33

At Beckfoot

DICK BRAKED CAREFULLY, feeling first in one pocket and then in another to make sure that he had forgotten nothing. Blowpipe in handkerchief pocket with fountain pen. Phillips on Metals bumping in the knapsack on his back … no forgetting that. Lumps of quartz in one side pocket of his shorts. … Charcoal in paper in the other. … Pinch of precious dust in handkerchief. … Notebook with knife in hip pocket. … Bump. … Bump. His hand flew back to the jerking handlebar. Nearly off that time. He must not let himself think of anything but the steering of his dromedary. … Oh. … The dromedary skidded on the loose stones as the path suddenly turned a corner, and Dick got a foot to the ground only just in time to save himself.

He pushed off again and found his pedal. … Woa. … Don’t let the beast get going too fast. And don’t go jamming the brake on so that the wheels lock. … If only they had not put all the gold dust into the furnace. Quantity did not count. Nancy had said at the beginning that all that mattered was to prove that the gold was there. … Just a blob. … One golden blob would be enough. With the blowpipe and a proper spirit-lamp he ought to be able to manage that, try it with aqua regia to make sure, and then everything would be all right after all. Meanwhile the dromedary was jolting him almost to pieces as it slipped and jumped and jibbed and skidded and bucked over the loose stones in the old path down the wood. You never would have thought it was possible to get so hot going downhill. He came at last to the bottom, bumped across the cobbles of the farmyard, was glad not to see Mrs Tyson, crossed the bridge and came out on the valley road which, dusty as it was, was much better travelling for dromedaries. He pedalled away down the valley as fast as anybody could on a girl’s bicycle at least two sizes too big for him.

Beckfoot looked quite different. Paperers and painters and plasterers were gone. The carpets were down even on the stairs, and chairs and tables were all back in their places. He met Mrs Blackett in the hall.

‘Hullo, Dick,’ she said. ‘You’re just in time for lunch. Have you come to have a look at your pigeon-bell? I’ve just pushed the slide across to set it. It’s been working beautifully since you put it right the other day. Nearly deafens us with every pigeon. …’

‘There won’t be one today,’ said Dick, ‘because of me coming.’

‘I’m glad one of you has come. I’ve got news for all of you. Your father and mother are going to be at Dixon’s Farm the day after tomorrow. And Mrs Walker and Bridget are coming here for a day or two before moving across to Holly Howe. And then I suppose you’ll all be shifting camp to Wild Cat Island. My brother’s in England, too. This postcard came today with a London postmark. A picture of the Tower Bridge and not a word on it except “Give my love to Timothy”.’

‘But has Timothy come?’

‘No, he hasn’t,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘But what can I do about it? I don’t even know my silly brother’s address in town. Just like him. …’

‘Timothy must have died on the voyage,’ said Dick. ‘Not enough green food probably. Captain Flint’ll be dreadfully disappointed.’

‘Well I do wish he’d stop dashing off here and there about the world and sending home heaven knows what. It was bad enough with monkeys and parrots. But when it comes to dead lizards …’

‘Armadillos aren’t exactly lizards,’ said Dick.

‘Well, crocodiles,’ said Mrs Blackett. Dick did not put her right. Zoology meant nothing to some people.

‘Can I work in Captain Flint’s room?’ said Dick. ‘It’s something I’ve got to do before he comes back. …’

‘After lunch,’ said Mrs Blackett. ‘Come along, we’ll find an extra plate for you.’

And Dick found himself somehow in the dining room eating cold beef and salad. Dreadful, with the test still to be made and the acids waiting in their bottles in the little room on the other side of the hall. But it could not be helped, and Dick found himself very hungry, though two or three times he nearly fell asleep. Although, at Dorothea’s suggestion, he had done his best to clear the charcoal off his face, there must have been some smudges left. ‘I expect you’ll all be glad to get back from the desert and to have proper baths again,’ said Mrs Blackett. Dick told her something about the charcoal-burning and the smelting, but not very much. She enquired after the bellows, and he said they had been very useful and that Nancy wanted her old purse to get a bit of leather for a patch, and some tacks. … And he pulled out his notebook to make sure. ‘In drawer in hall,’ he read. Mrs Blackett laughed. ‘I suppose I ought to be glad the bellows survive at all,’ she said, and then she kept asking him how he liked the new paper, and a lot of questions like that which were hard to answer when he was so sleepy and could think only of gold and aqua regia.

