Although differing from him on many questions of public policy, we must acknowledge the energy and ability [that Cunningham] brought to bear on all questions that he took in hand, and the consistency of his courses in dealing with them. He did not allow the exigencies of a party or the necessities of a political leader to divert him from the course he had laid out for himself; and to this may perhaps be attributed much of the opposition that he encountered in his political career.

— Manitoba Free Press, July 1874

“Sweet Kate Ranoe” was a toast, a theme for many a callow muse, the goddess at whose feet the habitués of box, pit, and gallery worshipped, the good fairy of the box office…. Pretty, petite, shapely, graceful, charming in every mood and action, blessed with a sweet voice of rare flexibility, she was the incarnation of comedy.

— Victoria Home Journal, August 1893

The late Mr. St. John was a man of versatility, and his career was an eventful one.

— Globe, February 1904

Robert Cunningham, Molyneux St. John, and Kate Ranoe were early pioneers of embedded journalism. They canoed over the same rapids, traversed the same portages, ate the same pork and tack, were bitten by the same sandflies and mosquitoes, faced the same diplomatic and military threats, and experienced first-hand the repercussions of military action on a local population. But while these challenges provided great content for coverage of the expedition, the experience did something more — it embedded them directly and significantly into the lifeblood of their adopted country.

In one of his last posts for the Telegraph, Cunningham said that a new paper called The Manitoban had started up — “the first number displays talent.” The talent, in part, was his. In October 1870, Cunningham and William Coldwell, a former colleague from the Globe, formed a partnership and purchased the printing plant previously used to produce the Nor’-Wester and New Nation.1

The inaugural edition of The Manitoban hit the two streets of Winnipeg on October 15, 1870. Cunningham and Coldwell told readers that their “course” would be “plain and decided. We shall yield to none.” As for the “remarkable interlude” in the recent history of Red River, they condemned “the conduct of the men who usurped authority lawlessly to imprison loyal British subjects and ruthlessly committed murder” but stressed The Manitoban wouldn’t dwell on those events. Rather, the editors promised to consider it “in the light of history” and vowed to do all in their power “to strengthen the hands of the new government in these endeavours to secure law and order, to consolidate the institutions of the country, and to develop the resources of the province.”

It is unclear if Archibald intended to curry The Manitoban’s support when he gave Cunningham and Coldwell the contract as Queen’s Printer in October 1870. If the lieutenant governor did, he accrued significant return on his investment. Over the fall of 1870, Cunningham and Coldwell worked hard as part of Archibald’s “central committee” of supporters, travelling throughout the English-speaking parishes to get a slate of like-minded candidates elected in Manitoba’s first election in December. Cunningham, together with moderates such as James Ross, Alexander Begg, and Andrew Bannatyne, urged electors to co-operate with French-speaking parishes and support Archibald’s policy of “letting bygones be bygones.” Their message was simple: “Archibald’s policy deserved approval, and the united people of the new province should look to the future and elect only men with a stake in the country’s future.”2 Of Archibald’s committee, only James Ross attended more campaign meetings that fall — eight versus Cunningham’s seven.3

By the summer of 1871, Cunningham’s — and The Manitoban’s — support for Archibald’s conciliation efforts extended to strong and loud avocation for Riel’s amnesty and the fair and prompt settlement of Métis land claims under the Manitoba Act. In May 1871, The Manitoban published this:

There are no rebels properly so-called in this Province, and there never were above half a dozen, even in the palmiest days of Riel’s rule. The few who were disloyal were newcomers who had brought their anti-British feelings with them, and joined in Riel’s movement for reasons peculiar to themselves. Riel himself, it is well known, never pronounced against British supremacy, he always hoisted the British flag, but objected to Canada taking possession of this country without giving its people the right to pronounce on the intended absorption. How was it then, it might be asked, that, having only this object — which is legitimate in itself — he went on to rob, imprison and murder? Our belief is that these half-dozen rascals had the principal hand in these excesses, their intention being to create such a breach between this country and England as could not be healed without a big row, in the course of which the United States might find occasion to step in and have a say.4

