A voter watches Hillary Clinton’s April 2015 announcement on YouTube that she was running for president. Source: Richard B. Levine/Newscom

6

Social Media

★ ★ ★

A voter watches Hillary Clinton’s April 2015 announcement on YouTube that she was running for president. Source: Richard B. Levine/Newscom

Learning Objectives

Contrast campaigns’ use of social media with their use of other media outlets.

Comprehend the relevant differences between Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms.

149Assess the possible effects of social media campaigning.

Develop a critical grasp of “fake news” and its possible consequences.

Because he won, we sometimes forget that Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign operation was a chaotic mess. As the fall general election campaign began, the Trump team was “woefully behind its . . . opponent in every conceivable metric that scholars study” (Kreiss and McGregor 2018: 173). Trump was skeptical about what he perceived as wasteful spending on ineffective measures, so his campaign spent little on television advertising until the final six weeks of the campaign (Pearce 2016). His campaign farmed out much of its field operations to the Republican party (Confessore and Shorey 2016). Trump attracted far more media coverage than his Republican rivals during the primaries—much of it favorable in tone—but during the general election the amount of news coverage evened out and its tone turned decidedly negative (Patterson 2016), thanks in part to Trump’s countless gaffes and what at the time appeared to be strategic errors.

The haphazard state of Trump’s campaign gave him at least one advantage: he was forced to rely more on social media than conventional modes of communication. Whereas buying spots on television requires at least some advance planning, posting digital spots on social media is conducive to last-minute decision-making and flexibility. The campaign ended up spending half of its media budget on digital advertising, primarily on social media platforms (Persily 2017). Short on time, it leaned heavily on Facebook staffers for input on how to use the platform to reach voters (Baldwin-Philippi 2017). That led to such decisions as using Facebook’s Lookalike Audience feature, which allowed the campaign to target people similar to known supporters and undecided voters (Baldwin-Philippi 2017). An internal Facebook report concluded that “Trump’s FB campaigns were more complex than Clinton’s and better leveraged Facebook’s ability to optimize for outcomes” (Frier 2018).

To make news, there was little need for Trump to employ conventional earned media tactics (although he did grant more interviews than Clinton). He could just hold a rally and make outrageous statements. Hours of “free media” coverage would follow. Or he could just tweet whatever was on his mind. Not only did his tweets reach his thirteen million Twitter followers directly, but they also received secondary exposure as media coverage when the press deemed them 150newsworthy, as they often did. Followers helped spread the word. Trump’s tweets were retweeted six thousand times on average compared with fifteen hundred retweets for Clinton. Trump’s Facebook page had double the number of “likes” as Clinton’s Facebook page, which is partly why his Facebook posts were five times more likely to be shared than Clinton’s (Pew Research Center 2016).

Fake news and other disinformation efforts on social media also favored Trump. The 2016 election triggered alarm about the spread of false or misleading stories on social media—stories that mimic factual news stories produced by mainstream media outlets. Although questions remain about the extent of fake news proliferation and its impact in 2016 (Guess, Nagler, and Tucker 2019), researchers have established that false stories on social media heavily tilted in favor of Trump over Clinton (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017). Trump also was the intended beneficiary of Russia-sponsored digital ads aired on Facebook and other social media outlets aimed at depressing turnout among likely Clinton supporters, particularly African American voters (DiRiesta et al. 2018). For example, Russia’s Internet News Agency created a fake Facebook account called Blacktivist, whose posts included a plea for African Americans to vote for Green Party candidate Jill Stein. Another Blacktivist post declared that “NO LIVES MATTER TO HILLARY CLINTON. ONLY VOTES MATTER TO HILLARY CLINTON.” A third declared that “NOT VOTING is a way to exercise our rights” (Hohmann 2018).

According to conventional wisdom, social media helped Trump win the election despite being pummeled by the press, outspent on television, and outorganized in the field. We will never know if that was true. It may be that Trump’s overall social media operation was no more innovative than Clinton’s (Baldwin-Philippi 2017). As we will see in this chapter, recent research casts doubt on the reach and impact of fake news (Grinberg et al. 2019; Guess, Nagler, and Tucker 2019). In any case, Clinton actually won more votes than Trump nationwide; his victory through the Electoral College could have been explained by any combination of factors. While it is true that Clinton ran far more ads on television, their relentless focus on attacking Trump’s character rather than providing policy-related contrasts may have spurred backlash among some voters (Fowler, Ridout, and Franz 2016). Finally, the “Comey letter” may have been more consequential than any other factor: just a week and a half before the election, FBI director Jim Comey sent a letter to Congress announcing an expansion of the agency’s investigation of Clinton’s use of a private email 151server, which may have shifted the electorate by three or four points—enough to help Trump win Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin and therefore the Electoral College (Silver 2017).

All of this said, even if social media’s importance was overstated, a Twitter-less and Facebook-free Trump campaign is difficult to imagine. Trump’s embrace of social media platforms embodies their promise as outlets for reaching voters. As with earned media, campaigns can use social media to communicate with voters at little or no cost. As with paid media, the campaign has almost complete control over the content and production of the message. But as we will see in this chapter, social media is more promising than either earned media or media as a mechanism for controlling the chaos that characterizes election campaigning. That is because of three distinguishing characteristics that set social media apart from both:

Direct voter contact. Donald Trump’s Twitter feed is a reminder that candidates can use social media to reach voters directly with their own content at a time of their choosing. No need to pay thousands of dollars to run an ad on television that reaches the wrong voters. No need to hold a press conference or grant an interview that will be covered ways that reflect the media outlet’s priorities, not the candidate’s. Instead, the campaign can post its own content—text, video, imagery, or all of the above—onto any or all social media platforms. A video’s duration can be thirty seconds or thirty minutes. The candidate can post multiple times a day at no additional cost. Each post can be seen by anyone with a social media account. At minimum, it will be viewed by people who “like” or follow the candidate on social media.

Supporter sharing. A campaign’s social media posts can be amplified if followers share them with people in their social media network. Social media’s sharing capacity is an example of how campaigns can use these platforms to empower supporters to engage in “digital circulation” of campaign content on behalf of their preferred candidate (Baldwin-Philippi 2015). Supporters can also create their own posts—a tweet, for example, that ridicules a gaffe committed by the opposing candidate. But “social sharing” is easier than creating original content: all a supporter needs to do is use the appropriate function (“share” on Facebook; “retweet” on Twitter) to spread the candidate’s post or other content that helps the candidate’s cause. Even clicking on the “like” button or heart icon can expose the post to people in the user’s network. A particularly compelling post can go viral.

Supporters share campaign-generated content on social media “because they find it compelling, want to help a candidate or cause, 152or want to signal their identity” (Kreiss 2016: 220). “Opinion leaders”—influential people within a network—are seen by campaigns as particularly important sharers (Baldwin-Philippi 2015). Their efforts may bear fruit: social media users are more likely to read political content if it is shared by actual friends and family. That applies even among recipients who are “entertainment seekers,” and even when the shared content comes from a partisan source they disagree with (Anspach 2017).

Microtargeting. As we saw in the previous chapter, social media outlets provide effective platforms for online advertising that is microtargeted to individual voters based on their estimated predispositions. People reveal a large amount of politically relevant information about themselves on their social media profiles. An individual’s gender, age, geographic location, profession, and interests are easy to discern; all serve as predictors of a person’s political orientation and voting behavior. Likes and follows are particularly revealing, especially when a person likes or follows individual candidates or political causes. Liking a particular celebrity also might reveal something useful about a person’s politics. Digital ads are not limited to social media; Google rivals Facebook as a top site for online campaign advertising. But social media platforms are appealing to campaigns because users share so much that is politically relevant about themselves.

