One of the things that happens, which people rarely want to admit, is that when a parent or a spouse dies there is, along with the sadness and the ache of loss, a liberating kind of freedom. For the rest of one’s life, the question becomes how one deals with that freedom.

My dad’s death did not unmoor me, it only made me aware that I had to be a bit more vigilant in my life choices since I had lost 50 percent of the moral overview I greatly valued.

My brother felt true sorrow. But he also could now throw off what he felt to be a somewhat oppressive and restraining yoke. He was free to do what he wanted to do, not what he felt my father wanted him to do.

My mom grieved and lived with a layer of sadness that never truly left her—but she also leapt into an independent life where she was now her own key decision maker.

She and I grew closer. Our relationship became one of deep affection and mutual respect and we spent even more time together because we wanted to, not because we had to. In the same way she had once assumed a part-time father role, playing football and baseball with me when I was young, now she took up the mantle of moral checkpoint. She was far less vocal than my dad; rather than thundering, she tended to raise an eyebrow or perhaps say, “Is that the smart thing to do?” But her perspective was always clear and pointed.

Everyone told my mom not to make any rash decisions the first year of widowhood and she didn’t. She remained in the large house, spent much time working in the kitchen at Spago (her preferred safe haven), wrote new cookbooks, did some teaching. But things changed around her. Some of her friends—at least people she thought of as friends—stopped calling. Mostly they were couples who valued the male part of the coupledom more than the female. But some were women, also widowed; many of them also stopped calling. I told my mom that some people simply didn’t know how to deal with death. It made them uncomfortable and so they retreated. My mother, in full “animal” mode, had one response: “Fuck ’em.” She never forgave those who carelessly or deliberately hurt her.

Increasingly, she struck out on her own. Some friends were carryovers—those who demonstrated that they were worth carrying over; my mom made it her choice rather than theirs—and many were new, people who met and valued my mother as an individual. Most of these newbies were connected to food: chefs or chefs’ agents or restaurant owners or people selling cookware. Sometimes they were just food lovers: students of hers or regulars at Spago. My mom believed that an appreciation of food was a window into character and that became a shorthand method she used to open herself up to trust people.

She thought seriously about starting her own business—a cookie store; she made superb and unique cookies, thick and chewy as mini-brownies. However, the friend she was going to partner with died suddenly, in her sleep, and that put a damper on the new business. To a degree, my mom spent this period drifting. But this was the period in which she was allowing herself to drift, even being urged to drift.

Two years after my dad’s death, a major earthquake hit L.A. My mom’s house was up in the hills, and a big chunk of her hillside above Mulholland Drive disappeared in moments. She had no electricity for a week or two, which frightened her and made her feel trapped and vulnerable. She decided it was time to sell the house, which she did quickly, and she moved to an apartment that was walking distance from Spago. It was her first attempt to stop the drift.

She began to spend time away from Los Angeles, still mourning my dad but also appreciating her freedom. The first summer she was on her own, she rented a house in Sag Harbor, the town where I have a weekend house. It was great to have her there. She gave weekly cooking lessons to my friends and me: we learned how to make garlic soup and pie dough, and this was the first time I ever saw how to properly clean a mushroom by peeling off the top skin rather than trying to wash the pesky little things. Janis and I would also wake up in the morning and there would be fresh ginger scones that my mom had baked, sitting on the kitchen table, along with a jar of freshly made strawberry jam. It was a summer of homemade morning muffins and group dinners that honed my cooking skills and my palate and helped my mom come to stand on her own and begin to make peace with her new existence.

My mom had always loved to travel, and more and more she began to indulge her adventurous streak. For her first big trip, she went with her niece Beth to New Guinea, where they walked with natives in the jungle and slept in straw huts. In full Auntie Mame mode, and for some reason I could never quite fathom, she also bought native-made penis sheaths as gifts for many of her friends back home. After that, mostly with Beth, occasionally with her sister Belle or her sister Lil, over the next decade or so my mom went to London (several times), France, Hong Kong, Thailand, Taiwan, Bali, Prague, Budapest, Vienna, Salzburg, Kenya, Tanzania, the Netherlands, Morocco, Tuscany, Rome, Sicily, Russia, Poland, Germany, Spain, and southern India. I heard much about the food in all of those places (India might have been her favorite eating trip, although I think she was ready for a change by the time she and Beth returned home). And over the years, it never failed to tickle her when I would say, “I’d love to go to such-and-such” and she’d wave her hand dismissively and say, “Been there.” She was proud of her adventurous spirit and enjoyed gloating about it.

After two years of L.A. apartment living, my mom decided it was time for another change. Despite the fact that it meant leaving many of her friends behind, she packed up and moved to New York. I found her a great apartment in the Village but she mysteriously resisted the idea of living downtown. She wouldn’t explain her stubbornness but she moved into an apartment on the Upper East Side and slid into city living as if she hadn’t been gone for thirty years.

New York City food and restaurant life was thriving in the early nineties. Many of my mother’s L.A. disciples—waiters who were now restaurant managers, managers who were now owners, sous-chefs who were now kings of their own castles—had migrated east. It didn’t take long for my mom to be as revered in the New York food scene as she was in Los Angeles.

One afternoon I came back from a business trip to London. I’d been gone for a couple of weeks and as I was going through my stacks of mail, I saw a postcard that announced the opening of a new restaurant on my block, two or three doors down from my apartment. It was called Blue Hill and the announcement proclaimed that they were open for a few weeks to just “friends and family.” They made it clear that “family” included anyone who lived near the place. I immediately called my mom and said she should come downtown around seven thirty and we’d go try out the new restaurant. Without hesitating, she agreed.

After we’d had a martini, a bottle of wine, and the incredibly delicious fixed tasting menu—that was all they were serving during their six-week-long trial opening, so they could perfect both the cooking and the service—I told my mom I was going to go introduce myself to and praise the chef.

I made my way to the kitchen, introduced myself to the chef, who also happened to be the owner, and whose name was Dan Barber (now considered one of the major, most influential chefs in New York—Blue Hill is where Michelle Obama insisted she and her husband go on their first dinner date after he was elected president). We shook hands. I said that I practically lived next door, told him how great the dinner was and that I was his new best customer, and then told him my name.

He cocked his head and said, “Gethers? Are you any relation to Judy?”

I nodded and said that she was my mom.

His eyes widened and he said, “She’s my idol.”

I said, “Well, she’s had a martini and some wine, so she’s propped up by the front door, but I can go back and get her, if you want.”

He very much wanted that. When my mom had made her way back to the kitchen, Dan told her that they’d met before—he had been on the line at Nancy Silverton and Mark Peel’s L.A. restaurant, Campanile—and he said that my mom’s Italian cookbook had been one of the things that inspired him to become a chef. He also talked about how everyone revered her in the L.A. cooking scene. My mom looked embarrassed—but thrilled—and told him how wonderful our meal was. Then she headed uptown and I went back to my apartment, still somewhat surprised by and pondering the fact that my mother was a great chef’s idol.

That was not an isolated incident when going out and about with my mom. We’d go to one of Danny Meyer’s restaurants and the server would bring a complimentary appetizer to the table, announcing, “Danny says you’re the queen of the cooking world and he wants you to try this.” Michael McCarty owns the eponymous Michael’s on East 55th Street, the hot publishing and TV spot for lunch in midtown. I’d go in there and Michael, who goes back to the days of the Ma Cuisine cooking school, would come over and say, “Please bring your mom in! I love her! She’s like my own mom!” She could get reservations instantly in restaurants that wouldn’t take me for three weeks. Chefs would try out new dishes for her to taste. Sometimes meals were free or the final amount was half of what it should have been. My mom dismissed all this treatment. But she loved it. And although she never would admit it, she understood that she deserved it.

One day, my mother told me she wanted to go to Shopsin’s. Kenny Shopsin, whom I’ve known for forty years, is legendary in New York City for many reasons: because he is one of the great short-order cooks of all time, because his various restaurants have all been tiny but he never has had less than a five-hundred-item menu, because he creates unique and extraordinary dishes like mac-and-cheese pancakes and an egg dish called Blisters on My Sisters. But his fame has largely spread because he terrifies his customers. He won’t seat more than four people at a table. If you try to circumvent this rule and, say, sit with two of your friends at one table for three while two other friends sit at another, Kenny will throw you out of the restaurant. If you try to order a standard dish—one you’ve never tasted—but ask for him to, say, do it without the onions, he’ll throw you out of the restaurant. If you just seem like the kind of person he doesn’t like, he’ll throw you out of the restaurant. Kenny’s motto is “The customer is almost never right.” I love Kenny Shopsin.