Quite a change from Cunningham’s first reports of Riel in January 1870.5

Cunningham’s commitment to conciliation and advocacy of Métis rights earned him broad support from both English and French moderates in Manitoba — enough to run in the federal riding of Marquette in the 1872 election. The Manitoban, not surprisingly, backed Cunningham, declaring he had “almost immediately after settling in this country devoted himself to securing the rights of the half-breeds and old settlers as against those who in Canada would have deprived them, if they could, of what had been promised.”6 By this time, Louis Riel was one of Cunningham’s friends and supporters: he came out of hiding to serve as a returning officer. That poll went solidly Cunningham, 339 to 10. Not all were happy with the election results. According to Coldwell, after news of the results hit the streets, The Manitoban’s office “was wrecked by a mob who (intending perhaps to be quite impartial) also wrecked the offices of the Nor’Wester and The Métis.”7

In the spring of 1873, Métis leaders — Bishop Taché, Abbé Ritchot, Louis Riel, and others — sought Cunningham’s help with fixing how lands were being disbursed to Métis families under section 31 of the Manitoba Act. By that time, the Dominion government was using a lottery system. Unfortunately, the prospect of quick cash encouraged many adult Métis to sell their and their children’s rights to participate in the lottery.8 To discourage the practice, Métis leaders asked Cunningham to move a motion in Parliament9 to have the Dominion government follow the strict wording of section 31, which granted lands only to children of the family heads and not the heads of families.10 The motion moved Prime Minister Macdonald to make the change via order-in-council.11

In Parliament, Cunningham continued to advocate for amnesty for Riel. In a speech given in March 1873, he said:

Riel had been pronounced a murderer. He might be so and he might not, but this everyone knew that no man had a right to be called a murderer until he was proved to be. Louis Riel had given every opportunity to be tried, but no sworn information had ever been made before any magistrate in Red River charging Riel with murder. He himself at a public meeting was accused of having refused to grant a warrant for Riel’s arrest. He offered on the spot to sign a warrant if any man would step forward and swear to an information, but no man did so neither then nor since.

With regard to the amnesty, he firmly believed that amnesty was promised. He believed that on various grounds. The Government had given no indication on this point; everything was quiet respecting it; but he had authority which he could not dispute and which he could not question that that amnesty was promised by more members of the Government than one, by Lord Lisgar, and by Sir Edward Thornton at Washington. As the amnesty was granted he held it ought to be acted on, in order that the honour of Canada and England might be maintained. The honour of both countries was involved, and if it had been promised something decisive ought to be done to remove the cloud which continued to hang over the Province in consequence of this matter.

If something were done one way or the other, the wranglings, bickerings, quarrels and listlessness which prevailed in that country would disappear; and these people who before had lived so happily, so peacefully and so undisturbed, would once more enjoy the comfortable existence they had enjoyed before Canadian connection commenced.12

Again, quite a difference from Cunningham’s first reports from Red River.

The Métis community relied on Cunningham in private matters, as well. In correspondence with Cunningham in the spring of 1873, Bishop Taché told the Marquette MP: “I this morning had the visit of Mrs. Goulet who is confident that you will be kind enough to plead before the government the cause of the unfortunate orphans left destitute by the murder of the late Goulet. I know your appreciation of the sad occurrence, so I had no hesitation in assuring Mrs. Goulet that you will have spared no efforts in this matter.”13

In June, Cunningham telegraphed Taché from Ottawa to suggest that he persuade Riel to run in the by-election triggered by the surprise death of Sir George-Étienne Cartier.14 Riel “seized on the idea” and began his campaign in Provencher with broad support from moderates such as Cunningham, Marc-Amable Girard, Joseph Royal, Andrew Bannatyne — and even Donald Smith.

