There never was a river with a greater disinclination to go in a straight line for ten yards together, and mile after mile was passed with only a few hundred yards gained. The stream, too, was choked with fallen trees and snags, so that at several places it became necessary to hew through large trees before the canoe could pass…. The only comfort derived from this was a dinner of pigeons that I shot from the canoe, and which my travelling companion curried.

— Kate Ranoe and Molyneux St. John, Globe, July 25, 1870

The industry of these women is most remarkable. At daybreak this morning four of the canoes were dancing over the lake in various directions, and in the evening they returned, one with beans, two with a few fish…. If such industry could be taken hold of and directed into other channels, how much comfort might accrue from it, and how much squalor and misery and wretchedness might be banished from the face of the earth.

— Robert Cunningham, Daily Telegraph, July 26, 1870

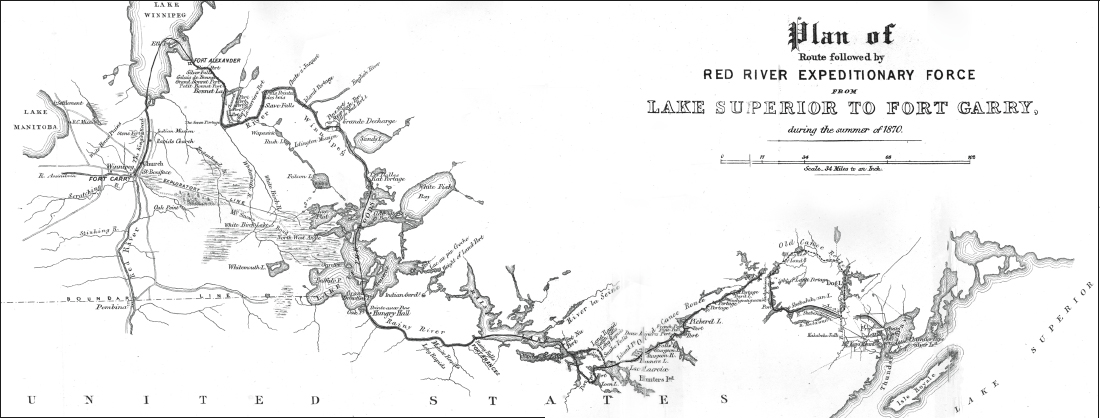

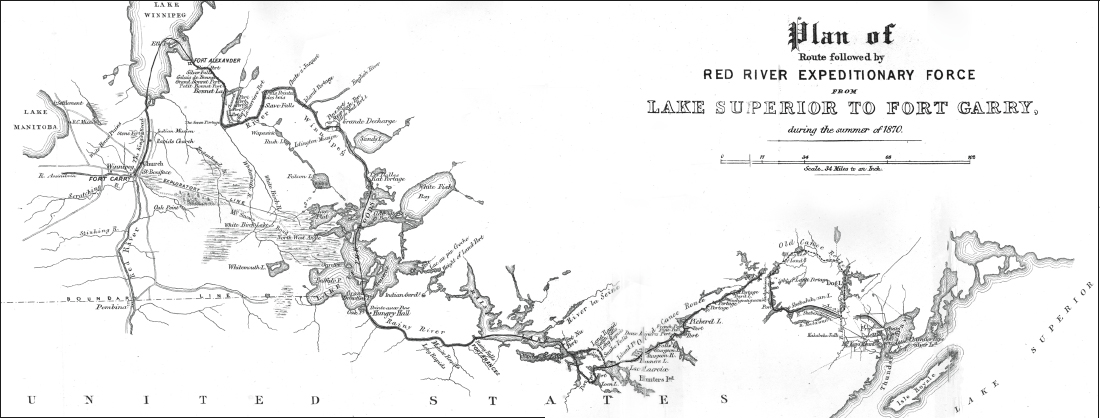

The first part of the journey from Shebandowan Lake to Fort Garry was 208 miles to Fort Frances. This followed the old North West Company canoe route through an area called the Lake Region. It began with 20 miles of paddling across Shebandowan, then three-quarters of a mile across the Kashabonne Portage, paddling eight miles across Kashabowie Lake, then across the one-mile Height of Land Portage and into Lac des Milles Lacs. On a map, this part of the journey was one of the hardest, since the Height of Land Portage represented the high point of the watershed boundary between Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes. Together, the first two portages made up one-quarter of the length of all 46 portages between Shebandowan Lake and Lake Winnipeg. The rest, said the map, was all downstream. “Downstream” from Lac des Milles Lacs, however, involved another 15 portages totalling one and a half miles. These stitched together a long succession of lakes, rivers, streams, ponds, marshes, and bogs before getting to Fort Frances, roughly the halfway point to Fort Garry.

