ROGER IN THE MINE

19

Roger Alone

‘SQUASHY’S GONE.’

‘Not really?’ Titty, from the foot of the ash tree, was looking up at Captain Nancy who was high in its branches and looking out.

‘He has,’ Nancy called down. ‘He’s gone off down the road. We’ll have the Topps to ourselves again.’

Titty ran back into the camp.

‘Nancy says he’s gone down the road. …’

‘Let’s get breakfast over quick,’ said John, who had just got back from Tyson’s with the morning milk.

A moment later Nancy slid down the last few feet of the look-out tree and rubbed the green lichen stain from her knees. Twenty minutes after that, the eight of them were already spreading out in a long line and beginning a new day’s combing of the Topps. With Squashy Hat gone the other way, down the road, perhaps, indeed, round the head of the lake to Rio, they meant to take their chance and cover all the ground they could.

But, for one reason or another, it was a duller morning’s work than usual. They found only two old workings to look at, and neither of them even looked as if it might be the one of which Slater Bob had spoken. Both tunnels were in a broken-down state, and John and Nancy let none of the younger ones go inside. Titty’s ball of string was left unused. Roger grew more and more bored. Even Titty began to think it a pity there was no scouting to be done. Dorothea now and then looked regretfully towards the white splashes on the hillside. What sort of a story was it when it was without a villain? Dick alone, for whom, at the moment, nothing mattered but different kinds of stones, kept his hammer busy and was happy.

At noon they were back again at the near side of the Topps. This was according to plan, and they ate their midday dinner, pemmican (cold), apples, bunloaf and marmalade, and a bottle of ginger beer (grog) apiece, in the shade of the trees. They sent off Sappho early, to give her plenty of time to get home. The message was cheerful: ‘ALL GOING WELL.’ Roger thought it much too cheerful considering there was more than half the Topps still to be searched.

In the afternoon they started again on another strip of country, and worked their way across to the foot of the Screes. There was a little more interest this time, because they had several stony ridges to cross, and little valleys and ravines in the Topps, where they found heather and grey rock together. But though this seemed very hopeful, they found no signs of old workings, and when, towards evening, after moving north so as to cover fresh ground, they started to work back again towards the valley of the Amazon, Roger was almost in a state of mutiny.

They were not half-way across the Topps when he invented a private game. He looked right and left along the line of prospectors. Nobody was as hopeful as in the morning, and the line was not as straight as it had been. Some lagged, others were going too fast, and the line curled this way and that among heather and bracken and rock as they made their way slowly home. Still, a line there was, and Roger thought that it would be rather good practice for scouting if he were to try to get from one end of it to the other without being seen. Nancy, whose eyes were sharpest, was luckily on his left. All the others were on his right. He took a good look across country. There were John, Titty, Dorothea, Peggy, Dick and Susan. He noted things likely to be useful, a patch of rocks, a gully, and, best of all, a wide stretch of bracken, not twenty yards ahead of him and stretching away over the Topps, nearly as far as the rocky ridge over which Dorothea was scrambling on her hands and knees.

Roger waited at the edge of the bracken. Nobody was looking his way. Now was the chance. Good. There was an old sheep track through the bracken. Roger looked round once more, and, a moment later, supposing people had happened to look that way, they would have seen nothing but a slight stirring of the bracken tops.

He had passed behind both John and Titty and lay at the edge of the bracken, peering out to see what had become of Dorothea. There she was, close to him. Roger lay perfectly still. Almost he had come out in front of her, when even Dorothea would have seen him. She had left the rocks and was walking slowly across some open ground, talking aloud. Perhaps she, too, was getting a little tired of prospecting. ‘The outlaw saw his chance, and, hidden by the dusk, passed unseen within a stone’s throw … within an arrow-shot – no … passed between his enemies so close that they might have touched him.’ Just for a moment Roger thought that Dorothea had discovered him and was talking like this to let him know she knew what he was doing. Then he remembered The Outlaw of the Broads and knew that Dorothea, while prospecting with the others, was also busy on a chapter of her book.

From where he lay, no one else was in sight. He let Dorothea get a little further from him, and then, low to the ground, slipped behind the rocks she had just crossed. Here he rested in a good place from which he could look out and see what all the others were doing. He had Peggy, Dick and Susan still to pass. That ought to be easy enough, he thought, once he had worked across this rocky bit and got into the heather. All three of them were prospecting hard. He watched them for some time. Not one of them ever looked back. They were going steadily ahead.