The Métis were appreciative of Cunningham’s efforts. When he returned home in July 1873, the community in St. Vital thanked him for his work and told him his name was “written for ever in our grateful memory.” Riel also bid Cunningham “a hearty welcome home” and thanked him for “your manly stand in the House of Commons, your successes, as well as what you have done for the country in general, and the Métis population of the province…. In devoting your energy to the cause of the Métis children you have earned the general approval of the Métis heads of families.”15

Riel was elected to the House of Commons on October 11, 1873.16 His supporters, including Cunningham, contributed funds to defray Riel’s costs of travelling to Ottawa to take his seat. Riel did travel to Ottawa, but fearing arrest only took the oath of allegiance and signed the roll in the clerk’s office in March 1874. In a vote immediately after, Riel was expelled from the House of Commons by a majority of 56.

Back in Ottawa after an easy re-election in January 1874, Cunningham promoted a number of local causes: construction of a rail line between Pembina and Fort Garry, construction of a rail bridge over the Assiniboine River, and incorporation of the City of Winnipeg. And then, in April, he was appointed to the Council of the North-West Territories.17 The Manitoba Free Press, a persistent critic of Cunningham’s, wondered what qualified him — “certainly not any peculiar fitness for the position; not as a complement to the old settlers, because he is not one; and we are very certain that the new settlers that esteem it such cannot be found.” The Press could only surmise that “perhaps it is because he is the stout defender of the rebels of murderers of ’69–’70; or because he has laboured to the utmost of his ability to do injustice to the English-speaking people of the province, particularly the new settlers.”18

En route from Ottawa to attend his first council meeting, Cunningham died suddenly at St. Paul, Minnesota, on Saturday, July 4, 1874. According to the St. Paul Daily Press, on Friday morning, July 3, Cunningham “was taken with a severe hemorrhage of the lungs, which was so prolonged, and the loss of blood so great, that notwithstanding the kindest care and the most skillful medical attention, he sank very rapidly and expired Saturday morning.” The Globe wrote that while Cunningham would be remembered by his friends “as having possessed many amiable and genial qualities,” his public career was “marred by a certain infirmity of purpose that placed him at times in positions his better instincts would have avoided.”19 Alexander Begg and Walter Nursey were more charitable. They said news of Cunningham’s death “was received alike by all classes of the community, independent of politics or creed, with sincere manifestations of regret. Mr. Cunningham was a brilliant journalist, and the newspaper world sustained in his early demise, an acknowledged loss.”20 At his family’s request, Robert Cunningham was buried in Oakland Cemetery in St. Paul.

To his dying day, Cunningham advocated for his friend, Louis Riel. In an interview for the New York Herald published just a couple of weeks before he died, Cunningham said the death of Thomas Scott “was an unfortunate act,” but when the “whole circumstances” of that period were considered, “there is not a single case in the history of the world that can be instanced where a people went through such a crisis with less bloodshed than what is called the Red River Rebellion of 1869. Notwithstanding all that, the cry for vengeance is more intense in Canada today than it was three years ago.”21

Robert Cunningham, Member of Parliament for Marquette, Manitoba.

The feelings between the two men were mutual. In a poem he wrote three years after Cunningham’s death, Riel told his good friend, Joseph Dubuc, that the former Telegraph reporter was mon vrai Cunningham.22 In 1874, Louis Riel left for exile in the United States, eventually settling in Montana with a wife and family and where he worked as a teacher. Ten years later, Gabriel Dumont convinced Riel to return to Saskatchewan to help resolve a long list of Métis and settler grievances against the Canadian government. Many of these echoed the grievances that had sparked the Red River Rebellion 15 years earlier. Frustrated with the federal government’s inaction, Riel and his supporters announced the creation of a provisional government on March 19, 1885. One week later, the North-West Rebellion broke out with a skirmish between Métis forces and the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) at Duck Lake. The rebellion ended after three days of fierce fighting near Batoche on May 12. “Cold and forlorn,” Riel surrendered to NWMP scouts on May 15. Riel was charged and convicted of the crime of high treason in the summer of 1885. After two unsuccessful appeals, he was hanged at the NWMP barracks in Regina on November 16, 1885, “meeting his death with dignity, calmness, and courage.”

