RANDALL IS A 16-YEAR-OLD WITH A SIGNIFICANT HISTORY of physical abuse and neglect from his family of origin. He was introduced to TSY as part of his weekly therapy session in the residential treatment program where he had been living for the past year. Randall and his therapist had cocreated a 10-minute TSY program that they would do together, usually at the beginning of a clinical session. After a period of trial and error that lasted about 2 months, Randall had discovered a set of chair-based yoga forms that he wanted to use as a regular routine. For Randall, TSY had a lot to do with the physical shapes of the forms and he noticed that some body positions caused him too much pain—both physical discomfort but also psychological and emotional discomfort. Aware of the fact that TSY is focused on the visceral experience and not on translating body experiences into psychological or emotional content, Randall’s therapist worked mostly with helping him notice how his body felt in different forms and then, if he was uncomfortable in any way, practicing either modifying the form so that it was more physically comfortable or coming out of the form entirely. On this occasion, they were doing a gentle backbend together in their chairs that involved lifting the chin toward the ceiling and rolling back the shoulders (see Figure 3.1 for a picture of this form).

Randall had previously experienced this form as one of his favorites. He had enjoyed the feeling of lifting his chin and feeling the muscles in the front of his neck stretch. On this particular occasion, as they were doing the form together, the therapist invited Randall, as he often did, to notice what he was feeling in his body by saying, “You may notice some feeling in the muscles or the space around the front of your neck.” On this day, as soon as the words were uttered, Randall began to panic. “Ow!” he said. “The front of my neck really hurts.” This hadn’t happened to him before and it was new and unexpected. The therapist was also a bit surprised but before he could even respond to Randall’s distress, Randall himself actually verbalized, “I am going to come out of this form.” Fantastic! He had apparently internalized the process of choosing to come out of a form that was distressing and he could access this choice without the therapist cueing it. Normally, the therapist would have had to talk Randall through the choice process so this was also a new experience for the therapist. Randall proceeded to come out of the form but he didn’t stop there. Next he said, “I know what I can do,” and he folded forward with his forearms on the top of his legs, rounded his back slightly, and tucked his chin a little bit (see the form called Forward Fold, Version 1, in Chapter 8 for an example). This was another form that they had practiced together for several months. The therapist was just trying to follow Randall’s lead now so he too came out of the form and gently folded forward. “How does your neck feel in this form?” the therapist asked. “Much better,” Randall said, taking a deep breath. “I felt like a sharp pain in my throat in the other one but when I lean forward it totally goes away.” Randall was noticeably relieved. He had internalized the capacity to make choices about what to do with his body and he noticed that not only could he stop doing something that was painful but he could also move himself into another form that felt better.

Choice in TSY

What does it mean to make a choice? How is it that we choose one thing over another? The answers to these questions depend largely on who you ask. A neuroscientist may have one answer, a psychologist another, a philosopher yet another, and so on. In other words, each of these professional disciplines would emphasize a certain mechanism for choice making based on the area of expertise or professional bias (the function of neurons in the brain, past experience and learning, rational or irrational thinking, etc.). Readers will surely discern my own biases regarding choice making after reading this chapter. In fact, I will attempt to make some of them as clear as possible throughout the course of the book.

Along with bias, another important factor to consider regarding how we approach the process of making choices is the context, that is, are we choosing a new career path or are we choosing how high to lift our arms in a yoga form? The former is a choice that, to a large degree, involves our ideas so is therefore more cognitive (What job will best serve my financial needs? Where do I see myself professionally in 5 years? What job will make me happiest after I take it?), and the latter is a choice that mostly involves our experience of how our body feels right now so it is therefore less cognitive and more visceral. As we consider the practice of making choices with regards to TSY, it is useful to distinguish between choices that are more weighted toward reasoning and those related more to immediate, somatic experience. Additionally, these two examples—deciding on a job versus deciding how high to lift your arms in a yoga form—also illuminate another component of the choices we make, namely a temporal one. If we are thinking about a career path, we would probably be more concerned with the future (What choice will lead to my long-term happiness?) whereas how high to lift our arms in a yoga form invites more of a focus on the present (What do I want to do with my body right now?). When considering choice making and TSY, the context is our immediate body experience and the time frame is the present moment. In other words, all of the choices that we practice making in TSY are related to what to do with our body right now.