Plan of route from Lake Superior to Fort Garry.

If the expedition seemed extended across Dawson’s 48-mile road during the first two weeks of July, that paled in comparison to the 160 miles it stretched out on August 2. The first boats with the 60th Rifles got under way on July 16, the last on July 21. The Ontario Battalion departed on July 23 and finished five days later. Then came the Quebec Battalion bringing up the rear, the last of which left McNeil’s Bay on August 2.

The main reason the boats were spread so far was to prevent clogging at the portages; built for canoes, only one expedition boat with its dozen men and three and half tons of supplies could get across at a time. By this point, the only thing connecting the expedition was the inter-canoe mail service. As R-SJ described, “Four small canoes are stationed at portages between Shebandowan and Fort Frances and carry the mail bag from one point to the next, where it is taken on by the canoe waiting. The time of departure and arrival is so calculated that under ordinary circumstances a weekly mail service will be in operation between Thunder Bay and here, and by and by, further on.”

St. John and Ranoe set off from McNeil’s Bay on Tuesday, July 18. Cunningham was delayed a day after Waubussy found the pork supply had gone rancid, forcing the reporter to travel back down to the Matawan Bridge depot to buy more. All three were keen to stick as close to the lead boats as possible because they wanted to “enter Fort Garry with the van.” And given the pressure on Wolseley to get the Regulars started back home before freeze-up, the very real possibility existed of the first two detachments pushing on from Fort Frances “without stopping for other detachments.” Neither correspondent would see a Canadian soldier again until after they began arriving at Fort Garry on the evening of August 27.

At the end of Shebandowan Lake, the gruelling labour of the first portage began. The experienced voyageurs used tumplines to haul the heaviest barrels and boxes — some over 300 pounds — the 1,200 yards to Kashabowie Lake. The “less hardy” carried lighter supplies such as biscuits, tea, and camping gear in whatever manner they could, including the modified hand-barrow method where two men transported one barrel between two eight-foot poles, with one man at the rear and the other in the lead. (A few portages on, the barrow method was dropped in favour of tumplines, despite the “perspiration flowing in great drops, and every nerve and muscle quivering as if under the action of a galvanic current.”) Once across the portage, the men went back to skid the boats over greasy green poplar logs placed at three-foot intervals. Here, the Regulars had the advantage of experience: they had learned how to portage the boats on the Kaministiquia and Matawan Rivers, and most of the voyageurs, “many of whom are lads,” had been assigned road duty since arriving at Thunder Bay.

The Globe canoe reached the Height of Land Portage on Thursday, July 21, and started into Lac des Milles Lacs later the same day. Almost 20 miles across, R-SJ said the lake was “so dotted” with islands, “intersecting points and promontories,” and numerous straits formed by “the jutting land” that only three or four miles of open water could be seen at any one time. Not surprising, the topography made the map “incomprehensible,” and the Globe correspondents were soon lost in a landlocked cove they nicknamed Blunder Bay. And they weren’t the only ones. As it turned out, the guides weren’t familiar with this route (most knew the more northerly Dog Lake one), and a number of the Regulars’ boats — those of Lieutenant Colonel W.J. Bolton and Captain Francis Northey — got lost, as well.

By Monday, July 25, things were looking up. Lac des Milles Lacs and the Baril and Brule Portages were to stern, and both the Globe and Telegraph canoes were in Windigoostigwan Lake with the lead brigades of the expedition — Cunningham near the van, St. John and Ranoe bringing up the rear. In the late afternoon, the lead boats reached the western end of Windigoostigwan where it emptied into the French River over a series of small rapids “not seven feet in width” followed by a fall of about 40 feet. After Sagers and Waubussy sussed out a satisfactory line, the Telegraph went first, shot the rapids, and waited in a small pool at the head of the falls for the next boats. Lieutenant Colonel Randle Feilden’s canoe came next. When it reached the pool, the troops unloaded, portaged down past the falls, and pitched camp for the night a bit downriver.