These three qualities do not assume the campaign has complete control over what happens on social media. Each platform’s proprietary algorithms shape what people see on their feeds, which means a user might not see a candidate’s post if the formula predicts a lack of interest. In addition, a clumsy social media post can become an unflattering news story. That happened to Republican presidential candidate Rand Paul when he misspelled the word “friendship” in a tweet mocking two of his potential GOP 2016 rivals for their shared support for unpopular “common core” education. A post can be humiliating when it goes viral as a target of ridicule. Critics can use the comment function to respond to the post in ways that undermine the post’s intent. Users can ignore the comments, but sometimes they take on a life of their own. On Twitter, for example, a tweet can be “ratioed” when the number of replies exceeds the amount of retweets—an embarrassing indicator of a mostly negative reaction to the post.

An individual’s social media behavior can also be misleading. Just because someone likes a candidate on Facebook does not mean she can be counted on as a supporter. Donald Trump has plenty of Twitter followers who have no intention of voting for him.

153The campaign’s digital team, usually led by the digital director, is typically responsible for social media outreach along with online advertising, email, and the web site (see box 6.1, “The Online Communication Hub.”) Social media is a useful broad category for the sake of organizing campaign communication efforts, but each platform is quite different. What they have in common is a capacity to enable users to create and share content with each other through online social networks. They differ significantly in terms of their audiences and functionality. These differences are constantly changing as each platform adjusts to shifting preferences, technological advances, and policy constraints. Whereas the basic format of the traditional thirty-second television spot has remained the same for more than forty years, social media platforms make frequent adjustments—often without warning—every election cycle (Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018), and sometimes in the middle of an election cycle (Kriess 2016). Understanding the differences between each platform is a must, with the caveat that the distinctions described below are highly subject to change.

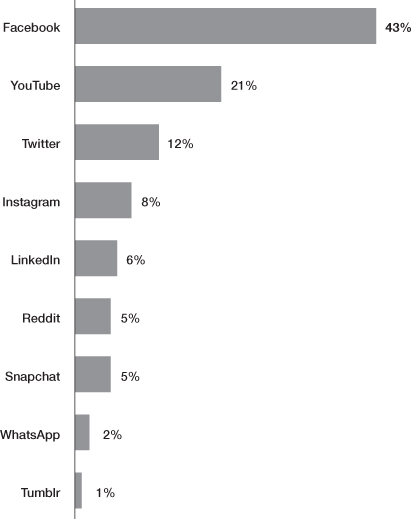

154Facebook remains the dominant social media outlet. Sixty-eight percent of U.S. adults reported using Facebook in 2018. Facebook may have a reputation for appealing to older audiences, but 80 percent of 155 adults aged eighteen to twenty-four reported using it—pretty close to the number associated with this age group’s Snapchat use in 2018 (Smith and Anderson 2018). As figure 6.1 shows, it was a much more important source for news than the other social media outlets: 43 percent of U.S. adults reported getting news from Facebook compared 156with only 12 percent for Twitter, 8 percent for Instagram, and 5 percent for Snapchat (Shearer and Matsa 2018).

Figure 6.1 Social Media Sites as Pathways to News. Percentage of U.S. Adults Who Get News on Each Social Media Site

Source: Survey conducted July 30–August 12, 2018. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2018.” Pew Research Center N = 4,581. Margin of error: ±2.5%.

Facebook’s massive reach across demographics makes it irresistible to campaigns. Social media strategists for 2016 presidential candidates, interviewed by a group of scholars, had this to say about the platform’s audience (Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018: 16):

The majority of Americans are on Facebook so it was our biggest platform, our most diverse one. We could really try to get young Latinos, to older African-Americans of the South, to blue-collar workers in the Midwest. Really, the audience was everyone.

Facebook is obviously the 800-pound gorilla of social platforms. . . . Facebook is going to provide you probably the broadest range of age groups that you can find.

Facebook was our biggest source of traffic. It was our biggest source of engagement and so if we ever had something, Facebook always came first in my mind in terms of where to go with something. It was our most diverse audience.

Campaigns strategists also appreciate Facebook’s capacity to collect and exploit highly specific data about individual users—not only their likes and dislikes but also their apparent political orientations and behavior. These data can be used to microtarget customized campaign ads. Leading up to the 2016 election, Facebook’s sales pitch to political campaigns touted its ability to connect voter files with individual data collected through users’ online activity—not only their social media behavior but also their online purchases (Bump 2014). That capacity came under scrutiny when Cambridge Analytica, a strategic communications firm hired by the Trump campaign in 2016, collected more data than people were comfortable with, forcing Facebook to adjust its data-sharing policies. But campaigns will take whatever individualized data they can get. A user’s decision to like a dozen or so Democratic candidates—and no Republican candidates—tells a campaign where that person leans politically. A person who shares stories posted by a right-wing media outlet is a safe bet for Republican messaging. Consider Facebook’s “I Voted” button. For years, Facebook has hosted programs aimed at boosting voter turnout, including the Election Day display of either an “I Voted” or “I’m a Voter” button that allowed users to boast to their friends about performing their civic duty. Users who clicked on that button are revealing useful data about themselves: not only did they vote, but they were also willing to encourage their friends to do the same.

Facebook’s versatility is another plus (Kreiss, Lawrence, and MacGregor 2018). It hosts a dizzying array of features, many of them 157borrowed or influenced by other social media outlets. The Facebook “stories” feature resembles the Snapchat function of the same name. Like Twitter’s Periscope and Instagram Live, Facebook Live allows users to stream live video. In 2016, the Trump campaign streamed its own Facebook Live broadcast of the third presidential debate for which Trump surrogates replaced journalists as pre- and postdebate analysts. Nine million people watched Trump’s Facebook broadcast, and the campaign raised $9 million in contributions during and immediately after the event (Persily 2017).

As with most social media platforms, Facebook users see content through their newsfeeds. Facebook newsfeeds display a constantly updated series of posts by friends in users’ networks and pages they like. On Facebook, friends can range from a lifelong pal to someone the user met in class yesterday. Users can “friend” a parent, professor, or coworker. Facebook friendship networks can include distant relatives and childhood classmates. As a result, Facebook networks can be more politically diverse than friendships based on interpersonal contact (Thorson, Vrega, and Kriger-Vilenchik 2015). People are more likely to encounter a wider range of political viewpoints on Facebook than they do elsewhere. For campaigns, that means users see posts about candidates and causes they both support and oppose. Uncommitted users can see posts not only by candidates vying for their vote but also by friends attempting to change their minds.

The most straightforward way for candidates to establish a Facebook presence is to launch a page. Ideally, a candidate’s Facebook page is “liked” by existing and potential supporters (although opponents may also like the page for the sake of monitoring or merely curiosity). To build followers, a campaign can start by emailing the Facebook page link to existing supporters and uploading its email list to the “Suggest Page” function. Theoretically, users who like a candidate’s page will see all of the candidate’s posts as they go live. In reality, the Facebook algorithm prioritizes posts that it projects will lead to active engagement such as commenting and sharing. There is a good chance a post will get buried except for those users who have actively responded to the candidate’s past posts.

