CHARCOAL PUDDING

28

Charcoal-Burners

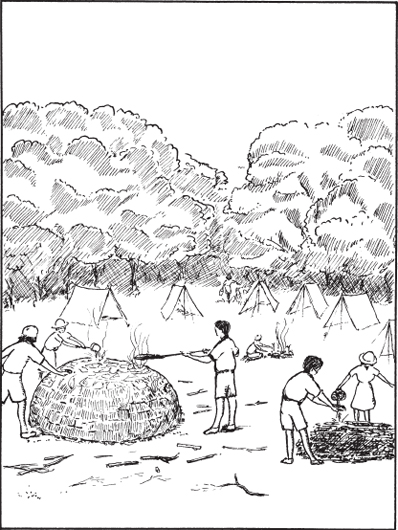

BREAKFAST WAS OVER. Work had begun again. Susan was by the well, washing up. Roger was looking out from the top of the ash tree. Dick was alone in the camp. If he had not been so intent on what he was doing, he could have heard the noise of the wood-cutters. They needed a little more wood to finish the charcoal mound, which looked just now like a cake made of sticks all pointing towards the middle, a cake with a slice cut out of it. The others were busy getting wood to fill in that missing slice.

But Dick heard nothing. He was lying on his stomach on the ground using his new blowpipe to drive the flame of a candle into a tiny hole he had scraped in a bit of charcoal left on the pitstead by the real charcoal-burners of long ago. The edges of the hole turned first red and then white with heat. He stopped to take breath. Dipping the blade of his knife into the cocoa tin of gold dust, he lifted a little on the tip and put it in the hole on the charcoal.

‘It ought to do now,’ he said to himself, aloud, though he had not known he had spoken at all.

A shadow fell across his hands. Titty and Dorothea had dumped a load of wood by the mound and were watching him.

He looked up with eyes that hardly saw them.

‘Shall I go and fetch Nancy?’ said Dorothea.

‘Not till there’s a bubble of gold,’ said Dick.

He took a long breath and started again. His cheeks were blown out to hold as much air as he could and let him keep up a steady blast through the pipe even while he was breathing in through his nose. The flame made a hissing noise. Again the charcoal round the hole turned red, then glowing white. The little pile of gold dust darkened.

‘It’s all running together,’ said Dorothea.

‘Melting,’ said Titty.

The dust was gone. In its place was a tiny red-hot drop.

Dick blew on and on. The glowing drop moved in the hole, driven round it by the jet of candle-flame.

‘He’s done it,’ cried Dorothea.

‘It’s a baby nugget,’ cried Titty. ‘Come and look.’

John and Nancy threw down their armfuls of sticks and crossed the camp on the run.

‘Giminy,’ said Nancy.

Dick stopped blowing. The sweat was standing on his forehead. He put blowpipe and charcoal carefully down, rolled over, sat up, took off his spectacles and wiped them and put them on again. The charcoal was cooling. The little glowing drop turned darker and darker.

The others looked at him with a question. What had happened? They had all thought that as it cooled it would be a tiny nugget of shining gold. It was dull, dark, almost black.

‘Something’s gone wrong,’ said Dick.

‘Perhaps it’s just dirt on the outside of it,’ said John.

Dick burnt the tip of his finger, and then used the tip of his knife instead, in getting the little dark drop out of its nest in the charcoal.

‘It’s too small to scrape,’ said Nancy. ‘What about cutting it in half to see the inside?’

Dick worked the little dark drop off the charcoal on a flat stone. It was so small that it was not easy to use the knife on it. Twice it nearly rolled off the stone to be lost altogether. Then it stuck in a crack and Dick got the edge of his knife across it and pressed. It broke up into dark powder.

‘Funny,’ he said. ‘It melted all right.’

‘I bet it got mixed up with the charcoal,’ said Nancy. ‘You said yourself it ought to be in a crucible.’

‘Of course, it wasn’t a very clean bit of charcoal,’ said Dick, but he said it very doubtfully.

‘Anyway, it’s not much good trying with just a pinch,’ said Nancy. ‘You’ll see, it’ll be quite all right when we do it properly.’

‘The book does say a crucible.’

