From 1900 through the 1910s, most films reproduced only theatrical space on screen. Nonetheless, there were efforts to increase the vocabulary of filmmaking.

In the late 1900s, intertitles already were incorporated to explain the contents of each scene, and in A New Version of the Cuckoo (Shin hototogisu, 1909), a film version of a literary and shinpa classic, flashbacks, although crude, were used when the heroine recounts her life story after she is rescued from leaping to her death. As far as we can determine based on current research, the earliest efforts to divide scenes into multiple shots took place in 1909 at Yokota Shōkai. Techniques such as close-ups, tracking shots, and crosscutting were introduced by director Inoue Masao around 1917, with The Captain’s Daughter (Taii no musume). But despite these innovations, the idea that the only reason to divide a scene was to compensate for inexperienced actors remained deeply rooted, and making a scene out of several different shots, which we usually think of as a basic and fundamental technique of classical Hollywood filmmaking, had yet to become universal. The consciousness of enlivening narrative action through montage had yet to take root.

The Pure Film Movement (jun eiga geki undō) began in 1918 and the changes it brought were much more profound than these minor technical innovations. The movement was literally a reorganization of the epistemological paradigm of cinema. For this movement, cinema was a text exposed before the gazes of an anonymous audience, a text that did not change with a particular performance or audience. Intellectuals had already abandoned the term katsudō shashin (moving pictures) and had come to select eiga (cinema), which had higher cultural connotations. Eiga had been used to indicate magic lanterns before the cinematograph was imported. Consequently, in 1896, to distinguish movies from this earlier definition, such terms as “automatic lantern,” “dancing photographs,” and “moving pictures” were used; however, eventually such distinctions came to be unnecessary. The shift from “moving pictures” and similar terms to “cinema” announced the fact that film had come to be recognized as a medium completely distinct from all other electric spectacles, panoramas, and so forth. Of course, for this word to filter into mass consciousness, it would have to wait until the furor over the Pure Film Movement subsided, around 1922.

Before taking up this movement itself, I will discuss briefly the birth of film journalism and criticism where the movement originated.

The first film journal, Motion Picture World (Katsudō shashinkai), was published by the Yoshizawa Shōten Company in 1909. The journal initially focused on novelizations of films produced by Yoshizawa Shōten itself, to make them easier to understand. Beginning the following year, however, there appeared guides by critics on methods of classifying films and ways to write about film. In the 1910s, a flood of coterie journals was born, springing largely from college students. In 1919, Kinema Junpō was launched as a coterie journal started by a small circle of friends. It would go on to be the representative film journal of Japan, with its top-ten lists, in particular, considered authoritative for many years. The majority of these coterie journals praised Western films while mercilessly castigating Japanese films for lacking the essence of cinema. It was out of these debates in coterie journals that the leader of the Pure Film Movement, Kaeriyama Norimasa (1893–1964), would emerge.

Kaeriyama wrote a theoretical treatise in 1917 called “The Production and Photography of Motion Picture Drama” (Katsudō shashin geki no sōsaku to satsueihō), in which he insisted that cinema must not imitate vulgar theater, but rather, find its own cinematic essence, purify it, and make it visible. He called for replacing scripts from stage plays with scripts written especially for film, using actresses instead of onnagata and getting rid of the benshi in favor of intertitles. He considered speed and realism—as well as illusion—indispensable to true cinema.

Based on his theories, he directed two films in 1918 at Tenkatsu Studios (Tennenshoku katsudō shashin): The Glow of Life (Sei no kagayaki) and Maiden of the Mountains (Miyama no otome). The former concerns a virginal girl at a coastal resort who is seduced by an aristocratic boy and then abandoned; after this, however, the girl gets happily married and refuses the aristocratic boy’s effort to seduce her once more. In the latter, the young woman of the mountains, beset by misfortune, meets up with an explorer and presses upon him the significance of the sacred mountain, defusing his passion for the acquisition of gold. The director, by inserting intertitles in both Japanese and French, obviously had international distribution in mind. Rather than using shinpa players, as would be conventional, Kaeriyama made use of shingeki players. Diametrically opposed to shinpa, shingeki was a genre of theater that arose from the influence of modern Western theater, focused largely on the works of Chekhov, Gorky, and Ibsen, and for a predominantly intellectual audience.1 Through the participation of shingeki actors, cinema began to be liberated from its shinpa roots, and one of the aims of this production was to elevate the standing of cinema by presenting it before a higher social class. In addition, Kaeriyama supposedly shot the first female nude scene in Japan in his film, The Phantom Woman (Gen’ei no onna). However, this film is lost, so unfortunately, this story cannot be confirmed.