Luncheon was over at last and she took him to the study door.

‘Here you are,’ she said. ‘You’ll find me somewhere about if there’s anything you want. It seems to me you’ll be glad to get back to school, Nancy’s kept you so hard at work these holidays. What is it this time? Encyclopaedia?’

‘Only partly,’ said Dick. ‘It’s …’ But he had no time to explain. Mrs Blackett was too busy to listen, and was talking to Cook in the hall even before she had shut the study door.

Dick knew exactly what he wanted and where it was. Lucky that in the general redecoration of Beckfoot, Captain Flint’s study had been left alone. The glass door of the instrument cupboard was not locked. There was the little spirit-lamp he had seen, and, yes, there was some spirit in the blue bottle labelled ‘Meth’. He filled the little lamp and left it for the wick to soak, while he had just one more look at the article on gold in the Encyclopaedia. Then, sitting at the table, he lit the lamp, opened his handkerchief with the gold dust, took out his blowpipe, put a pinch of dust in a hole in a bit of charcoal, and began. The spirit-lamp was much better than a candle, and he was able to keep a fine jet of flame playing on the dust. But everything happened just as it had in the camp. The dust seemed to gather together into a red-hot blob just as he had hoped, and then, when he let it cool, the blob turned dark and crumbled into powder when he pressed it with a knife. He tried again. No better. Bother the blob. He would have to make the acid test on the gold dust itself. Why not? If it was going to work, it would be easy to see if the gold disappeared.

In the cupboard was a stand with a row of test-tubes. Dick brought it to the table and chose the smallest. He put some of the gold dust on a scrap of paper and tilted it into the tube. Then he put the test-tube back in the stand and set about making the aqua regia. ‘Nitric acid and hydrochloric acid. … Equal parts.’ It was not too easy to stir the glass stopper of the nitric acid bottle, and Dick was very much afraid of letting even a drop of the acid spirt out on Captain Flint’s table. He managed in the end by wrapping his handkerchief round the stopper and so getting a better grip on it. He did not take the stopper right out, but, even so, the choking fumes of the acid seemed to fill the room. The bottle with hydrochloric acid opened easier. He poured a little into a test-tube, closed the bottle and put it aside. Then, doing his best not to breathe the fumes, he poured in the same amount of nitric acid. There. The aqua regia was ready. Dick might have been alone in a world empty except for two test-tubes, two bottles, Phillips on Metals and the Encyclopaedia Britannica. He did not hear the sudden stir in the house. … The opening and shutting of doors might have been in some other house a million miles away. Voices in the hall might just as well have been in Jupiter or Mars. Dick heard nothing, saw nothing, thought of nothing but the test that was at last to be made.

‘Gold dissolves in aqua regia.’

That was the sentence in his mind. Well, would it? With a hand that trembled in spite of all he could do to keep it steady, he poured the aqua regia into the test-tube at the bottom of which lay that little pinch of glittering, golden dust.

It was as if the liquid suddenly boiled. Bubbles poured from the dust, which rose and fell in the acid as if it were trying to get away. The tube was hot to the touch. For a moment he was afraid it would crack and scatter acid in all directions. It was not boiling quite so hard. Sediment was settling at the bottom of the test-tube. The liquid above it was transparent, yellowish. Dick held it up to the light. Every glittering particle was gone, leaving only a dull sediment. The metallic dust had dissolved. A slow, happy grin spread over Dick’s face. Gold after all.

And then, slowly, he came to know that the door of the study was open and that Captain Flint was standing in the doorway, Captain Flint, with a face burnt redder than ever, smiling at him and polishing a bald head with a green silk handkerchief. Captain Flint threw a felt hat on the table, brought a suitcase bright with steamer labels in from the hall, closed the door behind him and laughed.

‘Well, Professor,’ he said. ‘What is it this time? It was astronomy when I found you in the cabin of the old houseboat. What’s this? Chemistry?’

