PAGE FROM DICK’S POCKET-BOOK

29

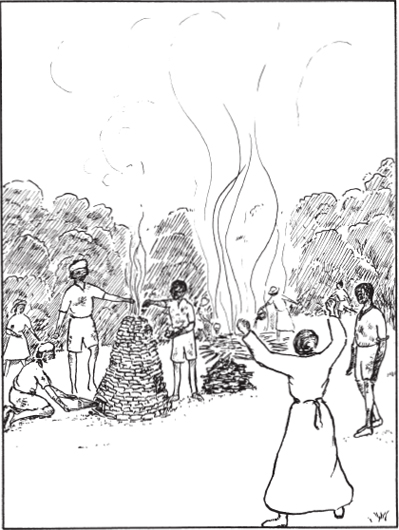

Blast Furnace

TITTY WOKE WITH the smell of wood smoke tickling her nostrils.

Was that Dorothea whispering at the door of her tent?

‘Don’t wake Nancy. Let Titty see them first. …’

‘Captains and mates, indeed!’ That was Roger’s voice.

‘Hullo, Dot!’ said Titty.

‘ ’Sh!’ said Dorothea and beckoned.

Titty crawled out into the camp. Charcoal-burning was still going on, but what had happened to the charcoal-burners? Dick and Roger, of all unlikely people, were sprinkling water and quietly patting down clods of earth on the smoking mound, and Dorothea pointed silently at the tent that was shared by Nancy and Peggy. There, with her head on her arm, lay Captain Nancy as fast asleep as anyone could be. Peggy was asleep, too, and so were John and Susan.

‘Lucky we woke,’ said Roger.

‘Dick heard the fire crackle,’ said Dorothea.

‘We were just in time,’ said Roger. ‘One small flame had licked its way through, but we soon stopped it. They’re all four sleeping like logs. It just shows. They ought to have let us sit up.’

‘Let’s put the kettle on,’ said Dorothea.

‘Let’s.’

‘What about dressing?’

‘Afterwards,’ said Titty. ‘Let them wake and find everything ready.’

But just then Nancy’s head moved with a sudden jerk. Her eyes opened. She began to yawn and, in the middle of her yawn, remembered.

‘Bobstays and jibbooms,’ she cried. ‘Hey! Susan. Your watch. Yours and Peggy’s.’ She tugged hard at one of Peggy’s feet, sleeping-bag and all. ‘Wake up. I’ve given you longer than I ought to have done. I must have been asleep the last few minutes.’

‘Ho, ho,’ laughed Roger.

‘What are you doing out of bed?’ said Nancy, blinking, and then, seeing Dorothea and Titty looking at her, and the bright sunlight, she laughed.

‘Barbecued billygoats,’ she exclaimed. ‘All asleep. Well done the able-seamen! You haven’t let the charcoal burn?’

‘It wanted to,’ said Dorothea.

John and Susan came sleepily out of their tents.

‘This is awful,’ said Nancy. ‘I ought to have routed Susan out hours ago. It was only just beginning to get light. … Look here, you’ll have to brew a lot of tea to keep us awake tonight. …’

‘Tonight?’ said Susan.

‘Blast furnace,’ said Nancy.

John stretched himself.

‘I’m off for the milk, anyway,’ he said, and a moment later was running down the path through the wood.

By the time the others had done as much washing as they could afford, and breakfast was ready, he came panting back again.

‘Your hair’s all wet,’ said Susan.

‘I just had an in and out while she was filling the milk-can,’ said John.

‘Lucky beast,’ said Roger.

‘One more day,’ said Nancy. ‘We must hang on dirty till tomorrow. Then we’ll take the ingot to Mother and have a swim in the lake. Some in the morning and some in the afternoon. We’ll have nothing more to do then except to keep watch and see that Squashy does no jumping. By the way, he isn’t on the prowl yet?’

‘Not yet,’ said Titty, who had already had a look out over the Topps.

‘When are we going to cut the pudding?’ said Roger, looking at the brown earth-covered mound from which little wisps of blue smoke trickled here and there.

‘Not till the last minute,’ said Nancy. ‘We’ll give it as long as we can. The furnace isn’t built yet. …’

‘The stones are all ready,’ said Dick.

‘Let’s have a look at that plan.’