‘Let’s get on with the charcoal-burning,’ said Nancy. ‘And there’s the furnace to build, too. We’ll be smelting the whole lot tomorrow and have a nugget as big as my fist. Golly, Roger, you did give me a start.’

‘Ahoy!’ Roger’s shrill yell sounded again from the top of the ash tree. ‘Ahoy! He’s just coming out of the farm.’

‘Two scouts to the gulch,’ ordered Nancy. ‘Roger can go. And Titty. Head him off if he looks like jumping. Signal if you need help. We’ll keep a look-out. Skip along and get there first.’

‘Where’s he going?’

‘He isn’t coming here.’

The scouts whispered to each other, their bodies in the gulch, their heads just high enough to see out over the edge.

Squashy Hat, after a short visit to the lowest of his white spots, was walking across the Topps in the direction of Ling Scar. For a long time they watched him, walking on and on, till he came to the foot of the ridge.

‘He’s going through the tunnel to see Slater Bob,’ said Titty.

‘He can’t,’ said Roger.

‘He doesn’t know that yet,’ said Titty.

‘I wonder if he knows which hole to go in at.’

Squashy Hat seemed to have no doubts about the hole. Up he went, and then, just where he had startled the watchers of two days before by suddenly appearing, he was gone.

‘Not for long,’ said Roger. ‘This time he’ll be more like a Jack-in-the-box than ever.’

They could not from the gulch see the hole in the hillside, but they could see the rocks round it and knew exactly where it was. They watched. Minute after minute went by.

‘He can’t be digging his way through,’ said Titty.

‘Another good dollop may have come down on the top of him,’ said Roger hopefully.

‘Oh no, no,’ said Titty, pushing away the horrible idea. Squashy Hat might be a rival. He might be in league with Slater Bob. He might be a possible jumper of claims. But, no matter, Titty was content to let him go in peace. ‘Oh, it’s all right,’ she said. ‘There he is.’

‘Pretty mad, I bet,’ said Roger.

Squashy Hat seemed to have got his clothes very dirty. They saw him take his coat off and shake it and do his best to clean it with a handkerchief. Then they saw him trying to tidy up the knees of his trousers.

‘Fallen down in the tunnel,’ said Roger, with a note of satisfaction rather than of pity.

‘What’ll he do now,’ said Titty.

He was not long in making up his mind. Flinging his jacket across his shoulder, Squashy Hat turned to the ridge and began climbing up it just where, two days ago, four able-seamen had come racing down.

‘He’s got something to say to Slater Bob,’ said Titty. ‘I wonder what he’s found out. I expect he was blowpiping all night.’

‘He’ll be pretty hot by the time he gets to the top,’ said Roger.

Squashy Hat went slowly up the steep side of the ridge. The watchers at the edge of the gulch had no need of the telescope. His shirt made a white speck that was easy to follow. Up and up it went, stopping a moment while the climber rested, going on again, up and up, disappearing in gullies of rock and heather, showing again on the further side of them, always higher and higher, until at last it reached the skyline and was gone.

For a minute or two they watched the empty hillside. Then Titty jumped up.

‘Come on, Roger,’ she said. ‘Let’s go and report.’

‘Good,’ said Nancy, whom they found with Dick, busy with spades at the top of the Great Wall. ‘Probably his blowpiping went wrong, too, and he’s gone over to ask Slater Bob about it.’

‘I wish we could,’ said Dick.

‘What are you doing,’ said Roger. ‘Gardening?’

A long wide strip of rock at the top of the Great Wall had been cleared of turf. The earth was thin there, and easy to lift with a spade. They watched Nancy slide her spade under the turf, turn it over, and cut it into square clods. A pile were already waiting.

‘Crust for the charcoal pudding,’ said Nancy. ‘Go on. Take as many as you can. Carry them down and you’ll see.’

Dick helped to load them and they staggered off down the gully to the camp, meeting Peggy and Susan coming up for another lot.

The charcoal mound was looking altogether different. The missing slice had been filled in, leaving only a small tunnel along the ground leading to the middle of the mound. The top of the mound was already covered with turfs like those they were carrying. John, stretched full length, was reaching through the tunnel.

‘It’s all right this time,’ he said, pulling his arm out and getting up. ‘The tunnel fell in twice.’

‘Shall we put these bits of crust on, too?’ said Roger.