While the Telegraph held at the foot of the rapids, Cunningham and crew received company — seven canoes full of Anishinabe. In the first was “Snow Flake, a chief of the Chippewas,” and seven “younger Flakes.” Cunningham said “old Flake” was smoking so “vociferously” on his pipe that he wondered exactly how much tobacco the man and his family actually smoked in the course of a year. The “young Flakes” had long raven hair arranged “quite touchingly” into neat long braids that fell over their shoulders. The other six canoes were “freighted with as hungry-looking crews as ever sailed on water.”

The Anishinabe canoes surrounded the Telegraph, and a grand powwow, as Cunningham called it, began with Waubussy at the helm. Everyone spoke at once, Waubussy managing to “keep them all going” with a “wonderful, really incredible versatility.” At one point, Snow Flake motioned that he wanted to talk with Cunningham privately. Through Sagers as interpreter, the chief said he was responsible for many people who were starving and wanted Cunningham to give him food. Waubussy and his conversationalists stopped talking to listen in.

“Chief Snow Flake, I am very glad to see you,” Cunningham said. “I hope that you will shake hands with me.”

The chief shook Cunningham’s hand warmly.

“I hope that all your people are in good health,” Cunningham continued.

Through Joe, Snow Flake said they were.

“As to your question of food,” Cunningham said, “I am sorry to find that our stock of provisions are getting fearfully low. Somehow they are diminishing with a celerity that fills me, not only with alarm but with much amazement. In short, I cannot spare anything. If a plug of tobacco, however, would serve in any way to mitigate your and your people’s hunger, you may have it.”

Snow Flake expressed “a thousand thanks,” took the tobacco, and shook Cunningham’s hand once more.

At this point, Lieutenant Colonel Feilden emerged from the portage trail to find out how the boats were proceeding down the rapids. Snow Flake asked Sagers who he was, and Sagers told him the officer was also a chief, whereupon Snow Flake told Feilden through Sagers that he and his people were hungry and needed food.

“I don’t have much to give anybody, but may be able to manage a little,” Feilden said.

And then “such a scamper took place.” The canoes shot across the little inlet “like arrows” and exited the water. The men emptied the canoes, turned them downside up, and scurried off down the portage trail, leaving the women to do the bulk of the work — “packing up the bark and bedding, putting on their packing straps, leaded themselves with a bundle which would have made any ordinary men gross, and each crowning the thing by making the papooses describe a somersault in the air and landing on top of the bundles away they trotted to get something to eat.”

That evening, the Globe canoe reached the end of Windigoostigwan where “shouts and laughter from the soldiers ahead” could be heard through the trees. Despite the darkness, the Globe boat shot the rapids, “bumping ominously” once or twice against the rocks. Then the crew portaged around the falls, re-entered the river, and paddled a short distance around a bend until they came upon Feilden’s camp. The river there was “filled with bathers’ heads and bottoms,” the shore and woods lit bright by the “blaze of camp fires,” shouts and laughter echoing off the rocks and trees. The Globe crew found a place to pitch camp for the night and settled into preparing dinner over the campfire. Afterward, pipes were stuffed and smoked and the day’s run “computed and discussed” until the embers of the fire died down and the night breeze “freshened sufficiently” to keep mosquitoes away. And then everyone sank into the kind of “deep, steady, and refreshing” sleep that can only “succeed a hard day’s voyaging.”

The next day, Tuesday, July 26, Cunningham and the Telegraph canoe set off down the tree-clogged French River (Dawson’s men hadn’t cleared it yet). As they proceeded, wood pigeons flapped up from the riverbank, and Cunningham and mates “kept popping away at them in the most persevering manner.” And they weren’t the only ones — shots could be heard coming from ahead, as well.

Rounding a bend in the river, “the culprits” came into view. Five bark canoes, each containing one “squaw with papoose” and “at least one dog,” were pulled up along shore, evidently on a break. Cunningham said the women were smoking in the “most nonchalant fashion,” enjoying their reflections “mightily.” As the Telegraph boat drew near, Waubussy, “with his best foot forward,” greeted the women and in a minute or two was at the centre of another grand powwow.

