21

Staking Their Claim

‘SHOW A LEG, my hearties!’

Nancy woke the camp with a cheerful shout. The prospectors leapt to life. Everybody was awake and busy by the time she was half-way down to Tyson’s with the milk-can. She astonished Mrs Tyson by reaching the door of the dairy almost before the milk was brought in. By the time she was back at the camp, all faces had been washed, teeth cleaned, beds made and tents tidied. The kettle was already boiling. Breakfast was the quickest meal they had ever eaten. They even used cold water to cool their tea because it was too hot to drink. Peggy took her apple up the ash tree and reported that Squashy Hat must be still in bed. John, between mouthfuls, sharpened a stout stick. If there was a claim to be staked it was just as well to have things ready. It was no good thinking there were sticks to cut on the Topps. Nancy watched him for a moment, and said, ‘We’ll want a good-sized bit of paper.’ Dorothea dived back into her tent and came out with an exercise book.

‘Will this do?’ she asked.

Nancy looked at it and saw The Outlaw of the Broads printed on the cover.

‘It’s all right,’ said Dorothea. ‘There’s nothing inside this volume yet.’

‘Look here, Dot,’ said Nancy. ‘We’ll get you another in Rio. …’ and then she hesitated. After all, Roger was Roger. ‘I won’t tear any leaves out now,’ she said, ‘but bring it along, just in case it’s needed.’

Today even Susan was ready to put off washing up until a little later, and the whole expedition set out across the Topps.

Roger, for once the leader, was the least hurried of the party. The others kept pressing round him, as if the nearer they kept to him the sooner they would see the place for themselves.

‘Can you see it now?’ asked Nancy.

‘It’s beyond those rocks.’

‘Which rocks?’

‘Those.’

‘But there are rocks all over the place.’

‘It’s beyond the ones I’m looking at.’

‘Oh go on, Rogie,’ said Titty. ‘Do tell us what to look for.’

‘There’s nothing to see till we get there,’ said Roger, and kept steadily on at his own pace.

Presently he walked a little slower, and then stopped, and looked about him.

‘Don’t say you’ve gone and forgotten where it is,’ said Peggy.

Roger grinned.

‘Don’t be a donk,’ said John. Both he and Titty had seen that grin and known that Roger had fished for Peggy and caught her.

‘Well, I might have forgotten,’ said Roger. ‘It was jolly dark before I got home.’

They walked on over that rolling, rocky country, which had changed in the night for all of them. It was no longer a country to be searched by long, laborious combing, with everybody out in a row. Roger had almost come to hate it by the time he had given up being a tooth in the comb and begun a little Indian work of his own. Today it seemed altogether different even to him. Gold had been found, and he had found it. No more combing for anybody. The only thing they had to do was to gather up the nuggets. Or was there more to do?

The others were cross-questioning Dick as they walked along, and Dick was showing Nancy a paragraph in the metallurgy book.

‘Crushing and panning,’ she was saying. ‘We’ll have to do that anyhow, to get the gold by itself. Jolly good thing we brought Captain Flint’s crushing mill.’

‘It won’t be an ingot even then.’

‘A nugget,’ said Titty.

‘Of course not,’ said Nancy. ‘Gold dust.’

‘And what then?’

‘Slater Bob’ll show us how to make it into ingots. We must have at least one ready for Captain Flint.’

‘We might make him a pair of gold earrings,’ said Titty. ‘Like Black Jake had in Peter Duck.’

‘He’d never wear them,’ said Peggy doubtfully.

‘A good big shiny blob to hang on his watch-chain,’ said Nancy.

‘And enough to make a gold collar for Timothy,’ said Dorothea.

There was a sudden melancholy pause.

‘If he isn’t dead,’ said Peggy at last.

‘It’s weeks since that telegram came,’ said Nancy grimly, and then suddenly shaking off her momentary gloom, ‘Oh well, if he’s dead he’s probably been dead ages, and been sunk to the bottom of the sea.’

‘Wrapped in a Union Jack,’ said Dorothea.

