THE FLAMES ROARED PAST OUTSIDE

32

In The Gulch

IN THE GULCH, once Dick had hurried away with his pinch of dust in his handkerchief, nothing seemed worth doing any more. While he was there, with his talk of aqua regia and tests to prove that gold was gold, everybody had felt that there was still hope. Now that he was gone, it was as if he had taken the hope with him. They could think only of the broken crucible and the worthless ashes among the ruins of the blast furnace. ‘Triumph in sight’ had been the last message sent to Beckfoot. Today they were to have carried home the ingot. And there was no ingot. All their work had gone for nothing. Even Nancy felt it was hardly worth while going on with the quarrying and crushing until the professor came back.

They had taken some splendid lumps of quartz seamed all over with glinting yellow out into the sunshine. It looked good enough, but was it?

‘I wonder if it is or it isn’t?’ said John, turning over the best bits.

And Nancy did not feel like shivering timbers. She said, flatly, ‘I don’t know.’ A moment later she added, ‘It’s our fault, really, not Dick’s. We ought to have sweated up the chemistry ourselves.’

‘Dick nearly always is right,’ said Peggy. ‘About things like that.’

‘Not this time,’ said Susan.

‘Even if he is,’ said John, ‘we’re not going to have time to make an ingot. …’

‘We can’t go on staying if Mrs Tyson wants us to go,’ said Susan.

They went dismally back into the mine.

In there, in the comfortable darkness, that was broken only by the dim light of the hurricane lantern hanging from the iron peg, all four miners felt more and more sleepy. After all, it was two days since anybody had had a proper night’s rest. No one was in a hurry to get back to work. They did not feel even like talking. When somebody said something it just dropped dead like a stone.

‘Dick can’t be back till pretty late,’ said Susan. The others heard her, but that was all.

‘How long does it take to come from South America?’ said John.

‘Not long in a fast ship,’ said Nancy dully. ‘But ages in a tramp.’ And John was too tired to ask her what was the use of an answer like that.

‘Peggy, you’re falling asleep,’ said Nancy, a few minutes later.

‘Well, why not?’ Peggy yawned, leaning back against the wall. Nancy said nothing. She found her own eyes closing.

It was a long time before anybody spoke again.

Peggy opened her eyes and blinked hard. Who was asleep? Not she. And then she smiled at seeing that Nancy’s eyes were shut. John’s head had fallen forward, and Susan’s was all on one side. The lantern burned dimly on the wall of rock. What time of day was it? Perhaps no need to wake them yet. Peggy stood up and went, on tiptoe, to the mouth of the cave. … What on earth was happening? What were those crackling noises? And the sky was full of smoke. For one moment she could not believe it. Then she knew. It had happened, the thing people had been dreading all the summer. This was the end of everything.

She darted back into the mine and pulled Nancy by the arm, and John.

‘Wake up,’ she cried. ‘Nancy! John! Susan! Quick! Wake up! The fell’s on fire.’

‘What’s the matter?’ said Nancy, more than half asleep.

‘Fire,’ shouted Peggy. ‘FIRE!’

‘Don’t be a galoot,’ yawned Nancy.

‘It’s not time to get up yet,’ said John, stretching an arm.

‘FIRE,’ yelled Peggy. ‘It’s a big one. Oh, Susan! Do wake up!’

Nancy staggered to her feet and went sleepily out of the mine, steadying herself with her hands against the rocky walls. The others, rubbing their eyes and yawning, were close behind her. They were not out of the tunnel before they heard that queer running crackle of fire in short grass and smelt the smoke in the air.

‘Giminy,’ said Nancy. ‘She’s right. Some wretched idiot’s set the fell on fire. … I say, and all the fire-brooms are in the camp. …’

‘What about Titty and Roger?’ cried Susan.

‘And Dorothea,’ said John.

They came out into the gulch. Thick clouds of smoke were rolling high overhead. The sun showed through them like a red-hot penny, disappearing as the smoke thickened and showing again as it thinned.

They were just bolting across the gulch when they saw that they were not alone.

Only a few yards from the secret entry to their mine a man was lying full length on the ground, pillowed on a clump of heather. His feet were what they noticed first, large feet in heavily nailed climbing-boots. His face was hidden. He had been using a map, and had spread it over his face like a tent to keep off the sun. He was lying on his back, and his left hand rested on the pile of good lumps of quartz that John had brought out from the mine that morning. The sight of that hand, half-closed over the quartz, turned it to gold again, at least for Nancy.

