And Bridget? Oh, I was forgetting you’ve come straight from school, too, and won’t know any more than John or Susan.’

‘We had a letter yesterday,’ said Titty. ‘Bridgie’s only whooping about twice a day. So she’s all right, and so’s Mother. At least she didn’t say she wasn’t.’

‘Hop in,’ said Mrs Blackett, when the boxes were strapped on the luggage grid. ‘Thank you, Robert. You come in front with me, Titty. Don’t anybody sit on my parcels. There are eggs in that basket, and tomatoes in the paper bag. Slam that door, Roger. Give it a push from inside to see it’s properly shut. That’s right, Nancy. … I’m glad your uncle didn’t hear me get into those gears. … Yes, I’ve remembered to take the brake off. …’

There was a fearful crash and rattle, and the little old car swung out of the station gates and turned sharp to the left.

‘Don’t we have to go round the head of the lake?’ said Roger.

‘You don’t,’ said Nancy. ‘Not if young Sophocles flew straight.’

Titty, sitting in front by Mrs Blackett, looked round. ‘Why did you call the pigeon Sophocles?’ she asked.

‘You may well wonder,’ said Mrs Blackett.

‘Oh, Mother, do look out for your steering,’ said Nancy. ‘You see, Uncle Jim gave us one, and called him Homer because he was a homing pigeon. And then when we got two more for company, we looked up Greek poets and found Sophocles and Sappho. And there you are. Phew! Mother. Lucky I caught the eggs. …’

Their adventures had very nearly ended before they had properly begun.

‘People ought not to go so fast,’ said Mrs Blackett. She had braked the car so suddenly that Roger and Nancy had shot off the back seat and Titty had nearly bumped her nose on the wind-screen. ‘The roads are crowded with dangerous drivers. … It’s hardly safe to be on them at all. All very well, Nancy. You can laugh as much as you like. People are most careless. Now then, I ought to have sounded my horn, if only I hadn’t been listening to you. …’

‘Did you see who it was?’ said Nancy. ‘It was Colonel Jolys. He took off his hat. … No, don’t try to turn round. He knows you didn’t see him, and I gave him a grin anyway.’

‘What’s he got a trumpet for?’ asked Roger.

‘It’s a hunting-horn,’ said Titty.

‘It isn’t,’ said Nancy. ‘It’s one of the old coach horns. He’s been having a review of his fire-fighters. Didn’t you see those brooms on long handles sticking up out of the back of his car?’

‘It’s the drought,’ Mrs Blackett explained. ‘We’ve had no rain for weeks, and if the fells should catch fire it would be a dreadful thing for everybody, and old Colonel Jolys has been organising so that the moment there’s a fire all the young men know where to go to be rushed off in motor cars to help to beat it out.’

‘They sound coach horns,’ said Nancy, ‘and then see how soon they can start. Everybody who’s got a motor car is in it, and all the men … Oh do look out, Mother.’

Mrs Blackett, who had somehow got to the wrong side of the road, swerved back and straightened again. They were coming down the last steep drop into the little village that the Walkers and Blacketts called Rio. They turned the corner at the bottom. There was the sparkling water of the bay, with its landing stages and its anchored yachts. Roger and Titty had seen it last in winter, frozen and covered with skaters. Mrs Blackett, with a screech of the brakes, pulled up. Nancy was out as the car stopped.

‘Come on, you two,’ she said, and Titty and Roger got out and followed her, wondering, along a wooden boat pier that seemed strangely high out of the water.

‘What’s happened to the lake?’ said Roger. ‘It used to be nearly up to the road.’

‘No rain,’ said Nancy, looking eagerly out beyond the islands. ‘Half a minute. Yes, it’s all right. Sophocles has got home. You stick here and wait for them. …’

Already she was running back along the pier.

‘I say,’ cried Roger, staring after her. ‘Mrs Blackett’s turned round. Nancy’s getting in. They’re off. Hi! I say Titty! They’ve taken all our luggage!’

But Titty hardly heard him. Far away over the water, glittering in the evening sun, she had seen the white speck that had sent Nancy hurrying to the car. Two years had slipped back in a moment, and once again she was seeing for the first time the little white sail of the Amazon pirates.

Roger shook her by the arm.

‘Titty,’ he said, ‘they’ve gone. …’

Titty pointed to the little boat.

‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘John and Susan and Peggy must be coming to fetch us across.’