On the Bwight Side . . .

Adventures in Mistaking Kids for Mini-Adults

When my son Ian was little, I sometimes worried that he was a sociopath. No—wait—let me rephrase that. That’s too strong. I sometimes worried that he was an egotist. Or a narcissist. Or somehow lacked compassion. You see, from the time he could speak until he was three or four years old, when one of his siblings fell down, bruised a knee, or otherwise was physically or emotionally hurt, Ian would remark, unperturbed, “Well, on the bright side, that didn’t happen to me.”

To be completely accurate, due to a speech impediment that prevented him from pronouncing the hard r sound until he was about five, it was, “Well, on the bwight side . . . ”

As I held the injured child, his or her tears soaking through my shirt, Ian regarded the situation, delivered his commentary, and slipped past us. I knew the child in my arms would recover; I was more concerned about Ian. Will he ever learn to be empathetic? How in the world do you teach compassion? Will he ever exhibit concern for the needs of others? If the sight of his baby sister’s skinned knee doesn’t emotionally affect him at age three, will he ever care about the suffering of others?I mean, he had seemed to adore his sister since the moment he first saw her after she was born. Why wasn’t the sight of her tears devastating to him? Later I’d try to get through to him, in a calm yet firm manner. “You know, earlier, when Isabel fell down, it really hurt her.”

“Yah. Hew knee bleeding. She was cwying and cwying and cwying,” he’d observe. “But, on the bwight side—”

“Yes, I understand you’re glad that you aren’t hurt. But Isabel’s feelings matter just as much as yours do. When Isabel gets a scrape, it stings. You can think about how you would feel if it were you.”

“Yah. But it wasn’t me,” he’d clarify, obviously relieved that this was the case.

“But how would it feel if it had been you?” I’d press.

“Guess it would huwt,” he would say with a shrug, and then he’d be on his way.

The next time someone fell off his bike or bemoaned the loss of her favorite stuffed animal, my cheerful little son would once again say, “Well, on the bwight side . . . ” I’d shake my head and wonder what in the world I was going to do to disabuse him of the notion that his were the only feelings in the whole wide world that mattered.

But I need not have worried. A year or two later, I stopped hearing that refrain. When one of his siblings was hurt, he would rush to bring a little treat such as a favorite stuffed animal or a lollipop. “You want to hold Tigey?” he’d ask his sister, offering the comfort of his favorite toy. “Tigey can make you feel better.”

Fast-forward ten years, and Ian is an emotionally intelligent and caring boy. He has a gift for working with children and becomes a one-man vaudeville show when he’s with a young child who is fussing or sad. He throws himself down in pratfalls and makes silly faces that, inevitably, make little children forget whatever was troubling them. Kids delight in being around him, and it’s mutual. He uses this affinity for kids to help others; it’s a gift. A few days ago, for instance, I received an e-mail from the director of children’s ministries at my church. She wanted to let me know how kind Ian had been to a child during Sunday school.

“Ian was sort of a big brother to one of the little boys with special needs,” she wrote. “You would have been proud to see him in action. Just wanted to share that with you, and please pass along my appreciation to him!”

That’s who Mr. “On the Bwight Side” has grown to be.

I wish I’d known in those early years of parenting not to worry so much. I wish I hadn’t seen everything my little ones did as somehow predictive of what they would do as adults.

If she’s telling a lie now, does it mean she’ll perjure herself someday?

If he’s fidgety now, will he never be able to sit through a history lecture in college?

If he’s this obsessed about the ice cream truck, will he end up toothless and morbidly obese, the floor of his house littered with stained Popsicle sticks?

In a Newsweek article titled “In Defense of Children Behaving Badly,” child development expert Po Bronson writes, “It’s widely accepted in our society today that young kids’ behavior is a window into their future. . . . However, it turns out not to be true. One simply must be very careful prematurely judging early childhood behavior.”1

In the story, Bronson cites a study that compared the short- and long-term effects of two different disciplinary styles. Some parents demand obedience from their young children, while others use reasoning tactics in their parenting. Small children who are forced simply to comply with their parents’ orders exhibit better behavior than kids with less authoritarian parents, Bronson writes. However, when the same children are older, the children who were reasoned with reap benefits from their parents’ approach. “Long term, encouraging kids to reason scaffolds complex thought, language development, and independent thinking . . . children of parents who appeal to reason turn out better,” Bronson concludes.

