We danced over the water and down into the troughs of the sea, keeping pace with the boats that were running under two large square sails, and at midday had passed the Grand Traverse, and many miles, as well, without incurring the fate that had been prophesied for us.

— Kate Ranoe and Molyneux St. John, Globe, August 12, 1870

After leaving the mouth of the Winnipeg River, which entered the lake a mile below the fort, we entered into the southeast corner of Winnipeg Lake itself…. And to look back and see the forty-five boats with all sail out and all in Indian file tripping it gracefully over the somewhat rough sea was a sight worth looking at, and certainly the like of which these waters never saw before.

— Robert Cunningham, Daily Telegraph, August 22, 1870

The route from Fort Frances to Fort Garry had four stages: Rainy River, Lake of the Woods, Winnipeg River, and Red River. The first stage, Rainy River, was relatively straightforward — a “languid and lazy” paddle down to Lake of the Woods, about 70 miles. To Cunningham’s eye, the river was a relatively “broad stream” varying in width between 300 to 400 yards, with the edges crowded thickly with “reeds, bulrushes, and wild grasses,” and had only three portages. The lead boats of the expedition, with the Globe and Telegraph canoes close behind, reached the end of the Rainy on Sunday, August 7.

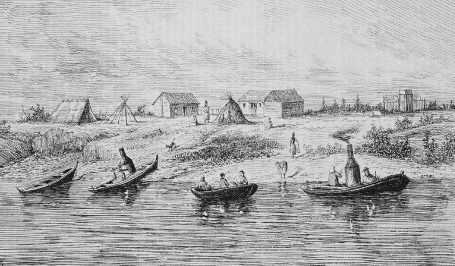

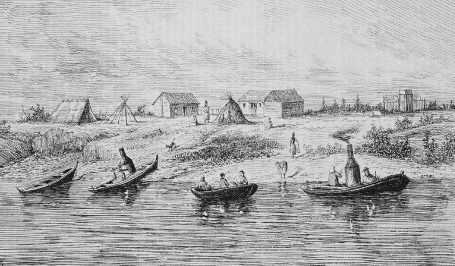

Hungry Hollow Station for tugs at the mouth of Rainy River.

The second stage of the route involved getting across massive Lake of the Woods — 75 miles long, 70 wide, four and a half times the size of Rainy Lake, the largest body of water the expedition had navigated so far. Since Thunder Bay, the challenge of crossing the great open body of water loomed large in the troops’ minds and was amped up at Fort Frances where Anishinabe guides said the crossing would be difficult, since most of the time the boats would be “out of sight of land, with wide stretches of water to the north, south, and west, and the breeze coming on in a moment, raising waves like trees.” They said it would be near impossible for the lighter canoes.

Early on the morning of August 7, the lead boats and the Telegraph and Globe canoes struck out from the dilapidated American trading post Fort Louisa in “a moment of fine weather.” Within an hour, though, the vaunted breeze came up and stiffened by the minute until it was blowing so hard that “had we then been ashore we should not have started.” But they weren’t, and the Globe crew tried to capitalize by setting a good-sized sail and “a large umbrella.” This carried the canoe “over the tops of waves in a marvellous manner,” flying out ahead of the “long, heavy columns” of water rolling up behind and occasionally shipping over the bow and rear gunwales. As they flew along, R-SJ remembered a second umbrella Wolseley had loaned them and quickly set it “as a studding sail.” The light barque craft now fairly “danced over the water and down into the troughs of the sea, keeping pace with the boats that were running under two large square sails.” Four days of fair sailing allowed the boats to traverse Lake of the Woods to its most northern point at Rat Portage “without incurring the fate that had been prophesied for us.”

To help with the intricacy of the lakes, islands, falls, and false passages, Simon Dawson, the Dominion engineer, brought in special guides from the Red River Settlement with local knowledge. These men arrived during the evening of August 8 — but quite by surprise. Cunningham said that a small canoe came around a point slightly downstream from the boats and “without any apparent reason” quickly turned around, paddled back upstream, and disappeared around the point again. The canoe caught the troops’ attention. It wasn’t like the other Anishinabe canoes they had encountered thus far, since it was filled with men both “red and white.”