Kaeriyama’s plans caused quite a stir in the film industry. Around the end of the First World War, Hollywood studios began to establish branches little by little in Tokyo, and screenings of American films started to proliferate. In particular, Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) came as an enormous shock to young Japanese cineastes. In the 1920s, German expressionist film out of Universum Film-Aktien Gesellschaft (UFA) appeared, followed by French avant-garde films. Within this environment, new studios emerged, including Kokkatsu (an abbreviation of Kokusai katsuei) in 1919; in 1920, Taikatsu (an abbreviation of Taisho katsuei) appeared, and Shōchiku, which previously had been involved only in the production of Kabuki plays, established a studio at Kamata, in Tokyo, and began producing films.

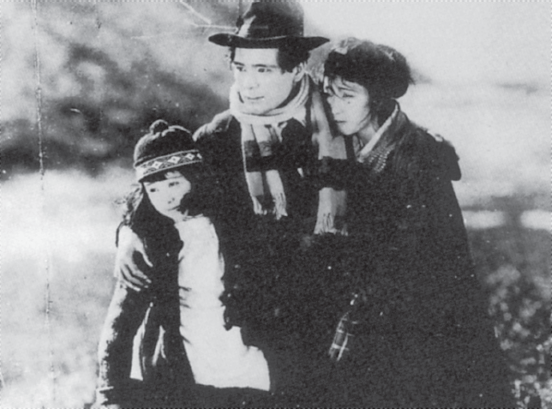

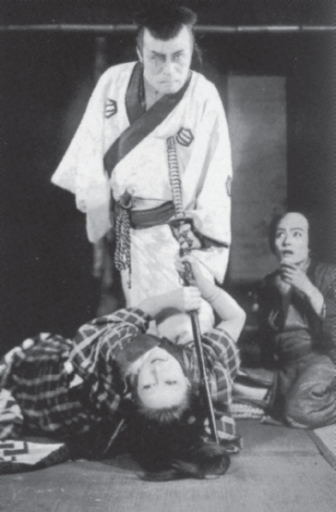

Souls on the Road (dir. Murata Minoru, 1921).

Shōchiku built an actor’s training school, entrusting it to Osanai Kaoru,2 a strong advocate of the shingeki movement. Actresses emerged from Shōchiku one after another. But in fact, women were on screen before this. In the 1900s, for example, women appeared in film adaptations of women’s theater, and in the 1910s, female shinpa roles were played by women in rensageki. But the actresses for Shōchiku were decidedly different from both. At Shōchiku, a star system was established modeled on Hollywood, and actresses were produced based on modern Western theatrical training. Souls on the Road (Rojō no reikon, 1921), directed by Murata Minoru under the guidance of Osanai Kaoru, is a morality play about Christian philanthropy that begins with a quote from Gorky in Russian. Set in Karuizawa, which was a resort town developed by Westerners at the time, the narrative revolves around a bourgeois daughter who invites two vagabonds into her home to celebrate Christmas. This primary narrative incorporates a subplot about conflict and reconciliation between a father and his artist son who live next door to each other. This theme resonated strongly with contemporary literature, particularly that of the Shirakaba school, a literary movement heavily influenced by Western ideas of idealism and humanism. Murata freely made use of all manner of cinematic techniques, including crosscutting. Overall the impression the work gives is highly confusing, but the main actress Hanabusa Yuriko became famous. The cheerful cuteness of Kurishima Sumiko, who was featured in the contemporary film Poppies (Gubijinsō, 1921), based on Natsume Sōseki’s novel, endeared her to audiences of the new generation, who were fed up with the stylized femininity of shinpa onnagata. Kurishima would go on to become the first female star of Japanese cinema.

Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, who had already secured a reputation as an up-and-coming modernist writer, was profoundly curious about film production. As a literary consultant for Taikatsu, he had Thomas Kurihara, recently returned from Hollywood, direct Amateur Club (1920), from his own script. The film was a slapstick comedy, featuring young boys and set in the South Seas, but one can detect its parodic intent when they do a mock-Kabuki scene, playing up the idea of Japan as the object of the Hollywood gaze. The film was the first to be shot with rigorous use of découpage,3 while as a beauty in a swimsuit, its star actress Hayama Michiko was a sensation.