So when your child’s teacher expresses concern that your kindergartner is restless at reading time and doesn’t immediately plop to the floor and sit cross-legged in a box drawn with masking tape on the floor, don’t despair. Explain to your son that being a good listener is important. Perhaps point out that others will be better able to focus on the story if everyone is sitting quietly and still. But don’t decide the boy will never finish high school. It’s way too early to predict such things.

Bronson notes that young children aren’t gifted at reasoning (I want it now! That’s mine!). It would follow, then, that Mr. “On the Bwight Side” wouldn’t be able to put himself in someone else’s shoes either, no matter how often I asked him to do so.

As a young mom, I also sometimes mistakenly thought that my kids’ interests as little children pointed directly at what they’d be drawn to as adults. When he was four, a very stern Theo approached me after we’d gone to the library.

“You need to teach me to read,” he said, gesturing at a pile of picture books. “It’s not fair that you can read and I can’t.”

As previously established, I’m a bit of a book nerd, so his demand came as a pleasant surprise. I went online to find out what I could about teaching kids to read and asked homeschooling friends for their recommendations. In the end, I purchased a book called Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons.2 It was easy! It worked! Theo and I had fun doing the lessons together and although the authors caution parents not to complete more than one lesson of about ten minutes a day with their children, sometimes we sat on the couch going through the book for an hour. Theo insisted that we “Keep going!” By the time we reached the last page of the book a few months later, Theo was reading at second-grade level.

Mission accomplished!

Two years later, when Ian turned four, I sat him down and opened up that trusty manual.

“Good news!” I said. “Today I’m going to start teaching you to read.”

“No, thank you,” he said, sliding off the couch.

“Hold on. Come back up here,” I said, patting the spot beside me. “You see, when you know how to read, you can pick up any book and read it.”

“I like it when you read to me,” he said, sliding down again.

“Oh, yes. Me too! And you and I will still do that, just like I still read to Theo,” I said. “But look how much he loves to read books all on his own too!”

“That’s okay, but I don’t want to do it,” he said.

I finally managed to convince him to read through a lesson with me. Just one! (A bribe of some horse stickers may have been involved.) He sat still, relatively speaking, as I enthusiastically went through the lesson. At the end of it, he asked me if we were done and then slipped away as quickly as possible.

The next day when I asked him if he wanted to do his reading lesson, he shook his head.

“No, thank you. I’m going to go play,” he said.

And that was that.

Now, you might assume—as I did on that day—that while Theo became a wonderful reader, Ian was destined to lag behind his brother. You might wonder, as I did, whether I should have forced Ian to do the next ninety-nine lessons. Perhaps—here I nod to proponents of extreme parenting—you think I should have called him names or withheld his dinner until he agreed to do the reading lessons.

Well. I didn’t.

And guess what?

It worked out just fine.

Although it is true that Theo was reading well when he started kindergarten and it wasn’t until he was in first or second grade that Ian became a full-fledged reader, in time it all evened out. And actually, when given an afternoon with nothing to do, it’s Theo who goes for a run, downloads songs for his iPod, or otherwise occupies himself. Ian is the one who is ten times more likely to flop onto his bed and read a book. (His current passion is reading military history, mostly on World War II. The kid knows more about blitzkrieg tactics and the invasion of Normandy than anyone I know.)

I somehow had come to believe that my sons’ early childhood behavior was, as Bronson describes it, a “window to their adult selves.”3 I thought of them as pocket versions of their adult selves. Of course, they are so much the people they were from birth: Theo’s focused gaze, Ian’s merry spirit, Isabel’s strength, and Mia’s sweet temperament. But every year they come to understand themselves and their place in the world in new and ever more profound ways.