Figure 3.1. Gentle backbend: Lifting your chin and rolling your shoulders back.

Trauma as an extreme lack of choice

Additionally, our approach to choice making in TSY has evolved from our understanding that the kind of trauma our clients have experienced involves what can be referred to as an extreme lack of choice. For example, an infant born into a violent or neglectful home has no choice about those circumstances; this infant is trapped in every sense of the word. An infant born into this kind of chaotic environment would be incapable of making a conscious choice to leave such an environment (or to change it) so the lack of choice I am pointing to is even more complex and insidious than we might think at first. Consider this infant as an organism who, at this developmental stage, has mostly biological needs: nutrition, sleep, hygiene, but also, according to work related to attachment theory as we saw in Chapter 1, physical contact and the attunement of an adult caregiver. When an infant does not receive this care, attention, and affection, he or she fails to develop successfully (Ainsworth, 1979; Feldman, Eidelmann, Sirota, & Weller, 2002) and is at great risk for suffering from the effects of complex trauma years later (Anda et al., 2009). The infant is, in many ways, trapped and helpless. Perhaps we can agree that no organism would choose these conditions. No organism would subject itself willingly to an environment where it would fail to thrive and put its long-term health at risk (Corso, Edwards, Fang, & Mercy, 2008). Under these conditions it is as if the biological organism were making a desperate plea for mercy through its failure to develop in a healthy way, a plea that goes eternally unheeded because it cannot be uttered to anyone ever (there is no language) and the people most capable of understanding this language-less utterance and saving the defenseless infant are the ones who are causing all of the pain and suffering in the first place. Therefore, because the infant, the organism, is subjected to this kind of traumatizing environment without the ability to change it we can understand it as an extreme lack of choice and it is under these conditions that complex trauma flourishes. With TSY we counter this experience of extreme lack of choice with as many opportunities as possible for our clients to practice making real choices about what to do with their bodies.

Is it adaptation or choice?

Complex trauma has been described as a “cascading interplay between trauma exposure, impact and (mal)adaptation” (Spinazzola, et al., 2013, p. 8). As discussed in Chapter 1, trauma does not end with the event itself or the events themselves. Rather, particularly with complex trauma, the event is just the beginning because it will reverberate throughout our lives (the impact) and we do our best to adapt (or maladapt as it were). For example, research has shown that people who experience childhood trauma are at increased risk for dangerous behaviors such as drug taking (Dube, et al., 2003; Khoury, et al., 2010) and self-harm (Yates, 2004). While these dangerous behaviors can be understood as adaptations to the early traumatic experience, it is also true that society often has another interpretation that it operates from, which is important for us to consider. I contend that society in general most often looks on these adaptations to trauma as more of a product of free will. To an outside, uninformed observer, it appears as if we choose to take drugs, to cut ourselves, to engage in dangerous sexual relationships, and so on, as if we see a wide array of options for ourselves and are willfully picking. This isn’t the most honest way to understand what’s happening. It is my position that our traumatic experiences, being aberrations themselves, perform an insidious sleight of hand and effectively replace our free choices with adaptive responses. To the external observer there is no difference but to those who understand trauma the difference is everything and is in many ways the crux of the whole problem. If we are stuck constantly adapting to trauma, and the systems around us (society) are treating us like people making free choices from a completely open slate of options, then we have the recipe for pathologizing the traumatized person instead of the trauma itself. I realize this line of argument is veering in a political direction so I will stop here but the central point is very important for the development of TSY, namely that we want to differentiate between adaptive responses and making real choices, and we want to practice the latter.

Finally, even if, in the end, we still believe that traumatized people are making choices instead of adapting to trauma I would still argue that their choices become distorted and very limited by trauma, and we can use TSY to introduce a new and safer array of choices to people.

