Off for Red River once again. The last time I started on a similar expedition, snows and frost prevailed, and the farther north we went the snows and prevailed the more…. I propose going as far as Fort Garry, and hope to have the privilege of saluting my quondam friend Riel under somewhat different circumstances from those in which I saluted him last time.

— Robert Cunningham, “Manitoba in the Distance,” Daily Telegraph, May 4, 1870

We started from Collingwood with considerable éclat. We were not the Red River Expedition exactly, but we were a near relation to it, and though we were none of us soldiers, one of the party wore a military cap with a red band round it, which gave a warlike colour to the affair. We looked like service too, and what we lacked in rank was made up in enthusiasm.

— Molyneux St. John, “The Red River Expedition,” Globe, May 5, 1870

Around eight in the morning on May 3, 1870, Robert Cunningham, Molyneux St. John, and Kate Ranoe boarded a train at the Northern Railway station at the foot of Brock Street in Toronto bound for the tiny port of Collingwood on Georgian Bay. The train was one of many specially contracted by the Canadian government to carry expedition troops and supplies to Collingwood where they would be ferried to Government Station, four miles east of Fort William on the northwest shore of Lake Superior. With the two correspondents were 150 labourers Simon Dawson had hired to work on the road from Thunder Bay to Shebandowan Lake, the starting point for the inland portion of the expedition. St. John said the men were a mix of French-Canadian, Métis, and Indigenous men, including 21 Iroquois from “Caughnawaga” who had been “engaged for service in the boats.”

The trip to Collingwood was relatively short — a quick four hours. The voyage to Thunder Bay would be longer — about 50 hours, not including the time it would take to get through the canal at Sault Ste. Marie. And if the road was in as good shape as Lindsay Russell told Simon Dawson it was, it would only take another two days to reach Shebandowan Lake, the start of the old North West Company canoe route Dawson had mapped out. But from there all bets were off. St. John said no one knew exactly how long it would take to transport Wolseley’s army by canoe through the wilderness of northern Canada to Fort Garry. Maybe a month, maybe three.

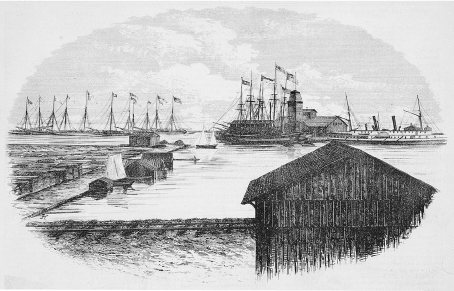

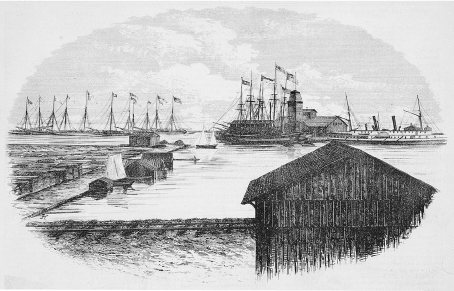

Collingwood Harbour.

At Collingwood, St. John and Cunningham found that a “whirlwind of activity” had descended upon the tiny village. The expedition trains had been running for days and their cargo spilled along the shore and narrow wharf jutting into the bay. Cunningham said the place was “littered” with wagons, horses, oxen, hay, fodder, and all manner of construction equipment such as wheelbarrows, spades, picks, and axes. And boats. A short spur line between the railway terminus and the waterfront was studded with a long line of cars carrying the 140 boats purchased for the expedition. Some were clinkers, lighter vessels built by overlapping — or lapstraking — the hull planks, and others were the heavier, more rigid carvers whose hull planks were laid smoothly edge to edge and fastened to rigid frames. St. John said the clinkers had attracted a fair number of critics who claimed the rough-and-tumble of the portages would cause irreparable damage. The critics also pointed out that the clinkers couldn’t be repaired in the woods the way the carvers could be.

Moored to the wharf were the two steamers Dawson had chartered for the expedition. The smaller of the two was the sidewheeler Algoma. It measured 147 feet long, had a beam of 23 feet, and an impressive registered tonnage of 787. For the past year, the Algoma had been plying the weekly mail route between Collingwood and Bruce Mines. Beside the Algoma was the sleek and graceful Chicora. It, too, was a sidewheeler but measured 221 feet long, had a beam of 26 feet, but only a registered tonnage of 740. The Chicora had started life as a Union blockade runner in the American Civil War, after which it was purchased by Canadian interests and pressed into passenger service between Collingwood and Fort William. “In point of speed and comfort,” Cunningham wrote, “the Chicora may be considered the finest steamer on inland waters.” Over the next six weeks, six more steamers would be pressed into service, as well, along with four schooners, two gunboats, two tugs, and various barges, rafts, and scows. It would be all decks on hand to transport the expedition’s 1,100 troops; 700 voyageurs, guides, scouts, teamsters, and labourers; and thousands of tons of munitions and supplies to Government Station.

The Chicora.

How the Algoma and Chicora were being loaded was evidence of the first major challenge the expedition was about to face. Rumours had been swirling for weeks that the United States would deny expedition vessels passage through its canal at Sault Ste. Marie. Some Americans believed Canada was at a breaking point in the spring of 1870 — financially stressed from the purchase of Rupert’s Land, economically challenged by the impending construction of the Northern Pacific Railway across the northern states, and politically weakened from secessionist pressure in the Maritimes. These Americans believed failure to put down the insurrection in Red River would be the straw to break Confederation’s back. And with that the United States could annex Rupert’s Land and thereby join recently purchased Alaska with the rest of the country. Like an apple ripe from the tree, Canada would fall into American hands. On May 3, Hamilton Fish, the pro-annexation American secretary of state, ordered officials at Sault Ste. Marie to deny canal passage to any foreign military vessel or vessel with military matériel. While the U.S. government wouldn’t meddle directly in Canadian affairs, annexationists weren’t going to sit idly by, either.