What do candidates post? They can share their reactions to current events. They can post videos of rallies and speeches. They can share different versions of their television spots—longer versions, perhaps those with edgier content. Candidates can link to news articles and commentary they like. In practice, posts tend to “facilitate interpersonal connections rather than provide policy information” 158(Baldwin-Philippi 2015: 9). Strategists for several of the 2016 presidential candidates said they used social media “in a way that fit with and conveyed the ‘authentic’ voice of their candidates” (Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018: 13). For Jeb Bush, “that was everything from showing that he was a policy nerd and an introvert.” Bernie Sanders also wanted to focus on issues, not photos of his meals or a cat (Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018: 14). Younger, more tech-savvy candidates are more comfortable with posts that show their human side—if not photos of the candidate’s cat or food, then perhaps a live video of the candidate interacting with neighbors or hanging out with the family.

Twitter’s audience is much smaller than Facebook’s; about one in four U.S. adults reported using Twitter in 2018 (Smith and Anderson 2018). But for campaigns, what is notable about Twitter is its importance as a news platform and the high level of political engagement of its audience. Three in four Twitter users rely on Twitter for news (Shearer and Matsa 2018). Twitter users tend to be more interested in politics and more likely to vote than the average person, and “wealthy enough to contribute to campaigns” (Bode and Dalrymple 2016: 326). Politically speaking, the audience is small but mighty. That makes Twitter a promising setting for two-step flow communication whereby candidates first influence highly engaged opinion leaders who are active on Twitter. These “influencers” then share what they know and think to their less engaged friends and family members (Kreiss 2016; Bode and Dalrymple 2016; Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955).

Originally a simple text-based platform, Twitter has gained features over time. A user’s newsfeed displays a stream of text-based “tweets,” which, until recently, appeared in chronological order as they were posted. Tweets are brief, capped at 280 characters (double the original 140-character limit). Originally text-only, users have been able to tweet images and video clips since 2010. Many users rarely post their own tweets—only half of users actually tweet—but they do actively engage with tweets posted by others: tweets can be liked, retweeted, and commented on.

For many users, Twitter serves as more of a new aggregator than a platform for interacting with friends and family. Users “follow” other Twitter accounts to see their tweets. People can follow their friends on Twitter, but they are more likely to follow celebrities and 159public figures—candidates, for example. The Twitter feed of a politically engaged individual will display a stream of tweets by politicians, media outlets, individual journalists, pundits, activists, and commentators (along with tweets related to their other interests).

A candidate can create a Twitter account in minutes. Another few minutes and the candidate is reaching potential voters directly through tweets of 240 characters or less. But a strong Twitter presence depends on followers. Attracting followers is easy if the candidate is a celebrity like Donald J. Trump, who already had more than four million followers when he declared his presidential candidacy in 2015. Lesser known first-time candidates face a significant challenge. A candidate can start by following other prominent people on Twitter: other public figures, journalists covering the race, as well as activists and other political “influencers.” These tweeters will be notified that the candidate is following them and may return the favor (a journalist covering the race will be compelled to do so). They also will be notified if the candidates likes, retweets, or comments on their tweets, which also may attract additional followers.

Another challenge is getting followers to see a candidate’s tweets. As with Facebook, a user’s default time line is “curated” by an algorithm that shows top-ranked tweets first, above more recent tweets displayed in chronological order. Predictable tweets are likely to get buried. They also are less likely to result in active engagement by opinion leaders in the form of likes or retweets. Tweeting good news about polls and fundraising is a safe bet, but Twitter is conducive to spontaneity and unscripted commentary. Clever reactions to headlines are more likely to yield active engagement and news coverage, but controversial tweets can backfire. In 2016, the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) posted a tweet accusing Senate candidate Tammy Duckworth of having a “sad record of not standing up for our veterans.” This was a gaffe: a veteran herself, Duckworth had lost both legs in combat during the Iraq War. The NRSC deleted the tweet (Kreig 2016).

For better or worse, candidates can make news on Twitter partly because the platform is so popular among journalists. That makes it a versatile earned media tool—the topic of chapter 4. In that chapter, we examined the strategies campaigns use to “manage the news” through their interactions with media outlets. For journalists covering campaigns, Twitter is an essential tool because they can follow their sources—candidates and pundits—as well as fellow journalists and competing news outlets. Election news breaks on Twitter. Candidates 160can tweet their reactions to events before they issue a statement. When news breaks, communication operatives can tweet their “spin” because they know journalists are constantly scanning their Twitter feeds for leads. Reporters are also monitoring each other’s tweets, following their competition for scoops, sensitive to the possibility of missing something important. A New York Times reporter described Twitter’s importance to journalists covering the 2012 election:

It’s the gathering spot, it’s the filing center, it’s the hotel bar, it’s the press conference itself all in one. . . . It’s the central gathering place now for the political class during campaigns but even after campaigns. It’s even more than that. It’s become the real-time political wire. That’s where you see a lot of breaking news. That’s where a lot of judgments are made about political events, good, bad or otherwise. (Hamby 2013: 24)

For many users, Twitter serves as a “second screen” during live events such as debates and conventions (Gil de Zúñiga, Garcia-Perdomo, and McGregor 2015; Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018). Like many people, journalists watch live campaign events with one eye on the TV or computer screen and the other on their Twitter feed. That is because both their sources and fellow journalists “live-tweet” the event as it occurs. During a debate, for example, a journalist’s Twitter feed acts as live focus group providing continuously streaming assessments of how the candidates are doing and which moments stand out as newsworthy (Schill and Kirk 2015). Twitter blows up when a candidate commits a gaffe or goes on the attack. Knowing that journalists are monitoring Twitter, members of the campaigns’ communication teams and their surrogates post their own live tweets and encourage supporters to do the same (especially those with a large number of followers). Campaigns know the debate’s media coverage will center on the horse race—who won and who lost (see chapter 4). They use Twitter to attempt to “spin” those assessments by providing live commentary as it happens and immediately after it occurs.

Instagram and Snapchat

Facebook and Twitter may grab headlines, but audiences are flat for both. Instagram, Snapchat, and other platforms have seen rapid growth in recent years, especially among younger audiences. Snapchat attracted 78 percent of U.S. adults aged eighteen to twenty-four in 2018; Instagram drew 71 percent of people in this age group (Smith and Anderson 2018). Neither were used much for news (Shearer and Matsa 2018). Even so, social media operatives for the 2016 presiden161tial candidates viewed Instagram and Snapchat as “a way to reach younger audiences seeking backstage and behind-the-scenes looks at candidates and life on the campaign trail” (Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor 2018: 18).

Instagram shares key features with both Facebook and Twitter. As with both, it costs nothing for a candidate to create an Instagram account. Users follow other Instagram accounts to see their posts. Posts can be liked, commented on, and shared. But Instagram posts are limited to images and video. They can include text, but only if the text is embedded in an image or typed into the comments. It is common for campaigns to use Instagram to share photos and videos of the candidate interacting with voters on the campaign trail. Posts tend to be informal, intended to portray the candidate’s human “nonpolitician” side. The live-video function allows candidates to interact with voters in real time. Sometimes these efforts fall flat. For example, Elizabeth Warren was ridiculed for awkwardly drinking a beer during a live video chat launching her 2020 presidential campaign.