How to use TSY to bring real choices into therapy

There are three specific things we can do with TSY that will bring real choices into therapy:

1. Make everything an invitation instead of a command.

2. Connect choices explicitly to what can be done with the body right now.

3. Connect choices to interoception.

Invitatory language: The language of empowerment

I mentioned the use of invitations earlier in the book but now I want to shine a light on it. How we use language with these yoga exercises makes a huge difference in how therapeutic they are in the context of trauma treatment. As a reminder, Judith Herman says, “No intervention that takes power away from the survivor can possibly foster her recovery, no matter how much it appears to be in her immediate best interest (Herman, 1992, p. 133)..” The flip side of this argument is that the things we do that empower our clients foster their recovery. In the context of TSY, making every cue an invitation rather than a command is empowering. Invitations are empowering because they give people an opportunity to orient their frame of reference to their own internal experience as opposed to commands, which orient people to something external, namely the will and desire of the person in power. Consider these two statements:

1. Lift your right arm.

2. If you like, lift your right arm.

Notice what each of these statements feels like. Perhaps say them out loud to yourself. Please ask yourself the following when you consider each statement: Who is in charge? What if I don’t want to lift my right arm? What kind of relational dynamics does this statement foster? The first example is a command and with a command, only one person is in charge and it is the person giving the command. Not only that, but commands foster an externalization of experience because those who receive commands are always oriented to the person in power. And, yes, commands delineate a clear power dynamic. With a command it is implied that you really don’t have a choice, and we have already identified trauma itself as an extreme lack of choice. Commands reinforce the extreme lack of choice that accompanied trauma in the first place.

The second example, “if you like, lift your right arm,” is an invitation and it totally shifts the locus of control from the external to the internal. The addition of the simple phrase “if you like” presents the possibility for a genuine choice to be made by the invitee. Now, each person gets to make a choice for himself or herself. There is no external authority to either please or thwart. Perhaps more subtly, invitations also remove a moralistic component from the equation because what we do becomes a choice that is relativistic whereas a command implies right and wrong: in the sense that what the commander wants you to do is “right” and anything else is “wrong.” Notice how insidious this is—with a command like “lift your right arm” the rightthing to do is to follow the order of the external authority. To not lift your right arm is to do the wrong thing as well as to displease the person in power. If you have a real choice then you get to refer to your own experience and what is right becomes what is right for you, not for someone else. You get to practice making a choice unabated and uninfluenced by the will of some external authority. Complex trauma is about your will being constantly subjected to an external authority. You do not get to refer to your own expertise when you are traumatized (expertise, in this case, being the answer to the question of what do I want?). In fact, if you are repeatedly abused or neglected it is probably better to cut yourself off from your own expertise because you don’t get to use it anyway and you might as well save your energy for something more important, like survival. But what happens if we learn to live entirely disconnected from our own expertise, our own sense of what it is that we want?

With TSY we are interested in helping people refer to their own internal authority, particularly regarding what to do with their bodies, and a key way we do this is by using language to offer real invitations. We refer to this kind of language (like statement 2 above) as invitatory language. Our goal, and the encouragement for any clinician interested in bringing TSY into treatment, is that every cue be preceded by an invitatory phrase. Everything in TSY is an invitation and not a command and the more we can be committed to this premise the more effective the intervention will be in terms of trauma treatment. Other examples of invitatory language are “when you are ready,” “you may wish to,” “perhaps” (as in “perhaps, folding forward”), and “maybe” (as in “maybe taking two or three breaths in this form”). Please feel free to either use these phrases or to come up with your own that you are comfortable using as often as possible.

Choice making as an immediate body experience

In TSY, every choice that we make is related to something that we do with our body right in the immediate moment; we are not reflecting on past choices or anticipating future decisions. We are interested only in the choices we make right now in relation to whatever yoga form we are currently engaged in. The fact that our choices are body-oriented presents a particular challenge when working with traumatized people, and this needs to be explicitly addressed and reckoned with: for most of our clients, making choices about what to do with their bodies will be very difficult due to the very nature of complex trauma itself. Most of our clients hate their bodies and/or feel extremely detached from them. We have seen some of the clinical sequelae that are probably related to this hatred or disconnection, such as changes in the brain that make it difficult to sense or to interpret body experience. We can also imagine that an abuser is demonstrating so much hate and violence toward the body of a victim that if someone is steeped in this kind of environment he or she will eventually internalize that hatred. We are after all social animals, exquisitely attuned to the lessons we learn from each other (not to mention some of the more recent research into epigenetics that seems to suggest we may inherit genes that are also, in effect, attuned to and manipulated by traumatic experiences).