Hayama Michiko in Thomas Kurihara’s Amateur Club (1920s).

The experiments of the new generation of Kaeriyama, Osanai, and Tanizaki were all disappointing failures at the box office. The majority of Japanese viewers continued to prefer to cry at shinpa melodramas, moved by the vocal gymnastics of the benshi. Kaeriyama retired from filmmaking in 1924. At Shōchiku, the actor’s training school folded, and the studio quickly returned to making shinpa films, with Nomura Hōtei making maternal melodramas into box office smashes. Tanizaki and Kurihara turned away from Hollywood imitations and were drawn to reviving the world of Japanese pathos, drawing on the works of Izumi Kyōka and the Edo-period writer Ueda Akinari.4 It would be a mistake, however, to see this turn as simply an imitation of Hollywood form that collapsed on account of an intense Japanese tendency toward cultural exclusivity. Western culture, for Japanese intellectuals, was something like what Freud identified as a superego, and the complaints of film critics stopped in pointing out how these films were not American enough. Meanwhile, the public flocked to a flood of Hollywood films, becoming intimate with its cinematic techniques for a time. The Pure Film Movement ended in 1923, in part, because of the Great Kantō Earthquake (関東大地震) of that year that leveled Tokyo. Film studios had no choice but to relocate to Kyoto temporarily, which is to say, to move to the center of kyūgeki. There, in Kyoto, it was not possible for the winds of the avant-garde and modernism to blow as they did in Tokyo.

Even while acknowledging this string of defeats, it is impossible to dismiss the significance of this movement within Japanese cinema. First, the position of the director was established. In addition, it became impossible to rely on onnagata any longer, and their disappearance allowed for the birth of actresses and the star system. With more realism demanded, instead of shinpa and kyūgeki, cinema shifted toward gendaigeki and jidaigeki. Second, film censorship also became strictly regulated. Among other things, this regulation attests to the fact that state authorities no longer saw cinema as merely spectacle or on the same level as theater; instead, they recognized it as a larger medium, with the possibility of influencing large groups of people.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, during the Pure Film Movement, motion pictures (katsudō shashin) became cinema (eiga). That Kaeriyama gave the name “film play” (eiga geki) to the movement marks this transitional moment. At this time, discourses about cinema produced major changes. The film historian Aaron Gerow argues that it was during this movement that a discourse of “Japanese cinema,” rather than simply cinema, first became possible.5 Film critics at the time earnestly debated the differences between true Japanese cinema and a cinema made in Japan that lacked value, consigning kyūgeki, shinpa, rensageki, and benshi to the latter, and announcing a sharp break with them. True Japanese cinema not only must be pure as cinema but also must represent, in transparent form, the true Japan. To be understood by foreigners (i.e., Westerners) and be exported abroad were the barometers of this orientation.

It is said that Kaeriyama made A Story of White Chrysanthemums (Shiragiku monogatari, 1920) at Italy’s request, but this is unclear. The Pure Film Movement, needless to say, contained contradictions. In this film, we see this contradiction as the members of the movement initially evaded a Japanese setting, placing the story in a summer resort and then tried to depend on Western cultural trends, such as shingeki and Christianity. Unresolved, these questions of what constitutes “Japanese-ness” and “cinema” continued to be pressing issues for Kurosawa Akira and Mizoguchi Kenji in the 1950s and extend up to the present moment.

The desire for the export of Japanese cinema abroad led to an oddly warped consciousness surrounding those Japanese people who had traveled to Hollywood during the 1910s. For example, in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Cheat (1915), Hayakawa Sessue performed with an expressionless style peculiar to Kabuki, one that appeared eccentric in the context of the actors around him. Within the world of silent cinema, which was full of frantic and meaningless movement, Hayakawa’s expressionless performance seemed to epitomize the figure of the mysterious and inscrutable Asian. At a time when a firestorm against Japanese immigrants was raging in America, the existence of Hayakawa, with his dangerous black hair, his good looks, and forceful seduction of a white woman, was unique. In Japan, however, The Cheat was judged as an insult to Japan, and to this day, it never has been released officially in Japan. Sessue was forced into a strange, double position in his native land. On one hand, he was criticized for presenting a warped view of the real Japan; on the other hand, he was praised for achieving success in a revered place like America. Kamiyama Sōjin, who went to Hollywood just after, never played a Japanese person there because of Hayakawa’s precedent. Instead, Kamiyama specialized in playing bizarre Arabs or Chinese people, whereas ironically, the roles of Japanese people would come to be played largely by Chinese actors.