Snapchat was once less useful to campaigns because of its original focus on person-to-person sharing of photos (“snaps”) and brief videos that disappeared after ten seconds. But its “stories” function allows users to share content for up to twenty-four hours. And its “Discover” function hosts targeted advertising. In 2016, the platform launched programs aimed at reminding people to vote, streamed election results on Election Day, and shared election-related “geofilters.” As with Instagram, Snapchat is used by campaigns as a platform for digital messages targeted at young voters. Bernie Sanders used Snapchat to reach the youth vote during his Democratic nomination race in 2016. Doug Jones used it to target young African American voters when he ran for U.S. Senate in Alabama in a special election in 2017. “The Snapchat geofilter option was a great solution for homing in on the younger African-American demographic, without advertising to the more conservative voters that surrounded them,” said Andy Amsler, who helped lead Jones’s digital strategy. “They took our message, personalized it, and then broadcasted it out to their friends and their networks” (Barrett 2018).

YouTube

YouTube stretches the definition of social media. Users rarely build online YouTube identities in the way they do on other platforms. Most users treat it as a medium for watching videos on demand. But like the 162other social media platforms, users can create and post their own content. YouTube’s original motto was “Broadcast yourself,” an indicator of its early emphasis on original videos produced by amateur users. And YouTube makes it easy for users to share videos not only by email but also through their social media accounts. Videos “go viral” when they are shared by thousands if not millions of users on a social media platform like Facebook. Videos can be liked and commented on. Clearly there are social, user-centered aspects to YouTube.

YouTube’s reach makes it irresistible to campaigns. According to Alexa’s “Top Sites” service (https://www.alexa.com/topsites), YouTube was the second most popular website in the U.S. in 2018 behind Google, its parent company (Facebook was third). Three-quarters of U.S. adults said they used the site in 2018 (Smith and Anderson 2018). Thirty-eight percent of them used it for news (Shearer and Matsa 2018).

YouTube is owned by Google, which means users’ search histories can be tapped for microtargeted video spots and display ads. Campaigns can pay to run particular ads for individuals who visit the site or watch a video. But it is the ability to post and share unlimited video content at no cost that makes YouTube essential even to campaigns with limited resources. Campaigns can post—and encourage their supporters to share—their standard thirty- and sixty-second spots produced for television on their YouTube account for free. They can also post longer spots that bend the creative norms of political advertising. For example, a 2016 Ted Cruz video depicted three kids playing with a Trump action figure and mocking it for being “too big to fail” and pretending to be a Republican. A satirical Cruz video depicted well-heeled lawyers, bankers, and journalists splashing through the Rio Grande River, which defines the U.S.–Mexico border, to dramatize the economic costs of illegal border crossings. When Carly Fiorina ran for the Senate in California in 2010, her campaign produced a lengthy video that came to be known as the “demon sheep” ad. The objective was to warn voters about the conservative bona fides of Fiorina’s Republican primary opponent. The “demon sheep” appeared near the end of the spot: a man in a sheep’s costume with glowing red eyes, hiding among innocent sheep grazing in a meadow—“a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” the narrator says, “Has He Fooled You?” the on-screen text asks. The ad was too long and too bizarre for television, but tens of thousands of people viewed it online.

YouTube also serves as a home for documentary-style videos that run minutes long. One example is the two-minute Ocasio-Cortez 163video analyzed as a case study in chapter 4. Another example was a three-and-a-half minute video introducing voters to M. J. Hegar, an Air Force helicopter pilot who challenged Rep. Joe Carter for Texas’s Thirty-First Congressional District in 2018. Called “Doors,” the cinematic video referenced a variety of momentous doors in Hegar’s life: a door from her helicopter that crashed after being shot in Afghanistan; the glass door through which her abusive father pushed her mom; the Capitol Hill office doors slammed in her face when she lobbied Congress on women serving in combat; and her promise to “show the door” to her opponent. Hegar lost the deep-red district by only three points, but not before her video went viral, having been shared by the likes of Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda and actress Kristen Bell. Paying to air a video like this on television would be prohibitively expensive, but it streamed on YouTube for free. And because it was widely shared on social media, thousands of voters saw the ad (as did thousands of people outside of the district). So did donors and media outlets.

A campaign’s YouTube page can host all of the campaign’s videos: not only ads and minidocumentaries but also full candidate speeches, debate performances, rally footage, and testimonials. The site can also host campaign-approved amateur videos produced by supporters. When Bernie Sanders ran for president in 2016, his campaign posted a three-minute “Guide for Canvassing” video aimed at easing volunteers’ concerns about knocking on doors. Similarly, Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign shared a video on “How to Canvass in Nevada,” which offered advice on attire, demeanor, safety, how to use the script and walk list, what to say to voters, and—for out-of-state volunteers—how to pronounce the state’s name correctly (“I hAd a blast in NevAda”). Sharing the video with volunteer canvassers was just a matter of providing the link to volunteers.

Email is old technology, and not widely seen as a form of social media. But like social media, email is often the responsibility of a campaign’s digital team. And in some ways, it is a more important platform for campaigns than either Facebook or Twitter. Nearly all U.S. adults use email at least occasionally, and about 60 percent send and receive emails every day (Heimlich 2010). As with other forms of social media, users can create and share content with people in their networks. And 164email is a proven platform for fundraising (Green 2012). Most of the money raised online by the 2012 Obama campaign came in response to email messages. “People talk about Instagram and Snapchat and all these different digital platforms, but good ol’ email remains the most crucial,” said political scientist Ken Goldstein in an interview with National Public Radio (Anderson 2016). According to a digital staffer from the 2012 Obama campaign, “Social is good, social matters, but email is what rationalizes the existence of the [digital] program” due to its fundraising capacity (Kreiss 2016: 198).

As with other social media platforms, emails can be microtargeted. If a person is willing to share their email address with a campaign or any sort of political cause, that is enough for a campaign to make assumptions about that person’s political leanings. It helps when the person also shares their zip code and answers a battery of political questions. The email address can be linked with that person’s online identity, about which there will be data on various likely political orientations and behavior. That explains why one’s email inbox can be filled with pleas for help, especially in the form of campaign contributions—even from candidates they did not sign up for. Campaigns also use their email lists to circulate online videos, information on volunteer recruitment efforts, and get-out-the-vote messaging. One objective is to encourage recipients to share the email with others in their network. That can happen organically, but campaigns can facilitate sharing by including a button or link labeled with something along the lines of “forward to a friend.”

The subject lines of those emails are designed to be attention-grabbing so that people open them. “Hey” and “Are You Awake?” were subject lines for the Obama campaign in 2012. Sometimes the subject line is personalized to include the recipient’s name. In 2016, the Clinton campaign sent a series of emails with subject lines like “I’m not kidding, David.” The body of the email continued, “I’m not kidding, David. I’m asking you to donate $1 right this second.” The subject line for an email sent on the evening of one of the Democratic primaries read, “We may not win tonight, David.” That alarmist language is typical. During the general election, the Trump campaign sent an email with the subject line, “Breaking: Hillary to Be Indicted in November” (Anderson 2016).

Campaigns can assess the effectiveness of the wording of the subject line as well as other element of an email. They can collect data on whether an email was opened, what links were clicked, and whether the links were shared on other social media platforms (Baldwin-Philippi 1652017). That makes email ideal for A/B testing—the practice of systematically comparing responses to one message (A) versus another (B). For example, a campaign can send the same email to two groups of people but vary the wording of the subject line. If subject line “A” has a higher open rate than subject line “B,” the campaign can adapt A’s subject line for future email messaging. The results of these tests inform not only future email efforts but also wording decisions for other aspects of the campaign.