Like Robert Cunningham, Molyneux St. John owed Adams Archibald much in building a life and career in post-expedition Manitoba. Days before his last article for the Globe appeared on October 22, 1870, St. John was contracted by Archibald to examine and report back on issues key to his gubernatorial mandate, including the state of titles to land in Manitoba and the disputed terms of the Selkirk Treaty, how best to appropriate lands for the Métis grant under section 31 of the Manitoba Act, and an assessment of “factors bearing on land settlement” in the new province. In his spare time that fall, St. John also ran for office as a government candidate in Manitoba’s first provincial election in the riding of St. James. He lost 35 to 21 to Opposition candidate Edwin Bourke.

St. John reported back to Archibald in January 187123 and evidently the lieutenant governor was pleased enough to appoint him clerk of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly in March 1871, and then in July, secretary to newly appointed Indian Commissioner Wemyss Simpson.24 That appointment came just in time for St. John to accompany Archibald and Simpson to Stone Fort to negotiate Treaty 1 with the Anishinabe and Swampy Cree. On August 3, 1871, St. John affixed his signature to Treaty 1 as witness. Later that month, St. John accompanied the team to Manitoba Post on the northwest shore of Lake Manitoba to negotiate Treaty 2 with the Chippewa and Cree. Treaty 2 was completed on August 21, 1871, with St. John again signing as witness.25

Archibald continued to shower patronage on St. John throughout 1871 and 1872. Appointments included member of Manitoba’s first Board of Education, superintendent of Protestant Schools and secretary of the Protestant Section of the Education Board, attorney-at-law for Manitoba, justice of the peace for Selkirk County, and Chair of the Manitoba Agricultural Association.26 At these, the Manitoba Liberal — a harsh critic of Archibald’s — asked: “Now, will anyone wonder that the duties of some of these offices must be neglected? We can see no earthly reason why all the offices in this country should be showered on one or two individuals, while we have dozens of men better capable of discharging the duties of some of them.”27

Adams Archibald’s resignation in 1872 caused St. John to search for a new patron, and in July of that year, he found one — Wemyss Simpson appointed him Indian agent and assistant to himself as Indian commissioner. St. John retained the position when Joseph-Alfred-Norbert Provencher replaced Simpson in early 1873.28 In September, St. John accompanied Provencher, Manitoba Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris, Robert Pither (still Indian agent at Fort Frances), and Simon Dawson (now Member of Parliament for Algoma) to the North-West Angle on Lake of the Woods to begin negotiation of Treaty 3 with the Saulteaux.29 After lengthy and at times difficult discussions, Treaty 3 was concluded on October 13, 1873, with St. John once more signing as witness.

Provencher and St. John didn’t see eye to eye; St. John supposedly “expressed some resentment at being passed over for the position himself.”30 In July 1874, he resigned as Indian agent and in November became managing editor of a new paper in Winnipeg, The Standard.31 There was speculation that the new owners included Donald Smith, who wanted a newspaper to advocate passage of the Pacific Railway through Winnipeg and construction of a north–south Pembina Branch to connect Winnipeg to the Northern Pacific south of the border.32 Smith got a good return on his investment: The Standard campaigned strongly for both initiatives, as did St. John personally when he ran in the 1874 provincial election (he lost again) and in his role as co-chair of the Manitoba Railway Committee in the winter of 1875.33