‘Gold,’ said Dick.

‘Gold?’ said Captain Flint. ‘Don’t you go and get interested in the wretched stuff. Gold or silver. I’ve sworn off both of them. Had quite enough of wasting time. … Hullo. What have you got in that test-tube?’

‘Aqua regia,’ said Dick. ‘And gold dust. And it’s gone all right.’

‘What?’ said Captain Flint. ‘What’s gone?’

‘Dissolved,’ said Dick. ‘Gold in the aqua regia. I was just a bit afraid it might not be gold, after all.’

‘But, my dear chap,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Aqua regia will dissolve almost anything. The point about gold is that it won’t dissolve in anything else. …’

Dick’s face fell.

‘I’ve messed it again,’ he said. ‘I ought to have tried with the nitric and hydrochloric separately first. I say, may I use a drop more of each of them?’

‘Go ahead,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Got any more gold dust?’

‘Only a little,’ said Dick. ‘Properly crushed and panned.’

Captain Flint rubbed his little finger in the dust still waiting on Dick’s handkerchief. He pulled out a little magnifying-glass and held it close above those glittering particles.

‘But this,’ he said at last, ‘looks to me like perfectly good copper pyrites. You haven’t been crushing up some of my specimens, have you? Where did you get it?’

‘High Topps,’ said Dick. ‘We had a tremendous lot ready panned, but there was an accident with our blast furnace. …’

‘Your what?’

‘Blast furnace,’ said Dick, ‘and we lost it all mixed up with the ashes, and the crucible got broken. … Oh, I say, it was your crucible, you know. … We borrowed it. … There was only one that was big enough. Nancy said you wouldn’t mind. You see, the gold was for you. …’

‘For me? … But what is all this? I couldn’t make head or tail out of what my sister’s been telling me.’

‘She didn’t know, really,’ said Dick. ‘At least not everything.’

Captain Flint had hauled up a chair and was sitting at the table. ‘Let’s have a look at that test-tube,’ he said. ‘What did you say was in it? Nitric acid, hydrochloric and some of this dust? … Just look along that shelf and fetch the bottle marked “Ammonia”. … Good man. … Out with the cork. Let’s have it. … Now. …’

Drop by drop he let the ammonia trickle down the tube. There was some more fizzing. The clear liquid clouded thickly and then turned a brilliant blue.

‘There you are,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Copper. … What on earth made you think it was gold?’

And Dick told of the plan and of Slater Bob’s story.

Captain Flint interrupted. ‘And the young man went to the war, and so his secret was lost. Why, I heard that story when I was a boy. Thirty years ago it was the South African war, and before that it was the Zulu or the Crimean, and I dare say a hundred years ago Slater Bob’s grandfather was talking of the gold some young fellow would have mined if only he hadn’t had to go off to fight Napoleon. But where did you get the copper? Nancy couldn’t have had the slightest idea. …’

Dick tried to explain, but he had hardly told Captain Flint about the old working in the gulch and the quartz before Captain Flint jumped up.

‘Quartz. … Copper. … In one of the old workings. Got any here?’

Dick pulled a lump out of his pocket.

Captain Flint weighed it in his hand, looked at it closely, scratched with his knife at what Dick had thought was gold.

‘Soft as butter,’ he said eagerly. ‘And is there much like that?’

‘Lots,’ said Dick. ‘Susan wouldn’t let us do any blasting. We had nothing to get it out with but hammers and a chisel. And I was sure it was gold. The others’ll be dreadfully disappointed.’

‘Do you know that’s the richest copper ore I’ve ever seen?’ said Captain Flint. ‘If the rest’s up to sample we’re going to make our fortunes. … Gold. … Who wants it if there’s enough of this about? I was sure it was up there somewhere. Now if only Timothy hadn’t disappeared. …’

Dick suddenly remembered that, if Nancy and the rest were to be disappointed about the gold, Captain Flint also had a dreadful misfortune to face.

‘He’s never arrived,’ he said. ‘And the worst of it is they would never know it was waste to bury him at sea instead of bringing him home to be stuffed for a museum.’

‘What do you mean?’ said Captain Flint.

‘We had everything ready for him,’ said Dick. ‘We began as soon as your telegram came saying he was to be put in this room.’