When we think children are mini-adults, we make all sorts of assumptions about childhood. Fortunately, I’ve been disabused of that notion again and again by people who insist that kids are, well, kids. One such truth-teller was Ian’s third-grade teacher. I’d heard rumors about her before learning that he was assigned to her class. She was too laidback, some parents complained. Instead of learning the fifty states and capitals the traditional way (Maine? Augusta! South Dakota? Pierre!), she had her students perform a play. A musical, no less!

I don’t remember much about the play except that the words great and state were rhymed together quite frequently and that one little girl turned green during the performance and I thought she was going to vomit. As soon as I noticed her pallor, I began nudging and “psst”ing at her mother, who didn’t have a clear view of the girl. Other parents scowled at me and thought I was being a rude audience member, but finally I got the mother’s attention, did some rudimentary sign language, and she slipped up the side of the room, pulled her daughter off the risers, and ushered her out of the room.

Just in time, if memory serves.

Anyway, Ian’s teacher told us on curriculum night that if there ever were a day when our children had homework but we were in the mood to take them on a bike ride or play a game with them instead, we should just write a note explaining why the homework wasn’t done.

“They grow up so fast,” she said. “Enjoy your time with them.”

Now before you blame teachers like this one for the downfall of the American economy, you should know that she is a gifted teacher, and I saw Ian grow academically by leaps and bounds that year.

But she was a little . . . nontraditional.

When I mentioned at our parent/teacher conference that Ian’s handwriting seemed sloppy, she looked at me incredulously.

“He’s in third grade,” she said, laughing. “Take it easy, Mom!”

It was, in fact, a relief to have this teacher. I didn’t have to pretend to care about things that I knew were not important. I didn’t have to hustle to make sure this homework sheet or that project was done perfectly. Ian loved going to school, came home bursting with ideas, and when I had the compulsion and energy to take Ian and his siblings to the park after school, I could do so with a clear conscience.

Now if you prefer more of a Tiger Mother parenting model, you might be extending your claws when you hear about his teacher. This was certainly the case for some of my friends. They whispered on the playground about their concerns. What if third grade was meant to be their child’s make-or-break year and it was compromised because of this teacher?

Taking that worry to the next level, one might ask what if, because of an only patchy knowledge of state capitals, one of our kids would someday miss a few points on the SAT and then fail to be admitted to an Ivy League school? What if then he would fail to meet the friend who would have otherwise been the ideal business partner? Meanwhile, thanks to the “Great State” musical, our children will be relegated to community college instead of attending Harvard.

What if?

What if?

What if?

A few nights ago at dinner, Ian told me a story about this teacher. He had learned in school that day that she was one of the first people who taught a young man named Mawi Asgedom4 after his family arrived in the US from Ethiopia. They were refugees, unfamiliar with the language, culture, or educational system. I bet his teacher’s warm, creative classroom was a very good thing for Mawi and his mother! Mawi, Ian said, learned English quickly from this teacher and flourished in her class. Later he graduated from Harvard University and even gave the speech for the graduating class. So, whether or not his third-grade teacher made him write neatly or memorize state capitals, I’m thinking Mawi ended up doing pretty well.

I asked him, “Hey, Ian—what’s the capital of West Virginia?”

“Charleston,” he answered, rapid-fire.

“Delaware?”

“Dover. Why do you ask?”

“Oh, I was just remembering that musical you did in third grade.”

“Fifty Great States,” he said. “Man that was a fun year.”

“You learned a lot,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. “I loved it. And remember how poor Emma almost threw up during the musical? She turned green.”

My friend Mark, when he speaks about his childhood and adolescence, often ends the story by saying, “It takes a long time to grow into who you are.” He knows that. From a chubby kid who sometimes felt invisible, he became a powerful actor and teacher. But he was raised in a time—for better or worse—when children were not viewed as mini-adults but simply as children. Just . . . children. Mark’s words are a reminder to me. This child’s gifts or that one’s weaknesses are not reliable predictors of how they will fare in life. It takes time to grow into who we are.