Kenny is quite a profound person, but without question he is also the most profane human being I’ve ever met—another reason he can make strong customers cower in fear. He cannot get through a complete sentence without using several nine- and ten-letter words that would make a sailor blush. He will say anything to anyone and not give it a second thought. So the idea of putting him together with my mom made me tremble just slightly. But I promised her we’d go. Before we went, however, I called Kenny.

“My mom’s eighty-five years old,” I said. “So try to be on your best behavior.”

His comeback was: “I’m always on my best behavior.”

True enough. That’s what I was afraid of.

I took my mom down to Shopsin’s and Kenny came over to join us. He knew my mom’s food background and they discussed that for a bit. He was charming and friendly. I relaxed. Then my mom said, innocently, that she’d had dinner the night before at Daniel, Daniel Boulud’s restaurant, which many people think is the best restaurant in New York. Kenny nodded politely and said, “Do you want to hear my theory about Daniel Boulud?”

I wanted to say, “No,” but I was too late.

“I think he’s a great chef. I don’t have any argument with that. But my palate isn’t nearly good enough to appreciate how fine he is. And I think most people are like that. They don’t really understand how good his food is. They just go to his restaurants because they’re famous, and everyone tells them they’re great, and people are sheep, so they go to the place that has Michelin stars and they tell everyone they’ve eaten there. But they don’t really have a clue about the food.” My mom nodded, not disagreeing, and then Kenny made his final point. “It’s like fucking a five-hundred-dollar hooker with a ten-cent dick, you know what I mean?”

There was a decent pause. I worked up the nerve to look at my mom. She was staring blankly ahead. Then she nodded and said, “Yes, I know exactly what you mean.”

* * *

I THINK THE main reason my mother came back to NYC was to be near her sister Belle. The two of them had gotten even closer after my dad died. They enjoyed each other’s company, could reveal things to each other that were deeply private and personal, and had fun together. My mother, although the younger sister, felt a certain pride that she had helped lift Belle out of the narrow life she had led for many years—bringing her into the more sophisticated world in which my mom thrived—and she liked the idea that, having moved back to Manhattan, she could keep Belle on a closer tether to that world. But soon after my mom’s return, Belle was diagnosed with cancer and a year or so later, she died at the age of eighty-two.

I was asked to speak at her funeral and, although I humiliated myself by being unable to get through more than three or four consecutive words of the eulogy without bawling like a baby, I did manage to make one thought clear: Belle was a better, kinder, and more interesting person at eighty than she had been at forty.

My most rigid theory about people is that as we age we become more and more like our true selves. At first I thought that Belle had broken that mold. Then I realized she hadn’t. She had fought for decades to tamp down her true self—partly out of familial duty, partly out of fear, partly because that’s all she knew how to do. But with my parents’ help—or more likely, with my parents as a kind of escape hatch—the older she got, the more she allowed that true self to emerge. By the time she died she was one of the funniest, sharpest, most interesting, most moral people I knew.

Belle’s death was another blow to my mom, but she continued to amaze me with her resiliency. In Belle’s absence, she grew closer to her sister Lil. As did I. Lil was as steely as my mom and Belle, possibly even more so, without the softer side. She was tough, tough, tough. But very smart and fascinating. She would tell stories about living in California as a young girl pre–World War I and talk about going to speakeasies in New York City (and drinking the psychedelic absinthe) during Prohibition. Well into her nineties, she could still tell you the exact address of her favorite 1920s speakeasy.

My mom also began traveling even more often. One of the places she now went, along with her niece Beth and one of my mom’s oldest friends, Esther (Esther had been married to Albert, the frustrated garment exec/Dixieland drummer who played at Arthur’s in the West Village), was a restaurant in Sicily that had become near and dear to my heart: Gangivecchio.

In 1991, Janis and Norton the cat and I spent a week traveling around Sicily. Before we departed, we read a New York Times article by Mary Taylor Simeti about a place called Tenuta Gangivecchio. The intriguing elements in the article were: this was the best restaurant in Sicily, it was housed in a thirteenth-century abbey, and it was nearly impossible to find. Eating at Gangivecchio immediately became my quixotic quest.

Amazingly enough, considering my total lack of any sense of direction, we found Gangivecchio and had the best lunch imaginable: veal rollatini, pasta with five-nut pesto sauce, and, most memorably, small turnovers fried in lard and stuffed with warm lemon cream. Three days later we were in Agrigento and instead of spending the day among the magnificent Greek temples, I insisted we make the three-hour drive back to Gangivecchio so we could repeat our lunch. It was even better the second time around. The food was just as extraordinary but we also sat and talked with Wanda and Giovanna Tornabene, the mother-and-daughter team who owned the abbey and ran the restaurant. Wanda didn’t speak a word of English, although she seemed to understand everything we said, and Giovanna spoke a lovely, fractured English that made me swoon. She was also brilliant, charming, and captivating. Wanda was mostly scary. She was like my aunt Belle on steroids—if Belle also had a shotgun and a history of fending off local mafiosi trying to collect protection money.

Wanda’s and Giovanna’s lives changed quite a bit as the result of our second lunch. I convinced them to write a cookbook, which they did, and then they wrote two more. Their first two books won James Beard Awards. They promoted the books throughout America, turned their stables into a lovely nine-room inn, and, as a result of their publishing success and ensuing publicity, people started to come from all over the world to eat and spend a few days there. My life changed as well.

I bought the renovated 150-year-old stone caretaker’s cottage on the abbey’s property after the six weeks I spent holing up there to finish writing my novel. My daily routine for those six weeks was: wake up early and go for a run in the mountains. Upon my return, Pepe—the man who did everything imaginable for the Tornabenes—would knock on my door and say one of the three phrases he knew in English, “Breakfast is ready.” I’d have some strong espresso and fresh fruit, then write until one o’clock, at which time Pepe would again knock on my door and utter phrase number two in his English vocabulary: “Lunch is ready.” After lunch, I’d write for a few more hours, then exercise like a lunatic because I knew what was coming, and then at around eight o’clock, I’d hear the final words of Pepe’s trilogy: “Dinner is ready.” I would then go to the abbey and, night after night, eat more than a pound of pasta. My pasta eating became somewhat legendary. Years later a friend stayed at the cottage, came back to New York and incredulously asked, “Did you really eat over a pound of pasta every night?” At first I denied it but, under pressure, was forced to capitulate. It was on the final day of that six-week writing and pasta-eating jag that I called Janis, who was in New York, and we agreed to buy the cottage.

My mom, Beth, and Esther spent a few days eating and cooking with Wanda and Giovanna. My mom fell in love with the place, as I had—the rusticity and occasional lack of heat and hot water in the cottage didn’t faze her one bit—and she came back raving about one pasta dish in particular: Buccatini with Cauliflower, Pine Nuts, Currants, Anchovies, and Saffron. My mom was a pasta lover and she thought this was as good as it got.

I don’t use this word lightly or flippantly, but my mom, as she approached eighty, was “cool.” And I don’t say this only because she was willing to rough it in the Sicilian cottage. She understood instinctively why, at the age of thirty-eight, I quit my relatively high-powered publishing job and took off for Provence. She appreciated nonconformity, didn’t place much value on material possessions, didn’t care what anyone’s net worth was. She had long outgrown her Pollyanna-ish view of the world yet, with a remarkable lack of cynicism, saw life for what it was and people for who they were. She inherently understood people’s actions. She knew immediately when someone was bullshitting her—a word she came to use more and more; she loved saying “bullshit”—and she had a real sense of whether someone was fake or genuine. She had an unerring radar when it came to assessing other people’s motives. I think it was because hers were usually pure.

She had one absolute blind spot, to which she was entitled: her grandson. She never said no to Morgan, the product of my brother’s second marriage. My mom loved him without equivocation and with no strings attached. He understood that from a very young age, grew to appreciate it and depend on it, and he never abused that love or took advantage of it. He was unfailingly polite to her, which was particularly sweet, and he not only took great interest in the things that interested her, he gently forced her to take interest in the minutiae of his own life. She was always attracted to young people and the immersion in his world and interests helped keep her young. My nephew—as I have told him many times—has done a lot of dumb things and things of which I’ve disapproved, but he never, not once, treated his grandma with anything but genuine love and respect.

Part of my mom’s blinding love for Morgan was an extension of my dad’s near-insane and manic captivation with him when Morgan was just a baby, a way of keeping my dad’s feelings and wishes alive. But my mom’s love was real and heartfelt, no question about it—and it stayed that way even as she began to also disapprove of some of his choices. But disapproval had nothing to do with how much she loved him and how much she supported his choices.

His parents divorced when he was young. During Morgan’s teenage years my mother, approaching eighty, became his rock, the one thing he could count on and know would never disappoint him.

And when Morgan was twelve or thirteen years old, he became very interested in food and cooking. In college he took cooking lessons. My mom brought him to good restaurants on his New York visits and kvelled when he experimented with tastes and fearlessly tried the unknown. Morgan has inherent taste when it comes to food.