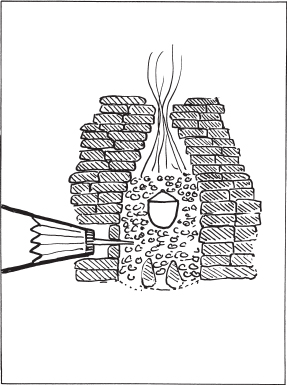

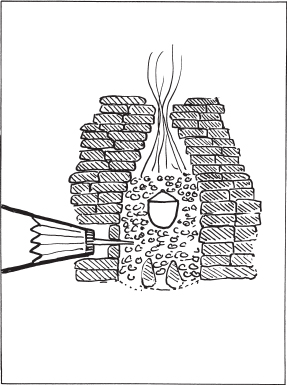

Dick pulled out his pocket-book and showed a drawing to Nancy.

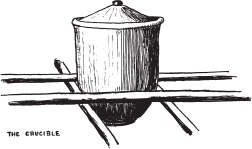

‘It’s a section really. Not awfully clear. There ought to be a plan as well. It’ll be round, not square. And I haven’t put in any sizes. There ought to be just room to have the crucible in the middle, with charcoal all round it, and the bellows coming in at the side and underneath the crucible.’

No one would have thought, to listen to Dick, that he was an able-seaman telling captains and mates just what they ought to do.

‘We can’t have a door to open and shut,’ he was saying. ‘But that won’t matter. We’ll have to build the crucible in at the last minute, and pour the bits of charcoal in at the top. I don’t see how we can manage a chimney, but with the bellows going all the time, we ought to get a good enough draught without, don’t you think?’

‘Can’t make head or tail of it, Professor,’ said Captain Nancy. ‘But I expect it’s all right.’ She passed the notebook to John.

‘How are you going to fix the bellows?’ asked John.

PAGE FROM DICK’S POCKET-BOOK

‘They won’t really have to be fixed, will they?’ said Dick. ‘Just a hole for the nose of the bellows. The rest of the bellows will all be outside. Of course it isn’t like the ones in the book, but the principle is the same.’

‘It looks the right shape,’ said Nancy.

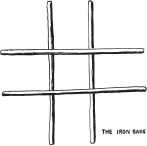

The building of the furnace began even before the breakfast things were washed up. It took a good deal longer than anyone had expected. In one way only was it different from the furnace of Dick’s sketch. They found that there was no good way of holding the crucible in the middle of the fire if they tried to balance it on stones. Crucibles are an awkward shape, like teacups with lids but no handles, and narrower at the bottom than at the top. What was wanted was iron bars, and Peggy remembered a bit of old railing rusting away behind the Tysons’ orchard wall. John galloped down the wood for the second time and brought it back. He filed three deep nicks in it with the file that was one of the most useful tools in the knife he had been given at Christmas. Then, bending the rusty rail this way and that, he broke it at the nicks into four pieces. These four iron bars were built into the furnace, two one way and two the other, so that the crucible would be held in the middle.

The furnace was only half done when Susan, who had opened the tinned tongue to save cooking (‘This is a special occasion,’ Peggy had said), called builders and charcoal-burners to their dinner. Even while they ate, people had to be getting up every other minute to pat a clod on the charcoal mound, and to do a little watering of places on the crust that looked too dry. The furnace-builders went back to their work after eating their share of the tongue, and put stones in place with one hand while holding plum cake with the other.

All was going well when Roger, who had taken his cake up the look-out tree, came slithering down in a hurry to say that Squashy Hat was on the Topps below Grey Screes and not very far from the gulch.

‘Oh, bother him,’ said Nancy. ‘Just when everybody’s busy.’

‘Dick and I could go,’ said Roger, who thought scouting was more important than fitting stones together and damping clods of earth.

‘Not the Professor, anyhow,’ said Nancy.

‘Let me go,’ said Dorothea. ‘Dick’s got to be here.’

‘There’d better be two of you,’ said John.

With a telescope and The Outlaw of the Broads, Roger and Dorothea went off together.

A couple of hours later, or maybe three, Dorothea, wide-eyed and white-faced, came breathlessly into camp.

‘What’s happened?’ cried Titty.

‘It’s the heat,’ cried Susan. ‘You’d better lie down.’

‘He tried to jump,’ said Dorothea.

John almost dropped the stone that he was fitting into place. Nancy started up.

‘Where is he now?’ she cried.

‘Gone,’ said Dorothea. ‘Roger’s snaking after him.’

‘What happened?’ said Titty.

‘We were in the gulch,’ said Dorothea, ‘and I was reading to Roger and all of a sudden I looked up and there he was, looking down over the edge.’

‘What did he say?’ asked Nancy.

‘He said, “I beg your pardon. I didn’t know anyone was here.”’

‘I bet he didn’t,’ said Nancy, ‘or he wouldn’t have been trying to jump. Gosh, it’s a good thing we didn’t show our gold to Slater Bob. What did you say?’