‘Suffered a sea change,’ murmured Titty, ‘rich and rare … probably coral. …’

‘Anyway we can’t do anything about it,’ said Nancy. ‘And the gold’ll console Uncle Jim a bit, or it jolly well ought to. … Though you can get awfully fond of things like armadillos. … Oh Giminy. … It can’t be helped. Look here, Roger, how far now?’

‘Nearly there,’ said Roger.

‘But we’ve searched every bit of this.’

‘I know,’ said Roger.

A minute or two later he stopped short, looking down into the narrow little valley.

‘But we’ve been here,’ said John.

‘I told you you had,’ said Roger. ‘But it’s here all the same.’

‘It’s the place you said was just like Swallowdale,’ said Dorothea to Titty.

‘So it is,’ said Titty. ‘Only there’s no beck, and no cave.’

‘There’s a cave all right,’ said Roger.

At his first glance he had almost doubted whether this was indeed the place. Just for one moment he had had a panicky fear that he had brought them to the wrong valley, that he had found his cave only to lose it. Then he saw the place where he had slid down on the further side, the heather with which he had broken his fall, the dark shadow below it.

‘Here it is,’ he said.

‘But where?’ said Nancy.

‘Don’t be a donk,’ said John. ‘Where is it?’

Roger was scrambling down into the ravine. He thought of wandering round and seeing how long it would take them to find the hole, but decided it wasn’t really safe. Nancy had been waiting long enough already. So he walked straight across the ravine, and before he was half-way across the others had seen it. There was a general rush. John and Nancy jostled in the hole.

‘In there?’ said Peggy.

‘Roger, you didn’t go in,’ said Susan.

‘Jolly lucky I did,’ said Roger.

‘Look! Dick’s got a bit,’ said Dorothea.

‘I must have dropped it coming out,’ said Roger.

‘Hurry up, Susan,’ said Peggy.

‘Oh, look here,’ said Roger. ‘Play fair. I found it,’ and he shot into the opening after Susan.

The cave left by the miners of long ago seemed a good deal smaller now, with eight prospectors bumping about inside it and seven torches sending bright round patches of light over its rough hewn walls and roof. It had seemed quite large the day before to Roger, alone in it, with a single torch with which he could not light up more than a small bit of it at a time.

‘It’s the smallest of all the ones we’ve seen,’ said Peggy.

‘So long as it’s the right one,’ said Nancy. ‘But look here, Roger, where is that quartz?’

‘Perhaps there was only that one bit,’ said John.

‘You’ve got to hammer for it,’ said Roger. ‘I didn’t see any till I did.’

Torch after torch flashed on the rocky wall at which he was pointing. There was a general shout. On the ground under the wall were chippings of quartz and a lump or two of grey stone, and above the chippings they could all see that it was as if two rocks had been pressed together sideways to make a sandwich with a thin layer of quartz as the potted meat between them. The crack ran almost straight up and down, and in it, beside the white gleam of the quartz under the light of the torches, there was the yellow sparkle of metal.

‘Giminy,’ cried Nancy. ‘He’s found it all right. Look out, John, with that hammer. Let’s get a fair whack at it.’

In the general rattle of hammers up and down the narrow vein it was lucky nobody got hurt. Bits of stone and quartz were flying in all directions.

‘Do take care,’ said Susan. ‘Put your goggles on. … If a bit gets in somebody’s eye!’

‘That’s my nose,’ said Roger.

‘Sorry,’ said Peggy.

‘There’s gold on almost every bit,’ said Dorothea.

‘Quartz is jolly hard stone,’ said Titty.

‘So is Peggy’s elbow,’ said Roger, very tenderly feeling his nose. ‘Not broken,’ he admitted, ‘but it easily might have been.’

‘Look here,’ said John after a few more minutes of hammering. ‘This is waste of time. We ought to be using dynamite.’

‘Oh good,’ said Roger.

‘Captain Flint’s got some gunpowder,’ said Peggy.

But for once Nancy was not for going to extremes.

‘Captain Flint’ll do the dynamiting,’ she said. ‘He’ll simply love it. And we’ll all help. But it’s no good wasting any of the blowing up and all that before he comes. It’s that that’s going to keep him at home. He didn’t like us letting off that firework on the roof of his houseboat, but he likes blasting as much as anybody. …’

Susan was much relieved. ‘Fireworks are all very well,’ she said, ‘but dynamite …’

John was a little disappointed.