Impact

Does it work? Does campaigning on social media influence voters as intended? The answer is complicated. Campaigns use social media in a variety of ways. Much of their social media activity falls under the category of paid media. When campaigns pay to run digital ads on Facebook and other social media platforms, assessing effectiveness is similar to measuring the impact of TV spots but with more metrics about engagement. chapter 4 reviewed this rich literature and reported mixed results. Under some circumstances, campaign advertising can influence enough voters to decide a tight race. But sometimes the impact of campaign advertising is minimal, especially when the airwaves are saturated with political spots from both sides. In addition, the effects of advertising fade pretty quickly.

Why would effects be different when ads are streamed on social media rather aired than television? Perhaps the ability to microtarget customized ads to individual voters based on their likes and dislikes promises more opinion change. That is what Donald Trump’s digital operation assumed. Half of the campaign’s budget went to digital advertising in 2016 (Persily 2017), mostly on Facebook (Baldwin-Philippi 2017). It spent half a million dollars to buy YouTube’s banner ad on Election Day. To gauge the effectiveness of its digital spots, the Republican National Committee claims it ran forty thousand to fifty thousand variants of its ads, making minor tweaks to format and content to see what worked best (Lapowsky 2016). Unfortunately, there is little academic research measuring the impact of digital advertising aired on social media. What little research exists casts doubt on the assumptions made by digital media strategists. One study suggests that Americans saw very little political advertising on Facebook during the 2018 midterms. Exposure was limited to regular Facebook users and those were very conservative or very liberal (Guess, Nagler, and Tucker 2019). A pair of studies assessed the effects of a high 166volume of targeted Facebook ads supporting candidates for legislative seats—one at the state level, the other for the U.S. Congress. In both cases, ad exposure was associated with a higher likelihood of recalling the candidate’s name, but no apparent impact on how favorably the candidate was evaluated (Broockman and Green 2014). In other words, persuasion effects were minimal.

But campaigning on social media involves more than paying for online advertising. Social media allow candidates to use their own free posts to reach voters directly, sometimes avoiding the scrutiny of news media and minimizing the high costs associated with paid advertising. For all the money the Trump campaign spent on Facebook advertising, his unfiltered tweets reached millions of followers at no cost (albeit with plenty of media scrutiny). In addition, much of social media’s promise as a campaign tool lies in its capacity for supporter engagement. Social media empower supporters to do their own campaigning on behalf of—and in opposition to—particular candidates and causes. What is the impact of the social media campaigning that does not entail paying for advertising?

Theoretically, social media messaging could be unusually effective. People may be more likely to let their guard down on social media than they do when consuming election news or encountering a campaign spot. Except for Twitter, social media are primarily used for maintaining social ties, not gathering political information. Rather than seek out political content, users encounter election-related posts incidentally as a byproduct of a nonpolitical social networking and entertainment. Users who are otherwise disengaged probably have social media friends who actively post about politics. These are people they know and trust. That matters because people are more likely to view information they receive from a trusted source as credible (Bode 2016a).

Research assessing social media’s electoral impact suggests mixed results. Much of the research centers on how much people learn and whether social media boost voter turnout and other forms of participation. The results are mixed enough to raise doubts about whether social media deliver on their early promise to foster healthy democratic behavior. Although some studies report positive influences (Bode 2012, 2016a; Bond et al. 2012; Dimitrova et al. 2014; Skoric et al. 2016; Valenzuela, Park, and Kee 2009; Vitak et al. 2011), others call into question whether social media encourages either political learning (Baumgartner and Morris 2010; Conroy, Feezell, and Guerero 2012; Dimitrova et al. 2014; Towner and Dulio 2015) or 167political participation (Baumgartner and Morris 2010; Dimitrova and Bystrom 2017). The absence of consistent effects can be partly explained by users’ contradictory preferences about politics on social media. According to one study, Facebook users dislike highly opinioned political posts (Thorson, Vrega, and Kliger-Vilenchik 2015). It is no secret that social media users can block, unfriend, or hide someone for political reasons, although such behavior is less common than people think (Bode 2016b). People seem to prefer neutral political content. But balanced posts are less likely to be read (Thorson, Vrega, and Kliger-Vilenchik 2015). Although people are exposed to a wide variety of political viewpoints on social media, they are selective about what they pay attention to and take seriously.

Of course, what campaigns want to know is whether their nonadvertising social media activity yields more votes for their candidate. Here, what little research exists is revealing. In one study, actively sharing political content on Facebook or Twitter was associated with participating in the Iowa caucuses whereas passively following a candidate on social media was not (Dimitrova and Bystrom 2017). This finding is consistent with research showing that effects are limited unless the user actively engages with social media content (such as posting comments). Passively following a candidate on Facebook is not enough (Gil di Zúñiga et al. 2013).

“Fake News” on Social Media

Much of the conversation about social media has centered on the effects of the spread of “fake news.” As president, Trump has used this term to discredit responsible media outlets and news stories that are critical of his behavior. But fake news once meant something else. The original conception of fake news refers to “fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent” (Lazer et al. 2018: 1094). Concerns about this form of fake news escalated during the 2016 election, and Trump stood to benefit, not suffer. According to one analysis, the twenty most popular false news stories generated about 8.7 million shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook during the final three months of the election, outperforming the twenty most popular election stories produced by mainstream news outlets. All but three of the twenty false stories were overtly pro-Trump or anti-Clinton. These stories made absurd claims. One of the most popular stories claimed that Clinton sold weapons to ISIS when she served as secretary of state (Silverman 2016).

168Some of the fake news was organically produced and shared by individual partisans in the U.S., especially those on the right. But much of it was traced to Russian efforts to disrupt the U.S. election (Lazer et al. 2018). A slew of false pro-Trump and anti-Clinton stories were posted on about 140 websites maintained by teenagers in the small Balkan town of Veldes, Macedonia. Locals there reportedly made as much as $3,000 per day from millions of page views of articles they copied and pasted from right-wing media in the U.S., then shared on Facebook. One of their most successful posts falsely claimed that the pope had endorsed Trump. Another reported that Clinton had once said, “I would like to see people like Donald Trump run for office; they’re honest and can’t be bought.” During the primaries, the group experimented with posts promoting Bernie Sanders, but discovered that pro-Trump falsehoods performed far better (Silverman and Alexander 2016). The operation was reportedly launched by a Macedonian media attorney working with two American partners (Silverman et al. 2018), who themselves made so much money with their own fake news websites that they felt “uncomfortable talking about it because they don’t want people to start asking for loans.” Their website featured headlines like “BREAKING: Top Official Set to Testify Against Hillary Clinton Found DEAD” and “BREAKING: Michelle Obama Holds Feminist Rally at HER SLAVE HOUSE” (McCoy 2016).

Academic research confirmed the pro-Trump tilt of fake news during the 2016 election (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017). At least one study suggested that exposure to fake news had an impact on some voters’ decisions in 2016. Specifically, voters who supported Obama in 2012 but defected to Trump in 2016 were unusually likely to believe three of the most popular false rumors circulating on social media: that the pope had endorsed Trump; that Clinton had sold weapons to ISIS; and that Clinton was in poor health due to serious illness (Gunther, Beck, and Nisbet n.d.).

How does fake news spread? Social bots play a role. Social bots are artificial intelligence systems that “are set to automatically produce content following a specific political agenda determined by their controllers, who are nearly impossible to identify” (Ferrara 2016). Bots not only generate their own posts but they can also be programmed to share, like, retweet, and even comment on other posts. According to one study of Twitter behavior, bots were responsible for about 3.8 million tweets during five weeks in September and October 2016, which amounted to about one-fifth of the conversation about 169the presidential election (Bessi and Ferrara 2016). That mattered because tweets posted by bots were retweeted at the same rate as tweets posted by humans. And they produced content automatically at breathtaking speed (Ferrara 2016).