‘I didn’t say anything,’ said Dorothea. ‘And Roger didn’t either. And Squashy turned round and went away. He didn’t go back to his white spots. He went straight home.’

‘Foiled,’ said Titty. ‘I wish I’d been there.’ She looked at Nancy. Surely she would call the whole camp to arms and march down to Atkinson’s at once.

But Nancy did nothing of the sort. She looked at the charcoal mound, steaming all over because Peggy and Susan had just been sprinkling water on it. She looked at the furnace, now all but finished, a round stone pillar, hollow inside and tapering towards the top. She looked at the mouth of her tent where the cocoa tin, full to the brim with gold dust, was waiting to be emptied into the crucible.

‘Oh well,’ she said, ‘we can’t do everything at once. Making the ingot matters most of all, and we’re just ready to start. So long as he doesn’t actually jump. … Come on, Dick, where’s the crucible? We’d better have everything right before we open up the charcoal.’

Dick brought the crucible from his tent, where it had been put for safety’s sake, with so many charcoal-burners and miners stamping about the camp. Solemnly Nancy poured in the gold dust. Dick put the lid on.

‘What’ll it look like when we see it again?’ said Titty.

‘All scummy on the top,’ said Dick. ‘The pure gold’ll be underneath.’

‘Put it in your tent till we get the furnace lit. Now for the charcoal. Come on. All hands to cut the pudding. Slosh some more water on it first and get another lot of wet clods ready.’

‘And the fire-brooms,’ said John. He unstacked them and laid them handy in case of need.

‘Slosh some more water on it first,’ said Nancy again.

‘We’d better wet the ground all round it,’ said Susan.

The charcoal pile was no longer the round smooth pudding it had been. Here and there it had fallen in. Here and there it was swollen with clods of turf that had been plastered on it to stop a leak of smoke. Susan with the kettle, John with the saucepan, sprinkled water over the crust, and a great mass of steam poured up above the camp. Kettle and saucepan were filled again. Everybody had a damp clod ready.

‘Here goes,’ cried Nancy. She pulled a big clod of earth from the side of the pile and dumped it on the top. ‘That’s the way,’ she said, ‘it’ll be hottest in the middle, and the earth’ll keep it under.’

Unburnt ends of sticks showed. There was a sudden crackling inside the mound. Nancy pulled out a stick. The end of it was red hot and dripping sparks. She put it on the wet ground and dumped a clod on it. The stick broke into bits.

‘It’s charcoal all right,’ said Dick.

‘Three cheers,’ said Titty.

‘Three million,’ said Nancy, pulling out another bit. ‘Ouch! my fingers!’

The crackling inside grew louder, and smoke began to pour out and mingle with the steam.

‘Look out! It’ll flare up in a minute,’ said Susan.

‘It shan’t,’ said Nancy. ‘More water! Stand by. Don’t get too near. John and I’ll open it up.’

John and Nancy, working round the mound, pulled away clods of earth, dumped them in the middle, and hauled out stick after stick, letting each lie separately on the wetted ground. Peggy and Dick pressed wet clods on the red-hot ends. Titty and Dorothea raced backwards and forwards between the camp and the well, damping clods that had gone dry. Susan, with kettle and saucepan, poured water over any bits that looked like flaring. In a very few minutes there was nothing left of the charcoal mound but a small heap of violently steaming clods of earth.

‘It hasn’t all turned into charcoal,’ said Dick, looking at the blackened sticks lying all round it.

‘We’ve got a whacking good lot,’ said Nancy. ‘Giminy, I was afraid it was going to blaze up after all.’

‘It’s still red hot in the middle under that earth,’ said Susan.

‘We’ll want that,’ said John.

Roger came into the camp while they were still busy watering the charcoal to cool it and breaking it into bits small enough for use.

‘Why didn’t anybody come?’ he said. ‘Didn’t Dot tell you? Oh, I say, what pigs, opening the pudding without waiting for me.’

‘You’re just in time for the furnace,’ said Nancy. ‘What’s Squashy doing?’

‘Eating bread and cheese,’ said Roger. ‘And he’s got some bits of quartz on the table and some candles, and he’s blowpiping, just like Dick. I got a good view from behind the hollybush.’

‘Good,’ said Nancy. ‘That’ll keep him busy. Look here, John, what on earth can we use for a shovel?’

‘There’s only the frying-pan,’ said John.

‘Oh no,’ said Susan.

‘It’s the very thing,’ said Nancy.