He has my mom’s taste.

* * *

ON OCTOBER 5, 2008, a Sunday, a couple of months after my mother’s eighty-sixth birthday, she, Janis, and I had lunch with some of my cousins (on my dad’s side). My mom was in good spirits. She loved and enjoyed her nieces and nephews and the feelings were mutual. There were also plenty of great-nieces and great-nephews and my mom liked keeping tabs on them and knowing that she was, to a degree, a part of their lives.

After lunch, we had our usual taxi argument. The way it worked is that I’d hail a cab and my mother would insist that Janis and I take the first one. Even when it was snowing or pouring rain. Once when it was so windy we thought she might blow away if we didn’t hold on to her arms and keep her feet on the ground. We’d explain that she was in her eighties, somewhat frail, and that she should take the first cab that came by. She’d shake her head and insist. I’d roll my eyes and insist back. She’d insist more vehemently. Finally, Janis would wind up saying, “Judy, get in the damn cab!” On this particular Sunday, we put her in the taxi around three in the afternoon and she headed uptown.

Around one o’clock the next afternoon, I got a call from my mother’s close friend Jan (not to be confused with Janis). Even though she was thirty or so years younger than my mom, they were inseparable. Jan checked in with her every day and they saw each other constantly. On the phone, Jan told me the following:

Knowing my mom was a psychotically early riser (she refused to ever stay in bed much past six a.m.), she called my mother’s apartment around eight. No answer. She assumed my mother was already out and around. By eleven in the morning, she was concerned that they hadn’t yet connected, so she went over to my mom’s building. The doormen let her up to the tenth floor and, stepping out of the elevator, she saw that my mom’s newspaper was still in the hallway outside the door. She knew something had to be wrong—there was no way my mother could still be in bed at that hour. Jan had a key and let herself in. She found my mother on the floor of her den, unmoving, unable to speak, but alive.

Her bed had not been slept in so doctors later estimated that my mother had her stroke sometime between three thirty and nine p.m., which is when she might have normally turned in for the night, or at least gotten under the covers to watch TV. My mom did have one of those “Help, I’ve fallen and can’t get up” things that she wore at home since she had her first stroke, but this attack came so suddenly and violently that she hadn’t had time to press the button. Once down, she was paralyzed and couldn’t move to reach it. She had been alone, overcome by the stroke, unable to budge, for at least fourteen hours, perhaps as many as nineteen. To recover from a stroke of this magnitude, the medical consensus is that the stroke victim must be discovered and treated within an hour of the attack, two at the most.

My mother was rushed by ambulance to Lenox Hill Hospital—conveniently one block from her apartment—and taken to the emergency room. I left my office, frantically hailed a cab, and met Jan there. Although she wasn’t related and thus met some resistance from the hospital staff, she had refused to leave my mother’s side.

My mother spent much of the afternoon lying on a mobile cot in the ER hallway. They were waiting for the right doctor; they were waiting for the MRI to become available; they were waiting to get her in the line for a CAT scan. She’d finally get one scan taken, then back she went to the hallway. No matter how much I yelled, insisted, or even tried to bribe, my mom spent at least eight more hours strapped to the gurney in the hall. Somewhere around nine p.m., she was finally under proper doctor’s care and taken for more tests.

Jan and I went to a restaurant a block from the hospital. All I remember is that it was a French bistro and we both downed a decent amount of wine and neither of us ate much. Around ten o’clock, we went back to the hospital. It was difficult to attract anyone’s attention or to get answers about my mother’s condition. One of the attendants was absorbed in Monday Night Football on the TV at his desk and was loath to look away or respond to my badgering. Around midnight, we were told that she would not regain consciousness that night and there was no real reason for us to stick around. Quite a few of those hours at the hospital are blurry in my memory. I know that Janis joined me for a good part of the time, as did Beth. I know that it didn’t occur to me to call or e-mail anyone else to reveal what was happening. I was able to focus on only one thing.

The next morning, I was back at the hospital, first thing. One of the doctors came over to tell me that there was too much swelling for them to be absolutely certain, but it looked like the stroke had been very powerful and had hit my mom in the worst possible spot, the dead center of her brain. As a result, it was likely that she would have locked-in syndrome—she would not be able to speak or move a muscle for the rest of her life.

The doctor told me I could see her and I found her in a curtained-off cubicle in the ER—she still had not been admitted to a real room in the real hospital. Her skin color was a faded and pasty green, her hair was sweat soaked and matted to her head. She looked to me as if she had died several hours ago. But when I stepped in, her eyes opened.

“Lookin’ good, Mom,” I said. And she rolled her eyes.

That roll said, “Don’t be a smart ass.” Her eyes also said: “How did this happen?” They showed humor and defiance. And utter exhaustion.

The next day, finally in a real room, she moved her left arm. The left arm they said would never move. Her finger crooked and made a slight motion that I should come closer. The finger they said would never move. And then she spoke, which they also said would never again happen. The words she spoke were: “What a lot of shit.”

The next day my mother began physical and speech therapy—much to the shock of everyone in the hospital. They said that it was impossible for my mother to be doing what she was doing. I shrugged. I’d seen it before. The physical aspect was arduous and extraordinarily difficult. Straightening her head, aligning it with her spine, took a Herculean effort. Speech therapy was frustrating agony for my mother and fascinating for me. Her speech therapist was remarkably patient and gentle. She would start by asking my mom to fill in the blanks in a sentence. She would say, “I went to the store to get some ________ for my cereal.” And my mother would say, “Cows.” I couldn’t help it, I’d laugh, and so would the therapist and so would my mom. But the therapist would explain that it was a good answer because it was close enough to one real and obvious answer—milk, and cows produced milk—to show that the brain functions were working.

Other sentences my mom tried to complete:

“For breakfast I had a glass of orange … beds.”

“Two plus two equals … two.” My mom immediately knew this answer was wrong, screwed up her face, nodded calmly, and gave what she was certain was the right answer: “One.”

“Peanut butter and … red paint.”

“All I want for Christmas are my two front … elephants.”

Because I had explained a bit about my mother’s past to the therapist, many of her questions were geared around food. Each time the therapist could explain the logic behind my mother’s incorrect answers. She spent hours and hours explaining them to my mom, too, so she could slowly begin to untangle the twisted neurons misdirecting her language traffic.

Ten days after my mom’s stroke, I was told that she had to leave the hospital in three days. I panicked.

“She can’t move,” I said. “She can barely speak. How can she go back to her apartment? What the hell am I supposed to do?”

The hospital social worker sat down with me. Reassuring and helpful, she explained that my mom needed to be moved to a rehabilitation center. Hopefully, after rehab she’d be able to return to her own home, with the proper live-in care. I was warned that I shouldn’t count on that, however. The doctors suspected that she would be forced to live in an institution for the rest of her life.

She could not go back to the Rusk Institute, where she’d gone after her first stroke, because she was not advanced enough in her recovery to fit into their rigorous program. So I began scouring the city for nursing homes. The first one I went to was just a few blocks from my apartment—convenient from a travel time perspective if nothing else. And believe me, it was nothing else. Gorgeous on the outside, a landmark Greenwich Village building, inside it was a cross between the asylum in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the World War II Japanese POW camp in The Bridge on the River Kwai. I saw roaches scuttling around and the place was absolutely filthy. The guide showed me one room, the size of the smallest dorm room at the worst college imaginable. In it were two beds and one nightstand—there wasn’t room for more. In one of the rooms was a person—I couldn’t tell if it was a man or woman, and I don’t think he or she could, either—who was hooked up to a few machines and wasn’t moving. The other bed was empty. Indicating the body in the bed, the guide said, “This is Mrs. Johnson. She’ll be a very good roommate for your mom because she’s very quiet.”

“That’s because I’m pretty sure she’s dead,” I said.

I got out of there within seconds.

I looked at a few others and all I could think of was my mother saying to me, a few years ago, “If I ever wind up in a home with nothing but old, sick people, just smother me with a pillow and kill me.”

After my tour of rehab homes, I was almost to the point of deciding that that was a reasonable and decent course of action.

Then my mother’s wonderful doctor came through. He used his pull to get her into a lovely, humane rehab center, Amsterdam Nursing Home, on 114th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. I spent a lot of time there over the next few weeks and, if you’re interested in some New York City sightseeing pointers, a couple of blocks from her rehab joint was the real-life diner they used as the George/Jerry/Kramer/Elaine hangout in Seinfeld. I had a lot of coffee and quick meals there and it always made me grin to step inside. I’m big on silver linings, especially if they involve pancakes or western omelets.