It was the troops’ worst fear — “Riel’s advance guard were upon them.”

The Regulars pulled hard on the oars in quick pursuit. They rounded the point and spotted the canoe speeding back toward two larger boats. The strangers saw them, too, and began “shouting and discharging their firearms.” A couple of officers drew their revolvers, and one of the expedition boats made off to shore to unload pork, flour, and tea in order to get at the arms chest.

Just as quickly as the threat came on, it dissipated. As it turned out, the “firing and shouting were only a salute and welcome” from the guides Dawson had brought in from the Red River Settlement.

The third stage of the route from Fort Frances to Fort Garry was the 164-mile-long Winnipeg River, by all accounts the most difficult stretch the expedition would navigate. R-SJ said that calling the Winnipeg “a river” was “a mere matter of fancy on the part of the geographer who did it.” In reality, the watercourse was a succession of lakes — some larger than those east of Fort Frances — connected by various chutes, falls, and rapids that descended a total of 340 feet from start to finish. In all, the map said there were 27 portages studding the river; R-SJ expected the number was probably closer to 30 because they had heard that “three of the rapids are so much like falls that they are very seldom ‘jumped.’”

The first day of the journey down the Winnipeg on August 11 was for the most part through “smooth water” with only “some short rapids” at Les Dalles, which were run. On the second day, the portaging and rapids shooting began in earnest. At a place called the Grande Discharge, the river narrowed through three deep, heavy chutes. The Globe canoe fell behind the others here and ended up taking the wrong chute down. It came through into a “broad sheet of water” ending at an even larger rapid that one of the Globe guides refused to shoot. R-SJ tried reasoning with him, pointing out that “even the lady in the boat was not afraid to go.” The guide wouldn’t budge, so the crew had to find a way back to the main route.

On August 14, the head of the armada arrived at Island Portage, one of the largest on the Winnipeg. Here, the guides held a “great consultation” concerning the “feasibility of the boats running the chute.” The chute in question was short and fast, winding through a narrow passage that squirrelled alongside the larger rapid. One of the younger Iroquois guides volunteered to run it and off he went down the rush of water, emerging unscathed, “if not a little wet,” from the roiling waters at the bottom. Not to be outdone, some of the braver soldiers stepped forward to take their boats through, as well, with “everyone on shore congregated on the rocks” to watch and raise a shout as each “swept out of the rush into the eddy.”

From Island Portage, the route became drudgery again, one portage after another, at some places the water stretching for several miles, at others only 100 yards before the boats had to be hauled out just after they were put in. At one point on Sept Portage, an officer missed a turn and ended up with his boat stuck against a large rock in the middle of the rapid. When he was unable to dislodge his craft either by pole or paddle, the strong current threatened to stave in its hull. The officer tried to lighten the boat by dumping overboard the pork, flour, tea barrels, tin cans, and whatever other articles he could get his hands on, while his crew scurried to retrieve the bobbing contents from the eddy downstream. Just as the officer clutched the arms chest, a boatload of guides drifted up from behind and shoved him off the rock, much to everyone’s relief.

On Wednesday, August 17, the lead boats and reporters’ canoes reached Fort Alexander on the southeast shore of Lake Winnipeg. The men’s first priority, as at Fort Frances, was to ransack the Hudson’s Bay store. R-SJ reported that “every available article was quickly purchased” — handkerchiefs, knives, sashes, nightcaps, hats, and “a hundred things besides.” Cunningham thought the frenzy was “not so much that the articles were absolutely required” but merely “on account of the luxury of spending a little money.”

The British soldiers arrived in succession over the next three days and enjoyed “the relaxation granted them here wonderfully.” For the first time in almost six weeks, the men could get up in the morning, “loll on the green sward,” and not have to think of reloading the boats with barrels of pork, flour, tea, and everything else. All revelled in the fresh beef, new potatoes, and buttermilk. Only men who had been in the bush for six weeks and on rations could appreciate and savour every bit of these provisions. Cunningham said that the men were in great spirits and good health, not one accident having occurred to them, “excepting one of the Red River half-breeds.” At one of the portages, this unfortunate voyageur was hauling a pork barrel when he slipped on one of the skids. The barrel “fearfully crushed” the fellow’s leg and he was “left behind with a man in charge of him.”

