THE PIGEON-LOFT

4

Mrs Blackett Makes Conditions

IT WAS NO good trying to talk to Mrs Blackett until the paperers and plasterers had gone for the day. By that time the pigeons had been fed and Susan and Peggy had got the camp fire going in the open space in the wood just off the lawn. Mrs Blackett was coming to join them at a meal, tea and supper combined, and the cooks were going to show how good a meal they could make with minced pemmican served hot with plenty of green peas out of a tin and potatoes they had dug for themselves in the kitchen garden. Meanwhile, Nancy and John were at work in the stable yard mending an old handcart. It was a good enough handcart except that one of its wheels kept coming off and one of its handles had been broken. By taking off the good wheel, at Dick’s suggestion, they had found out what was wrong with the other, and the handcart was ready for use and was being run fast up and down the cobbled yard, to make sure that it would not come to pieces again, when Mrs Blackett, hearing the noise, came out to see what was happening.

‘We’ve got to start trekking tomorrow,’ said Nancy firmly. ‘We’ve got to shift the whole camp up to High Topps.’

‘But Ruth, I mean Nancy, you wild creature, whatever for? I thought it was all settled that you were to camp here and go prospecting for gold. Didn’t you find Slater Bob?’

‘Yes,’ said Nancy. ‘And the gold isn’t here at all. It’s up on High Topps. And there’s someone else looking for it. We haven’t got a minute to lose. It’s too late to move tonight, but we’ll get going first thing in the morning.’

‘No,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Impossible altogether. Mrs Walker might not mind so very much, but there are the Callums.’

‘What about Susan?’ said Nancy. ‘She’ll look after them. Don’t go and say “No” right away. Come along and see the others. Hi! John, do go and tell Susan Mother’s coming and everything’s going to be all right.’

‘I never said so,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Don’t tell her anything of the sort.’

But John was gone. This was something between Nancy and her mother. He couldn’t very well join in and say he wanted to get away from Mrs Blackett’s garden. He slipped away through the house, putting his head in at Captain Flint’s study door on the way. Dick was there, reading about gold in the Encyclopaedia. Dorothea was seated at the table taking the chance of scribbling down a few sentences in her story, The Outlaw of the Broads, that she had not had time to finish at school. Titty was looking at the picture of the armadillo.

‘Come on,’ said John. ‘Come along to the camp. Nancy’s begun persuading Mrs Blackett and they’ll be there in two ticks.’

Mrs Blackett seemed to need a good deal of persuading. From the camp on the lawn, anxious watchers saw that neither Nancy nor her mother was in a hurry to join them. The two of them came round the corner of the house into the garden but they did not at once cross the lawn to the group of small white tents. Instead they walked up and down under those curtainless windows. Fragments of talk, sentences, half sentences, single words, floated across the garden. Mrs Blackett was explaining again and again why it was that, though she did not mind having six children not her own safely camped in her garden, she did not at all like the idea of letting them go camping miles away up on the fells where anything might happen to them and she would not be there to help. And then, whenever she got a chance, there came a loud, cheerful rush of persuasive talk from Nancy.

‘As safe as houses. … Much safer in case of earthquakes and things. And anyway, now we know it’s there, it wouldn’t be much fun looking anywhere else. And you know we couldn’t get home every evening. Not from High Topps. Cruelty to animals. We’d be on the road all day and never have any time there at all. Besides, it’d be much better if none of us were here while you’re finishing up the papering and painting. Better for Cook, I mean. And you know you’re always saying Susan can be trusted to be sensible. …’

That was all Nancy, but when she paused for breath, Mrs Blackett began again. ‘It would be all very well if you were all Susans. There’s only one Susan in the eight of you. It’s the Dicks and Dots and Rogers I’d be worrying about. …’

‘Me?’ whispered Roger indignantly.

‘Shut up,’ said Titty. ‘They’re coming.’

Mrs Blackett had turned suddenly off the path and was walking across the lawn to the tents. Nancy, with dancing eyes, as if she knew the victory was won, was close behind her.

