The Military Expedition which it is necessary to send will gratify and give confidence to all loyal and well-disposed persons. Her Majesty’s troops go forth on an errand of peace, and will serve as an assurance to the inhabitants of the Red River Settlement, and the numerous Indian tribes that occupy the North-West, that they have a place in the regard and the counsels of England, and may rely upon the impartial protection of the British Sceptre.

— Governor General John Young, Address to the House of Commons, May 12, 1870

On January 19, 1870, over 1,000 people gathered on the parade grounds at Fort Garry to hear an address by Donald Smith, the Dominion’s third envoy to the Red River Settlement. After standing in minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit for more than five hours, the attendees reconvened the next day and agreed to send 40 delegates — 20 French, 20 English — to consider “Mr. Smith’s commission” and decide “what would be best for the welfare of the country.” The Convention of Forty set to work confirming a Bill of Rights as the basis for negotiating the terms of union with Canada. On February 7, Smith was invited back to discuss the bill. With no authority to negotiate, though, all Smith could do was invite the convention to send delegates to Ottawa “with a view of effecting a speedy transfer of the Territory to the Dominion.” On February 10, Abbé Ritchot, Judge John Black, and Alfred Scott were chosen to go once the Bill of Rights was finalized.

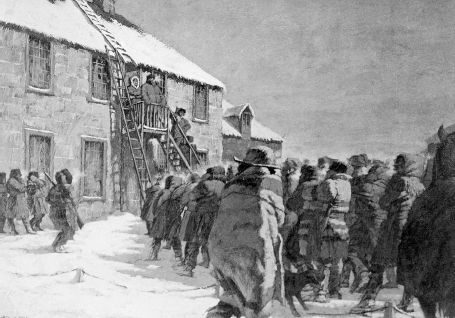

Donald Smith and Louis Riel, Fort Garry, 1870, original painting by Bruce Johnson featured in the 1969 Hudson’s Bay Company calendar. The two leaders address a crowd.

As the diplomacy played out in Red River, the Dominion government began laying the groundwork for a military expedition to the territory as soon as shipping lanes on the Great Lakes were clear of ice in the spring. To this end, Simon Dawson was directed in early January to “increase the force on the Thunder Bay Road” to complete construction of the bridges and the remainder of the roadway “before the opening of navigation.” Dawson dispatched his old friend and colleague, Lindsay Russell from Superior City, to oversee the operation; he travelled the 200 miles to Thunder Bay by snowshoe to take on the job. Dawson also chartered two steamers, the Algoma and Chicora, to ferry men and matériel from Collingwood to Fort William and contracted shipyards in Ontario and Quebec to build 140 boats to convey troops from Lake Superior to Red River. And to secure permission for the expedition to travel across Anishinabe land, the Cabinet appointed two envoys to begin negotiations — Robert Pither, Indian agent at Fort Frances, and Wemyss Simpson, the former HBC factor at Sault Ste. Marie, current Member of Parliament for Algoma, and Molyneux St. John’s future boss.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Macdonald lobbied to have Britain participate in the mission. As Macdonald argued, “It is of great importance that a part of the force should be Regular troops as it will convince the United States Government and people that Her Majesty’s Government have no intention of abandoning this continent.” The prime minister also believed “the insurgents would more readily lay down their arms to a British force than one entirely Canadian — and even in the case of actual resistance, the conflict would not be attended with the same animosity, and after the rising was put down would not leave behind it such feelings of bitterness and humiliation.”1

On February 11, the Cabinet formally asked Britain to participate. London agreed, but with conditions: the force couldn’t be used to suppress the insurgency; British troops — the last remaining in North America — had to be home in Britain by Christmas 1870; and Britain would pay no more than one-quarter of the total cost of the expedition. Canada readily agreed. On February 23, veteran commander James Lindsay was named lieutenant general in charge of organizing the expedition to the Red River Settlement. He arrived in Canada on April 5, but by then the whole point of the mission had shifted.

In early February, the Dominion government agreed to meet the Red River delegates, and with this, Riel’s success was complete. Not only was he able to unite all parties in the settlement behind a common political and constitutional vision but he also got the Dominion government to agree to that vision as the basis for negotiating Red River’s entry into Confederation. It was, in Stanley’s words, Riel’s idée maîtresse.

The achievement still left the problem of the prisoners in the cells of Fort Garry. By February, a few, including John Schultz, Charles Mair, and Thomas Scott, had escaped and made their way to the Canadian enclave at Portage la Prairie, and a few more were released after swearing allegiance to the Provisional Government. On February 10, at the conclusion of the Convention of Forty, Riel agreed to release the remaining prisoners in exchange for English support for a Provisional Government. As a show of good faith, he set three high-profile prisoners free that night — HBC Governor Mactavish, Dr. William Cowan, and businessman Andrew Bannatyne — with assurances the rest would be released over the next day or two. The English delegates agreed, and the Provisional Government was announced. Members included James Ross (judge), Dr. Curtis Bird (coroner), Andrew Bannatyne (postmaster), William O’Donoghue (treasurer), Thomas Bunn (secretary), and Louis Riel (president).