For Cunningham, the “greatest attraction” at Fort Alexander was the “immense number of dogs” that congregated there. These weren’t stray curs who had wandered in to steal food from the fort; they were trained dogs “employed in winter for drawing sleds” that spent their summers doing nothing except “loafing, fighting, howling, and stealing” to pass the time until seasonal work began again. And they weren’t quiet. Inevitably, at night, one of the “brutes” would start up the nightly concert with a “dismal howling,” keeping at it until “all of them have taken up the wail” in the fashion of their “Esquimaux ancestors.” The concert didn’t detract from the affection the men felt for the mutts, nor the mutts for the men, since “some of the favourites” had become “perceptibly fat already.” The mutts, not the men.

By Friday, the steady arrival of troops (six companies by then) lent Fort Alexander a more military appearance — “something of a respectable and somewhat more lively aspect,” wrote Cunningham. That afternoon, the officers had the men parade and gave them a thorough inspection. While most of the “arms and accoutrement” were found to be shipshape and generally in decent condition given the “amount of knocking about they have gone through,” the troops’ uniforms were showing signs of wear. Some articles — shirts, jackets, pants — had been “torn to shreds by stumps and barrels.” It wasn’t a big deal, but some of the men did think it unfair that the clothing given to them was the same “had they remained in garrison.”

The Regulars kept coming in throughout Saturday, August 20 — Captain Francis Northey’s company first in the late morning, and then around 5:00 p.m., “a large canoe hove in sight.” Cunningham said “the greatest excitement prevailed in camp.” If it was Wolseley, it meant they would be under way to Fort Garry in a matter of hours. Slowly, the canoe “crept in range of the glasses” and then cries of “It’s the colonel!” resounded all around. When Wolseley pulled himself onto the wharf, the Regulars gave him three loud cheers.

After a short conference with his officers, Wolseley issued orders for the Regulars to start for Fort Garry the next day at 3:00 p.m. With only 65 miles to go, Cunningham thought there was “every probability that Fort Garry will witness the arrival of the ‘Army of Peace’ in two days.” R-SJ said that Wolseley held off leaving until Sunday afternoon because he had promised the first two companies of Ontario Volunteers (those of Captains Cook and Scott) that he would wait at Fort Alexander “half a day after the arrival of the last of the 60th” for them to catch up and accompany the Regulars into Fort Garry. All the Regulars, including Wolseley, were impressed with the Ontario Battalion’s “pluck and soldiery ability” and thought its participation in the final advance would “add much to the moral results of the entry — looking at it from a Canadian point of view — and probably would prevent a taunt which may be thrown in our face many days hence.”

At 10:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 21, the bugle sounded for church parade. Four hundred and fourteen Regulars, “neatly got up in their regular military attire,” formed a quadrangle with Wolseley and his staff on the east side. Prayers were read by Father Finn, the resident priest, and Reverend Joseph Phelps Gardiner from St. Andrew’s Parish, who had arrived with the Hudson’s Bay guides on August 8. Gardiner preached “an eloquent sermon” on the theme of “To him that over-cometh,” and at the conclusion, an “excellent band, partly vocal and partly instrumental,” sang hymns “to the delight of all.”

After a quick lunch, the men of the 60th Rifles began preparations to embark on the last phase of their journey: “The boats were loaded — cooking utensils and clothes were packed — last of all the tents were struck.” R-SJ said that Wolseley held off leaving until the last moment, but with no Ontario Battalion boats in sight, and the pressure of his timetable increasing by the hour, the Regulars’ boats slid off the shore and into Lake Winnipeg at 4:00 p.m. Cunningham said that the dogs were the saddest for the departure and “made their feelings known with loud howling.” Near the head of the armada, Cunningham looked back and saw the 45 expedition boats “with all sail out and all in Indian file tripping it gracefully over the somewhat rough sea.” The Regulars, together with the Globe and Telegraph canoes, paddled 14 miles to Elk Island and camped there for the night.