With this Bill in one hand, and the flag of our country in the other, we can enter, not as conquerors, but as pacificators, and we shall satisfy the people there that we have no selfish object of our own to accomplish, that we go there for their good as well as for our good.

— Adams Archibald, Debate on the Manitoba Bill, May 1870

While Molyneux St. John was fighting fires on the shores of Thunder Bay back in May, Adams Archibald, Member of Parliament for Colchester, Nova Scotia, was named lieutenant governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had distinguished himself in debate over the Manitoba Act with calls for compassion and tolerance in the Red River Settlement. He agreed that law and order needed to be re-established and the “supremacy of the national flag” vindicated. But rather than establish military rule, as many indignant Ontarians were righteously demanding, the lanky and likable Nova Scotian argued that the Dominion had a “stern duty” to show all residents “their fears are unfounded, that their rights shall be guaranteed, their property held sacred, and that they shall be secured in all the privileges and advantages which belong to them.” The speech impressed many, including George-Étienne Cartier. In the wake of the debacle of William McDougall’s appointment as lieutenant governor, Cartier believed the new man in that position had to be independent from local affairs. Governor General John Young swore Archibald in at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, on July 27. Two weeks later, he and Young travelled by special train to Collingwood where they and 60 “excursionists” boarded the Chicora for Thunder Bay. Just before departing, Young addressed the “townspeople and farmers of Nottawasaga” and described Archibald’s task as “indeed an arduous one.” But he said he felt the new lieutenant governor’s “calm judgment and tried ability” would guarantee “the unhappy differences of the past will be forgotten and that all classes will unite in the furtherance of the common good, and in the innocent rivalries of peaceful industry.” On August 12, Young saw Archibald off from Shebandowan Lake for Fort Garry, 10 days behind the Quebec Battalion.

Sir Adams Archibald.

Until Archibald arrived, Wolseley’s orders regarding civil authority in the settlement were clear: the laws of Rupert’s Land, and the authority of the Hudson’s Bay Company to administer those laws, were to remain in force. Wolseley’s own authority was limited to command of the expeditionary force. And so Wolseley asked Donald Smith at Fort Alexander to assume the role of acting governor of Assiniboia until Archibald arrived. Riel’s departure and evident collapse of the Provisional Government simplified this decision: to him, there was no other authority to turn to.

Almost immediately, the fragile arrangement was put to the test. As Lieutenant Alleyne’s men searched Fort Garry for arms and men on August 24, R-SJ said that a group of “loyalists” arrived and asked Wolseley to issue warrants for the arrest of “Riel, O’Donoghue, and others on charges of false imprisonment.” Wolseley deferred to Smith, who issued the warrants “under the older form of the judiciary,” but was unable to execute without willing and able magistrates. Cunningham said that as fast as Smith swore in special constables, they resigned “one after the other, as fast as they are called upon to act.” Cunningham ascribed the resignations to “a fear of Riel and his friends.”

This was the first symptom of what R-SJ described as “an entire absence of all law and executive” in the period leading up to Archibald’s arrival. In Cunningham’s words, “as far as law, order, and government is concerned, [Wolseley] is trusting to luck and getting on as best he can.”