Our culture, though, points at the naked emperor—also known as the odd way we are deforming childhood—and says, “Ooh. Nice outfit!” But as parents, we can resist that message, point at that silly figure, and say, “Nope. He’s got a whole lot of nothing on.” Kids do keep growing and changing. Kids don’t need to be as serious about their studies in third grade as does a thirty-year-old doctoral candidate. They don’t even have to aspire to attend an Ivy League school.

Now that Theo, my oldest, is in high school and edging up to graduation and the next phase of his life, we talk about college. By fifteen, he was already tired of adults asking him where he was planning to apply. He gathered a few unlikely school names that he has been tempted to use as answers when overeager adults ask him that question.

“Where do I want to go to school? I was thinking about the Colorado School of Mines. Or the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Or maybe Panhandle State.”

When I first started thinking about Theo and college, I fantasized about what it would be like for me if he went to a prestigious university. “Oh, Theo’s away at school this fall,” I’d say, letting out an opulent sigh. “Yale. I’m so happy for him. New Haven is just lovely in the fall.” (Can’t you just see me in my “Go Bulldogs!” sweatshirt?)

“Oh, yes, it is a good school!” I’d say. “He’s a bright boy. You do recall that I taught him to read when he was just four years old.” At that point I’d toss my head, perhaps casually tucking a strand of hair behind my ear.

Luckily for all of us, I knew steering my son toward a school simply because of how it would make me feel to say he went there was a really, really bad idea. And if I have attempted to raise kids who are not obsessed with brand names, who are authentic, and who will seek to serve others with their lives, that would have been just plain wrong. I decided I wanted to do better for him than pushing him toward the college with the biggest name and highest “Aren’t I a successful mom?” quotient.

While browsing at a local bookstore, I happened upon a terrific book called Colleges That Change Lives: 40 Schools That Will Change the Way You Think about College.5 Aha! I thought. This is more like it. In the book, author Loren Pope busts every myth I had always believed to be true about helping my kids choose a college. No, he says, your child doesn’t need to go to an Ivy League school to be successful in life. In fact, none of the Ivies is included among the forty colleges Pope picked as life-changers. He promises that these lesser-known and often smaller schools “will do as much, and usually far more, than any status school to give you the rich, full life.” The best schools, he explains, focus on the aptitude of their graduates, not of the students at the time of their college admission. Such schools understand that kids aren’t “done” at eighteen, but will learn, grow, and mature throughout the college years.6

After reading Pope’s book, I went from wondering whether I was failing Theo as a mom by not pressing him to go to a high prestige school to feeling a sort of wonderful relief that there are many good schools in the US and he will certainly be admitted to one of them whether or not it’s in the Ivy League. The book gives me the freedom, like that wonderful third-grade teacher so many years ago, to let my teenage child be a teenage child. Theo can enjoy high school. He can keep studying hard most of the time (after all, it was Theo himself who said, “What you do most of the time is what matters”) while continuing to give himself room to socialize, play, and just relax. He can go to football games with his friends. Play pick-up soccer games at empty fields around town. Listen to his iPod.

I will help him prepare for the college entrance exam. I will keep insisting that he uses “whom” when he should. (“Object pronoun!”) And when it happens, as it did just last night, when he asks my advice about whether he should take a high school course he’s interested in even if it’s not A level and won’t carry as much weight on his grade point average, I will say, “Yes! Take it!” (The class, by the way, is “The History of Rock & Roll in America.” According to the course catalog, it “provides students with the opportunity to explore the history, creation, and development of Rock & Roll. As music has played an integral role in societies across the globe, Rock & Roll has helped to define American culture over the past century. This course will allow students to discover the history of Rock as they analyze social trends, movements, and events that led to the development of American popular music in the 21st century.” Um, I’d want to take that class if I were him.) The point is, I’m certain that whatever the outcome of his applications in a few years, everything is going to be all right.