‘Where is Susan?’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Oh, there you are.’ She turned aside towards the camp fire, from which Susan had just lifted a boiling kettle.

‘It’s no good trying to get any sense out of my harumscarums,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Tell me, Susan, do you really want to go camping away up on High Topps instead of staying here?’

‘Of course she does,’ said Nancy.

‘Pirates hold their peace,’ said Mrs Blackett, ‘long enough to let Susan answer for herself.’

‘It’s very nice here, of course,’ said Susan.

Mrs Blackett laughed. ‘So you do want to go?’ she said.

‘Only because of the gold,’ said Susan.

‘I’m sure there’s just as much gold here as anywhere else,’ said Mrs Blackett.

‘Slater Bob said High Topps,’ said Susan, ‘and he told us just what to look for. …’

‘Well done, Susan,’ said Nancy.

‘But, of course, there may be other places.’

Nancy almost groaned.

‘If only my brother were at home,’ said Mrs Blackett.

‘But the whole point of everything is to find the gold before he comes back,’ said Nancy.

‘It’s to be a surprise for him,’ said Dorothea.

‘Or if you could only wait till your mothers are here to decide for themselves.’

‘He’ll be here before that,’ said Nancy.

‘And when they come we’ll all be sailing,’ said John.

‘And somebody else is looking for it already,’ said Titty.

‘Not really,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Now, Susan. You tell me, what would your mother say?’

‘She’d say all right if Roger went to bed at the proper time.’

‘She’d tell us about gold-mining in Australia,’ said Titty. ‘She might even want to come too.’

‘I dare say she would,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘But that’s just what I can’t do with the house all upside down. And what about you?’ she added, turning to Dick and Dorothea. ‘What would Mrs Callum say?’

‘She wouldn’t mind if we promised to do what Susan told us,’ said Dorothea.

‘You see how it is, Susan. It all comes down to depending on you.’

‘It’s much safer than the island,’ said Susan, and the others looked at her most gratefully. ‘No night sailing or anything like that, even if we wanted. Nothing can go wrong.’

‘If only it wasn’t so far,’ said Mrs Blackett.

‘You’ve got Rattletrap,’ said Nancy.

THE PIGEON-LOFT

‘Atkinson’s farm’s close to High Topps,’ said Nancy. ‘You can see it on the map in Captain Flint’s room. It’s only just across the Dundale road.’

‘And water?’

‘There’s the beck right on the Topps. We’ll camp by the side of it, where the charcoal-burners were. Simply gorgeous, it’s going to be.’

‘Oh well,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘But it’s no good thinking I can keep coming up there to see you. One of you’ll have to run down every day, to let me know no necks are broken or ankles twisted or anything like that.’

‘What are the pigeons for?’ said Nancy joyously.

‘But I can’t spend all day in the stableyard watching for a pigeon when I’ve five hundred thousand things to do and workmen in every room, and Cook and me both run off our legs.’

Nancy looked sharply at Dick.

Dick, in spite of himself, turned a little pink. ‘I think it would work,’ he said. ‘I think I could make the pigeon ring a bell when it came home.’

‘That would settle it,’ said Nancy.

‘No it wouldn’t,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Somebody would have to spend all day listening for the bell.’

‘It wouldn’t just ring and stop,’ said Dick. ‘The way I’ve planned it, it’ll go on ringing and ringing till somebody comes and turns it off.’

Mrs Blackett, yielding, caught at a straw. ‘If you can promise to send a pigeon home every day with a letter, and arrange for it to ring a bell that nobody can help hearing …’

‘Dick’ll do it,’ said Nancy. ‘That’ll be a pigeon a day for three days, and then one of us’ll come home to bring them back. Well done, Mother. A pigeon a day keeps the natives away. … We don’t want to keep you away, of course. It’s only to save you having to come.’

‘Well, if Dick really can do it,’ said Mrs Blackett doubtfully. ‘And if you can get milk at Atkinson’s, and find a nice place with good water. …’

‘She’s agreed,’ shouted Nancy. ‘Barbecued billygoats, Mother, but I thought you were never going to.’