The day I learned that my mother could be moved into the Amsterdam home, I called my brother, who was living in France, to tell him what had happened. Eric called Morgan to fill him in and a few days later, both of them flew into New York.

My mom was thrilled to see them. Morgan stayed two or three days and my mom perked up every second he was around her. Same for Eric. He hung out at the rehab place, spent a lot of time talking to her and trying to do whatever could be done to help her. He said later that it was the first real quality time that he and my mom had spent together in years.

Now I began spreading the word, telling people what had occurred. My mom had an enormous and varied circle of friends, so Janis, who was amazing during this entire period, began sending out mass e-mails about the events of the past couple of weeks, regularly giving updates on my mom’s condition. The first one gave a thorough overview and assured everyone that my mom was making progress. Then, over the next few weeks, there would be helpful tidbits: “Judy got out of bed and into a wheelchair!” “Judy moved her right hand!” “Great news: Judy took a shower and washed her hair and she looks beautiful!”

Everyone was, of course, concerned, and everyone was understanding and helpful, knowing just when to intrude and participate and when to step back.

Well, almost everyone. One of my mother’s friends in Los Angeles called one night to find out what was happening and how my mother was doing. This was early on in the recovery process, so I was particularly stressed. I happened to be at the hospital, in my mom’s room, when this woman called. My mom obviously couldn’t talk on the phone, so I explained to her friend how we were handling the situation and I said that an e-mail would go out every few days for a while and then as often as there was something to report. The woman said, “That’s not good enough.” I explained that was the best that could be done because there were a lot of people who were concerned and with whom we needed to communicate. She then said, “No. I want you to call me every day to tell me exactly what’s happening.” I said, “Excuse me?” And she repeated it: “I want you to call me every day!” I guess she caught me at a somewhat fragile moment because my immediate and exact response was, “I don’t think you do want that … because if I did, every single day, I’d tell you to go fuck yourself!” And I hung up the phone.

My mother, just a little startled, muttered something, which I understood to be, “Who was that?” When I told her, and repeated the conversation, my mother laughed for what must have been five minutes. Then she did her best to say something else, which I finally figured out was an admonishing, “You’re terrible.” Then she started laughing again.

After my mom had been in the nursing home for a week or so, Wolfgang called me to say he was coming to New York and would bring food to my mom. I told him that she was relearning how to eat. At first she could only sip liquids, and very slowly. Over the past few days she had progressed to soft food that didn’t require real chewing. Wolf showed up two days later—it was a surprise to my mom—with a huge bowl of mushroom risotto. My mother was not the only one who was ecstatic. The entire nursing staff almost fainted when Wolfgang Puck—the one from the Home Shopping Network!—stepped out of the elevator to bring Mrs. Gethers food. She was golden from that day on.

Wolf’s visit gave my mom a great boost. He was the first non-family member she allowed in to see her—my friend Paul and his wife Laurie counted as family—and eating his risotto made her realize that things could be normal again. Or reasonably so.

It wasn’t long after Wolf’s cameo that my mom spoke her first fully thought-out and complete sentence to me since she’d had her stroke: “Get me out of here!”

From that point on, the will of steel kicked in big time. She ate, she spoke better, she moved better. She walked, taking tentative baby steps, with a lot of aid. Because she was determined to get the hell out of there, she was an ideal patient, pushing her therapists to work her harder, doing everything by the rules except for one thing: she refused to take her meals in the common room with other patients. The nurses told me they thought it would be good for her to interact with other people. I told this to my mom.

“No,” she said. “Don’t like old, sick people.”

“Mom … you’re kind of an old, sick person yourself. So maybe it’s not such a bad idea.”

“I’m … getting … out … of … here.”

And she did. She didn’t make my favorite yearly tradition, Kathleen and Dominick’s Thanksgiving Dinner, but she did make their annual Christmas party. Paul and I sprung her from Amsterdam for the night. She refused to go into Kathleen and Dominick’s apartment sitting in her wheelchair. We helped her up, and she walked in on her own two legs (with a few helping hands) and ate her beloved croquembouche. After a couple of hours, Paul and I got her back to the nursing home.

Once again, my mom defied all the medical predictions. The head of the rehab center and her doctor told me that she was now able to return home. My mom was overjoyed. I was a bit nervous. There were still so many things she couldn’t do on her own. I didn’t quite understand how all this would play out.

I interviewed several potential live-in aides. Again, the social worker at the nursing home was incredible, talking me through the process, explaining exactly what I needed to look for and how to go about it. She gave me a list of places to contact. I called a few and didn’t feel the vibe. When I said to the director of one of the places that I would want to interview the candidates and so would my mom, she said, “We don’t allow interviews. If you and your mother don’t like them, we’ll replace them as soon as we can.” I said no they wouldn’t because there was no chance in hell I was going to be using their services. After several more calls, I went with a company called SelectCare. When I said we wanted to interview the women who might be working and living with my mom, the head of the agency said, “Of course. We wouldn’t let you hire anyone unless she got along with your mom.” She then asked me to tell her a bit about my mother. When I was done, she said, “I think I have two perfect people. They both can cook. It sounds as if that’s essential.”

In early January 2009, my mother returned to her apartment.

And thus began the next stage of her life, probably the most impressive one yet.

* * *

SHE WAS STILL quite aphasic, she needed thrice-weekly sessions of physical and occupational therapy, she had to use a cane to get around (no walker or wheelchair for her), and she moved at a snail’s pace. But as soon as she was home, my mother resumed her normal life.

She saw friends. Went to movies and to the theater. She went to restaurants all over the city. One day I called her up to say that friends had been to a brand-new restaurant and they thought we should try it.

“Already been there,” my mother said.

“Mom, the place has only been open a week. You’re almost ninety, you’re stroke-ridden, and it takes you fifteen minutes to get to the elevator! How the hell do you still go to restaurants before I even hear about them?”

She just cackled.

It helped enormously that three of the kindest, most compassionate, most wonderful people I’ve ever met had come into my mother’s life. They were her three aides from SelectCare: Jennifer, Janet, and Karlene. My mom kept her emotional distance from them at first, determined that she would eventually return to being self-sufficient and not need any live-in help. The doctors told me that would never happen, but doctors had used the word “never” many times before when it came to my mom. But this time they were right. The women rotated their shifts: Janet four or five days a week, Jenny on the weekends, Karlene whenever she was needed or as a vacation replacement. And over time my mom accepted them into her family and came to truly love them. In many ways they became more than family, they became friends.

Three other women also began to play an important part in my mom’s recovery. This second stroke eliminated my mom’s ability to cook—it took a long time for her right side to become even decently functional. She had to learn to write with her left hand and eat mostly with her left hand, two things I’d never be able to do. But cooking was too difficult. Her taste, however, remained. So one day, Janis suggested that an excellent birthday gift for my mom would be to hire a chef to come in and cook for her once a week and perhaps make meals that would last several days. My mom was thrilled by this idea and the first woman I hired was Jenny Cheng. Jenny’s parents ran a Chinese restaurant and she had gone to cooking school to learn how to make other types of cuisines. When I hired her, she was working as a line cook at a Tribeca restaurant. She, too, was an instant hit. Jenny didn’t just cook for my mom, they talked about food, which was terrific for my mother’s mental acuity as well as great speech therapy. When Jenny outgrew the job, Joyce Huang replaced Jenny, and Joyce was eventually replaced by Cynthia Tomasini. They all learned a lot from my mom, and not just about food and cooking. They learned about spirit.

Sometimes I would bring Jenny and the other cooks ingredients that I knew my mom especially liked. Or I’d bring packaged food that my mom loved to eat. I’d bring her Époisses, which made her face light up like a neon sign. I suggested that Jenny cook out of the Ratner’s book, so she made pirogen and blintzes for my mom (my mom gave both versions a C+—she was a tough customer). My mother told her chefs all about working at Spago on their special Passover dinners (my mom made the matzo balls) and helping Wolf prepare his Academy Award dinners. So I suggested they make dishes from Wolf’s books that my mom used to help prepare. My mom was delighted to rediscover these tastes.

One other thing helped engage my mother, physically and mentally. I’ve never had children, but I do have two cats in the post-Norton era. When Norton moved on to the great Kibble Bowl in the Sky, it took me three years to work my way up to being owned by another cat. At that point, I went to a breeder intending to buy another cat just like Norton—a male Scottish Fold whose ears had folded (not all of their ears do). But the first little creature who crawled her way into my heart was a girl whose ears sat straight up. It was love at first sight with this five-week-old dark gray kitten, who soon became Harper. But I really wanted a boy with real Fold ears, so when her orange and white brother—I named him Hud—flopped his way over to me, I found myself saying, “Okay, I’ll take them both.” I had taken Norton everywhere with me, so there was rarely a need for anyone to look after him. But it’s harder to travel with two of these guys, so now that my mom was in New York, she was recruited to be my cat sitter when I had to travel for any length of time.