A minute later John was clearing away the clods that covered what had once been the burning middle of the mound. Nancy scooped a frying-pan full of red-hot charcoal from under them and carried it carefully across to the furnace. Some handfuls of dry twigs had already been put in there to give the fire a start. Using her knife, Nancy worked the red-hot embers from the frying-pan through the bars. The twigs blazed up beneath them.

‘Quick. More charcoal,’ she cried. ‘Come on, Dick. Shove in the crucible.’

Handfuls of black charcoal were put in. Dick brought the precious crucible and, regardless of the heat, balanced it in the middle of the bars as gently as if it had been an egg.

‘May I start the bellows?’ said Roger.

‘One second. We’ve got to get the crucible walled in first. And then fill up with charcoal from the top.’

John and Nancy worked feverishly together, blocking up the hole through which the crucible had been put in. First the big stone that was lying ready. Then small ones. Then earth. The others dropped bits of black charcoal down the chimney. Dick leaned over and looked in but could see nothing for bitter smoke.

‘The fuller the better,’ he said. ‘We’ve got to keep it full and red hot.’

‘It’ll go out in a minute,’ said Susan.

‘Go ahead with the bellows, Roger,’ said Nancy. ‘And keep it up while we get all the holes properly caulked. That’s right, Titty. Shove a bit of earth in everywhere you see smoke coming out between the stones.’

Roger had already poked the nose of the bellows through the hole that had been left for it at the bottom of the furnace. He began pumping. ‘Wough. … Wough. … Wough.’

‘It makes the right sort of noise,’ said Titty, as Roger quickened the time of his blowing and the hiss of the air into the fire turned to a regular snoring roar.

‘How much more charcoal must we put in, Dick?’ asked Dorothea, wiping her hot face with charcoal-covered hands. Peggy, seeing her, suddenly burst into laughter. But Dorothea broke into laughter also, for Peggy had wiped her own face a moment before.

‘Oh well,’ said Susan, looking at both of them, ‘it can’t be helped.’

‘Look here,’ said Roger. ‘Somebody else’s turn.’

These bellows were worse than the crushing mill. They were so near the ground that even Roger had to crouch to be able to work them.

Nancy took over. She, too, started at a racing stroke, but slowed down after the first minute. She tried one way and then another of squatting and stooping at the side of the furnace, so as to be able to work the bellows without breaking her back at the same time.

‘Giminy,’ she said, ‘this is lots worse than the charcoal-burning. And we’ve got to keep it up all night.’

‘All night?’ said Titty.

‘Proper blast furnaces never go out,’ said Nancy, who was all the time working the bellows. ‘And we’ve got to get it boiling and keep it boiling, so that all the gold will go to the bottom and all the rubbish come up to the top. Twenty-four hours at least, Dick says.’

‘Not you four,’ said Susan. ‘You’ll go to bed after supper as usual. Last night was bad enough. I don’t believe any of you slept right through. Tonight all able-seamen go to bed at half-past eight. …’

‘You have a turn,’ panted Nancy, and John took her place.

‘Don’t start too fast,’ said Nancy. ‘It’s much worse than you’d think.’

This John found for himself, and Peggy after him. Keeping the bellows going steadily was no sort of a joke, and none of the captains and mates seemed at all unwilling when Titty, Dick and Dorothea asked to be allowed to work the bellows in their turn.

‘Jolly hard work, isn’t it?’ said Roger, watching them with his hands in his pockets.

‘Twenty-four hours of it,’ said Nancy. ‘Suffering alligators! What time is it now?’

‘Oh,’ said Susan. ‘I ought to have been thinking about supper. It’ll have to be only potted meat. This is an awful day. …’

‘And the pigeon’s not gone,’ said Dorothea.

‘Giminy,’ said Nancy.

‘Sappho’s turn,’ said Titty.

‘Better send Sophocles,’ said Nancy. ‘It’s late already and you can’t depend on Sappho. We don’t want the natives charging in tonight. And they will if the pigeon doesn’t turn up. Tomorrow it won’t matter. We’ll be there ourselves. We’ll take the ingot down to show Mother.’

Nancy scrawled the message:

‘TRIUMPH IN SIGHT. LOVE FROM ALL S.A.D.M.C.’

‘That’ll puzzle her,’ she said. She took a bit of charcoal and scratched a skull on the back of the paper. … ‘Just to let her know there’s nothing to worry about.’

‘Dot’s turn to let fly,’ said Titty.

‘Wough. … Wough. … Wough.’ The bellows never stopped for a moment. As fast as one of them tired, another took over. Charcoal was poured in at the top of the furnace. Susan was busy with the supper. Everybody was startled by a sudden native voice.

‘Whatever are you doing?’