Yet robots alone should not be blamed for spreading fake news. One groundbreaking study of Twitter activity from 2016 to 2017 found that humans spread false news at the same rate as bots. A false story is much more likely to go viral on Twitter than a true story, the authors concluded. Compared with stories based on accurate reporting, false stories reached more people, penetrated social networks more deeply, and spread much faster. False news about elections and other political topics was particularly susceptible to viral distribution compared with news about such topics as terrorism, science, and entertainment (Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral 2018).

In wake of the 2016 election, lawmakers intensified their scrutiny of social media’s role in spreading misinformation. Facebook and Twitter responded to the pressure by undertaking a variety of measures to stem the flow: hiring more human monitors, upgrading machine-based monitoring, and detecting and closing down fake accounts (Harvey and Roth 2018; Mosseri 2017). One study indicated that Facebook’s efforts had been successful as of summer 2018 (Allcott, Gentzkow, and Yu 2018). Yet reports of orchestrated efforts to spread fake news persist. A full year before the 2020 presidential primaries, several of the 2020 Democratic hopefuls were targeted on social media with misleading memes and hashtags aimed at sowing divisions within the party. For example, a widely shared grainy screenshot taken during Elizabeth Warren’s Instagram Live candidacy announcement allegedly showed a blackface doll on top of her kitchen cabinet; a closer look revealed that the object in question was actually a vase. A tweet viewed by millions of people promised (but did not deliver) breaking news about Beto O’Rourke leaving a racist message on an answering machine in 1990s (Korecki 2019).

How widely do these stories circulate? Do they change people’s minds? There are reasons to be skeptical about their reach and influence. Numerous studies have confirmed that conservatives or Trump supporters were more likely to consume and share fake news during the 2016 election than liberals or moderates (Grinberg et al. 2019; Guess, Nagler, and Tucker 2019; Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler 2018). Sharing fake news was far more common among people over the age of sixty-five than people in the youngest age groups (Guess, Nagler, 170and Tucker 2019). Mostly these were people who had already made up their minds about supporting Trump.

Overall, however, very few people engaged in any form of fake news dissemination (Guess, Nagler, and Tucker 2019). According to one study of Twitter use in the 2016 election, only 0.1 percent of individuals accounted for 80 percent of shares from fake new sources. These “supersharers”—probably “cyborgs,” or “partially automated accounts controlled by humans”—tweeted an average of seventy-one times per day whereas a typical person tweeted a few days a week (Grinberg et al. 2019). It is also possible that relatively few people saw or remembered many fake stories in 2016 (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017). One study of web traffic data estimated that only 27 percent of Americans visited fake news websites during the final five weeks of the 2016 campaign. Visits to fake news sites may have actually dropped during the 2018 midterms (Guess et al. 2019). Even in 2016, most of the visits to fake news sites were among the 10 percent of people with the most right-leaning media diets (Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler 2018). These were not persuadable voters. Heavy fake news consumers already had highly skewed information diets. For them, fake news was comfort food that merely reinforced their predisposition to vote for Trump. For most voters in 2016, mainstream news outlets remained the most important sources of information (Grinberg et al. 2019).

CONCLUSION

Perhaps other fears about social media are also overblown. Social media’s growth has intensified long-standing concerns about the enhanced ability of people to isolate themselves into like-minded media “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” (Sunstein 2009; Pariser 2011). If true, that would challenge any campaign’s effort to reach cross-pressured voters from the opposing party. But academic research provides mixed results here. Although people do seem to seek out information that supports their existing opinions—conservatives do gravitate toward Fox News and liberals to MSNBC—they do not necessarily avoid perspectives that challenge their predispositions. Most people who follow politics closely “have largely centrist information diets” despite the availability of partisan media outlets (Guess et al. 2018: 9). Political news websites tend to attract ideologically diverse audiences, calling into question the notion of a red/blue divide in internet use (Nelson and Webster 2017).

171Social media may actually help, not hurt. On Twitter, people tend to follow media accounts on both ends of the political spectrum (Eady et al. 2019). Facebook users disagree with more of their Facebook friends than they think (Goel, Mason, and Watts 2010). People can “unfriend” users they object to, but only one in ten Facebook users does so (Bode 2016b). Their newsfeeds display perspectives they disagree with as well as news and information from sources they would not normally seek out (Messing and Westwood 2014; Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic 2015).

All of this means campaigns can enlist their supporters to use social media to connect with voters who might otherwise be difficult to reach. Political posts carry a lot of weight when they come from a credible opinion leader or friend who is trusted for their political judgment. Even so, campaigns can be remarkably cautious about empowering supporters to go beyond standard sharing and commenting. “In the end, digital and social media might largely constitute another set of channels and platforms for communication rather than a revolution in terms of overall campaign strategies” (Svensson, Kiousis, and Strömbäck 2015: 42). It could be that social media tools are just “extensions of traditional campaigns activities like fundraising, organizing volunteers, and identifying and turning out voters” (Towner and Dulio 2015: 73).

Donald Trump’s “amateurish yet authentic style” may signal a trend toward spontaneity and “deprofessionalization.” But even Trump “kept his followers at arm’s length and limited his engagement to retweeting selected tweets” by his supporters (Enli 2017: 59). Clever social media posts can humanize candidates in ways that a thirty-second TV spot cannot. Livestreaming campaign events add a sense of spontaneity. Yet campaigns are risk-averse. Managing the chaos of social media electioneering may discourage the serious innovation required to meaningfully empower users.

Key Terms

A/B testing: the controlled comparison of responses to one message or format (A) versus another (B). Used to assess which message or format is more effective.

fake news: false information that deceptively mimics the style and format of truthful journalism.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Why so you think campaigns tend to be risk averse in their social media outreach?

In what ways can candidates use social media platforms to empower supporters to campaign on their behalf?

Why is Facebook favored by campaigns over other social media platforms? How might campaigns more effectively use Snapchat or Instagram to reach young voters?

How concerned should we be about the spread of misinformation through social media? What is it about social media that is conducive to the distribution of “fake news”?

RECOMMENDED READINGS

Baldwin-Philippi, Jessica. 2017. “The Myths of Data-Driven Campaigning.” Political Communication 34, no. 4: 627–33.

The author of the book Using Technology, Building Democracy concludes that counter to conventional wisdom, neither the Trump nor the Clinton campaign was particularly innovative in their use of social media in 2016.

Guess, Andrew, Benjamin Lyons, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. 2018. Avoiding the Echo Chamber about Echo Chambers: Why Selective Exposure to Like-Minded Political News Is Less Prevalent Than You Think. Report published by the Knight Foundation.

As the title suggests, this review of academic research may allay concerns about the extent to which citizens are limiting their exposure to news that supports their predispositions. People are more vulnerable to “echo chambers” in their offline social networks than online, the authors conclude. Many people pay too little attention to political news, and those who do tend to have diverse information diets.

Kreiss, Daniel. 2016. Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

This book documents the Democratic Party’s embrace of technological advances in the wake of John Kerry’s loss to George W. Bush in 2004. Analyzes the work of 629 presidential campaign staffers from both parties from 2004 to 2012.

References

Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2: 211–36.

Allcott, Hunt, Matthew Gentzkow, and Chuan Yu. 2018. “Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media.” Unpublished manuscript.