Because of this a priori challenge, the general encouragement when introducing body-based choice is to start with a simple framework that we can call an “A-B choice.” For example, if you would like to try an A-B choice, you are welcome to experiment with another neck exercise called head circles. With the head circles you are welcome to either do A (a half head circle) or B (a full head circle). Option A would be dropping your chin gently forward and then rolling your head from side to side. It’s like the bottom half of a circle. Option B would be to make a full head circle. Feel free to pause and experiment with these movements for a moment. As you can see, these options can be presented as an A-B choice with no other objective other than choosing between A and B. For some of our clients, experimenting with these A-B choices may be enough; this alone may add a new dimension to choice making and to trauma treatment. Your client may be clearly aware of the choice she is making or she may just pick A or B seemingly at random; it doesn’t matter. The encouragement is to keep offering these A-B choices as often as possible so your client gets to have the experience of making a choice in the context of her body.

Some of your clients may be interested in other aspects of choice making, in which case you can add some complexity. For example, from the head circle exercise initiated above, the next step might involve adding more choices, as in an A-B-C model: you can do A (a half circle), B (a full circle), or C (a U-shape or horseshoe-shape movement, like a three-quarter circle). Now you have added a third option and therefore more complexity into the mix. Now your client has an opportunity to broaden her choice-making spectrum and all of it is connected to what she is doing with her body. Every yoga form presented in this book provides opportunities to practice by making various A-B and A-B-C choices.

PRACTICE TIP: While it is possible to add even more choices to a yoga form, be careful of getting bogged down in one form for too long. If your client is starting to make it more of a cognitive exercise rather than a visceral/somatic one, take that as a signal that it is probably a good time to move on.

Connecting choices to interoception

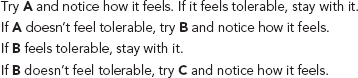

Another possibility, if your client is tolerating the A-B or the A-B-C choices and seems interested in even more complex choice making, is to invite him to start to notice what he is feeling in his body and to possibly connect what he is feeling to the choices he is making. For example, given our neck role exercise, the facilitator could say, “If you like, notice what the different options feel like around your neck and maybe let that help you make your choice.” This kind of invitation invites interoception into the process. Now your client has an opportunity to make a choice based on what he feels in his body. The choice process becomes anything but arbitrary. Now it is what do I feel and what do I want to do with my body based on what I feel? Figure 3.2 outlines how someone might use an A-B-C choice model combined with interoception.

Figure 3.2. Connecting an A-B-C choice with interoception.

When we start to get into an interoceptive practice like this, we, as facilitators, have to be really careful to let our clients determine what does and does not feel tolerable. In fact, I use the word tolerable just to illustrate the point but the recommendation in practice is to just invite your client to “notice what this variation feels like” and to remind him or her that “there are also other options for this form.” In other words, avoid using adjectives and adverbs like “tolerable” (or “good” or “bad,” etc.) when you are actually facilitating TSY and just let your clients have their own experience. They may tell you, “This form is uncomfortable,” in which case you can offer variations and invite them to notice how the variations feel. A very common experience is that a client will tell you that a form is uncomfortable but will not ask you for help. I usually experience this scenario as an effect of complex trauma where my client is used to being uncomfortable in his body and truly doesn’t believe there is any other possibility available or he doesn’t trust me (the authority figure) to be able or willing to help him relieve his pain. When this happens I still try to let him know there is another variation or two available for the form and I will demonstrate it myself and also remind him that he can always come out of any form for any reason. I try to meet that impact of trauma that my client is experiencing with something new: choices that can be made, which I support but do not command. Readers may be reminded of an earlier discussion from Chapter 2, where I made it a priority to not adopt a prescriptive stance toward your client where you are telling him or her what to do or feel. When you present choices like this, even though you are giving clients some possibilities, the process is still entirely nonprescriptive because you are inviting clients to notice what they feel and to be led exclusively by that experience.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Please remember that even though I present choices in a way where complexity can build, any of these choice-making practices will contribute to the work of trauma healing. The role of the facilitator is not to prescribe one choice model over the other but to be led by what is tolerable or helpful for each client at a particular time. In that way you maintain the integrity of the entire process, which is for the client to learn through practice to be guided by his or her own internal experience rather than by any external influence.