Mrs Tyson was standing in the camp, looking at the steaming remains of the charcoal mound, and at the blast furnace. Anybody could see she was both frightened and angry.

‘You’ll have the wood on fire for sure. And after all I tell you. With the smoke blowing I thought it was alight already. Nay, I can’t have this. There’s nowt to stop it if a spark catches hold … Miss Nancy! MISS NANCY!’

The miners blinked at her with eyes reddened by the smoke. Hands, faces, clothes were black with charcoal.

‘It’s quite safe,’ said Nancy. ‘It wasn’t smoke you saw. Only steam. Go on, Peggy. Don’t stop blowing.’

‘Wough. … Wough. … Wough.’ The regular noise of the bellows, that had slackened for a moment, went on.

Dick dropped another handful of charcoal in at the top.

‘Nay, but stop it!’ said Mrs Tyson. ‘If you’ve owt to cook, you can come down and use the kitchen range.’

‘We can’t stop now,’ said Nancy.

John and Susan looked at each other.

‘We’re taking great care,’ said John.

‘Care!’ snorted Mrs Tyson. ‘And making fires like yon. They’ve had fires and enough on yon side of the lake, where they’ve plenty folk to put them out. But here, with none to help us, we’ll be burnt like a handful of tow. Put it out, Miss Nancy. I can’t do with you here, and I must tell Mrs Blackett. You’ll go home to Beckfoot tomorrow, and if you don’t like it you mun lump it. Put it out, Miss Nancy. Put it out and no more said.’

‘We’ll be done by tomorrow,’ said Nancy.

‘You’ll be home tomorrow and away out of here,’ said Mrs Tyson. ‘Have you all gone daft?’

And she went off down the wood, muttering to herself.

‘I say,’ said John, ‘what can we do?’

‘Nothing,’ said Nancy. ‘Keep it up, Peg. … Oh, all right. I’ll take a turn. … We’ll have the ingot made by tomorrow. She’ll calm down when she sees nothing’s happened. It’s too late for her to go and talk to Mother tonight. …’

MRS TYSON VISITS THE CAMP

‘If only she was like Mrs Dixon,’ said Dorothea.

‘Mr Dixon would be helping if he was here,’ said Dick.

‘It’s no good talking about it,’ said Nancy. ‘We can’t throw it all up now, just because Mrs Tyson’s in a stew.’

Titty and Roger looked at Susan and John. What would Mother say to such handling of a difficulty with the natives? But it was no good saying anything to Nancy. They were in for it now. Mrs Tyson was gone. Susan with a sigh went on spreading potted meat, looking rather native herself. John beat out a few red embers left from the charcoal-burning, and put another double handful of charcoal into the top of the furnace.

Work never stopped for a moment. People ate their suppers in turn, when they could be spared. There was very little talking … only the noise of the flames inside the furnace, and the ‘Wough, wough, wough’ of the bellows.

‘You’ll simply have to let us stay up tonight,’ said Roger, who was watching Susan work the bellows while he munched an apple to round off his supper.

Susan said nothing, but looked more native than ever.

‘Eight’s better than four,’ said Roger. ‘And even Captain Nancy snored this morning.’

‘Snored!’ said Captain Nancy. ‘Shiver my timbers!’ But she looked at Susan and then at John and added, ‘The more hands the better all the same.’

‘It can’t be helped,’ said John. ‘Somebody’ll have to keep blowing all the time. And somebody’ll have to keep on feeding in the charcoal.’

And gradually even Susan’s stern intentions weakened. Facts were too strong. The whole result of all their mining was in the crucible inside the grey stone furnace. At all costs the draught had to be kept up and the fire fed. And this business of pumping away at the bellows tired anybody out in no time. The more there were at it the better for everybody, to let the turns be as short as might be and the rests between the turns as long. Finally, Dick was the only one who really knew about blast furnaces and crucibles. If Dick was to be awake, and they could not do without him, how could the others be expected to go to sleep? In the end the thing just happened. Supper was never washed up. The kettle was boiled again and again. People ate hunks of chocolate and bread and butter when they felt hungry. Parched throats were wetted with hot weak tea at all sorts of hours. When one miner was tired of working the bellows another took over. Miners not busy feeding the furnace lay by the camp fire, or squatted on their heels looking with hot eyes into the flames. The night darkened about the camp. The fire gave just enough light to make the sky seem black as pitch. Talk died away. Work went on. With eight of them to take their turns there was time for each of them to get a little rested, but not to settle down to sleep. Before the sky began to pale overhead, and trees showed grey against it, they felt they had been tending blast furnaces all their lives. Charcoal-smeared faces made no one laugh, for all alike were grimed.