‘We don’t need it,’ said Nancy. ‘The more blasting we leave him to do, the better he’ll be pleased. All we’ve got to do is to show him there’s something worth blasting for. …’

‘There’ll be no holding him,’ said Peggy, ‘as soon as he sees this.’

‘Well, it’s no good just batting at it,’ said John. ‘Waste of time. We want chisels. … And what about the crushing and panning?’

‘We’ll want a bucket for water,’ said Dick. ‘And something shallow for the panning.’

‘Frying-pan’s the very thing,’ said Nancy.

‘I’ll go to Tyson’s for chisels,’ said John.

‘A bucket for water … the crushing mill … frying-pan. … Don’t let’s waste another minute,’ said Nancy.

They hurried out into the ravine, tore off their goggles, and stood blinking in the sunshine, comparing the golden, glittering specks on different bits of quartz.

‘Slip up and scout, somebody,’ said Nancy.

Roger was already climbing up. He stopped well above their heads. One foot kicked in the air.

‘He’s seen Squashy,’ said Titty.

‘He’s just going up on the Screes,’ Roger whispered hoarsely.

‘Pretending,’ said Titty, ‘and then he’ll jump our claim the moment we’re gone.’

‘Golly,’ said Nancy, ‘and we haven’t staked it yet. Dot, we’ll have to use that paper.’ She pulled her blue pencil from her pocket.

Dorothea tore a page from her exercise book. ‘Won’t you put the book under it to write on?’ she said.

Roger came sliding down to see.

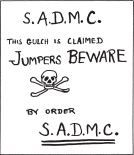

Nancy, pressing the exercise book against the face of the rock, wrote in big capital letters.

‘S.A.D. MINING COMPANY.’

‘What does it mean?’ said Roger.

‘Swallows, Amazons and D’s Mining Company, you bone-headed young galoot.’

‘But why sad?’ asked Roger, skipping hurriedly out of reach.

Nancy laughed and scrumpled that leaf up.

‘Sorry, Dot,’ she said, ‘I’ll have to take another, just in case there are more donks about.’

On the second leaf she wrote ‘S.A.D.M.C.’ and waited, blue pencil in air.

‘Trespassers will be prosecuted,’ murmured Roger.

‘It isn’t trespassers that matter,’ said Titty. ‘It’s jumpers. If Squashy tried to jump our claim …’

‘We’d jolly well kill him,’ said Nancy.

‘Well, let’s say so,’ said Roger.

But both John and Susan were against this.

‘It’s no use threatening something you can’t do,’ said John.

‘Don’t say what we’ll do,’ said Susan.

‘What about “All rights reserved”?’ suggested Dorothea.

But Nancy was busy again with her blue pencil.

‘How about that?’ she said at last, and held up the notice she had finished.

‘Jolly good,’ said John. ‘We don’t want to worry ordinary decent people, only jumpers. No one will know what it means unless he’s someone we want to frighten off. And he won’t know what on earth is going to happen to him. Far better than saying he’ll be hanged or anything like that. …’

‘Things worse than death,’ Dorothea tasted the words with relish.

‘So long as he thinks it’s something pretty unpleasant,’ said Titty.

John began working a hole in the ground with the point of his stake.

‘Not there,’ said Nancy. ‘Much too near. We’ve claimed the whole gulch. Supposing he does come snooping along there’s no need to show him the way into our mine. He may never see it. You know, we never spotted it ourselves first time.’

John used a stone to drive the stake into the ground in the middle of the little valley. He split the top of it with a knife and wedged in the notice.

‘Three cheers for Golden Gulch,’ said Nancy. ‘Not too loud. … Come on now and get the things. No need for everybody to come. The able-seamen stay on guard. We’ll do the carting.’

The captains and mates climbed the side of the Gulch and were gone.

‘I’ll just make sure what he says about crushing,’ said Dick, and settled down to frantic study of Phillips on Metals.

‘Let’s get some more of the gold,’ said Dorothea.

Titty and Roger followed her back into the mine.

‘Gosh,’ said Titty. ‘What a blessing you found it.’

‘No more combing, anyhow,’ said Roger.