St. John’s tenure with The Standard didn’t last long. In April 1875, the paper was merged with the Manitoba Free Press, and St. John moved back to Toronto where he rejoined the Globe.34 A year later, he was appointed special correspondent again, this time to cover Governor General Lord and Lady Dufferin’s trip to British Columbia. The point of Dufferin’s mission was to assure British Columbians that the Dominion government intended to follow through on its commitment to build a transcontinental rail line as per the Terms of Union. St. John left Ottawa with Dufferin and his party on July 31. They travelled by rail to Chicago and then on to San Francisco where they boarded a Pacific Mail Company steamer to Esquimalt. After spending a few days in Victoria, they sailed up the coast to Haida Gwaii, crossed to Fort Simpson (near present-day Prince Rupert), came back down to the Fraser River, and proceeded inland as far as Kamloops. Dufferin and his entourage returned to Victoria in mid-September, where Dufferin addressed Government House on September 20. Dufferin and his party returned to Ottawa in October.35

Between July and October 1876, St. John filed 25 stories for the Globe and later published them as The Sea of Mountains: An Account of Lord Dufferin’s Tour Through British Columbia in 1876. In one of the more outstanding passages, St. John described a Haida village on Skidegate Bay, Graham Island:

The village consists of about forty houses, each of which contains several families, as we found to be the case in most of these Indian settlements, and these houses are built in one continuous line, some little distance above high water mark. There are a few smaller houses or storehouses behind the others, but that which attracts the eye and rivets the attention at once, is the array of carved cedar pillars and crested monuments that rise in profusion throughout the length of the village. In the centre of the front face of every house was an upright pillar of cedar, generally about forty feet high, and from two to three feet in diameter. From base to top these pillars had been made to take the forms of animals and birds, and huge grotesque human figures, resembling somewhat the colossal figures recovered by the excavation at Nineveh. The birds and reptiles, curious and unlike as they were any that the Indians themselves see, one could understand; but there were griffins and other fabulous animals represented, that one would have imagined the carvers thereof had never heard of. The carvings were in some places elaborate, and in many places coloured. Some of the pillars a few yards in front of the houses were surmounted by life-size representations of birds or animals, the token of the family, coloured in a fanciful manner. In one or two instances there were outline carvings on a board surmounting a pillar, as a picture might be set on the top of a post. The main and tallest pillars, however, were those of which one formed the centre of each house, and through which entrance was had into the interior. Many of the rafters of the houses protruded beyond the eaves, and terminated in some grotesque piece of carving. The Indians could not tell the age of this village, nor had they any tradition on the subject, so far as we could discover. The village must, however, be some hundreds of years old, for the cedar rafters in some houses were crumbling to pieces, and cedar lasts for centuries. Many of the pillars bore signs of being very old, but they are usually sound. Indian villages are usually so essentially only places of shelter against inclement weather, that the appearance of an Indian town of such indisputable age and with such evidences of dexterity in a branch of art, gave rise to endless wonderment and surmise. Whence did the Hydahs obtain the models from which they have copied, since they never could have seen what they carved about their dwellings? One of the party purchased a walking-stick with a small piece of workmanship on the handle, but the Indians passed it about amongst themselves, and none could tell what animal it was intended to represent. It seemed as if the parentage of the carving may have been in China, for one or two of the squatting figures had the same leer on their countenances that one sometimes sees on the figures in a Chinese Joss House.36

In the fall of 1876, St. John left the Globe for the last time and moved back to Winnipeg where he was made sheriff of the North-West Territories. Twelve months later, he was appointed interim Indian superintendent of the Manitoba Superintendency after Provencher was dismissed for administrative incompetence, fraud, corruption, and dereliction of duty.37 St. John resigned in July 1879 when John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives returned to power and undertook a wholesale reorganization of the Department of Indian Affairs under Edward Dewdney.38

Over the next 15 years, St. John continued to churn through appointments and contracts. In 1880, he moved to London to work for fellow Winnipegger Alexander Begg at the Canadian Pacific Syndicate office promoting immigration to the Canadian Prairies. One estimate had the volume of literature produced by Begg’s office amounting “to over a million pieces within a period of six months. Through the London office, the company advertised regularly in 167 journals in Great Britain and in 147 continental papers.39 Two years later, St. John moved to Montreal to become the director of the Land Corporation of Canada (LCC), one of a couple of dozen companies that had received charters from the Dominion government to purchase land from the Canadian Pacific Railway and resell it for colonization. In 1884, shares in LCC went bust, and St. John offered himself as scapegoat to the board; a majority of directors agreed and voted down St. John’s re-election bid 11 votes to 9. In 1887, St. John returned to the newspaper business as editor of the Montreal Herald and president of the Ottawa Press Gallery in 1889. Two years later, he returned to the Canadian Pacific Railway as superintendent of advertising.