As a workaround, expedition officials decided to send only labourers and construction equipment north on the Algoma on May 3. The thinking was that at least Dawson and his crew could go through the canal and proceed to Thunder Bay to get the road finished in time for the troops’ arrival. The Chicora would depart four days later with munitions and other military supplies. Hopefully, that would give diplomats in Ottawa, London, and Washington enough time to figure out how to gain access to the canal.

St. John said it took longer than expected to get everything and everyone aboard the Algoma and properly secured. In addition to Dawson’s crew, 150 “regular passengers” had to be brought on, along with supplies and mail destined for “the survivors of the six-month Lenten period” cut off from civilization by the winter freeze-up on, the Great Lakes. At around 5:00 p.m., the steamer finally cast off into Georgian Bay. Three hundred people crowded the deck to wave farewell to the well-wishers on the shore. Those on board included Simon Dawson, Wemyss Simpson, “two special correspondents from Toronto newspapers,” and “a half-dozen more waifs.” And the international burlesque star.

At around 11:00 p.m., the Algoma “touched” at Owen Sound to land Mr. Wilkes, the proprietor and editor of the Owen Sound Advertiser, and tie up for the night. The ship got under way the next morning and pulled alongside the jetty at Killarney in the early afternoon. St. John described Killarney as a small village made up of a few fishing huts and a “store-cum-post office.” The terrain was largely rock, with a number of fishing nets stretched on the larger ones to dry. As the first steamer of the year to arrive, the Algoma was “heartily received” by the locals who seemed, to Cunningham at least, to be mostly Indigenous women, some Métis men, and a few “non-descripts.” Leaving Killarney, the Algoma passed Little Current, a village the same size as Killarney but where Cunningham heard both the “white man and fire-water” had gained a footing “so effectively that prostitution, debauchery, and misery are rampant.” Just like Stanley Street in Toronto.

The Algoma passed Spanish River later Wednesday night and reached Bruce Mines early the next morning — a “long, straggling village” built on the rocky shore. While the captain tended to postal duties, a number of passengers went ashore to hunt for the area’s renowned copper-streaked rocks. For St. John, the prospect of nifty souvenirs couldn’t outweigh the destitution of the place: “If there be an inhabited spot on the route that looks more uninviting than another, it is the Bruce Mines.”

The next part of the trip made up for the wastelands at Bruce Mines; St. John called it “the most beautiful view of the trip.” Proceeding north on the St. Marys River toward the tip of Sugar Island, they passed Echo Bay and the entrance to Lake George to starboard. St. John said the lake was nestled between two ranges of hills running inland where they met at the far end in a single mountain. It was a dramatic backdrop “situated at such a distance that its colour and apparent density varies from that of the foreground. The openings at the remote end of the enclosing hills admit the light, and cause beautiful gradations of light and shade.” The Algoma slipped to the far side of Echo Bay, and the sun sank toward the horizon into the western sky and turned a fiery red. The colour transformed “all around the western side of the lake and the adjoining land” into “a succession of fantastic shapes in colours varying from pale sea green to deep gold-fringed purple.” And then as the sun dipped lower and lower, the mountain at the far end of Lake George caught the reflection of the richer tints, and “the last remaining light of the day lit up the farther slopes of the receding hills, the inward face of the western range had subsided into the gloom of the evening.” At that moment, St. John said a loon rose to the surface beside the ship, and looking at the “vessel in the sharp indignant-like way peculiar to its kind, rose and took his way into the lake, where uttering his dismal cry, he seemed to call attention to the solitude of his home.”

As the sun went down, the Algoma continued past Sugar Island and the International Raspberry Jam Manufactory, the “epicentre of an extensive raspberry trade” run by Philetus Church. At about 11:00 p.m., the steamer docked at the Canadian village of St. Marys — about 40 or 50 houses, Cunningham estimated, where once again the locals gathered to welcome the first steamer of the year.

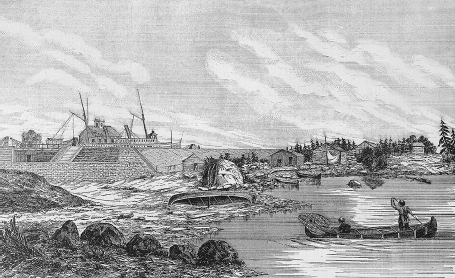

The Chicora passing through the Sault Ste. Marie locks.

Cunningham said no one really slept that night, since they were all eagerly engaged in a debate over the “great question” of whether the Americans would allow the passage of expedition vessels through their canal. Early the next morning, on May 5, with locals assembled on both sides of the rapids, the Algoma steamed through the half-mile waterway “unmolested.” Question answered, the ship set immediate course for Michipicoten Island to drop supplies and was under way to Fort William by mid-morning as if the imbroglio never happened. The Chicora, by contrast, would have an entirely different experience a few days later. Cunningham elected to “remain over at the Sault” to keep readers apprised of the situation; St. John stayed on board the Algoma and reached Thunder Bay early on Sunday morning, May 8. It would be almost a month before the two would meet up again.