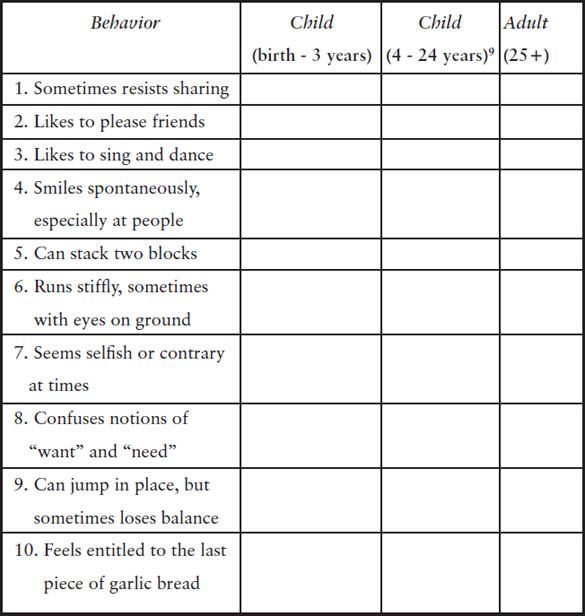

None of my kids is done maturing yet. The human brain just keeps developing. One set of studies says we aren’t truly mature adults until we reach the age of twenty-five.7 Twenty-five!Still, sometimes we expect preschoolers to be empathetic, to be selfless, and even to respond graciously when another child grabs their new sand shovel at the park. Instead of shouting “Mine!” we’d rather they respond like well-bred adults. (“I say, friend. I was just constructing a castle and using that tool. Would you mind returning it to me?”)

No—they wail, grab the shovel back, and possibly fling a little sand in the direction of the perpetrator.

It’s actually a good thing that children start out in life behaving as though their needs are not only the most important ones in the whole world, but the only ones. If babies and toddlers weren’t always bellowing about being hungry, tired, or injured, how would the adults in their lives know to meet these needs? Can you imagine a three-year-old who cut his hand on a piece of broken glass rationally looking at the situation, realizing that it wasn’t a great time to bother his mom while she made dinner, and just let it bleed? Or an infant lying in her crib in need of a clean diaper and dealing with hunger pains but thinking, Oh, I woke them up an hour ago. They must be exhausted! This can wait.

Or a toddler saying, “Oh, hey. I didn’t want to trouble you earlier, but I think I’m allergic to bee stings. My arm has swollen up quite a bit. If you have time later, would you call the pediatrician for me?”

As much as we fantasize about such things on endless, sleep-interrupted nights, it would not be a good thing. No—young kids perceive their hunger, injury, and well-being as the most important things in the world. And that’s how it should be. They are vulnerable. They don’t know how to use a cell phone and take-out menu when they’re hungry. They need our help and protection and care.

By all of this, I’m not saying we shouldn’t engage in the long and, yes, tedious process of teaching them manners, modeling generosity and restraint, and disciplining them for misbehavior. (Throwing sand in the sandbox really is a no-no.) I just mean that we don’t need to think that because they aren’t naturally selfless, they are destined to a solitary, vain life. Or that if they’d rather run and play than do reading lessons when they’re four, they’ll never learn to read. They aren’t fully mature, remember, until they are twenty-five years old!

I know that, despite the fact that a child’s nature will determine much about him or her, parenting does indeed matter. Kids who are connected with their parents do get better grades. They do engage in less risky behavior. They do bring more good to the world. There’s a lot we can’t control, but we can teach our children by word and example how to treat others. We can help them learn to be resilient. We can model to them that they are valuable and that every person deserves their respect. We can praise them for their efforts to do well. We can teach them to seek redemption—in their social and spiritual lives. With our help and in spite of our mistakes, as we parent them with love our children will keep growing and changing, becoming more independent, more empathetic, more the people God has created them to be.

But we don’t really need to teach them to read when they’re four years old.

(Unless, of course, they insist on it.)

. . . and then look at a developmental chart8 to be reminded that it takes time for brains to mature and for kids to learn everything from block-stacking to empathy.

(Um, I don’t know about you, but I checked every box in the 25+ column.)