‘It’s Squashy Hat,’ she said, almost in a whisper. ‘And he’s got his paw on our gold. …’

‘Gosh!’ said Peggy.

‘Come on,’ said John. ‘We’ve got to get across. …’

Susan was already climbing the other side of the gulch. The fell was on fire, and for gold and Squashy Hat she had not a thought to spare. … Roger and Titty, left alone. …

‘He’s asleep,’ said Peggy.

‘Serve him right if we let him roast,’ said Nancy, but she could hardly do that. Instead she poked him with a foot.

‘Wake up,’ she said. ‘FIRE! Come on, Peggy!’ and leaving Squashy Hat to do what he thought best, she and Peggy raced after the others.

Bracken flared in their faces and a cloud of thick smoke rolled down to meet them over the edge of the gulch. They dropped back choking.

‘It’s between us and the camp,’ shouted John. ‘We’ll have to get round.’

‘It’ll be in the gulch in another minute,’ said Nancy.

‘Prairie fire,’ said a quiet voice below them. ‘No time to be lost. We’ve got to run for it. All right if we get away up on the Screes.’

They looked down. Squashy Hat, whose guilty conscience had always made him bolt at the sight of them, had a voice that was somehow steadying.

‘We can’t,’ said Nancy.

‘We’ve got to get back to the camp,’ said Susan, desperately looking this way and that at the smoke that seemed to be coming from all sides at once.

Squashy Hat ran up the steep slope, and stood there in the smoke.

‘You’re right,’ he said, ‘we can’t get to the Screes. But we’ve a chance yet,’ he went on, in that same steadying voice. ‘There’s a bit of a gap to the norrard.’

They raced together, the four prospectors and the rival they had caught with a clutching hand actually resting on their gold. They raced along the bottom of the gulch. They came up out of the gulch at its northern end just in time to see the flames meet again beyond them. The gulch was an island in the middle of the fire.

The island was growing quickly smaller as the fire came licking through the stones from grass patch to grass patch, blazing noisily through heather and bracken.

Squashy Hat looked anxiously round. They could see he was wondering what best to do. He spoke again, rather gravely. ‘The whole place’ll be ablaze in another two minutes,’ he said. ‘Our best chance will be among those stones. …’

‘But Titty and Roger. …’ Susan stared hopelessly into the smoke.

‘We must get back,’ shouted Nancy. ‘Come on, you!’

They ran back. Squashy Hat stopped on a bit of stony ground where there was not much grass to feed the fire.

‘What are you waiting for?’ shouted Nancy. He might be a rival, a robber and jumper of claims, but she could not leave him to burn.

Squashy Hat was taking off his coat. ‘You’d better get your heads under this,’ he was saying. ‘But I’m afraid we’re fairly trapped.’

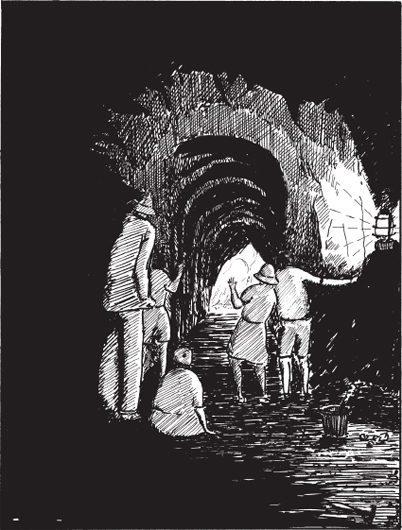

‘Come on,’ said Nancy. ‘Get back into the mine. …’

‘What mine?’ said Squashy Hat.

‘Ours,’ said Nancy. And even in that dreadful moment a note of triumph came into her voice. He had not found it. ‘Our mine,’ she said again. ‘We’ll let you in, but no jumping!’

‘What do you mean?’ said Squashy Hat.

There was a sudden wide leaping flame and a roar as the fire caught the dry grass at the southern end of the gulch. There were sparks flying red in the smoke above their heads. On the further side of the gulch a patch of bracken blazed up like a bundle of fireworks.

‘Look here,’ said John. ‘I’ve got to get across to the camp.’

‘You can’t,’ said Nancy. ‘Get into the mine. It’s the only hope. Your getting burnt won’t help anybody. Come on. Get in, Peggy. Quick.’

Peggy was waiting by the mouth of the old working. She stooped and was gone.

‘Well, I never saw that,’ said Squashy Hat.