Cunningham thought one of the women was the elder of the group. She was “exceedingly clean and tidy,” had a massive string of beads around her neck, was dressed in a “kind of waistcoat,” and was crowned with a “gentleman’s rowdy hat” that had seen better days. Joe introduced the woman as Chief Snow Flake’s wife.

“I am delighted to see you and most happy to make your acquaintance,” Cunningham said, presenting her with a small gift of tobacco, which Mrs. Flake accepted “with delight.”

The Telegraph got under way again, and Cunningham assumed the visit with the women was finished. But no sooner had the Telegraph found the current than the five canoes “wheeled to the right” and “came on in line in the rear.”

Waubussy was “in ecstasy” and kept up a conversation with Mrs. Flake in the lead boat of the flotilla as they paddled along. Cunningham said he felt “a little uncomfortable” leading a convoy of five Anishinabe women but remembered they were in their own territory and “each carried a musket in her canoe.” These, the reporter calculated, made the odds against the Telegraph “considerable.”

At one point, Cunningham asked Sagers if he thought the women were good shots. Sagers gave him a “sarcastic smile” and said something to Mrs. Flake, who laughed likewise, drew up to the bank, and sent her dog into the bush. Not two minutes later, the dog flushed out “quite a flutter of pigeons and partridges.” Each of the women seized a gun and brought down a pigeon. Through Sagers, Mrs. Flake told Cunningham that he was welcome to join in. The reporter did and ended up “bagging four off one tree!” For this, Cunningham gave Mrs. Flake a few beans and then bid farewell once more.

Ranoe and St. John caught up with Cunningham and the Telegraph in the late afternoon at a “pretty little campsite” on a sandy beach. After pitching their tents side by side, the men set a table for dinner on one of the tarpaulins while “my travelling companion” — Ranoe — “curried” some of the pigeons they had shot earlier in the day. Cunningham judged the meal “capital” and the dinner party “very pleasant.” (While the reporters mentioned this dinner in their respective articles, Cunningham made no reference to Ranoe and R-SJ neglected to say Cunningham was present.)

As the sun set that evening, the reporters enjoyed a pipe around the campfire and then turned in for the night. Not long after, Cunningham said he was awakened by “an apparition” peering through the flap. The figure looked human “but not entirely.” The mouth and chin were definitely human, the hair, as well, but not the eyes, nose, or cheeks. These were painted a “deep horrible black.” Cunningham jumped up in fear but said something in the eyes stopped him — they seemed timid, tired, and sad.

The reporter screwed up his courage, threw back the tent flap, and found a young Anishinabe girl about 12 years old standing nearby. In her outstretched hand, she offered a tin of blueberries. Feeling as frightened as she appeared to be, Cunningham took the berries and gave her a coin. She didn’t move. In the moonlight, Cunningham said she looked so hungry, “so pinched was her cheek,” that he went back into his tent and came out with some hardtack.

While the girl ate, Cunningham went to find Sagers and Waubussy. Through Sagers, Waubussy said the girl was an orphan whose parents had recently died. The black face paint was “an Indian custom” used to “signify her sorrow.” Waubussy also said Mrs. Flake had adopted the girl out of the goodness of her heart, which Cunningham said moved him to send over a “modicum of tea.”

At daybreak the next morning, four of the Anishinabe women “danced out over the lake” in their canoes to catch fish for breakfast while a fifth remained in camp, fetching water to boil the fish and begin packing. Cunningham marvelled at the women’s “most remarkable industry.” When the others returned, the fish was cooked and dished out with a wooden fork, “chunks to this one and that,” until all were served. Cunningham didn’t find the meal at all appetizing to look at but did say it had one consolation — “a scientific one” — that fish “by far” is the “most effective nourisher of the brain,” making these women “very intellectual characters, much above the average brain power.”

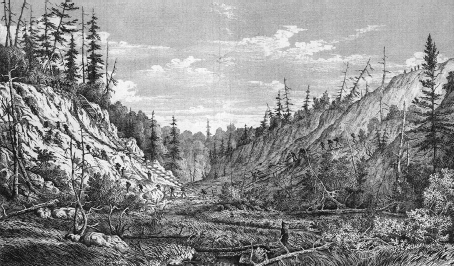

Deux Rivières Portage, on the Red River route.