After the commotion from the Pure Film Movement died down, all of the film studios seemed to return to the older conventions of shinpa and onnagata. Gradually, however, as the seeds of the movement came to bear fruit, steady changes in style became apparent. Under the direction of the young producer Kido Shirō, Shōchiku started to move in the direction of making bright, cheerful cosmopolitan films. What they sought was the depiction of the everyday lives and human emotions of college students or businessmen as something utterly relatable, rather than the lives of the beautiful elite, as with shinpa. These Shōchiku gendaigeki truly emerged in 1926. Ushihara Kiyohiko shot healthy youth films like He and Tokyo (Kare to Tokyo, 1928) and sport films like King of the Land (Riku no ōja, 1928), both featuring actress Yagumo Emiko. Gosho Heinosuke shot Bride of the Village (Mura no hanayome, 1928) and Dancing Girl of Izu (Izu no odoriko, 1933) starring Tanaka Kinuyo based on the Kawabata novel, but these films were set in the countryside and had a lyrical style. Saitō Torajirō specialized in slapstick: Kid Commotion (Kodakara sōdō, 1935) was laced with gags that approached black humor. Of course, these gendaigeki assembled actors with their distinct performance styles, such as Ryū Chishū, Sakamoto Takeshi, Saitō Tatsuo, and Iida Chōko, but these actors were not marquee stars like those who appeared in jidaigeki.

The light, cheerful mood evident in Shōchiku’s gendaigeki was changing gradually, coming to depict the modest joys of humble city dwellers of shōshimin. The person who most represents this trend was Ozu Yasujirō (1903–1963). Ozu began by making nonsense comedies, strongly influenced by Lubitsch and Vidor, and he initially was derided as “reeking of butter” (overly Westernized). He slowly changed his themes and style, preferring to focus on the sense of resignation and worldviews of life among college students and businessmen as well as common people in ordinary neighborhoods. Typical examples include I Flunked, But (Rakudai wa shita keredo, 1930) and I Was Born, But (Umarete wa mita keredo, 1932). From the low-angle shots and the fixed camera setup, to the uncanny repetition of the characters’ actions, the impulse toward formalism in Ozu’s films is strongly visible. By the 1950s, the rigor of his style had been perfected, and he was hailed as a master.

At Nikkatsu, modernization lagged a step behind that of Shōchiku. Around 1923, at its Mukōjima studio, onnagata still existed, but eventually they were abolished and actresses were accepted. The actresses who gathered at Nikkatsu included the glamorous Sakai Yoneko; the loud, passionate Okada Yoshiko; the pure, sweet Natsukawa Shizue; and the elegant, but strongly spirited Irie Takako. The Nikkatsu contemporary-film division at Mukōjima collapsed in the Great Kantō Earthquake, and they were forced to move the studio to Kyoto. Murata Minoru, who had been at Shōchiku previously, transferred to Nikkatsu, where he made films such as Seisaku’s Wife (Seisaku no tsuma, 1924) and Ashes (Kaijin, 1929). Such films depict the ways that lingering customs and community consciousness in rural families oppress individuals to an inhuman degree. Jack Abe Yutaka, who had returned from Hollywood, successfully combined speedy direction with sophisticated themes in The Woman Who Touched the Leg (Ashi ni sawatta onna, 1926).

The most important director of contemporary films at Nikkatsu was Mizoguchi Kenji (1898–1956). Mizoguchi mastered Hollywood techniques, directing Foggy Harbor (Kiri no minato, 1923) without intertitles, as if carrying on the legacy of the Pure Film Movement. Set in a harbor town and taking the absurdity of fate as its theme, it is the story of a young, well-intentioned sailor who believes he has accidentally committed a murder. Just before that, Mizoguchi had adapted an E. T. A. Hoffman mystery novel and set it in Shanghai with a film called Blood and Spirit (Chi to rei, 1923). The set decoration was based largely on German expressionism, but the film, while full of good ideas, was poorly executed. Mizoguchi had a strong passion for learning and worked across multiple genres with varied techniques; in the 1920s, however, the long-take technique for which he would later be internationally recognized was not yet established, and in this period, each shot was in fact quite short. Scoring a hit with his depiction of working-class emotions in Passions of a Woman Teacher (Kyōren no onna shishō, 1926), he gradually came to turn toward Izumi Kyōka’s world of shinpa, bringing to it a gendaigeki aesthetic.