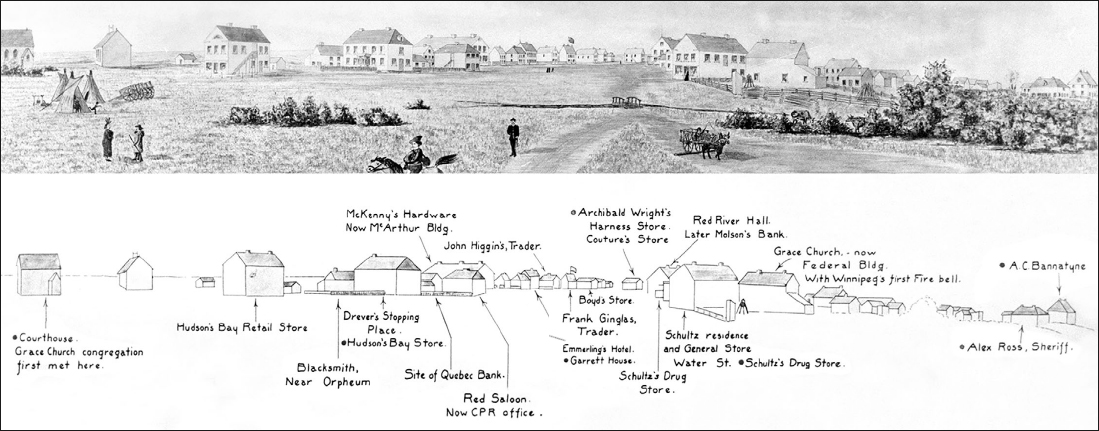

Some time after taking control of Fort Garry on Wednesday, August 24, the soldiers, voyageurs, scouts, and guides were paid. With cash in hand, a large number went into Winnipeg to drink and debauch. As Cunningham wrote, “It was so long since the men had tasted liquor that all who could, troops or voyageurs, went off to make up for lost time.” In short order, the “Winnipeg liquor” succeeded in “overturning the strongest head and demoralizing the steadiest legs” and the muddy streets were filled “with recumbent figures sandwiched in Winnipeg earth.” Cunningham explained: when the drunken men fell down, “one side became a large cake of mud,” and when they struggled to regain their footing, they inevitably fell over on the other side sheathing it in mud, as well. On Thursday morning, Cunningham reported the 600-hundred-yard road between Winnipeg and Fort Garry to be “fairly populated” with bleary-eyed troops and voyageurs “encased in thick, hard coatings” from which they were “with difficulty released.”

Main Street, Winnipeg, 1870.

On Wednesday night, Cunningham also reported the assault of Father François Xavier Kavanagh of St. Francis Xavier by “someone on horseback.” Travelling from Winnipeg to White Horse Plains, the stranger asked Kavanagh, “Who the devil is out on the road so late?” Kavanagh identified himself and the “highwayman” shouted back, “Damn your eyes, take that!” and fired his pistol into the air, causing Kavanagh to fall off his horse and injure his arm.

The expedition men set out from Fort Garry again on Thursday afternoon to assault the taverns and saloons of Winnipeg, but Wolseley ordered guards out to bring them in. Wolseley’s authority, though, extended only to the troops — Cunningham said the voyageurs, scouts, and guides persisted in being “hopelessly drunk.” On Friday morning, the road between Winnipeg and the fort was again “strewn with sleeping beauties” who had “fallen by the wayside in two’s and three’s and there lay regardless of gibes, kicks, and in fact all mundane considerations.”

While the beauties slept on Friday morning, Bishop Taché crossed the river from St. Boniface to meet with Donald Smith and Wolseley at Fort Garry. R-SJ said that Taché wanted to discuss the “great fear” the French-speaking residents had about the impending arrival of the Ontario Volunteers and the “difficulties” they expected with them. He also wanted to discuss reports that a priest “had been shot at.” Wolseley responded by issuing orders prohibiting his officers from “going out shooting.” Smith responded, as well, issuing a proclamation on Monday, August 29, banning the sale of liquor between 7:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. and posting special constables in the village to help keep the peace. By that point, R-SJ said that prohibition wasn’t necessary, since “the liquor is fortunately coming to an end, the price is high, and money is beginning to be scarce.”

In Winnipeg, Cunningham reported that “utter confusion” continued on Friday night when Alfred Scott, one of the three delegates sent to Ottawa to negotiate Red River’s entry into Confederation in the spring, was “taken by the heels and dragged through the mud of the principal street of Winnipeg.” By Saturday, Cunningham said, the English residents of Red River had become disgusted with Wolseley. They insisted he “had no authority in the country whatever — that he had no authority even to retain prisoners taken — that he had no authority to capture Riel.” The French-speaking Métis voted with their feet. According to Cunningham, “The French half-breeds have scarcely shown themselves at all in Winnipeg since the arrival of the troops.” And evidently for good reason: those few who had come into town “have got soundly drubbed,” making “police arrangements” for the protection of these “kindly, simple people” who were without crops, furs, or prospects for the coming winter “much called for.”

The first companies of Ontario soldiers began arriving at Fort Garry in the evening of Saturday, August 27. The next morning, the Regulars commenced preparations to leave, starting on Monday. Wolseley had the following address read to the Regulars at the church service on Sunday:

Fort Garry, August 28th, 1870

To the Regular Troops of the Red River Expeditionary Force:

I cannot permit Col. Feilden and you to start upon your return journey to Canada without thanking you for having enabled me to carry out the Lieut.-General’s orders so successfully.