As the Telegraph crew packed up their own camp, Cunningham turned to Sagers. “Why has Mrs. Flake not cooked the beans I gave her yesterday?”

“She dare not.”

“What do you mean?”

“She cannot eat the beans until Mr. Snow Flake arrives,” Sagers explained.

“But couldn’t she cook them and eat them without Snow Flake knowing anything about it?”

“The papooses would tell,” Sagers replied, closing the matter.

On Friday morning, July 29, the Globe passengers made their way over the “difficult and severe” Deux-Rivières Portage (750 yards) and launched into Sturgeon Lake just behind Wolseley and his officers, Captain George Huyshe and Lieutenant Frederick Denison. The men had their coats off and were blazing the route, using axes to strip bark off strategically located trees to mark a trail for the boats to come. It was a lesson Wolseley had learned the hard way on Lac des Milles Lacs. Not long after the Globe canoe arrived on the lake, a boat came up from the west carrying Wemyss Simpson, the MP for Algoma, and Robert Pither, the Indian agent based at Fort Frances, the Canadian government’s envoys to the Indigenous Peoples of the Northwest. The two had left Fort Frances the day before to update Wolseley on the state of negotiations with the groups prior to his arrival.

Simpson said the chiefs from the tribes around Rainy Lake were adamant that their permission was required for the expedition to pass through their lands and for all subsequent immigrants who were bound to follow. Pither said some of the chiefs threatened to withhold their consent, but he told them, “They might as well try to stop the waters of the river as prevent the troops coming through.” Pither said this was enough for the chiefs to withdraw their objections. Simpson said the matter of permission for the immigrants was left unresolved. They agreed to come back to the issue in formal treaty negotiations to follow in the spring.

Simpson also delivered a letter from Henry Prince, chief of the Saulteaux and Swampies, which R-SJ included in their August 15 story:

LETTER FROM AN INDIAN CHIEF

INDIAN SETTLEMENT, RED RIVER

May 26th, 1870

To the General Commander-in-Chief of the Red River Expedition.

Sir, — Newspaper reports have reached us that an expeditionary force is sent by our great mother the Queen across the great waters to restore peace and order in our hitherto quiet settlement. We condemn all the proceedings that have taken place against the representative of our great mother who was turned back from Pembina, and heartless and brutal murder of one of the innocent Canadians, and the imprisonment and ill treatment of our fellow British subjects, both foreigners and our countrymen.

We have suffered in many ways. Anxious for our families, unable to pursue our usual avocations, poverty and want stared us in the face all winter, endeavouring to maintain our loyalty. We shall be greatly relieved when you arrive in our midst, where we are not only ready to receive you with open arms, but shall be most happy to render you what assistance we can, should you require our services. We have done it last winter to Col Dennis, and will always be ready to do it to any of our great Mother’s representatives.

We say nothing at present with regard to our lands: we have every confidence in the Imperial and Canadian Governments to treat us fairly as soon as can be done. It is well known we were never treated for our lands, either by the late Earl of Selkirk or the Hudson’s Bay Company.

We long to see you come. Come with all possible speed. We shall hail the day that you arrive with your force. You have nothing to doubt or fear from any one tribe of Indians, as well as the Protestant part of the population of the settlement. We ask you to make strict enquiries for the loyal French. A large number have maintained their loyalty at all risks and hazards.

We enclose a copy of the reply we have received from the Vice Consul of the U.S. with regard to the Fenian movement. We have since heard with deep regret that a body of them are waiting on your route to obstruct your way. We hope it is a false rumour.

We will heartily welcome you and your force. Wishing you every success.

Signed, on behalf of the loyal settlers, Saulteaux and Swampies,

I beg to remain,

Your humble and obedient servant,

HENRY PRINCE,

Or MIS-KOO-KE-NEW

Chief of the Saulteaux and Swampies

To R-SJ, Prince’s reference to “a settlement for lands taken on the Red River” was “perfectly just and justifiable,” and similar claims would continue to be made until settled “in some equitable manner.” In a twist of fate, St. John himself would soon be working alongside Simpson and Pither on the negotiation of Treaties 1 and 2.