News of the prisoners’ release reached the two streets of Winnipeg almost immediately, but not Portage la Prairie 60 miles distant. Since escaping there in January, Scott, Mair, Schultz, and other “refugees” had busied themselves fomenting discontent among the English-speaking Loyalists. On February 12, a party of 60 men armed with clubs set out for Fort Garry behind Major Charles Boulton with plans to forcibly release the remaining prisoners. The group reached Kildonan, east of Winnipeg, on February 14. A couple of hundred Loyalists rousted out by Schultz joined them there on the 15th to settle on a list of demands. These were relayed to Riel on the 16th and involved release of the prisoners and a general amnesty for all, including Schultz who had a price put on his head. The assembly also informed Riel that several of the English-speaking parishes wouldn’t recognize the Provisional Government, after all, despite their delegates’ commitment to do so just five days earlier.

Riel was furious. He threw the assembly’s messenger, Thomas Norquay, in jail, ripped his letter into pieces, and stormed off. Eventually, Riel calmed down, released Norquay, and sent him back with a message informing the assembly that the last of the prisoners had, in fact, been set free the previous day. He also reminded the assembly of HBC Governor Mactavish’s request that they “for the sake of God, form and complete the Provisional Government. Your representatives have joined us on that ground. Who will now come and destroy Red River Settlement?” Without common cause — or food or lodging — the assembly disbanded and went home.

With nothing to show for their efforts, the last 48 Portage la Prairie men decided to march home as a unit along the main road that passed directly beside the walls of the still-occupied Fort Garry. Fearing they’d be sitting ducks for the Métis troops inside, though, Boulton pleaded with the men to disperse and return individually and quietly through the countryside. But to no avail — the men insisted on returning home as one, heads held high, the bravery they’d marched to Kildonan with intact. On February 17, the group set off westward single file through the thigh-deep snow. And then, just as Boulton feared, when opposite the north gate of the fort, a troop of Métis guards rode out and took them prisoner. Thomas Scott was one of the 48 placed back into Fort Garry’s recently vacated cells.

Riel was incensed — again. He had Boulton put in irons and informed him and three other prisoners, including a belligerent Scott, that they could expect to die the next day for treason. Word of the sentences spread quickly, and a number of Winnipeggers pleaded with Riel for clemency. Donald Smith was ultimately successful on Boulton’s behalf — he was able to negotiate a pardon with Riel in exchange for promising to shore up English support for the Provisional Government.

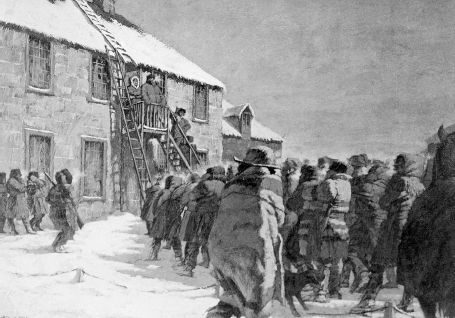

Scott wasn’t so lucky. According to witnesses, the Orangeman attacked his guards, hurled racial insults at them, encouraged his fellow prisoners to do the same, and threatened to kill Riel upon release — even to Riel’s face. To shut him up, two guards dragged Scott from his cell on February 28 and beat him until someone, supposedly a member of the Provisional Government, forced them to stop. And still, despite more warnings and a personal entreaty from Riel for peace, Scott’s rancour boiled. Riel had him placed in irons on March 1 and on the third brought him before a tribunal headed by Ambroise-Didyme Lépine and including André Nault and Elzéar Goulet. The charges against Scott were taking up arms against the Provisional Government and striking his guards. The tribunal heard from Riel and the guards and then discussed the penalty and eventually voted in favour of a death penalty. The next day, Nault and Goulet went to retrieve Scott from his cell where the Reverend George Young was praying with him. Scott, accompanied by Young, was led through the main gate to a firing squad waiting outside the fort to administer the tribunal’s sentence. Five months later, Robert Cunningham wrote the first detailed account of Scott’s murder, a rather hagiographic version based on an exclusive interview with Reverend Young.

Thomas Scott.