The beautiful, regal Harper at age fourteen

She and Harper quickly bonded. My sweet girl cat would sleep next to my mom, my mom’s fingers grazing the top of the furry little body all night long.

Hud died suddenly when he was six, which devastated me way more than I suppose it should have. He was my particular pal and I’m pretty sure he thought I was actually his dad. When he died, Harper mourned deeply. She didn’t eat for weeks and she lost several pounds. She paced and cried and changed her personality from sweet and calm to nervous and cranky and unsure of the world. But she still loved going to my mom’s if I had to take a trip. The cat took comfort from my mother and my mom took comfort from my lovely, loving cat.

When she was taking care of Harper, I’d call my mom every day I was away. We’d chat, I’d see how she was doing, how she felt, and then my mom would say, “Okay, you’ve done your job. You can ask.” Sometimes I’d protest and say I was really calling to talk to her but she’d have none of it. “I know the truth,” she always said. So then I’d ask, “Okay, how’s Harper?” I’d get a detailed report and tell my mom that I’d talk to her the next day. “Just to talk to you,” I’d say. And she’d go, “Uh huh.” For years she’d ask if she could take care of Harper for a while—just to be sure I’d call her.

Mitch as a kitten

… and as an adult

Five years ago, I got Mitchum. Harper, now fifteen, is as delightful and special as a cat can be. But Mitch is Norton-esque. He is crazy smart and extremely beguiling and he goes out of his way to seduce everyone he meets. He has yet to meet a human whose lap he can’t be nestled into within fifteen minutes of the introduction.

My mom’s companions love Harper and Mitch as much as she does. Janet, especially, is always saying to me, “When are you going away again so I can see my little boy?” My mom pretends to be somewhat indifferent, but she lights up when they show up. Harper ignores the aides and goes right to my mother’s side. Mitch goes out of his way to say hello to and get petted by the aides, then hops on my mother’s bed and makes himself comfortable, as if it’s his bed and perhaps he’ll let her join him for the night.

* * *

MY MOM HAS two friends, Bill Chastain and Jean-Paul Desourdie, who are longtime partners. Bill is retired now from the movie business and JP is a caterer. I threw a surprise eightieth birthday for my mom at their apartment as well as a surprise eighty-fifth. Both times, but especially for the second bash, as the door opened and everyone yelled “Surprise!” it did occur to me that it might not be a great idea to give such a sudden shock to a woman of that age with a dicey medical history. But my mom took it all in stride and both parties were smash hits.

When my mom turned ninety we had one of the greatest parties ever. It wasn’t done as a surprise and pretty much everyone she knew, on both coasts, was invited. Just about everyone came, too. We had sixty or seventy people at Bill and JP’s apartment, the food was great, and, in essence, my mom got to witness her own laudatory memorial service because so many of her friends—young and old—got up and spoke. People talked about how much she meant to them, how strong she’d been for them at different points in their lives, and how strong she helped them become. They talked about the food she’d made and the lovely things she’d done to help them. It was a rare and moving outpouring of love.

One of my mother’s oldest friends, Takayo Fischer, composed a song for her and sang it. Paul, who has known my mom almost as long as I have, and I prepared a PowerPoint presentation purportedly showing the complete arc of my mom’s life. A lot of it was true and a lot of it was completely made up. Paul did the technical stuff and did it brilliantly, so dozens and dozens of photos popped up on the big white wall of the apartment as I narrated my mom’s story. We had uncovered photos of my dad in a Camp Mohican show and a picture of my mom’s camp bunkmates. My cousin Jon Korkes delivered to us a home movie of my mom and dad when they were in their early twenties, kissing and fooling around for the camera. I had a picture of my mom walking through the jungle in New Guinea with a studly native, explaining that this was my mom’s wild period, when she ran away from my father to have her torrid affair. We had family photos from different eras and lots of photos of my mom at different ages. People laughed throughout—my mom most of all—but tears were flowing freely by the end.

I thought all of the speeches were completed, but my nephew Morgan suddenly raised his wineglass and made a toast.

“I want to say something about my grandma,” he said. “I think she’s the greatest person I’ve ever met.” He then went on to talk about how much she meant to him and why. It was eloquent and moving and my mom, who rarely gets openly emotional, was definitely choked up to the point of repeatedly wiping her eyes.

After that toast, I told Morgan that he was now officially a mensch.

My mom stayed at the party until the very end. She ate, drank, and soaked up the love. When it was time to leave, I asked her if she’d had a good time.

“Oh yes,” she said. “Oh yes.” That was all she really had to say.

“You want my take on the whole party?” I asked. She nodded. “You have a lot of children,” I said. “All the people here, they either think you’re their mom or they wish you were their mom.”

“And what’s the lesson to learn from that?” she asked.

“You’re lucky,” I said.

And my mother said, with a triumphant smile, “No, you are.”

THE TORNABENES’ BUCCATINI WITH CAULIFLOWER, PINE NUTS, CURRANTS, ANCHOVIES, AND SAFFRON

Gangivecchio means “Old Gangi,” which means that the town of Gangi that exists today is the new Gangi. The spot where the thirteenth-century abbey stands—now the inn and restaurant run by Giovanna Tornabene and her brother, Paolo—was the site of the original village. For six hundred or so years, monks ran the magnificent abbey. There are remnants of that period everywhere you look: the seventeenth-century chapel off the courtyard, sixteenth-century frescoes on the walls of Giovanna’s apartment inside the magnificent walled structure. Several years ago, I participated in an archaeological dig on the grounds of the abbey and uncovered two-thirds of an ewer that the archaeologist from Palermo told me was from 300 BCE. Having discovered something that old and beautiful—and holding it gingerly in my palm—brought tears to my eyes. Wandering through the ruins of the abbey, I once stumbled upon a stack of beautiful terra-cotta tiles. When I showed them to Giovanna, she said, “Oh yes, those are seven hundred years old.” She then offhandedly suggested that I should use the tiles to build the barbecue I wanted to erect outside the cottage, and that’s where they now sit. Every time I spill grease from a sausage onto the ancient tiles, my stomach hurts a little bit.

Wanda Tornabene, the mother of Giovanna and Paolo, was an amazing woman. When I met her, in 1991, she was in her late sixties and she was no one to mess with. Like a lot of Sicilians, particularly after World War II, the Tornabenes were gentry who ran out of money. Even now, these Sicilian gentry have managed to have loyal servants and a certain regal carriage and an air that clearly conveys the belief that they are meant to lord over someone, somewhere. But at some point, they have all had to either go to work or face destitution. For many, being broke beats the humiliation of actually having to do real labor. Wanda was not one of those. When her husband was still alive, she put her foot down. She said that they were not going to sell off any more of the land they owned (once a thousand acres or so). Nor were they going to sell off any more antique furniture from the abbey. Instead, she said, they were going to open a restaurant. Enzo, her husband, was mortified. Cooking for, serving, and waiting on local people, whom they knew? People who should be working for Enzo and his family? No, this was not going to happen.

It happened. Because Wanda made it happen. Gangivecchio, over time, became the best restaurant in Sicily, and Wanda ran it the way a great general commands his (or her) troops. She gave orders, the people who worked for her as well as her family followed those orders, and somehow they all developed an appreciation for her passion and her talent. That appreciation developed into loyalty. And even love.

When Wanda’s husband died, in the early 1980s, the restaurant is what kept her and her two children going. On the abbey’s grounds were acres of superb vineyards and four hundred olive trees and cows and horses and chickens and cherry trees and almond trees, and although they could keep the land and its treasures alive, they could not mine them the way they should be mined. That was for a different era. What Wanda could control, what she could mine, was food. She was a magnificent cook and loved food fiercely. For my mother, food was a way to strengthen her identity. For Wanda, food was part of her. It was her blood.

The Tornabenes—Wanda, Giovanna, Paolo—sacrificed a lot to keep Gangivecchio in the family. Giovanna now says that Gangivecchio is her child: her purpose on earth is to keep it alive.

When she was in her mid-eighties, Wanda got sick. Eventually she went blind. But she would not leave Gangivecchio. She said she would die before she left Gangivecchio.

In 2012, when she was eighty-seven years old, Wanda stopped eating. Food is what gave her not just a way to live but also a reason to live. Food, literally and spiritually, had kept her alive. When she decided she did not want to keep going, she knew how to stop. She just pushed the food away. She removed her reason for living and she died.

* * *

MY MOTHER PICKED the Tornabenes’ buccatini as her favorite pasta. It’s mine as well.

When I was editing Wanda and Giovanna’s first book, written with an American writer, Michelle Evans, who learned to speak fluent Italian just so she could do the book, the Tornabene women told me their secret to making great food: there should be no more than five main ingredients in any dish. This one just manages to squeeze itself in. Pasta is not an ingredient, in case you’re wondering. As Giovanna would say, pasta is a member of the family.