After returning to central Canada in the fall of 1870, Kate Ranoe turned up only a couple of times in the newspapers. One story had her in Winnipeg in January 1871, attending the inaugural session of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly and Winnipeg’s “first great ball.” In the fall of 1871, another had her taking over the lease of the Theatre Royal in Montreal and attracting “large audiences” during what one writer called “the Ranoe season.” In 1873, Ranoe was reported back in Winnipeg; three years later, she was starring in productions in Toronto, Hamilton, and Washington, D.C.; and in 1877, she topped the bill in “a new drama written by her husband” at the Opera House in Toronto. The last record of Ranoe and St. John’s theatrical partnership is from March 1878 when “a dramatic performance of some pretensions took place at Pelly [Manitoba] and achieved a most complete success.” The play was Estranged, its author “our Mr. Sheriff St. John,” and the production was “under Mrs. St. John’s directions, and thus her own experience and the author’s intentions were happily united.”40

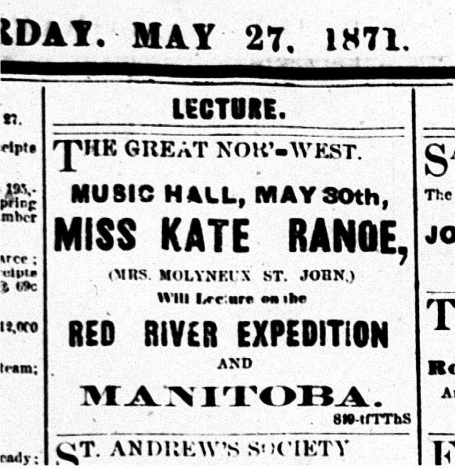

Ranoe gained most attention for a lecture she delivered around Southern Ontario in 1871. It was called “The Great North-West” and premiered at Toronto’s Musical Hall in May. According to reviews in the Globe and Telegraph,41 the evening went as follows.

Advertisement for “The Great North-West” lecture.

Shortly after 8:00 p.m., Samuel Harman, the former mayor of Toronto and long-time alderman for St. Andrew’s Ward, took the stage and introduced himself as chair for the evening. Harman welcomed the “fashionable audience” and complimented the “courage and spirit” that Ranoe exhibited in accompanying her husband on the “Abyssinia-like” expedition to Red River.

Ranoe then rose and walked to the podium at centre stage. She was “handsomely attired in a lemon-coloured silk dress, with tulle overskirt, and with a coronet of gold wheat on her head.” The crowd offered “hearty applause,” and Ranoe waited a moment to begin her three-part lecture.

When the applause subsided, she launched in, starting with the “early history of the Red River Settlements” in which she explained the differences between the English and French to be “on account of their nationality and religion.” She described the period of “benevolent and paternal” rule by the Hudson’s Bay Company, an “anomaly” that she said stood in the way of “opening up settlement in the Great North-West.” The actress followed with an exposition on the “events connected with the recent insurrection,” maintaining that the death of Thomas Scott had to be “ascribed chiefly to the evil influence of [William] O’Donoghue” and was “generally disapproved by the French population.” Ranoe “expressed satisfaction” with the fact that the “only sentiment which survived that period of disturbance and trouble was expressed in a demand for justice upon the murderers of one man instead of vengeance upon many.”