You have endured excessive fatigue in the performance of a service that for its arduous nature will bear comparison with any previous military expedition. In coming here from Prince Arthur’s Landing, you have traversed a distance of upwards of 600 miles. Your labours began with those common at the outset of all campaigns — namely, road-making and construction of defensive works. Then followed the arduous duty of taking the boats up a height of 800 feet, along 50 miles of river, full of rapids and numerous portages. From the time you left Shebandowan Lake until Fort Garry was reached, your labour at the oar has been incessant from daybreak to dark every day. Forty-seven portages were got over, entailing the unparalleled exertion of carrying the boats, guns, ammunition, stores, and provisions over a total distance of upwards of 15,000 yards. It may be said that the whole journey has been made through a wilderness, where, as no supplies of any sort were to be had, everything had to be taken with you in the boats.

I have throughout viewed with pleasure the manner in which the officers have vied with their men in carrying heavy loads. I feel proud of being in command of officers who so well know how to set a good example, and of men who evince such eagerness in following it.

Rain has fallen upon 45 days out of the 94 that have passed by since we landed at Thunder Bay, and upon many occasions officers and men have been wet for days together. There has not been the slightest murmur of discontent heard from any one. It may be confidently asserted that no force has ever had to endure more continuous labour, and it may be as truthfully said that no men on service have been better behaved or more cheerful under their trials arising from exposure to inclement weather, excessive fatigue, and the annoyance caused by flies.

There has been a total absence of crime amongst you, during your advance to Fort Garry, and I feel confident that your conduct during the return journey will be as creditable to you in every respect.

The leaders of the banditti who recently oppressed Her Majesty’s loyal subjects in the Red River Settlement having fled as you advanced upon the Fort, leaving their guns and a large quantity of arms and ammunition behind them, the primary object of the Expedition has been peaceably accomplished. Although you have not, therefore, had an opportunity of gaining glory, you can carry back with you into the daily routine of garrison life the conviction that you have done good service to the State, and have proved that no extent of intervening wilderness, no matter how great may be its difficulties, whether by land or water, can enable men to commit murder, or to rebel against Her Majesty’s authority, with impunity.

(Signed)

G.J. WOLSELEY, Colonel

Commanding Red River Expeditionary Force

Fort Garry, 28th August, 1870

(Signed) Geo. Huyshe, Captain

On Monday morning, “in the quietest manner possible,” Captains Calderon and Wallace readied to depart with their companies back down the Red River. The only glitch was the reluctance of a certain black bear to board Wallace’s boat. At some point, someone had given the beast to Wallace as a gift and Wallace’s crew was adamant it could be harnessed to help haul the boats across the portages. R-SJ reported that the bear exhibited “the greatest disinclination” to get in Wallace’s boat and “coercion being accompanied with the probability of serious personal inconveniences, no man felt any great anxiety to become bear leader.” With time ticking by, a few “brave souls” tried to coax the creature aboard, but it got free and “a chase through the camp immediately ensued.” Eventually, the troops cornered the bear and somehow inveigled it aboard. R-SJ said that the bear looked “very miserable and uncomfortable as the boat shoved off, but not more so than the voyageur whose duty in the bow compelled him to sit by the side of the strange passenger.”

The Regulars staggered their departure over the week — the last of them left on Friday, September 2, and the Artillery and Engineers on Saturday. By this point, all the Ontario Battalion was at Fort Garry and most of the Quebec Battalion was at Stone Fort. R-SJ said that the Volunteers were “very free from serious illness, and as soldiers, are in capital order.”

After September 3, the only British troops remaining in Red River were Wolseley and his staff — Lieutenant Colonel W.J. Bolton, Lieutenant James Alleyne, Lieutenant Heneage, Assistant Controller Matthew Bell Irvine, and Assistant Commissary George Alfred Jolly. They intended to stay another week to see Archibald installed and finalize winter arrangements for the Volunteers (contract for provisions, ensure construction of winter quarters was completed, instruct the Volunteers “at gun drill,” et cetera). And then this last group planned to take John Snow’s road to the North-West Angle and catch up with the rest of the battalion on Lake of the Woods. Bolton rode out on September 3 to see how far Snow’s men had progressed. For the most part, he found the road in decent shape — “a capital prairie road” for 78 miles, but afterward, 33 miles “more of woods, mud, and brûlée that offer the most formidable obstacles to a through journey.” Bolton was optimistic that the route would be “passable” in a week or 10 days after the crews “opened up with axe and spade.”

On September 7, Bolton left Fort Garry with a group that included Kate Ranoe. Back in Toronto a month later, she would describe this part of the journey in an exclusive for the Globe (see “A Lady’s Journal”). Wolseley caught up with this group on September 11.