I have made this pasta, over the years, perhaps more than any other. Recently, I cooked it standing alongside Giovanna in the kitchen at Gangivecchio’s inn. The dish came out better when Giovanna was involved. I don’t understand why that is, since I do it the exact same way at home. Perhaps her ingredients were better. Or perhaps she is actually something I’m not: a natural cook.

The same way I love wine but don’t have the perfect palate, I don’t have the magic cooking touch, either. I’m a good cook. I swear. I just don’t have the magic. Giovanna has the same magic that Wanda had. She’s a great cook and her Bucatini alla Palina, which is the real name of this dish as written in her first cookbook, tastes better than mine. But magic or no magic, you’re going to like it.

I don’t know why this dish works best with bucatini, but it definitely does. The pasta’s thickness takes the sauce better than spaghetti and the length allows a bit more pasta on one’s fork than, say, penne. But don’t overanalyze. As Tom Stoppard once said about good writing: It works because it works.

INGREDIENTS:

Salt

1 small cauliflower, with florets cut into small pieces, approximately the same size

¾ cup olive oil

½ cup finely chopped shallots or onion

2 tablespoons minced anchovy fillets

¼ teaspoon powdered saffron

½ cup currants, soaked in hot water for 10 minutes and drained

¼ cup pine nuts

Freshly ground black pepper

1 pound bucatini, broken in half if need be

¾ cup toasted bread crumbs (see below)

DIRECTIONS:

Serves 6 as a first course or 4 as a main course

Bring 1½ quarts of water to a rolling boil in a large pot. Stir in 1 teaspoon salt and add the cauliflower. Cook at a slow boil for about 5 minutes. Using a slotted spoon, transfer the cauliflower to a bowl. Reserve 1 quart of the cooking water.

In a large saucepan, heat the olive oil and cook the shallots or onion and anchovies over medium heat for 5 minutes. Add ½ cup of the cauliflower water, saffron, currants, and pine nuts. Combine well and season to taste with salt and pepper. Simmer for 15 minutes. Add a bit more cauliflower water if you sense it’s needed.

Meanwhile, combine 3 quarts of water and the reserved cauliflower cooking water and bring to a rolling boil in a large pot. Stir in 1½ tablespoons of salt and add the bucatini. Cook until al dente, or just tender, stirring often.

Reserve 1 cup of the pasta water, drain the pasta, and return it to the pot. Immediately add the sauce and gently toss. Add more pasta water, as needed, if a thinner sauce is preferred. Cover and let the pasta rest, off the heat, for 5 minutes. Toss again and serve with the toasted bread crumbs.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: NOT TO KEEP LORDING IT OVER YOU, BUT WHEN I WAS MAKING THIS RECENTLY WITH GIOVANNA, SHE ADDED ONE FINAL INSTRUCTION AND I HIGHLY RECOMMEND IT. AFTER THE PASTA’S READY, PUT IT IN A BAKING DISH, WITH SOME OF THE BREAD CRUMBS—WHICH, IN HER LITTLE BOWL, SHE COMBINED WITH PARMESAN CHEESE, SO THEY WERE INSEPARABLE—AND PUT IT IN THE OVEN AT 400 DEGREES F FOR 10 MINUTES. MMMM-MMMM!)

BREAD CRUMBS FROM LA CUCINA SICILIANA DI GANGIVECCHIO

Grate thoroughly dry two- or three-day-old firm Italian country bread—with or without the crust. (We always include the crust for the slight variety of colors it produces and, perhaps, a hint of extra flavor.)

One cup of bread crumbs is a sufficient amount for four servings of pasta. Heat 1½ tablespoons of olive oil in a frying pan and swirl it all over the bottom of the pan. Stir in the bread crumbs with a wooden spoon. Turn them repeatedly over medium-high heat, spreading them across the pan, until they blush a rosy golden-brown color. This takes only 2 to 3 minutes. (Double the amount of olive oil for 2 cups of bread crumbs.) Spread the toasted bread crumbs onto a plate, allowing them to cool, stirring once or twice before using them.

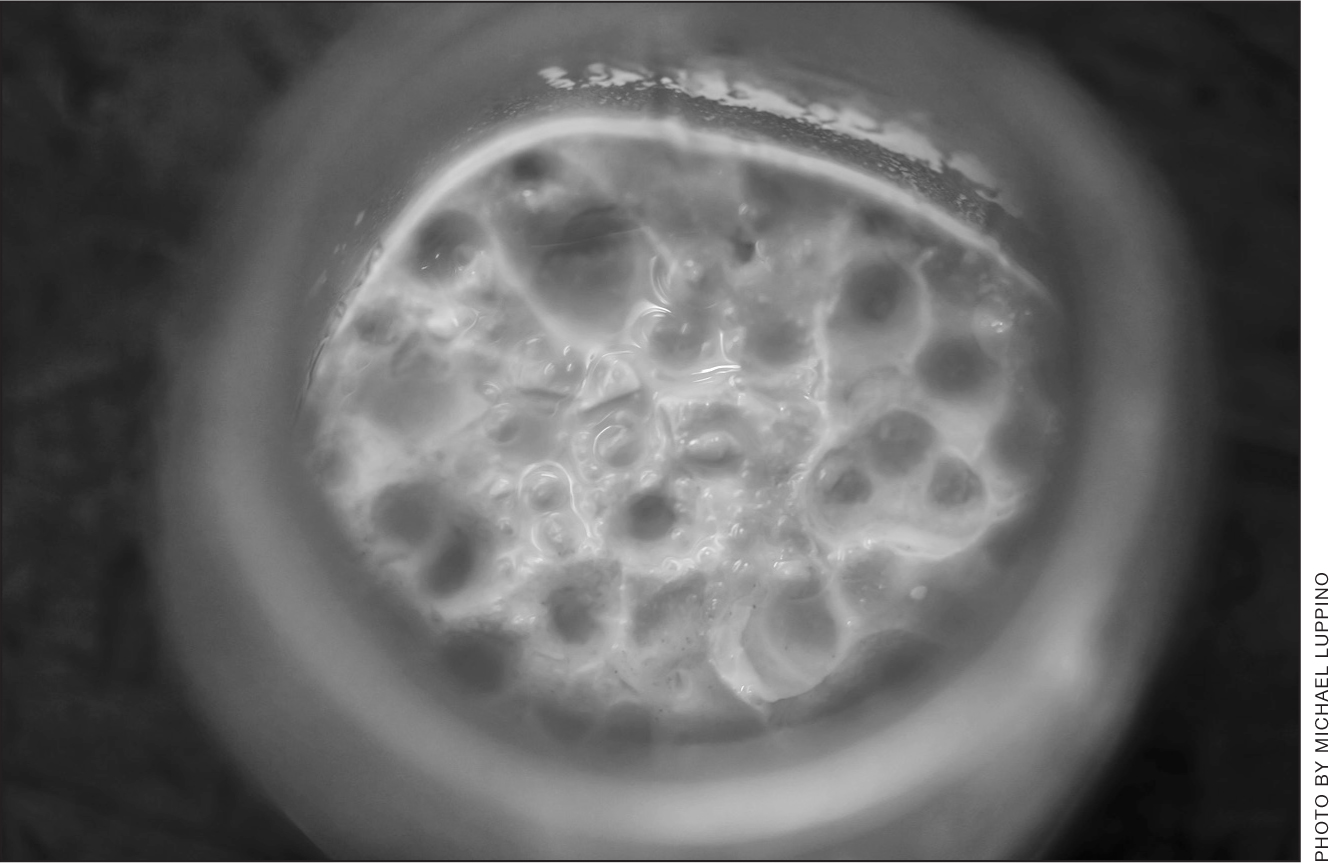

The final stage of the cauliflower, etc., pasta—about to go into the oven

Serve toasted bread crumbs in a little bowl sitting on a saucer with a small spoon, or in a grated cheese dish with a spoon. Place the bowl on the table and pass it around so the bread crumbs can be sprinkled on top of the pasta as you would Parmesan cheese.

We have found that toasted bread crumbs keep well for only a day, so they must be made the same day they are used.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: OR YOU CAN USE STORE-BOUGHT BREAD CRUMBS. NO, THEY’RE NOT AS GOOD, BUT THEY’RE FINE. AND IF YOU SERVE THEM IN A LITTLE BOWL WITH A SAUCER, PEOPLE WILL THINK THEY’RE BETTER THAN THEY ARE.)