The second part of “The Great North-West” dealt with the expedition itself. Ranoe discussed her reasons for joining her husband on the trip and the difficulties she encountered “overcoming the objections raised against her accompanying the expedition.” While not documented by the reviewers, Ranoe described these “with humour.” She then sought to enlist “the sympathy of her auditors in her adventures as one of the voyagers in the Globe canoe.” She took the audience on the trip up the Kaministiquia River and from Shebandowan Lake to Winnipeg and relayed in graphic detail “the picturesque scenery of the route.” Ranoe also recounted the enthusiasm and “readiness of the Volunteers to undertake the difficult expedition” and the many “difficulties overcome by the troops.” The actress ended her account of the expedition with the final approach to Fort Garry and testified to the “order and tranquility which had rapidly succeeded to the period of disorder and passion.”

In part three, Ranoe specified the “natural advantages” that Manitoba boasted “for the purposes of settlement,” enumerated the alternative routes for getting to the province, and offered “many shrewd and practical suggestions to those who might contemplate making it their future home,” including “high tribute to the comforts of married life.”

Ranoe concluded “The Great North-West” with a call for justice. The Globe, said Ranoe, “demanded justice be done to the Indian, and that in the future there may be no cause for reproach of conscience, and that when what is now a prairie and a wilderness, becomes the garden and the wheat field, the flowers will bloom over no grave of oppression, nor hamlet be built upon land wrenched from the Indian but the Dominion will grow, based on justice, and truth and prosperity will flourish over the land.” This “generous appeal on behalf of the Indian tribes, for whom no settlement had yet been made,” was met with “continued applause.”

Harman retook the stage at this point and said he could “only interpret the continued and hearty applause as a vote of thanks to the fair and talented lecturer,” which inspired another ovation. The former Toronto mayor concluded the evening by offering Ranoe “the thanks of the audience.”

Ranoe delivered “The Great North-West” in Hamilton and St. Catharines in the following weeks, and the Globe and Telegraph said she planned additional readings, as well.

In March 1893, the sad news of the “accidental death of Mrs. Molyneux St. John, a lady well known and highly esteemed by the older residents of Winnipeg,” reached Canadians across the country. The Victoria Home Journal wrote: “survivors of an older generation” would remember Mrs. St. John “as Miss Kate Ranoe.”42 Ranoe was killed while crossing St. Catherine Street in downtown Montreal. An eyewitness said she was “leaning on her husband’s arm” when a runaway horse “with nothing on it except a few bits of harness” caromed down Peel Street and knocked her down. The witness said Ranoe was kicked “on the breast, which must have killed her instantly, for when picked up she was dead.”43 Ranoe was 49. The Globe said that “an immense number of prominent citizens” attended her funeral in Montreal, and her husband “received many messages of condolence.”44

Kate Ranoe, Montreal, 1868.

Molyneux St. John.

Six months later, Molyneux St. John moved to Winnipeg to assume duties as editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, a position he held until July 1895. The Winnipeg Daily Tribune said that St. John “proved himself to be a gentleman of sterling and most amiable character. In conducting the paper, personalities were most rigidly eschewed, and while many may have differed from the strongly partisan tone of the paper from a political standpoint, all must have respected its cleanness and desire to be fair.”45 It wasn’t long until St. John was on the move again, though, this time to work for the Department of the Interior in Ottawa. Seven years later, in January 1902, Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier appointed him Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod.

On January 30, 1904, St. John died of uremic poisoning. An obituary in the Globe tells of the painful, protracted ordeal:

A fortnight ago Mr. St. John was attacked with grippe, which induced a return of kidney trouble, from which he had been a sufferer. He was removed to St. Luke’s Hospital, where it was thought that with skillful nursing and good medical care he might recover. He grew gradually worse, however, and on Friday evening his physician called in for consultation with two specialists. At this consultation, Mr. St. John’s recovery was pronounced hopeless. The patient then continued to sink rapidly, and passed away in a state of unconsciousness.46

Molyneux St. John, “one of the best-known newspapermen in Canada,”47 was 67. He was buried next to the love of his life in Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery.

Remains of Colonel Wolseley’s transports, 1870.