173Anderson, Meg. 2016. “Hey, [Insert Name Here], Check Out These Campaign Fundraising Emails.” National Public Radio (July 3): https://www.npr.org/2016/07/03/484395568/hey-insert-name-here-check-out-these-campaign-fundraising-emails.

Anspach, Nicolas M. 2017. “The New Personal Influence: How Our Facebook Friends Influence the News We Read.” Political Communication 34, no, 4: 590–606.

Bakshy, Eytan, Solomon Messing, and Lada A. Adamic. 2015. “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook.” Science 348 (June 5): 1130–32.

Baldwin-Philippi, Jessica. 2015. Using Technology: Building Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2017. “The Myths of Data-Driven Campaigning.” Political Communication 34, no. 4: 627–33.

Barrett, Benjamin. 2018. “Where Does Snapchat Fit in 2018?” Campaigns & Elections (May 31): https://www.campaignsandelections.com/campaign-insider/where-does-snapchat-fit-in-2018.

Baumgartner, Jody C., and Jonathan S. Morris. 2010. “MyFaceTube Politics: Social Networking Web Sites and Political Engagement of Young Adults.” Social Science Computer Review 28, no. 1: 24–44.

Bessi, Alessandro, and Emilio Ferrara. 2016. “Social Bots Distort the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election Online Discussion.” First Monday 21 no. 11: ISSN 13960466. Available at: https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/7090/5653. Date accessed: March 20, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v21i11.7090.

Bode, Leticia. 2012. “Facebooking to the Polls: A Study of Online Social Networking and Political Behavior.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 9: 352–69.

———. 2016a. “Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media.” Mass Communication & Society 19: 24–48.

———. 2016b. “Pruning the News Feed: Unfriending and Unfollowing Political Content on Social Media.” Research and Politics (July–Sept.): 1–8.

Bode, Leticia, and Kajsa E. Dalrymple. 2016. “Politics in 140 Characters or Less: Campaign Communication, Network Interaction, and Political Participation on Twitter.” Journal of Political Marketing 15: 311–32.

Bond, Robert M., Christopher J. Fariss, Jason J. Jones, Adam D. I. Kramer, Cameron Marlow, Jamie E. Settle, and James H. Fowler. 2012. “A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Political Mobilization.” Nature 489: 295–98.

Broockman, David E., and Donald P. Green. 2014. “Do Online Advertisements Increase Political Candidates’ Name Recognition or Favorability? Evidence from Randomized Field Experiments.” Political Behavior 36: 263–89.

Bump, Philip. 2014. “How Facebook Plans to Become One of the Most Powerful Tools in olitics.” Washington Post Nov. 26: https://www.theawl.com/2014/11/in-the-trenches-of-the-facebook-election/.

Confessore, Nicholas, and Rachel Shorey. 2016. “Donald Trump, with Bare-Bones Campaign, Relies on G.O.P. for Vital Tasks.” New York Times 174(Aug. 21): https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/22/us/politics/donald-trump-fundraising.html?_r=0.

Conroy, Meredith, Jessica T. Feezell, and Mario Guerrero. 2012. “Facebook and Political Engagement: A Study of Online Political Group Membership and Offline Political Engagement.” Computers in Human Behavior 28: 1535–46.

Dimitrova, Daniela V., and Dianne G. Bystrom. 2017. “The Role of Social Media in the 2016 Iowa Caucuses.” Journal of Political Marketing, DOI: 10.1080/15377857.2017.1377141.

Dimitrova, Daniela V., Adam Shehata, Jesper Strömbäck, and Lars W. Nord. 2014. “The Effects of Digital Media on Political Knowledge and Participation in Election Campaigns: Evidence from Panel Data.” Communication Research 41, no. 1: 95–118.

DiResta, Renee, Kris Shaffer, Becky Ruppel., David Sullivan, Robert Matney, Ryan Fox, Jonathan Albright, and Ben Johnson 2018. “The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency.” https://www.newknowledge.com/articles/the-disinformation-report/.

Eady, Gregory, Jonathan Nagler, Andy Guess, Jan Zilinksy, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2019. “How Many People Live in Political Bubbles on Social Media? Evidence From Linked Survey and Twitter Data.” SAGE Open (Jan.–Mar.): 1–21.

Enli, Gunn. 2017. “Twitter as Arena for the Authentic Outsider: The Social Media Campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election.” European Journal of Communication 32, no. 1: 50–61.

Ferrara, Emilio. 2016. “How Twitter Bots Affected the US Presidential Campaign.” The Conversation (June 21): http://theconversation.com/how-twitter-bots-affected-the-us-presidential-campaign-68406.

Flaxman, Seth, Sharad Goel, and Justin M. Rao. 2016. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80: 298–320.

Fowler, Erika Franklin, Travis N. Ridout, and Michael M. Franz. 2016. “Political Advertising in 2016: The Presidential Election as Outlier?” The Forum 14, no. 4: 445–69.

Frier, Sarah. 2018. “Trump’s Campaign Said It Was Better at Facebook. Facebook Agrees.” Bloomberg (Apr. 3): https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-03/trump-s-campaign-said-it-was-better-at-facebook-facebook-agrees.

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Victor Garcia-Perdomo, and Shannon McGregor. 2015. “What Is Second Screening? Exploring Motivations of Second Screen Use and Its Effect on Online Political Participation.” Journal of Communication (July): 1–25.

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Ingrid Bachmann, Shih-Hsien Hsu, and Jennifer Brundidge. 2013. “Expressive Versus Consumptive Blog Use: Implications for Interpersonal Discussion and Political Participation.” International Journal of Communication 7: 1538–59.

Goel, Sharad, Winter Mason, and Duncan J. Watts. 2010. “Real and Perceived Attitude Agreement in Social Networks.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99, no. 4: 611–21.

Green, Joshua. 2012. “The Science behind Those Obama Campaign Emails.” Bloomberg (Nov. 29): https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-11-29/ the-science-behind-those-obama-campaign-e-mails.

175Grinberg, Nir, Kenneth Joseph, Lisa Friedland, Briony Swire-Thompson, and David Lazer. 2019. “Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 Presidential Election.” Science 363 (Jan. 25): 374–78.

Guess, Andrew, Benjamin Lyons, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. 2018. Avoiding the Echo Chamber about Echo Chambers: Why Selective Exposure to Like-Minded Political News Is Less Prevalent Than You Think. Report published by the Knight Foundation.

Guess, Andrew, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua Tucker. 2019. “Less Than You Think: Prevalence and Predictors of Fake News Dissemination on Facebook.” Science Advances 5 (Jan. 9): 1–8.

Guess, Andrew, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. 2018. “Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign.” Unpublished manuscript.

Gunther, Richard, Paul A. Beck, and Erik C. Nisbet. n.d. “Fake News May Have Contributed to Trump’s 2016 Victory.” Unpublished manuscript.

Hamby, Peter. 2013. “Did Twitter Kill the Boys on the Bus? Searching for a Better Way to Cover a Campaign.” Discussion Paper #D-80. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy.

Harvey, Del, and Yoel Roth. 2018. “An Update on Our Elections Integrity Work.” Oct. 1: https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/company/2018/an-update-on-our-elections-integrity-work.html.

Heimlich, Russell. 2010. “Email vs. Social Networks.” Pew Research Center (Sept. 13): https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2010/09/13/email-vs-social-networks/.