Captain Flint’s eyes, following Dick’s, came to rest on the tropical grove, and the packing-case sleeping-hutch, with its ‘Welcome Home’ and its floral decorations. He looked closer and burst into a roar of laughter.

‘Well, it’s no good saying I wrote to explain. … I found the letter unposted in my pocket aboard ship. Poor old Timothy!’ He slapped his knee and laughed again.

‘Did you give him to a steward to look after?’

‘But what did you think he was?’

‘Armadillo,’ said Dick, and gave his reasons.

‘Skin not thick enough,’ laughed Captain Flint. ‘Well, we won’t disturb the sleeping arrangements you’ve made for him. Hay? … Sawdust? … He ought to be very comfortable indeed. … Eh! Bless my soul! What’s that? …’

Even Dick was startled by the suddenness of the noise.

‘Br!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!!!! …’

There could be no possible doubt that the pigeons’ bell was in splendid working order.

Captain Flint, old traveller as he was, admitted afterwards that he had jumped half out of his skin.

‘Br!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!!!!! …’

Bell and tea-tray, with the kitchen passage as a sounding-box, made a noise almost deafening, urgent, threatening, like an alarm clock close to a sleeper’s head.

‘What on earth’s that?’

‘Br!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!!!! …’

‘It’s one of the pigeons,’ said Dick. ‘Funny their sending one today with me here. …’

‘Br!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!r!!!!! …’

‘Can’t we stop it?’ said Captain Flint, with his hands to his ears.

Dick had already heard Mrs Blackett running downstairs. He was out in the hall in a moment.

‘I’ll stop it,’ he said. ‘It’ll only be a message for me, something Nancy thought of after I’d started.’ Mrs Blackett went upstairs again to get his room ready for Captain Flint.

Dick ran out of the back door, across the yard and up the steps to the pigeon-loft. Out there in the yard the noise of the bell was not so bad. In the pigeon-loft, Sappho could have had no idea of the dreadful din she had started in the house. She was talking quietly to Homer and Sophocles, and sipping a little water. Dick flicked back the contact wire. The ringing came to an end.

He had already seen the tiny roll of paper fastened by the rubber band to Sappho’s leg. He had never had to take a message before. Always Peggy or Titty or Roger or Nancy had been there to handle the pigeon. His job had been with the wires and batteries and electric bells. But there was the message and he had to get it. He cooed and croodled to the pigeon as he had heard the others, and Sappho, after a little hesitation, let herself be caught. What could the message be? Something about the gold. What would they say when he brought the melancholy news that it was not gold at all? He pulled out the paper and unrolled it. Only three words. The first time he read it he hardly realised what it meant. He read it again.

‘FIRE HELP QUICK.’

Joke? It couldn’t be a joke. He was out of the pigeon-loft in a moment, slammed the outer door on the startled pigeons, leapt the last eight steps, all but fell, picked himself up and dashed into the house.

‘I’d like to see that bell contrivance of yours,’ Captain Flint was saying as they met in the passage.

Dick held out the scrap of paper with Titty’s desperate message.

‘We’ve been afraid of it all the time,’ he said.

‘Where are they?’ said Captain Flint shortly.

‘At the corner of High Topps, above Mrs Tyson’s farm. At least that’s where the camp is. …’

Captain Flint ran out into the garden and looked up the valley towards Kanchenjunga and that long spur of Ling Scar that held High Topps on its further side.

Yes. The skyline up there was dim and blurred. Smoke was drifting over the top of the ridge.

Captain Flint was back in the house before Dick had had time to join him in the garden.

‘Molly,’ he called, in a voice that brought Mrs Blackett at once to the top of the stairs.

‘What is it, Jim?’

‘What’s old Jolys’ number? …’

‘Seven something. … You’ll see his fire-card on the telephone. What do you want him for?’

‘Fire on High Topps. You be getting the car out while I telephone.’

Captain Flint ran to the telephone. There, pinned to the wall, was a card neatly type-written by Col. Jolys himself.

Captain Flint took off the receiver and violently joggled the bracket. Mrs Blackett, her face white, was gone. There was no time for Dick to make up his mind what he ought to do. The telephone had answered. Captain Flint was talking.