TARTE TATIN

I am a total Francophile. I have spent a lot of time in France, working, playing, living, eating, and drinking. Yes, yes, I know all the flaws with the French—they think they’re better than everyone else, they think their culture is so superior, they lord their food and wine over the rest of the world. Well … um … I tend to agree with them. In quite a few ways, they are somewhat better than anyone else: they’re stylish, educated, informed, involved, sophisticated, they drink the best wine, and when it comes to food, it has always amazed me that almost any average, ordinary French person can throw a dinner party, organized at the last moment, and provide a meal that is 100 percent satisfying. I’ll admit the whole capitulation-to-the-Nazis thing gives me pause. And so does the fact that most of their culture—their architecture, literary output, and music—over the past forty years is giggle-inducing. But, in one of the greatest philosophical observations ever made, written by Billy Wilder and spoken by Joe E. Brown at the end of Some Like It Hot: “Nobody’s perfect.”

There is no question that my romantic view of the French has been stoked by the books and films I’ve loved all my life: Fitzgerald writing about Paris in the twenties, the movies of Lelouch and Truffaut. So yes, I tend to view French people and French life through rosé-colored glasses.

I was once at the apartment of friends, Nikolas and Linda Kaufman, who lived in Paris. She is American and he is very, very French. Linda is an amazing home cook, one of the best I’ve ever known, and she made a superb meal that night. But as is often the case, the oohs and aahs came over the dessert, which was Nikolas’s domain. It was a tarte tatin and I was staggered by it. I told him I would love to know how to make it. He responded that it was quite easy. He said that there was a great French chef who wrote a cookbook that contained the perfect tarte tatin recipe. He assured me that if I followed it exactly, anyone who ate the tarte would swear it was made by an honest-to-goodness French person. He then led me back to their kitchen, pulled a cookbook from a shelf, and handed it to me. The great French dessert chef was Martha Stewart.

Martha Stewart’s Tarte Tatin Recipe

INGREDIENTS:

5 to 6 medium apples, such as Braeburn

¾ cup granulated sugar

3 tablespoons water

4 tablespoons (½ stick) unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

1 lemon

½ recipe pâte brisée (recipe follows)

DIRECTIONS:

1. Peel, halve, and core apples. Set aside half of the apples. Quarter the remaining apples and transfer them to a large bowl. Squeeze a lemon over the apple slices and set aside.

2. Combine the sugar and water in a 9-inch cast-iron skillet. Bring the mixture to a boil over medium-high heat; immediately reduce the heat to medium and cook until the mixture begins to thicken and turn amber. Remove from the heat and stir in the butter.

3. Place the reserved apples in the center of the skillet. Decoratively arrange the remaining apple slices, cut side up, in the skillet around the reserved apples. Continue layering the slices until level with the top of the skillet. Cut any remaining apples into thick slices to fill in the gaps. If the fruit does not completely fill the pan, the tart will collapse when inverted.

4. Place the skillet over low heat and cook until the syrup thickens and is reduced by half, about 20 minutes. Do not let the syrup burn. Remove from the heat and let cool.

5. Preheat the oven to 375 degrees F. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper and set aside.

6. Roll out the pâte brisée to a 10- to 11-inch circle, about ⅛ inch thick; transfer to a baking sheet and chill until firm, about 30 minutes.

7. Place the pâte brisée over the apples and tuck the edges. Transfer the skillet to the prepared baking sheet; transfer the baking sheet to the oven, and bake until golden brown, about 35 minutes. Transfer to a wire rack and let cool for 15 to 20 minutes. Loosen the pastry from the skillet using a sharp knife. Place a rimmed platter over the skillet and quickly and carefully invert. Serve immediately.

RECIPE FOR PÂTE BRISÉE (AUTHOR NOTE: FANCY WORD FOR PIE DOUGH)

Pâte brisée is the French version of classic pie or tart pastry. Pressing the dough into a disk rather than shaping it into a ball allows it to chill faster. This will also make the dough easier to roll out, and if you freeze it, it will thaw more quickly. (AUTHOR NOTE: I DON’T GET THIS WHOLE DISK VS. BALL THING. SMOOSHING IT INTO A BALL SEEMS TO WORK FINE.)

Makes 1 double-crust or 2 single-crust 9- to 10-inch pies

INGREDIENTS:

2½ cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon sugar

1 cup (2 sticks) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into small pieces

¼ to ½ cup ice water

DIRECTIONS:

1. In the bowl of a food processor, combine the flour, salt, and sugar. Add the butter and process until the mixture resembles coarse meal, up to 10 seconds.

2. With the machine running, add the ice water in a slow, steady stream through the feed tube. Pulse until the dough holds together without being wet or sticky; be careful not to process more than 30 seconds. To test, squeeze a small amount together: if it is crumbly, add more ice water, 1 tablespoon at a time.

3. Divide the dough into two equal balls. Flatten each ball into a disk and wrap in plastic. Transfer to the refrigerator and chill at least 1 hour. The dough may be stored, frozen, up to 1 month.

The last time I was at Gangivecchio I told Giovanna that I wanted to make a tarte tatin and she immediately said that we should prepare one together. I showed her the Martha Stewart recipe and she agreed to follow it. More or less. During the course of our baking, Giovanna showed me a few tricks to make Martha’s recipe a bit simpler and even a bit better.

The following Sunday, she was having a luncheon for eleven people, so we went into the kitchen around ten o’clock and began to make the filling. Cooking with Giovanna is not a fully satisfying participatory experience. If you can keep up, great. If not, you better get the hell out of the way. Especially if ten guests are on their way to the albergo—hotel—for a meal. On many of these steps, I just got the hell out of the way.

We used her cast-iron skillet. It’s not necessary, but it really does work best. If you don’t have one, any frying pan will suffice. But you’ll feel a lot more professional if you go for the cast-iron one.

We put the butter in, as Martha says to do, and melted it over low heat.

Next: time to core and peel the apples. Giovanna needed a large tarte, since so many guests were coming, so she decided we’d need fourteen apples. And this is where it started to get ugly. Giovanna has a lovely woman, Giuseppina, who helps her out from time to time, cleaning and cooking and waiting on tables. Giuseppina pushed half of the apples in my direction, she gave me a knife so I could start peeling, and she picked up her own knife at the same time. I did my best to visualize my knife skills class, got my confidence up, and began. I inserted the blade carefully under the skin, began slicing away, got maybe an inch of peel off. Satisfied that it looked good, I did the same thing again, and then again, carefully and precisely. When I finished with my first apple—cleanly peeled, looking very professional—I turned proudly to Giuseppina, who was staring at me with a confused expression. In addition to staring, she was also holding twelve perfectly peeled apples. Pride instantly evaporated and transformed into dismay. To make me feel worse, Giuseppina took the final apple and peeled it while I watched—she stuck the knife in and in less than five seconds the peel was off, with one continuous slice as if she were quickly unwrapping a small gift engulfed in tissue paper. Shaking her head, she handed me a different knife so I could start coring. But before I could move, Giovanna raced over, grabbed the knife out of my hand, and replaced it with an apple corer. She didn’t have to say anything. I knew she didn’t want to have to take me to the Gangi emergency room. Giuseppina stuck with her knife. I did manage to core more than one apple; I did four; she did the remaining ten. The process seemed easy enough when I started: an apple corer is inserted into the apple, directly over the core, and pushed straight down, then removed with the core in its grip. I’m not sure how I managed this, but the tip of my corer kept coming out the side of the apple instead of at the bottom. Each time, I had to insert the thing twice. All of the apples I cored looked as if some giant worm had managed to slither inside from a perfectly round third hole somewhere to the right or left of the core. My one tip on this step is: although Giuseppina could peel and core her apples in the time it took the butter to melt in the pan, I suggest coring the apples before you turn the heat on under the butter.

Doing my best to ignore Giuseppina’s look of bemusement, I moved over to the stove. The butter was just about melted. Giovanna said that she always added the sugar by eye. Her exact words were, “I have not a weight.” So she mixed the sugar in and just did her best to make the correct distribution. The next instruction from her: “Don’t touch.” All you have to do at this point is let the sugar and butter caramelize over medium-low heat.

Next: Giovanna allowed me to squeeze a lemon over all the apples. This prevents them from turning brown and makes sure they’re as beautiful as possible for the finished product. As Giovanna said about this process: “When you peel the apples, it’s like the sun on your skin.” The lemon works as sunblock on naked apples.

Remove from the heat when the mixture is caramelized. This is also done by sight: when the thing is bubbling and brown and looks kind of gooey, but before it’s burnt, it’s done.

Put the apples in the pan—and here is Giovanna’s clever trick that differs just a bit from Martha’s recipe: she cuts off the bottom of each apple so it’s flat and she stands them all up in the pan rather than laying them down. First they go around the edge of the pan, forming a perfect circle, then you form another circle within that one, then another, until the pan is completely filled with upright apples. It’s like a bunch of little apple soldiers standing at attention.