Hohmann, James. 2018. “The Daily 202: Russian Efforts to Manipulate African Americans Show Sophistication of Disinformation Campaigns.” Washington Post (Dec. 17): https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/ daily-202/2018/12/17/daily-202-russian-efforts-to-manipulate-african-americans-show-sophistication-of-disinformation-campaign/ 5c1739291b326b2d6629d4c6/.

Katz, Elihu, and Paul F. Lazarsfeld. 1955. Personal Influence. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Kim, Young Mie, Jordan Hsu, David Neiman, Colin Kou, Levi Bankston, Soo Yun Kim, Richard Heinrich, Robyn Baragwanath, and Garvesh Raskutti. 2018. “The Stealth Media? Groups and Targets behind Divisive Issue Campaigns on Facebook.” Political Communication 35, no. 4: 515–41.

Korecki, Natasha. 2019. “‘Sustained and Ongoing’ Disinformation Assault Targets Dem Presidential Candidates.” Politico (Feb. 20): https://www.politico.com/story/2019/02/20/2020-candidates-social-media-attack-1176018?fbclid=IwAR169iVYwr62UHsI6XWkL-SBPhgEcZpA8SSR97WPpDbr-gn1gULfE_igJSA.

Kreiss, Daniel. 2016. Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kreiss, Daniel, Regina G. Lawrence, and Shannon C. McGregor. 2018. “In Their Own Words: Political Practitioner Accounts of Candidates, Audiences, Affordances, Genres, and Timing in Strategic Social Media Use.” Political Communication 35: 8–31.

Kreiss, Daniel, and Shannon C. McGregor. 2018. “Technology Firms Shape Political Communication: The Work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and 176Google with Campaigns during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Cycle.” Political Communication 35, no. 2: 155–77.

Krieg, Gregory. 2016. “GOP Senate Group Deletes Tweet about Double Amputee Pol ‘Not Standing Up for Our Veterans’.” CNN (Mar. 8): https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/08/politics/tammy-duckworth-nrsc-tweet-deleted-veterans/.

Lapowsky, Issie. 2016. “Here’s How Facebook Actually Won Trump the Presidency.” Wired (Nov. 15): https://www.wired.com/2016/11/facebook-won-trump-election-not-just-fake-news/.

Lazer, David M. J., Matthew A. Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J. Berinsky, Kelly M. Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J. Metzger, Brendan Nyhan, Gordon Pennycook, David Rothschild, Michael Schudson, Steven A. Sloman, Cass R. Sunstein, Emily A. Thorson, Duncan J. Watts, and Jonathan L. Zittrain. 2018. “The Science of Fake News.” Science 359, no. 6380: 1094–96.

McCoy, Terrence. 2016. “For the ‘New Yellow Journalists,’ Opportunity Comes in Clicks and Bucks.” Washington Post (Nov. 20): https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/for-the-new-yellow-journalists-opportunity-comes-in-clicks-and-bucks/2016/11/20/d58d036c-adbf-11e6-8b45-f8e493f06fcd_story.html?utm_term=.73210f389c2f.

Messing, Solomon, and Sean J. Westwood. 2014. “Selective Exposure in the Age of Social Media: Endorsements Trump Partisan Source Affiliation When Selecting News Online.” Communication Research 41, no. 8: 1042–63.

Mosseri, Adam. 2017. “Working to Stop Misinformation and False News.” Apr. 7: https://www.facebook.com/facebookmedia/blog/working-to-stop-misinformation-and-false-news.

Nelson, Jacob L., and James G. Webster. 2017. “The Myth of Partisan Selective Exposure: A Portrait of the Online Political News Audience.” Social Media + Society (July-Sept.): 1–13.

Pariser, Eli. 2011. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. New York: Penguin Books.

Patterson, Thomas. 2016. News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters. A report published by the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy in conjunction with Media Tenor (December).

Pearce, Adam. 2016. “Trump Has Spent a Fraction of What Clinton Has on Ads.” New York Times (Oct. 21): https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/10/21/us/elections/television-ads.html.

Persily, Nathaniel. 2017. “Can Democracy Survive the Internet?” Journal of Democracy 28, no. 2: 63–76.

Pew Research Center. 2016. “Election 2016: Campaigns as a Direct Source of News.” July 18: http://www.journalism.org/2016/07/18/election-2016-campaigns-as-a-direct-source-of-news/.

Schill, Dan, and Rita Kirk. 2015. “Issue Debates in 140 Characters: Online Talk Surrounding the 2012 Debates.” In Presidential Campaigning and Social Media: An Analysis of the 2012 Campaign. Edited by John Allen Hendricks and Dan Schill, 198–218. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shearer, Elisa, and Katerina Eva Matsa. 2018. “News Use across Social Media Platforms 2018.” Pew Research Center, Sept. 10.

177Silver, Nate. 2017. “The Comey Letter Probably Cost Clinton the Election.” FiveThirtyEight (May 3): https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-comey-letter-probably-cost-clinton-the-election/.

Silverman, Craig. 2016. “This Analysis Shows How Viral Fake Election News Outperformed Real News on Facebook.” Buzzfeed (Nov. 16): https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook#.va37DQajn.

Silverman, Craig, and Lawrence Alexander. 2016. “How Teens in the Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters with Fake News.” Buzzfeed (Nov. 3): https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo#.hcRNEk6Ox.

Silverman, Craig, J. Lester Feder, Saska Cvetkovska, and Aubrey Belford. 2018. “Macedonia’s Pro-Trump Fake News Industry Had American Links, and Is Under Investigation for Possible Russia Ties.” Buzzfeed (July 18): https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/american-conservatives-fake-news-macedonia-paris-wade-libert.

Skoric, Marko M., Qinfeng Zhu, Debbie Goh, and Natalie Pang. 2016. “Social Media and Citizen Engagement: A Meta-analytic Review.” New Media & Society 18, no. 9: 1817–39.

Smith, Aaron, and Monica Anderson. 2018. “Social Media Use in 2018.” Pew Research Center, Mar. 1.

Sunstein, Cass. 2009. Republic.com 2.0. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Svensson, Emma, Spiro Kiousis, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2015. “Creating a Win-Win Situation? Relationship Cultivation and the Use of Social Media in the 2012 Election.” In Presidential Campaigning and Social Media: An Analysis of the 2012 Campaign. Edited by John Allen Hendricks and Dan Schill, 28–43. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thorson, Kjerstin, Emily K. Vrega, and Neta Kliger-Vilenchik. 2015. “Don’t Push Your Opinions on Me: Young Citizens and Political Etiquette on Facebook.” In Presidential Campaigning and Social Media: An Analysis of the 2012 Campaign. Edited by John Allen Hendricks and Dan Schill, 74–93. New York: Oxford University Press.

Towner, Terri L., and David A. Dulio. 2015. “Technology Takeover? Campaign Learning during the 2012 Presidential Election.” In Presidential Campaigning and Social Media: An Analysis of the 2012 Campaign. Edited by John Allen Hendricks and Dan Schill, 58–73. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valenzuela, Sebastián, Namsu Park, and Kerk F. Kee. 2009. “Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students’ Life Satisfaction, Trust, and Participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, no. 4: 875–901.

Vitak, Jessica, Paul Zube, Andrew Smock, Caleb T. Carr, Nicole Ellison, and Cliff Lampe. 2011. “It’s Complicated: Facebook Users’ Political Participation in the 2008 Election.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14, no. 3: 1–17.

Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. 2018. “The Spread of True and False News Online.” Science 359 (Mar. 9): 1146–51.