Finished their briefing, Simpson and Pither pitched in to help Wolseley and his crew blaze trail back to Fort Frances. With tricky sections coming up on Lac La Croix and the eastern end of Rainy Lake that promised to rival Lac des Milles Lacs, Wolseley was glad of the assistance.

On Sunday afternoon, July 31, Wolseley and the lead boats of the Red River expedition reached Maligne River between Lac La Croix and Rainy Lake. A few hundred yards on, they pulled ashore and the guides and soldiers got out to survey the rapids downriver. The military men thought it best to portage around the first couple of sets, but the young Iroquois guides felt confident they could be run, so the boats were unloaded on the shore. Two guides jumped into the first boat — Simpson’s large “north canoe” — and poled into the rushing water, followed by two more guides in the Globe canoe. The larger vessel disappeared down the run easily enough, but the bowman in the Globe stopped the vessel mid-rapid and swung it around, struggling to regain his line in the heavy water. Everyone on the shore thought the canoe “would be lost,” but the guides were able to get “the paddles at work against the rocks” and back the canoe over to the better line. Then, with a “loud Ojibway shout of triumph,” the Globe rushed through the foam and into the small pool of water below. The two boats were brought ashore there, and the rest of the military boats were moved down the rapid in a similar fashion.

The second set of rapids was smaller and was “passed with complete success.” On the third, one of the military boats “engineered across the corner of the rapid in some peculiar manner and came to grief,” but the soldiers were able to repair the vessel “in time to go on that night.”

The fourth set of rapids presented a challenge of a different order. The chute there had a “heavy fall of water” that ended with a “bank of water that rushed along in an angry curl.” It wasn’t a problem for the high-sided military boats to navigate, but for the canoes with their low gunwales, the curl presented a “rather formidable matter to compete with.” The guides walked the length of the rapid a couple of times, “eagerly scanned the rushing, roaring sheet of water,” and eventually decided “with the canoe lightened, they could take her down safely.” Two guides shoved the Globe into the river where the bark vessel “took the current immediately” and shot over the waterfall. It was lost to sight for a few seconds “in the whirl and spray behind,” but then emerged right next to the angry curl, which did indeed spill over the side. Other than “having shipped a quantity of water,” the canoe was untouched. R-SJ were impressed: “When an Indian, after mature consideration, says he can do a thing of this kind, [we] have confidence in his ability to perform that which he undertakes.”

At the end of the river, the little flotilla crossed into the eastern section of the Rainy Lake system where dozens of “interior Indians” — men, women, and children — had gathered on the rocky shores to “see the troops.” All three reporters were struck by the people’s “chronic state of hunger” and said how difficult it was to make them understand Wolseley’s orders forbidding the troops from giving away provisions. And then, just before the entrance to Namakan Lake, the boats came across “a party of the interior Indians” who were “much taken by the appearance of a lady who was accompanying her husband on this journey.” At first, the Anishinabe women kept their distance, pointing the lady out to one another, “amused” by something in the lady’s “dress or appearance.” Eventually, the elder of the group “came and sat down alongside her white sister, and examined her more closely.” Pither offered the woman some tobacco, which she “commenced to eat after the manner of others living in towns and villages.” Satisfied with the gift, the woman left. No sooner was she gone, though, “than another came and sat down under cover of the umbrella which the Englishwoman had raised.”

The encounter put R-SJ in a reflective mood. They said many of the Hudson’s Bay men believed the interior Indians “incapable of work” and “entirely unamenable” to any instruction, education, or advice. R-SJ thought this “ridiculous,” since the Hudson’s Bay men were well known not to have “any great desire to improve the natives of the interior.” If they did, the results would “now be different” because whatever the people’s faults, “a want of intelligence is not one of them.” To R-SJ, the problem boiled down to the fact that the HBC needed Indigenous people to remain in a state of “semi-serfdom.” Any effort to educate or train the people would only serve to impair their utility as “cheap hunters” or “out-door servants.” R-SJ were hopeful that the sale of Rupert’s Land and the forced transition of the HBC into a competitive trading market would remove some of the obstacles to betterment, since “there is very little of which an Indian is not capable if properly taught and governed.”