‘Fellside, seven five. … No. … Not nine. … FIVE. … F for fool. I for idiot. … Yes. … SEVEN FIVE. … Hullo. … Hullo. … That Jolys. … Jim Turner speaking. … Oh yes. Back today. … Listen! Fire on High Topps. … What? … Yes. … Got a good hold by the look of it. … Blowing from Dundale. … Southerly. … Right. …’

There was a sudden roar in the yard, Mrs Blackett racing Rattletrap’s engine.

‘Come on, Dick. Hop in.’

‘What about the dromed … bicycle?’ said Dick.

Captain Flint lifted it up and put it into the back of the car, its handlebars and front wheel sticking up above the back seat. The front wheel was still spinning. Dick scrambled in after it. Mrs Blackett slipped out of the driver’s seat to make room for Captain Flint. ‘Oh dear, oh dear,’ she was saying, ‘I ought never to have let them camp up there in this drought.’

‘It’s all right, Molly,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Don’t you worry.’ He clicked the gears in. Rattletrap, knowing her old master, started off as if she meant it. They swung through the gate and sharp right into the road. The gears changed, second … third. … ‘Hold tight, Dick,’ said Captain Flint. ‘She won’t do forty except downhill, but she’s a bit of a broncho round corners. …’

The narrow road was all corners. Dick and the dromedary were sometimes sharing a seat on one side of the car and sometimes on the other. He held on as tightly as he could. Rattletrap had never moved so fast. Even in the front seats Mrs Blackett and Captain Flint were being tossed about as the old car bounced across pot-holes and over loose stones. They were not talking. Once Dick heard Captain Flint say ‘Go it, old girl,’ but he was speaking to Rattletrap, not to his sister. As they roared and rattled and clattered up the valley road they could see dull, grey smoke drifting along above the woods. What had happened up there? Where had the fire started? Was the camp burnt? And Dick remembered how he had tiptoed across it, leaving Dot and Titty and Roger sleeping in their tents. … And the gold wasn’t gold. Every single thing had gone wrong. And now this, worst of all. … What if they were too late?

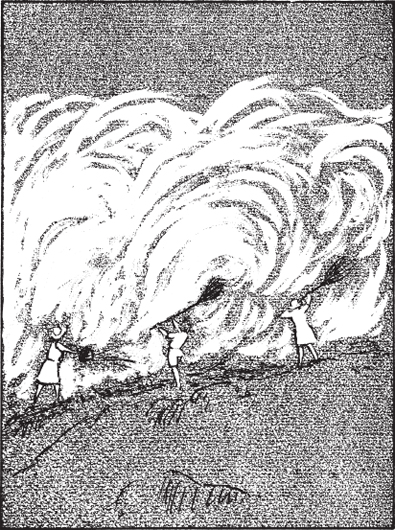

ABLE-SEAMEN FIGHTING THE FIRE

And then, on two wheels, the car shot round, over the narrow bridge, scraping one mudguard, and into the Tysons’ farmyard. It was deserted. Mrs Blackett jumped out of the car as it stopped, and ran across the yard to the path up into the wood.

‘All up at the fire,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Hullo. Good. You’d better take one, too.’

The neat stack of fire-brooms was gone. But three or four of the fire-brooms were lying on the ground where the stack had been. Captain Flint took one and raced up the wood after his sister. Dick took another. He ran after Captain Flint, up and up the winding path. It had been bad enough riding down it on a dromedary. But now, with the fire-broom. … His heart thumped. His breath caught the back of his throat. On. On. His legs ached above the knees. He slipped and hurt his ankle, but in his hurry hardly felt the pain. There was Mrs Blackett. … He caught her up. … He passed her. … He caught just a glimpse of her face as he passed, climbing, climbing. … And now he could hear crackling. The acrid smell of burnt bracken filled his nose and throat at every gasping breath. He shifted the fire-broom to his shoulder. He let it drag behind him on the ground. He lifted it again. Nearly at the top. Gold dissolves in aqua regia. What a donkey he had been. Was Dot all right? Smoke drifted thickly through the trees. Somebody was shouting. …