Kinugasa Teinosuke (1896–1982) was originally an actor as an onnagata at Nikkatsu’s Mukōjima studio, but he freelanced as a result of systemic changes in the industry and came to flourish as a director. In Nichirin (1925), he told the story of Himiko, a queen during the time of Japan’s ancient regime, making use of the Kabuki actor Ichikawa Ennosuke II. By featuring Himiko, a figure not in the official imperial chronicles, this was a challenge to the then-dominant emperor system. The film opened temporarily, but then screenings were canceled. When it finally opened, large parts of the film were cut, and it ended up a box office failure.

After this, Kinugasa started up an independent production company, teaming up with Kawabata Yasunari to direct A Page of Madness (Kurutta ippeiji, 1926). The film tells the story of an aged sailor who has abused his wife to the point of madness. He comes to work as a custodian in the mental hospital where she is held, as a way of atoning for his crimes. Their only daughter is distressed that her lover might find out that her mother is insane. The confused mental state of the mentally ill is repeatedly depicted from their point of view. Kinugasa directed this narrative, which at first glance appears like shinpa, by making striking use of techniques like chiaroscuro, successions of quick cuts, overlap, and bizarre clothes and settings. Although Mizoguchi’s attempts with modernism had mixed results, the approach taken by Kinugasa and Kawabata to German expressionism’s glorification of madness and the grotesque proved quite accomplished. That said, common viewers were unable to follow the narrative, and so ironically, they were compelled to rely on the explanations of the benshi that the Pure Film Movement had worked so hard to banish. Once they did so, however, the film could be understood.

A Page of Madness (dir. Kinugasa Teinosuke, 1926).

We could call A Page of Madness the first authentically avant-garde film made in Japan. Kinugasa followed up this work with Crossways (Jūjiro, 1928), which successfully made use once more of a chain of optical images and warped stage settings through a spinning spherical object. With this experiment, he once more placed vertigo and mental confusion on film. He took the film with him for the next two years through the Soviet Union and Germany. Crossways opened in theaters throughout Europe to high praise. Upon returning, Kinugasa was active as a director of bewitching jidaigeki in the 1930s. Hasegawa Kazuo (whose original acting name was Hayashi Chōjirō) became extremely popular, starring in such Kinugasa jidaigeki as The Revenge of Yukinojō (Yukinojō henge, 1935) and Snake Princess (Hebi hime-sama, 1940), deftly playing both an onnagata star and a handsome male character. As is well known, in the postwar period, Kinugasa’s Gate of Hell (Jigokumon, 1953) would take the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. After that, Kinugasa devoted himself to adapting Izumi Kyōka’s melodramatic novels for film. International distribution was one of the goals of the Pure Film Movement and directors like Mizoguchi and Kinugasa who were members of the next generation achieved the goals of the movement. The personal goals of these directors, however, were set much higher.

At this point, let us take up the trends of jidaigeki in the 1920s.

By the time he appeared in his landmark one thousandth film, Araki Mataemon, for Nikkatsu studios in 1925, Onoe Matsunosuke had maintained his popularity over many years. Throughout that time, however, little by little, changes were rippling beneath the smooth surface of the mega-genre. If the source for jidaigeki had switched at one point from Kabuki to kōdan, in turn, in the mid-1920s, kōdan also yielded to mass literature. This occasioned a switch in jidaigeki, from films as frivolous forms of entertainment for children to films as complex, realistic works worthy of appreciation by adults. The popularity of the conventional sword-fighting style of Matsunosuke, in which he would leisurely cut down his enemies while striking impressive poses, was waning, and viewers came to seek out speedier, more realistic, and more intense sword-fighting styles. Makino Films, which had split from Nikkatsu under the direction of Makino Shōzō, gathered together many directors, writers, and actors to meet this demand. Sandwiched between the big studios, Makino Films was able to produce and distribute films freely as an independent production company between 1923 and 1932. It would be difficult to overstate the significance of this company. It was there that a quite literally radical renovation in jidaigeki took place, giving birth to many stars. These stars followed in the footsteps of Makino, establishing independent production companies in the 1920s and producing films according to their tastes and preferences. Fully half of Kyoto’s shining achievements as one of the crown film cities of Asia could ultimately be attributed to Makino.