‘I put all my trust in you, Susan,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘And you, too, John,’ she added. John grinned. It was kind of her to say it, but he knew she did not mean it. On questions of milk and drinking-water and getting able-seamen to bed in proper time, Susan was the one the natives trusted.

‘We’ll start the trek first thing in the morning,’ said Nancy.

‘No. No. No,’ said her mother. ‘You can’t do that. Send out your pioneers and find the right place. Make sure about the milk from Atkinson’s. They may be selling every drop they have with so many visitors about. And make sure of good water. You know what the becks are like and the Atkinsons may be short themselves. I can’t have you simply setting out with nothing arranged. And Dick’s got to turn your pigeons into bell-ringers or you can’t go at all.’

‘Oh well,’ said Nancy. ‘It won’t really be waste of time. John and Susan’ll come and see for themselves and the others can be getting things ready. Someone’s got to go to Rio to buy hammers. Torches, too, and a tremendous lot of stores.’

The rest of the evening passed quickly in feasting and planning.

‘Not all mining camps have such good cooks,’ said Mrs Blackett, sitting by the camp fire after supper.

‘The pemmican would have been better with a little chopped onion,’ said Susan, ‘but I didn’t think of it in time.’

‘I do hope I’m not doing wrong,’ said Mrs Blackett, as at last she left them, and they walked with her across the lawn in the dusk and said their good nights at the garden door.

‘You’re doing exactly right,’ said Nancy.

‘I mean what I say about those pigeons,’ said Mrs Blackett, almost hopefully. ‘They’ll have to ring bells if I’m to agree to your going.’

‘They shall,’ said Nancy.

‘Don’t sit up late.’

‘Just till the flames die down.’

They walked slowly back to where the embers of the camp fire were glowing behind the bushes.

‘You really think you can do it, Dick?’ said Nancy.

Dick pulled his torch from his pocket and turned it on. ‘I’ll just go and make sure,’ he said.

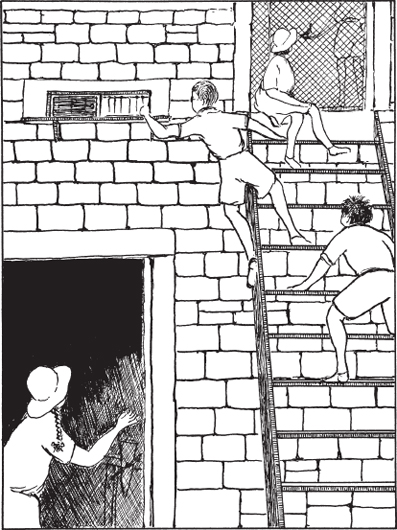

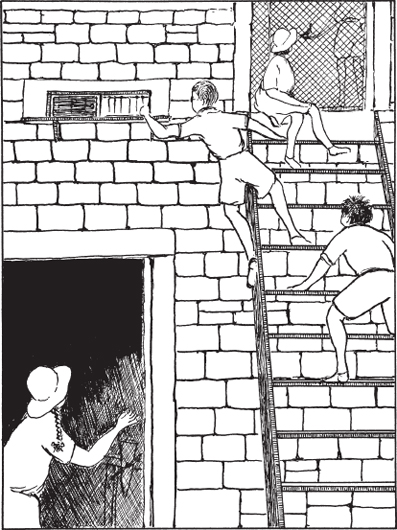

Very quietly they went into the stableyard. Dick climbed the ladder to the pigeon-loft, leaned across and laid his torch on the pigeons’ landing-place, and felt the swinging wires. There was a sudden fluttering in the loft.

‘Phiu … phiu … phiu …’ Peggy and Titty were making noises to reassure the pigeons.

‘I think it’s all right,’ said Dick. ‘The wires are all separate, aren’t they? We’ll have to fasten three or four of them together.’

‘What are you doing?’ Mrs Blackett called from an upper window.

‘Just making sure about something,’ said Nancy. ‘Good night, Mother. We’ll all go to bed right away.’