Turn the heat back on to medium. When the bottoms are brown, turn them over and brown the other side. Do it carefully, one apple at a time. When both sides are done—tops and bottoms should be nice and brown, but be careful not to burn them—remove the pan from the heat. The apples have to cool before you put the crust on or the crust will melt and sag into the mixture. That’s a big no-no.

I get nervous making crust. Giovanna kept saying it was easy and for her it was. The crust has to be done in advance because it needs time in the refrigerator. You can do it two or three hours ahead of the filling, but it’s probably better to do it the day before so you don’t screw it up.

It’s confession time: I didn’t make the crust with Giovanna. She did it the day before and stuck it in the fridge. She wasn’t worried about screwing it up, she was just too busy to do it the day of the luncheon. When I got home to New York, I did the Martha version just to make sure it’s doable by people like me. It is. She’s Martha Stewart—what did you expect?

When the apples are cool, cover them and the skillet with the dough, rolled out as Martha instructs. Then, in the oven it goes. Keep it in until the dough looks like a nice, brown crust.

Giovanna’s Tarte Tatin. See what happens when you stand those apples up?

Take it out of the oven and let it cool. Eventually, you’re going to turn the thing over so the crust is on the bottom. There are two ways this will fail: If the tarte isn’t cool. Or if you don’t have enough apples in the pan (think of them as columns holding up the crust when you do the inversion). You turn it over by putting a round platter tightly on top of the dough, take a deep breath, utter a quick prayer if you’re a spiritually minded person, and flip. You should have a perfect tarte tatin: browned apples standing on a lovely crust.

Serve—whipped cream can be a nice addition—and take your bows.

NANCY SILVERTON’S CHALLAH AND BOULE

I have been lucky enough to work with several actual geniuses over the course of my career. Not just really smart people but geniuses. People who have a vision unlike others in their field; people who produce things on a different level from others in their field. I’ve edited books and written screenplays with Roman Polanski. Genius. I’ve edited books by Stephen Sondheim and worked with him on a show that I cocreated. Genius genius genius. I’d add Robert Hughes, whom I’ve also edited, to this short list. And if I can add the word “eccentric” before the word “genius,” I would have to include Bill James of Baseball Abstract fame. And Nancy Silverton definitely belongs. She is a genius baker.

Because of my mother’s friendship with Nancy, I’ve known her for ages and have watched her rise in the food world with considerable awe. She was the original pastry chef at Spago. The Los Angeles restaurant she ran with her then-husband Mark Peel, Campanile, was innovative and superb (never more so than when Nancy instituted Grilled Cheese Sandwich Night every Thursday). She now oversees three magnificent L.A. restaurants, all in the same building: Osteria Mozza, Pizzeria Mozza, and Chi Spacca. But of all her successes, the one I found to be the most intoxicating was the La Brea Bakery, which she started in 1989. Nancy’s bread baking is beyond compare. I still dream about the chocolate cherry bread she used to sell when the bakery was at the front of Campanile.

You can delve into the pleasures of Nancy writing about wheat and bread texture and all sorts of other doughy topics on your own if you read Nancy Silverton’s Breads from the La Brea Bakery, which I believe is the best book ever written about bread and bread baking. But I’m only going to discuss her starter, as well as her boule and her challah, my mother’s two favorite breads.

So about Nancy’s starter: I find it absolutely impossible to make. Every time I’ve tried I’ve totally screwed it up. I consider this a major failing on my part.

Fortunately, good old Abby Levine, he of the successful salmon coulibiac preparation, really knows what he’s doing when it comes to baking bread. He makes it all the time, although he tends to use the ingenious and almost fail-proof no-kneading method, perfected and made famous by Jim Lahey, founder of the Sullivan Street Bakery. For my mom, however, I told Abby that I needed serious support on the bread front and that I wanted to go old school and use Nancy’s starter and recipes. Foolishly, he agreed.

You can make Lahey’s great bread in one day. Start from scratch in the late afternoon and have it warm for dinner. Nancy’s sourdough starter takes fourteen days! Two weeks! And that’s before you even start baking. The upside to that is once your starter is grown, as long as you feed and maintain it, it will last the rest of your life. It’s kind of like Audrey II in Little Shop of Horrors except not as funny and you eat it instead of vice versa.

DAY 1: GROWING THE CULTURE (FERMENTATION BEGINS)

(NOTE FROM ME, NOT NANCY: SO DO THE DRY SWEATS)

HAVE READY:

Cheesecloth

Scale

One 1-gallon plastic, ceramic, or glass container

Rubber spatula, optional

Plastic wrap, optional

Long-stemmed, instant-read cooking thermometer

Room thermometer

1 pound red or black grapes (pesticide free)

2 pounds (about 4 cups) lukewarm water, 78 degrees F

1 pound 3 ounces (about 3¾ cups) unbleached white bread flour

I am not going to go through every step of Nancy’s recipe. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to her to give away all her secrets. But I will tell you that, out of respect for Nancy, Abby and I followed the instructions perfectly. I was so excited during this process that I went out and purchased the same digital scale Abby uses and the same measuring cup, which has both American and European measurements on the side. I also bought the same digital thermometer, because I couldn’t believe how cool it was to actually know that the water we were using was exactly seventy-eight degrees.

Working side by side in Abby’s kitchen, we each made the starter. We did precisely the same thing at the same time. Then we sealed our starter into our gallon bowls at the exact same moment. I took my starter home. Abby kept his in his kitchen.

Nancy’s book provides day-by-day instructions for the remaining thirteen days of growth. By the time I got home from Abby’s, he had sent me an e-mail with those instructions, formatted to go into my e-calendar. So for the next many days, the first thing I did every day was check that calendar. Along with 8:00 a.m. gym and 12:30 p.m. Lunch with President Obama (okay, I made that one up, but I really do go to the gym) were such things as: Day Two: You will notice a few tiny bubbles in the mixture, and the bag of grapes may have begun to inflate. And: Day Ten: Begin early today, because this is the day the culture becomes a starter—and the day you put it on a permanent feeding schedule.

Abby and I swapped photos on our phones every day, sometimes several times a day. We compared the odors emanating from our respective one-gallon containers to the best of our descriptive abilities. We discussed the nature of bubbles in late-night texts. It was a little like starting a new romance, except, even on its best days, the object of my desire had a “distinct, unpleasant, alcohol-like smell” and “a yellowish liquid top layer.” On Day Three, Abby was certain his had flopped. There were no bubbles and very little grape inflation. I, on the other hand, was brimming with confidence. My grapes were enormous—I boasted about them in several texts to Mr. Levine—and bubbles were aplenty. By Day Seven, my confidence had flagged substantially and Abby’s was on the rise. By Day Eleven, I was certain I had bombed out big time. Abby was questioning his starter but hadn’t lost all confidence.

On Day Fourteen, my starter was as dead as anything could possibly be. It was, as was I, a dismal failure. But Abby texted me a one-word verdict on his experiment: SUCCESS!

His starter lived to be baked another day.

On Day Fifteen, Abby sent me a photo of the boule he made from his starter. It was perfectly round and crusty and I could practically smell the enticing yeasty aroma through my phone.

Determined to succeed, I went back to the drawing board. I decided that it was the cab ride home from Abby’s, with my starter in tow, that had done me in. So I began again, in my own kitchen. I got my pesticide-free grapes, used my scale with the precision of a Nobel Prize–winning scientist, and pointed my digital thermometer at seventy-eight-degree water. This starter was my Terra Nova Expedition to the South Pole and I was Roald Amundsen. That analogy turned out to be a bit flawed. I turned out to be Captain Robert Scott rather than Amundsen. The South Pole won. On Day Eight, after watching it refuse to bubble, expand, smell wonderfully yeasty, or develop into anything remotely like what Nancy described in her book or what Abby had inserted into my daily calendar, I threw my starter in the garbage.

My pathetic and pretty gross starter

But I love my digital thermometer

CHALLAH

Having proved a dismal failure with the starter, I was dependent on Abby to come through for my mom. I told her what we were doing—and was honest about our respective roles and successes and failures. Abby’s boule was mom-worthy. But challah was a different challenge.

Even Nancy, who thinks that all baking is easy, says that challah is one of the hardest shapes to make. I accepted the fact that I was out of my league. Unwilling to face failure again, I went with Plan B: begging Abby to do it for me.

Remembering how deftly and artistically he’d added the fish shape to our coulibiac, I knew he could manage the challah’s braid. I was correct: he made something that looked like the challah I used to get at Ratner’s take-out counter. But the taste?

Solid.

Not incredible, but good.

He was more critical than I. But he could afford to be; he’d succeeded in making the damn thing and he could calculate what he needed to do next time to improve the texture, the design, and the taste.

Me?

I could only dream.