Roger looked round towards the others, Dorothea, Titty, John and Nancy. He could keep this lump of rocks between himself and them nearly all the way to the heather. He set out once more, dashed across a bit of open ground and lay low for a moment to take his breath and listen. No, Peggy had not seen him. There she was, pushing her way through some bracken, in a hurry to get to the next stony patch where there might be a chance of finding something. Roger was on his feet again, and slipped over another twenty yards to lie behind a rock. Then came a long awkward bit where he could not safely even lift his head. He crawled, flat on his stomach on the dried-up grass. This was real stalking. Much better fun than prospecting. He wished Titty was in it too. Hullo. What were Dick and Susan doing? Had they found something? They had stopped and were close together, looking at some rocks. Bother them. How could a stalking Indian slip past behind them if instead of moving forward they just stuck in one place. Roger waited. And still Dick and Susan did not move. Roger’s patience gave out. Of course, it was taking an awful risk, but once he could get into the heather he might manage to get across in front of their very noses without being seen.

He was in the heather, worming his way along an old sheep track. The heather, already showing purple, had all but overgrown the track, so that Roger, crawling on his stomach, had to push his way through. There was a steady buzz of bees at the opening flowers. A twisted root of heather in the track reminded Roger of the adders that all this time he had forgotten. Well, it was no good thinking of banging with a stick, because he had not got one, and anyway the one thing an Indian must not do is to make a noise.

Roger made up his mind not to put his hand anywhere without first making sure that he was not going to put it on a sleeping snake.

He met no snake, but was watching for one so carefully that he forgot his stalking and everything else, and was startled almost into squeaking when right in his face, not a yard in front of him, an old cock grouse got up, with a whirring of wings like the sudden running down of a gigantic clock and a loud ‘Go back! Go back! Go back!’ as it flew away over the heather. It was more like an explosion than a bird. Roger half jumped up, bit his tongue most painfully, and dropped to the ground again just in time. He heard Dick’s voice.

‘Something startled that grouse. Did you see what it was? It couldn’t be a dog.’

Dick’s voice seemed to come from a little to the right and in front of him. Voices carried so well on that clear still day. Roger would have given a good-sized bit of chocolate to know just how far ahead of him Dick was. But he dared not lift his head above the heather. Dick had noticed the grouse and must be looking at the very place. It would be just like him to come through the heather to find out what it was that had made the grouse get up. The only thing to do was to hurry on without shaking the heather and to hope that there were no more grouse.

The sheep track did not run straight, and five minutes later Roger was wishing he had a compass. ‘At least,’ he said to himself, ‘not exactly a compass so much as a periscope, so that I could poke it up out of the heather and look round without being seen.’

And then, suddenly, the heather came to an end, and Roger, on all fours, found himself looking out over a hollow in the moor. The rocks dropped sharply away beneath him to a grass-covered bottom. On the other side of it rocks rose again. Beyond the hollow he could see far away to the edge of the Topps, and the Great Wall, and the uppermost branches of the look-out tree above the hidden camp.

Steps sounded, and the noise of people pushing through the deep heather not twenty yards behind him. It was no good waiting until they trod on him. Roger began working down to the bottom of the hollow, holding on by the heather that grew in the cracks of the rocks. At any moment the other prospectors might be looking down upon him from above. Half-way down he slipped. As he fell, he rolled over, caught at a clump of heather, and found himself hanging from it, a foot from the ground. Small stones clattered by. He let go of the heather and dropped and found himself looking into a dark three-cornered hole in the rock. This was better than anything he could have hoped. He crouched in the mouth of the hole, and looked up, to see nothing but rock and the heather from which he had been swinging. The heather had sprung back. No one looking down from the top could see him. …

He was only just in time.

‘Did you hear that?’ Dick was asking. ‘Why, hullo, here’s another of those ravines.’

‘This is the one we saw this morning,’ said Susan. ‘We’ve been here. We’ve got too far to the right. My fault, calling you over to look at those stones. Look. We’ve got much too far from Peggy. Push away to the left. No good going over the same ground again. …’

‘Aye, aye, sir.’ That was Dick’s voice, close above him, and Roger grinned to hear Dick talk in the manner of ship’s boys and able-seamen.

They were working through the heather away to the left, and presently would be able to see the whole length of the gully. Roger pulled his torch out of the stern pocket of his shorts. What sort of a hole was this that he had found just when he needed it? He flashed the torch into the darkness. He saw at once that it was one of the old workings, and a very old one. Inside the hole there was a tunnel that opened after a few yards into a small cave, much like Peter Duck’s cave in Swallowdale. It went no further. That was why no one had noticed it this morning. Most of the old workings were easily found because of the lump outside them, often covered with turf, but still unnatural, built up out of the waste stuff that the old miners had brought out of the rock. This working had been abandoned almost at once, the little pile thrown out had been scattered about the bottom of the gully, or maybe taken away and used for walling a sheepfold. There had been nothing left outside to show that the entrance was more than a dark shadow under overhanging rocks.