‘Get them damped first,’ said John. ‘Put them down with the others.’

At the side of the charcoal cake which had thus turned into a charcoal pudding were rows and rows of clods ready for use. Dorothea came out of the trees from the well with the kettle.

‘Oh good,’ she said, pouring water on the clods. ‘But the well’s getting rather muddy with me dipping so often.’

‘Can’t be helped,’ said John. ‘We’re nearly ready for lighting. Look out, Roger, don’t kick those sticks away. They’re waiting to be crammed into the tunnel after we’ve got it going.’

Susan, Peggy, Dick and Nancy came down into the camp, each with as many of the cut turfs as they could manage.

‘Got about enough, haven’t we?’ said Nancy. ‘How’s the tunnel now?’

‘All clear,’ said John.

Nancy pulled out a box of matches.

‘Go on, John,’ she said. ‘You’ve got the longest arm.’

John lay down again, lit a match and worked his arm into the tunnel.

‘It’s gone out,’ he said.

He tried another.

‘Why won’t it light anywhere?’ asked Roger.

‘Green wood,’ said Dick. ‘He’s got dry leaves and sticks right in the middle.’

A third match went out.

‘We’ll have to open it out to start it,’ said Nancy.

‘It’ll go like a bonfire if we do,’ said John.

Dick was watching. Nancy saw his earnest face.

‘Spit it out, Professor,’ she said.

‘Couldn’t we make a torch at the end of a stick? What about dry moss?’

‘I know where there is some,’ said Roger.

He was back in a moment with a couple of handfuls. John tied the bundle to the end of a stick. He lay down again.

‘You light it, Nancy, and I’ll shove it in.’

The moss flared up. John plunged it into the tunnel. There was a sudden loud crackling from the middle of the mound. John reached for the green sticks, all cut to length, that were to fill up the tunnel. He jammed them in.

Smoke began to pour out through holes in the crust. The crackling grew louder.

‘Quick. Quick. … Slap them on,’ said Nancy.

‘It’s off,’ said Titty. ‘It’s off. It’s going to blaze in a minute.’

‘It jolly well mustn’t,’ said Nancy. ‘Quick. Damp turfs, not dry ones.’

Thick smoke was pouring from the mound. For a few desperate minutes it almost seemed that it would beat them. But with eight people stopping the leaks, the fire had but a poor chance. They closed up hole after hole until, at last, the charcoal mound under its crust of turfs, all with the grassy side inwards, looked like a dead heap of earth.

‘Have we put it out?’

‘I can still hear it,’ said Titty, listening with her head close to it.

‘Better open a hole or two,’ said Nancy. ‘They never shut it up altogether till the smoke changes colour.’

Here and there they lifted a clod, and the smoke poured out, tawny, greenish, choking.

‘It’s all right,’ said Nancy. ‘Getting hold properly inside. So long as we don’t let the whole pile flare up.’

‘What time is it now?’ said Peggy.

‘How long does it have to stay lit?’ asked Dick, pulling out his watch. ‘It’s nearly three o’clock. …’

‘Then it’s all right for anybody to be hungry,’ said Roger.

‘And I’ve got no dinner,’ said Susan. ‘Sardines, it’ll have to be.’

‘The charcoal-burners keep their mounds burning for weeks and weeks,’ said Peggy.

‘But we can’t,’ said Titty.

‘Not with all our natives coming,’ said Dorothea.

‘We can’t, anyway,’ said Nancy. ‘Uncle Jim – Captain Flint may be back at any minute. He may be back now. He may be just strolling up here to say howdy and us without an ingot to show him. There’s no need for more than a day either. Their mounds are big enough to cover the whole camp, and ours is tiny. … Ours ought to be properly cooked by tomorrow evening. All right, Susan. Trot out the sardines. …’

‘Swim them out,’ Titty heard Roger murmur to himself. ‘Or trot them, whichever’s quickest.’

Peggy had gone to the store under the elderberry bush where all the tinned things were kept in a hole in the ground for the sake of the coolness.

‘Nine tins,’ she said.

‘It’s no good keeping just one,’ said Roger. ‘There are sixteen sardines in each tin, so there’ll be a tin for each of us, and then two extra sardines each to finish off.’

‘All right,’ said Susan. ‘We’ll give you hot minced pemmican for supper and boiled potatoes. I’m awfully sorry about dinner.’