Among the actors who gathered at Makino Films, the first to gain popularity for displaying a new type of sword-fighting style was Bandō Tsumasaburō, popularly known as “Bantsuma.” His expression was brutish while at the same time, vibrant, and without a trace of modern melancholy; in particular, he brought a matchless intensity to his portrayal of outlaws, full of despair and expelled to the margins of society. In Futagawa Buntarō’s Orochi (1925),6 he conveyed with extraordinary power the almost masochistic nihilism of a rōnin who sinks to the bottom of society, betrayed by everyone around him. The last swordfight of the film, stretching over ten minutes, remains astonishing even today.

Even Bantsuma was not unique, however, and many other powerful actors are famous for the characters they played in series. Ōkōchi Denjirō, his visage animated by a mixture of rage and dignity, achieved popularity with his portrayal of Tange Sazen, in which his gestures at times verged on the grotesque. Ichikawa Utaemon played The Idle Vassal (Hatamoto taikutsu otoko) in a large-hearted, joyful manner; Arashi Kanjūrō (known as “Arakan”) played the Robin Hood–like figure of Kurama Tengu and the Edo-period detective of Umon in Umon Torimonochō with affection and a blank, Keatonesque expression. Tsukigata Ryūnosuke had a sharp gaze, while Kataoka Chiezō’s performances were laced with his humorous and cheerful demeanor. All these actors lent their trademark characters originality and opened up numerous narrative and staging possibilities in jidaigeki.7 Although characters gave voice to anarchism or nihilism, these films were never subject to the kinds of oppressive censorship gendaigeki suffered; as a result, various social critiques could be expressed even as they were hidden away in its shadows. Of course, bakumatsu mono—films set during the final decades of the Edo period, often extolling devotion to the emperor—were also produced in abundance. One new genre that emerged at the end of the 1920s was mata tabi mono, that is, films based on Hasegawa Shin’s8 stories of wandering gamblers. Tsuji Kichirō’s Kutsukake Tokijirō (1929) and Inagaki Hiroshi’s In Search of Mother (Mabuta no haha, 1932) are two representative films of these Hasegawa Shin stories. The protagonists of the films were lonely yakuza, exhausted by their struggles against authority in cities, who chose a path of wandering. By adhering to nihilism as darkness was spreading in the political sphere, matatabi mono deftly loosened itself from the spellbinding thrall of national community.

Shinpan Ōka Seidan: Kaiketsuhen (dir. Itō Daisuke, 1928).

Two noteworthy directors of jidaigeki during this period, Itō Daisuke (1898–1981) and Makino Masahiro (1908–1993), deserve particular attention. Itō was so fond of dynamic camera movements that he earned the sobriquet Idō Daisuki (“I love movement!”). Although previously it had been sufficient for actors to simply perform their sword-fighting scenes in front of an immobile camera, Itō instead chose to fill the entire screen with fierce fighting. He then sent his cameraman, with a camera strapped to his body, hurling into the fight, having him shoot film as he whirled around within the chaos. The protagonists of his three-part series, Diary of Chūji’s Travels (Chūji tabi nikki, 1927) and his Tange Sazen series (1928–1934) played by Ōkochi Denjirō, were men ostracized by the authorities, struggling for survival, while assailed by feelings of despair and nihilism. In the latter in particular, the protagonist Tange Sazen wields his sword deftly in spite of having only one eye and one arm. Itō’s versions of these stories gained him so much popularity that two different directors would make competing works at the same time based on the same material. Reflecting on this period when the benshi were at their peak, Itō famously declared that, “cinema was never truly silent in Japan.”