Roger, with torch lit, moved on tiptoe about the inner cave. He was safe here. Susan and Dick could walk right past without suspecting. No one would ever guess how he had managed to vanish so completely. He crept back to the mouth of the cave and listened.

From somewhere far away on the left, he heard a faint ‘Ahoy!’

‘Ahoy! Ahoy!’ Susan and Dick were answering. Yes, they had passed the end of the gully. There was nothing in those ‘Ahoys’ that meant anything to interest Roger. Nobody had noticed he had gone, or there would have been a different note in Susan’s voice. Nothing had been found or there would have been a different note in Dick’s or Peggy’s. These were the ‘Ahoys’ of disheartened prospectors, just calling to each other for company’s sake in the wilderness. No use showing himself just yet, or they would not realise what a gorgeous bit of Indianing he had done. No use appearing before anybody had missed him.

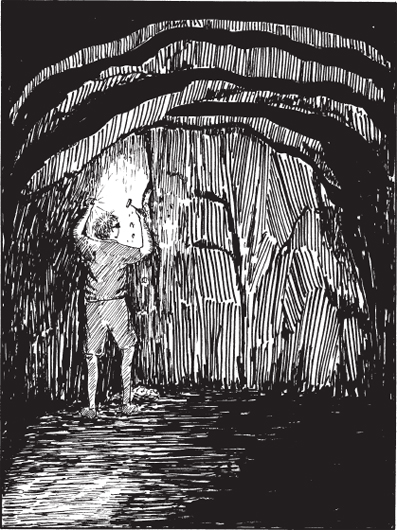

He went back into the cave to think out a really good use for it. It was a pity Titty was not here, but, after all, if she had been, it would have been her discovery as much as his. And it was just about time, Roger thought, that he ought to begin discovering things for himself. He flashed his torch over the rocky ceiling and chipped sides. Hundreds of years ago people had been working here. He thought of Slater Bob, all alone in the middle of Ling Scar, working away by himself. It was easy to pretend that the few yards to the mouth of the cave were really half a mile or even more. A little light came in from outside. That could not be helped. ‘Oh, well,’ said Roger to himself, ‘that could be from one of those big lamps somewhere just round the corner.’ Rather a good thing, on the whole, because it let him save his torch, now that his eyes were growing accustomed to the darkness. What about doing a little mining now that he was here? Slater Bob did not just sit in the middle of the hill doing nothing. Roger pulled out his goggles, put them on, and struck the wall of the cave a smart blow with his hammer. The noise was much greater than he had expected, though the stone did not even chip. Would they have heard that noise outside? He waited a minute or two, listening. Then he tried again. Then, with his torch, he began looking round the walls for a place to hit where he might have some chance of breaking off a bit of stone. Not much fun in hammering a rock when nothing happens. At the extreme inside of the cave he found a crack running not quite straight up and down, but very nearly so. Holding the torch in his left hand, he hit out with the hammer in his right. A bit of rock flaked away.

‘Not quite so hard here,’ said Roger to himself, and took another whack or two up and down the crack. More rock came away. ‘Slater Bob’s pretty strong,’ said Roger, and let fly again. Rock was falling round his hand in small bits. He saw another crack close by the first. Had it been there before or had he made it? This was real quarrying. He hit away at the rock between the two cracks, and stepped back with a squeak. A bit of rock as big as a Latin dictionary had come loose. Roger jumped clear as it dropped, but a smaller bit that came with it hit his ankle.

‘Ow,’ said Roger, and bent to rub the place.

That was enough. He would leave quarrying to Slater Bob. And then, as he stooped and rubbed his ankle, and shone his torch on it to see if the skin was broken, which it was not, he caught a sudden glint from among the stones at his feet.

ROGER IN THE MINE

He tore off his goggles to make sure. It could not be, and yet … He picked up a scrap of rock and took it to the daylight at the mouth of his cave. He came back and peered into the place from which the big lump had fallen. He pushed his torch in there to get a better look. He turned to get out of the cave and to go shouting across the Topps after the others. But no. There would be plenty of time for that. After all that combing of theirs. … Let them wait. … There was plenty of life in his torch yet. All thoughts of Slater Bob forgotten, torch in one hand and hammer in the other, Roger set to work in earnest. Chips of stone flipped him on the cheek. He put the goggles on again to save his eyes. Nothing else mattered. In there, in the hole that he had made, was something that was going to come out, or Roger Walker, gold-miner, would know the reason why.