Nobody really minded. The charcoal mound, smoking like a gigantic pudding, was itself a kind of cooking. Nobody had had time to think of cooking dinners as well. People wandered round it, using spoons to eat sardines out of the tins, and licking up the last drops of the oil. It was no good thinking of making tea until the water in Titty’s well had settled down again. The quick dipping up of water for the damping of the turfs had made it very muddy.

‘I ought to have put a kettleful aside,’ said Susan. ‘We could have managed with the saucepan for watering the crust.’

‘We needed the kettle as well,’ said Dorothea.

‘And lots of miners die from hunger and thirst,’ said Titty. ‘It’s perfectly all right to go without tea for one day.’

‘Plenty of grog,’ said Roger.

‘We’ll share out what’s left of the milk,’ said Susan. ‘And somebody’ll have to go down for a fresh lot this evening.’

‘Let me,’ said Dorothea.

‘We’ll both go,’ said Titty.

Meanwhile the charcoal pudding could not be left for a moment. They had to let the moisture escape, and at the same time not to give the fire too much air. It was late in the afternoon before the smoke changed colour, and the greenish, tawny fumes drifting from the holes in the crust turned to the clear blue smoke that comes from dry wood.

‘It’s begun to cook,’ said Peggy.

‘Been cooking all the time,’ said Nancy. ‘Nothing to do now but to keep it well under. Let’s have some more water on the clods.’

‘Use the saucepan this time,’ said Susan. ‘And half a minute while I fill the kettle. We must have tea for supper. And the water is fairly clear again.’

Now and then somebody went to the Great Wall, or up the tree, to look out, but there was no sign of Squashy Hat either on the Topps or at Atkinson’s.

They sent off Homer with a cheerful message:

‘EVERYTHING GOING VERY WELL INDEED.’

It was not until evening that they had news of the enemy. Titty and Dorothea had gone down to Tyson’s with the milk-can, and had run on as far as the little bridge to cool their feet in what was left of the river. They were sitting on stones with their feet in the water when steps sounded on the road above them.

CHARCOAL PUDDING

‘Lurk! Lurk!’ whispered Dorothea.

But it was too late for lurking. And Squashy Hat, with his coat over his arm, came up the road and went by.

‘He’s been with Slater Bob all day,’ said Titty.

They hurried up the wood to the camp and told what they had seen.

‘Who cares?’ said Nancy. ‘The more they chatter the better. We’re well ahead of him now. Dick’s got a grand lot of stones for the blast furnace. And we’ll have charcoal tomorrow and an ingot the day after.’

Susan was making up for their sardine dinner by cooking a tremendous supper. Potatoes were simmering in the pot. Pemmican had been put through the mincing machine and was hotting in the frying-pan that was no longer needed for gold. And, in the middle of the old pitstead, the mound was quietly steaming. They put their hands on its earthy crust to feel the warmth coming through.

‘Who’s going to stop up all night with it?’ asked Roger after supper.

‘Not you,’ said Susan. ‘Aren’t you going to the gulch?’

‘No one’s going to the gulch,’ said John. ‘We’ll have to watch the fire all night. Squashy won’t try anything in the dark, and we’ll be on the look-out again as soon as it’s light.’

‘The able-seamen will have to go to bed at the proper time,’ said Susan.

‘What if I keep awake,’ said Roger.

But as dusk fell and darkness closed in on the camp, and owls called far below, and the churr of the nightjar sounded in the wood, Roger, like the other able-seamen, found his eyes closing. They went to bed, though not at once to sleep. For some time they lay in their tents, watching the glow of the camp fire. John and Nancy, Susan and Peggy, were taking turns with the charcoal-burning. The able-seamen lay there listening as now and then a clod of turf was thumped into place to stop a leak in the mound where the smoke was coming out. They slept, but even while asleep, knew that people were stirring in the camp. Titty half waked as the flash of a torch passed across her tent. She heard John whisper, ‘Where’s that thermos flask?’ She heard Nancy whisper back, ‘I’ve poured it out. Don’t step on the mug. What’s the time?’ The torch flashed again, and she heard John’s voice. … ‘Another hour before we wake Susan.’ Titty pulled her sleeping-bag over her ears. All was well.