‘Hurry up, Susan!’

‘Go in yourself!’ said John.

‘Of all the turnipheads!’ said Nancy, and bolted in after Susan.

The heather flared close above them.

‘After you,’ said Squashy Hat.

‘It’s not your mine,’ said John.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Squashy Hat. He stooped and bent his long legs and worked his way through the tunnel with John close behind him.

They were not a moment too soon. They were hardly inside the mine, where the lantern still burnt and lit their startled faces, before thick smoke closed the entry.

‘We’ve just got to wait till it’s over,’ said Nancy, and sat down comfortably on the floor of the cave, to show Peggy that there was really nothing to worry about. John and Susan stared at her. ‘Nothing to worry about!’ And then, suddenly, there was a glow of red in the mouth of the mine. Then leaping flames as the fire roared past. Then, again, nothing but smoke.

‘I’m very much obliged to you,’ said Squashy Hat gravely. ‘I shouldn’t have stood much of a chance outside.’

‘You oughtn’t to have been there,’ said Nancy. ‘Didn’t you see our notice? It’ll be burnt now, but you must have seen it.’

‘Well, yes, I did,’ said Squashy Hat. ‘But I was busy looking for something, and I didn’t think any of you were about. …’

Nancy jumped to her feet. ‘All the worse,’ she said. ‘What were you looking for?’

‘It wouldn’t interest you,’ said Squashy Hat mildly. ‘Not really. Mining, you know. It’s my job. I was following up a vein. …’

‘What?’ Nancy’s indignation was almost more than she could bear.

‘Funny I never noticed this,’ he said. ‘I was thinking there might be something of the sort.’

‘It’s ours,’ said Nancy. ‘Couldn’t you read that notice?’

‘Something about some game,’ said Squashy Hat. ‘Something about riding or leaping wasn’t it? And a picture of a death’s head?’

‘Telling people not to jump claims,’ said Nancy. ‘You must have known. …’

But there was no more on that subject, for the noise of the fire was further away, and the smoke was clearing outside, and John and Susan were already starting out of the mine.

‘Take care,’ said Squashy Hat suddenly. ‘Give it time to cool underfoot.’

‘We’ve got to go,’ said John.

‘The others won’t know what to do,’ said Susan, and followed John.

‘What others?’ said Squashy Hat.

‘Three more of us,’ said Peggy. ‘Younger than us. In the camp at the top of the wood.’

Squashy Hat hurried after John and Susan. Nancy and Peggy hurried after Squashy Hat.

Even in the mine the air had been bitter with smoke. It was far worse outside. The fire was raging at the northern end of the gulch. It had swept through, burning everything but earth and rock. Clumps of heather were still flickering like torches dropped and forgotten by a procession on the march. The ground smoked under their feet. They burned their hands when they touched the rocks in scrambling up the steep side of the little valley. The fire had poured northwards over the Topps, which were black and smoking as far as they could see. Stretches of grass and bracken were still blazing between the gulch and Tyson’s wood. A high curtain of smoke hid the Great Wall and the trees beyond it, and along the foot of that curtain they could see little spirts of flame.

‘The wood itself may be on fire,’ said John, as he dashed forward with the ashes smoking about his feet.

‘They may be asleep in their tents,’ cried Susan.

‘Oh, no. … No. …’ shouted Nancy fiercely. ‘They aren’t utter galoots. …’

‘Not that way,’ shouted Squashy Hat. ‘You follow me. We’ve got to cut round that lot.’

His long arms were working like a windmill. He was leaping rocks that came in his way, dodging others he could not leap.

The four prospectors raced after their rival. They were not prospectors now. There was only one thought in all their minds as they skirted a stretch of blazing bracken and ran splashing through the hot ash, towards that wall of smoke. Somewhere behind that smoke was the camp.

THE FLAMES ROARED PAST OUTSIDE

‘If only they’ve had the sense to run away,’ panted Susan.

‘They’ll be all right,’ said Nancy, and choked with the fine ash in her mouth.

And then a puff of wind blew the smoke towards them. It lifted and for a moment cleared. Dimly beneath it they saw figures, small, dim, beating frantically at the ground.

‘Titty. … Dorothea. …’

‘There’s old Roger,’ shouted Nancy.

The smoke rolled down again thicker than before. But Squashy Hat had seen them, too. A moment later, racing straight for them, he, too, had disappeared.

‘Come on,’ John shouted over his shoulder. ‘They’re all right. This way!’