What not to do: How physical touch foils the power of choice in TSY

Because so many yoga classes involve physical assists (that is, yoga teachers putting their hands on their students and physically manipulating their bodies) I want to make this clear statement: in TSY, there are no physical assists. The facilitator will never place his or her hands on a client in the context of TSY.

I would like to share two pieces of supportive evidence in this regard. The first one is anecdotal. In the early years of the yoga program at the Trauma Center, we did do physical assists. We thought it would be a good idea for trauma survivors to be able to experience “safe touch” and we didn’t want people to feel “untouchable.” We thought we were doing the right thing. However, we started to get some troubling feedback. Several students, both long-term folks and newcomers, told us that when we said words like “if you like” and “when you are ready,” they took those words seriously. When we said, “You have a choice about how you do this form; there are options,” they trusted us. They told us that as soon as we put our hands on them (even in a very gentle way) all of these nice words went out the window. The experience was “I’m doing something wrong,” “the teacher is angry at me,” “I need to do it your way even though my body is trying to tell me something else,” or “I am now scared of you because you want me to do something with my body that I don’t understand or that I don’t want to do.”

As soon as we heard a few of these comments, we knew we had to drop physical assists entirely when working with victims of complex trauma. What appeared to be happening was that a physical touch was sending a different message than our words, no matter how well intentioned we were. In the context of TSY, people interpreted touch as threatening and dangerous, which, looking back, is completely understandable, given what we now know and have discussed in Chapter 1 about the impact of complex trauma (incidentally, when we first started the yoga program at the Trauma Center, there was no book like this to refer to so I am hoping to save you and your clients from some of the mistakes we made along the way). We were not honoring choices and invitations. TSY is supposed to be a place where you are totally, completely, unequivocally in charge of what you do with and feel within your body and when we as the facilitator put our hands on people we were sending the message that what our students were doing or feeling was somehow wrong.

We as a team quickly came to believe that this experience was sabotaging the entire process and was (at best) causing our clients to not trust us and to either stop attending sessions or dissociate more or (at worst) retraumatizing people. Imagine how painful it is for a trauma survivor to hear you say “you have choices” and then to experience you physically manipulating his body just as he is making the first tentative (and profoundly inspiring) steps to feel and make choices about what to do with his body. Our clients are people who have survived deeply abusive and neglectful relationships and the fact that external stimuli (our touch) are being interpreted as threatening is exactly the result that one would expect (Blaustein & Kinniburgh, 2010), regardless of the “good” intentions behind them. So we changed our methodology and eliminated physical touch.

The next important piece of information that came along later, which supported our no-touch approach, arose from the qualitative interviews done as part of our National Institutes of Health (NIH) study. It is very common for adult clients to tell us that being touched by their children or intimate partners is one of the worst experiences in their lives exactly because they expect it to be enjoyable; they want to enjoy hugging and cuddling their loved ones but they can’t. Many of the women in our study told us that after 10 weeks of TSY (that involved no touch) they were in fact able to be touched by their children and partners whereas before TSY that touch had been unbearable (West, 2011). This is critical information. Our speculation is that by practicing real choice in an invitation-based context where you are totally in charge of your body, what you do with it, how you move it, when you move it, you begin to learn to feel safe in your own skin. Once you feel safe in your own skin, you can accept the contact of others’ skin (your baby, your lover) and maybe even enjoy it. When the yoga teacher touches you in this context it sends messages of danger that override the work of choice, invitation, and interoception that actually need to be done in order for people to be able to enjoy being touched by appropriate people in their lives.

Conclusions

In TSY, choices are something that we practice intentionally in the present moment and that are not related to thoughts about the past or the future. Choices are always connected to forms—what we are doing with our body—though they may or may not be connected to interoception. We use yoga forms as opportunities to have different physical experiences where one can make a variety of choices about what to do with the body. Our work is to do our best to create an environment where our clients are empowered to practice choice without external coercion or influence of any kind.

Now that we have established the primacy of choice in the TSY framework, we can turn our attention to the next critical practice: action.