Makino Masahiro, the son of Makino Shōzō, resembled a monkey, and so when he was a child, he would play monkey roles in his father’s films. He first sat in the director’s chair himself, just before his father died, making the three-part Samurai Town (Rōningai, 1928–1929). Makino’s detailed portrayal of the passion and anti-authority morals of gloomy rōnin—masterless samurai—earned considerable critical praise, although half of the honor may belong to the scenarist, Yamagami Itarō. In the wake of Orochi, nihilism in jidaigeki was not uncommon, but Makino added a more grounded critical spirit and realism to his depiction of social contradictions. To be sure, many of his works took up the world of samurai, but what informed the basis of his worldview was the existence of ordinary folk, those who reveled at festivals at every opportunity. As a result, whether he was depicting the powerful ruler Oda Nobunaga or Ōishi Kuranosuke, he endowed his samurai with easy-going, amiable personalities, making them largely indistinguishable from common townsfolk.

In bringing to a close this chapter on the mature period of silent film, I must touch on the relationship between left-wing political factions and cinema. In the late 1920s, Japanese intellectuals developed an obsession with communism. The complete works of Marx and Engels were published in Japan even before the Soviet Union or Germany, and Tokyo’s livelier districts were overflowing with youth outfitted in Russian folk costumes. In 1928, the All Japan Proletariat Arts Federation (Nippona Artista Proleta Federacio, NAPF) was formed and the Japanese Proletariat Film Federation (NCPF) was organized along with it. With Sasa Genjū and Iwasaki Akira as its core, the federation shot footage of May Day Parades and labor struggles on nine-and-a-half- and sixteen-millimeter film. The completed films circulated throughout the country in the form of independent screenings. By 1932, state pressure forced the organization called Prokino to become covert, but they continued their activities underground for several more years. As the forerunner for independent film in Japan, Prokino proved a highly valuable endeavor.

Whipped up by the Marx boom and stimulated by Prokino, major film studios during this period produced a number of films that were called “tendency films” (keikō eiga). The term refers to the fact that the films were generally left leaning. In jidaigeki, Itō Daisuke’s Man-Slashing, Horse-Piercing Sword (Zanjin zanbaken, 1929) and Koishi Eiichi’s Challenge (Chōsen, 1930) corresponded to this industrial trend. Challenge, which depicted peasant uprisings, was directed in a way faithful to the vibrant labor struggles and strikes of the time. In gendaigeki, we could cite Uchida Tomu’s Living Doll (Ikeru ningyō, 1929) and Mizoguchi Kenji’s Tokyo March (Tokyo kōshinkyoku, 1929). In the latter, a tennis court atop a hill is contrasted with the slums below through the narration of impressionistic scenes. The most successful tendency film, however, was Suzuki Shigeyoshi’s What Made Her Do It? (Naniga kanojo o sō saseta ka, 1930). An orphan girl is sold off to a circus, and then, after coming to see the tragedies of the proletariat in grinding detail, and the suffering caused by male lust and bourgeois hypocrisy, she is placed in a reform school for girls. Yet even the reform school is full of hypocrisy, so she sets out to burn it down. That the film is tense with the feeling of upheaval can be surmised from a single shot toward the beginning of the film—that of the heroine walking up a diagonal incline alongside a train running likewise along a diagonal horizon.

Tendency films were little more than a short-lived trend. With the beginning of wartime aggression against China in 1931 stoking the rise of nationalism among citizens, tendency films quickly vanished. Once Mizoguchi (who was disdainfully described as “having the political consciousness of a junior high school student”) learned of the establishment of Manchukuo as a Japanese colony, he quickly made The Dawn of the Founding of Manchukuo and Mongolia (Manmō kenkoku no reimei, 1932) and Suzuki shot The Road to Peace in the Orient (Tōyō heiwa no michi, 1938).

For many Japanese cineastes, any kind of political ideology amounted to little more than a surface decoration. Once they had trifled with the newest ideology for a bit, they quickly moved on, switching to something else. In the late 1920s, various film theories—largely from the Soviet Union and France—were introduced, sparking fierce debate among young cineastes over the ideas of Eisenstein, Shklovsky, and Moussinac. This was likely the liveliest moment of film theory in Japan. In 1928, Eisenstein saw a Kabuki play of Chūshingura in Moscow starring Ichikawa Sadanji, finding in it inspiration for new strategies for montage theory.9 Even as the spread of film theories ensured that the position of directors would remain stable, the Japanese, by and large, did not inherit the decisive influence of any single ideology (e.g., Christianity, Tolstoyism, or Marxism). In the 1940s and 1950s, we would come to see the widespread repetition of this tendency ad nauseam.