Scott’s death ignited a firestorm of rage and indignation across Protestant Ontario — and John Schultz and Charles Mair fanned the flames. Aided by Joseph Monkman and William Drever, Schultz and Mair escaped from Red River sometime in March and made their way to Ontario where George Denison (of Canada First) organized a series of rallies across the province to “express indignation at one of the most cold-blooded murders ever perpetrated” by “that black criminal, Riel,” and his band of “black-hearted aggressors.” The rallies demanded action “from true and sober Volunteers who will travel to Red River and restore peace and maintain the honour of the country.” The first indignation meeting was held in Toronto on April 6. Over 10,000 people packed the square in front of city hall to hear Schultz, Mair, and two other “refugees” regale with tales of being imprisoned “in a room swarming with vermin of no more than twelve feet by fourteen feet. It was more the Black Hole of Calcutta than anything else.” The rally in Toronto, like many of the other indignation meetings that spring, ended by adopting resolutions like this: “That prompt and vigorous measures be taken to bring Riel and his lawless bandits to justice, and that every precaution be taken by the government to protect the lives and liberties of the loyal people of the Territory, and maintain the honour of the Empire.”

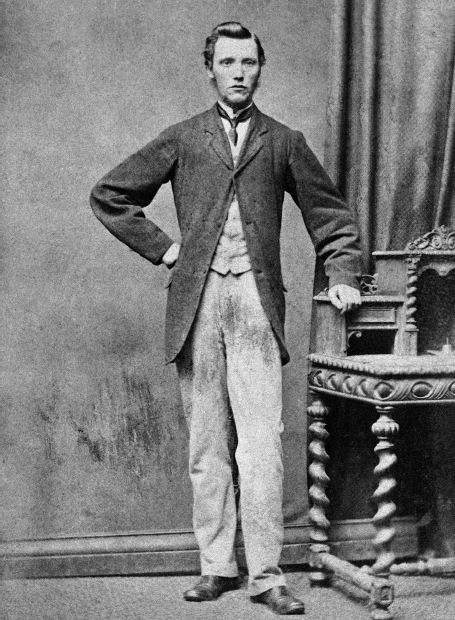

Lieutenant Colonel Garnet Wolseley, Staff, Assistant Quartermaster-General, Montreal, 1866.

With Canada’s second general election looming, the rising tide of indignation across vote-rich Ontario put pressure on Macdonald’s Conservative government to speed up plans for the military expedition, at the very least to get the situation in Red River under control, at best to deliver retribution. The government was ably assisted when Lieutenant General Lindsay arrived in Canada on April 5 to get the military logistics under way. His first task was finding a commander and luckily he didn’t have to look far.

After fighting in the Crimean War and almost losing a leg, Colonel Garnet Wolseley had served in Canada with distinction since 1861, organizing training academies at La Prairie and Thorold, helping to negotiate the terms ending the Fenian invasion at Fort Erie in 1866, and most recently serving as quartermaster-general. The Dominion government agreed with the appointment, and Lindsay next turned to staffing the force. Canada agreed to contribute 705 soldiers raised in two battalions from militia units in Ontario and Quebec and brought up “to the standard of Her Majesty’s Regular Forces” by “strong and drilled” officers “carefully chosen.” Regimental orders to this effect were issued on April 21, and the first Volunteers arrived in Toronto on May 2 for inspection and training. To fulfill its contribution to the mission, Lindsay appointed 19 soldiers from the Royal Artillery, 19 Royal Engineers, and 352 infantry from the 1st Battalion, 60th Rifles, most of whom had been stationed at Toronto that winter. And that was where at least the officers of these units fell under the charm of Kate Ranoe, the international burlesque star.

Despite Lindsay’s efficiency in getting the expedition up and organized, it couldn’t actually leave until negotiations with the Red River delegates were complete. These began on April 25 in Ottawa and finished with the introduction of legislation creating Canada’s fifth province on May 2. As per Red River’s demands, the Manitoba Act provided constitutional guarantees for the French language in both the legislature and courts, publicly funded Roman Catholic schools, representation in the federal Parliament, and 1.4 million acres “for the benefit of the families of the half-breed residents” to be divided “among the children of the half-breed heads of families residing in the Province at the time of the said transfer to Canada.” The Manitoba Act received royal assent on May 12.

As the Manitoba Act was introduced into the House of Commons on May 2, the Algoma was readying to depart from Collingwood on the first trip of the Great Lakes shipping season. On board were 150 labourers Simon Dawson had hired to augment the workforce on the road between Lake Superior and Shebandowan Lake, road-building supplies and equipment, 40 horses, a couple dozen oxen, and 150 or so “deck and cabin passengers.” These included Dawson himself, Wemyss Simpson, and “two special correspondents from Toronto newspapers” who would spend the next five months embedded with the expedition as it wound its way to Red River — and one international burlesque star neither reporter bothered to mention.