THIS CHAPTER OPENS WITH THREE DIFFERENT CASE vignettes that illustrate different aspects of rhythm as applied in trauma-sensitive yoga (TSY).

Reclaiming movement: A case story

“The first time we tried this I felt like I was being attacked again. Do you remember?” Vital said, while she and her therapist experimented with lifting up and holding their legs.

“As soon as I felt my leg muscles, it was like they were coming up behind me right then.” Vital had survived captivity, repeated rape, and torture in the Central African Republic, and she had eventually become a refugee in Europe where she met her therapist, Maria. Vital and Maria had worked together for about 2 years. The Leg Lift was done from a seated posture in a chair (see the Leg Lift exercises in Chapter 8 for examples), and they had started doing this form together, among others, very soon after they met. The first time they tried the Leg Lift together, Maria had simply introduced it as another form they could try. After a few seconds of lifting and extending her leg, Vital became very upset and tearful and she eventually shut down. They stopped the TSY session immediately and moved into a talk-oriented process but Vital was still deeply shaken, even at the end of the session. They made a plan to check in by phone the next day and to meet again in 3 days. Vital couldn’t even find the words to explain her experience to Maria until the next time they met in person. When she was able to talk about it, Vital said that as soon as she lifted her leg off the floor she literally felt like her attackers (several of whom she had known very personally since childhood, having attended school together side by side for years) were right behind her in Maria’s office about to attack. Vital was a physically strong and fit person, and she told Maria how, before all of the horrible things happened to her, she used to love to run and, particularly, to feel the strength in her leg muscles. For Vital, running was a way for her to, as she said, “connect with the body” and “feel alive,” and it felt as if this had been taken from her. She told Maria that she hadn’t been able to run since coming to Europe because, she now realized, she couldn’t stand to feel her leg muscles engage: “when I’d feel my leg muscles activate, for some reason, I didn’t feel safe.” Doing the Leg Lift brought all of this more immediately to her consciousness for the first time and she realized how much she missed being able to run. Vital now experienced this as a profound loss and she became interested in, as she said, “reclaiming” her legs. Vital told Maria, “I want to feel comfortable running again.”

As they talked this over together, they decided to keep experimenting with the Leg Lift but to modify it so that Vital could be in control of the experience. They decided to make it a movement rather than a static hold because Vital noticed, after they tried both options a couple of times, that she felt more comfortable with the movement. They started off by trying three of these leg lift movements with each leg; both Vital and Maria moved at their own pace. Vital noticed that it was critically important that she be in charge of moving her leg at her own pace but that it was also important that Maria was willing to do the leg lifts but not try to control Vital’s pace. In other words, what made this work for Vital was that both she and Maria were doing the leg lifts together but that each was responsible for her own pace.

After a few weeks they tried five movements like this with each leg. Within a couple of months they were doing ten leg lifts (Vital decided this would be the maximum) and it was at this point that Vital began to jog again.

Things begin and end: A case story

Juan spent a large portion of his time in therapy talking about how much he hated his body and how he literally fantasized about not having a body. On a hunch, Juan’s therapist told him about TSY and they decided to try a few forms together. One of the forms they tried together was a seated Forward Fold (see Chaper 8 for some variations). Upon trying the form for the first time, Juan realized a conflict playing out within his body in relation to the form: on the one hand he noticed that he actually liked the feeling of the stretch in his back muscles when he folded forward (again, this was unusual and unexpected for Juan because he couldn’t remember liking a body feeling before) but at the same time he became terrified every time he would incline forward even a little bit. Juan knew he was terrified because he realized he couldn’t breathe, though he didn’t have any direct feelings that he would be able to identify as fear and he did not experience any clear memories associated with folding forward. He just noticed he could barely breathe and this really scared him.

With regards to TSY, Juan’s therapist focused on two things: the fact that Juan could feel a stretch in his back and that he wanted to have access to this feeling in his body (he liked it) and the issue of breath (for more on breath, see Chapter 6). She did not attempt to investigate any trauma content with Juan related to folding forward and/or not being able to breathe nor did she ask Juan to attempt to make meaning out of his experience. In order to give Juan an opportunity to experience the feeling of muscles stretching in his back (Juan’s therapist recognized how rare it was for Juan to have a body feeling that he actually liked), she introduced a practice called the countdown. The countdown is when the TSY facilitator counts down from a given number to zero while a form is held (as always, the student or client can change a form or come out of it at any moment for any reason). The countdown gives an opportunity to experiment with a form for a short, very clearly delineated period of time. The key idea with regards to using the countdown is that everyone knows an end is always in sight and that the current experience will not last forever. After trying several different amounts of time together (a count of two, a count of five, and a count of three), Juan noticed that a count of three was just enough. He could feel his back but he could still breathe (the two count wasn’t quite enough for him to feel his back and the five count was too much and he noticed he started to have a hard time breathing). After a few weeks of folding forward for a count of three, Juan noticed that he could breathe fine, knowing there was an end in sight, and also that he could enjoy the feeling of muscles stretching in his back.

Connection with others: A case story

For Joann, the yoga class was her only social activity. She was the head of a research team at a lab and had many public responsibilities but she considered her “work self” very different from her “other self,” the person who had experienced physical and emotional abuse at home as a child and then subsequently within several intimate relationships over the course of her adult life. The yoga class, along with being her only social activity, was also the only thing she did with other people who, she knew, had also experienced trauma, though they never really talked about it. Her favorite part of the class was the Sun Breaths. This was when they would breathe and move together. The instructor would invite students to either match her pace or to go at their own pace. Sometimes Joann would intentionally match the instructor and other times she would experiment with her own rhythm. While she really appreciated having the options, there was one time when she noticed that everyone, including herself, was going at the same pace and she experienced a feeling of safety and connection to the people around her that she had never felt before.

Three different aspects of rhythm

Three different aspects of rhythm apply to the practice of TSY, which we will explore in this chapter: (1) immobilization versus movement, (2) passage of time, and (3) isolation versus connection with others. In our examples above we can see all three at work in different ways. Let’s take a look at each aspect of rhythm in some more detail.

Immobilization versus movement

Let’s begin with a clinical term that is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): avoidance. This is a behavioral symptom that must be present in order for someone to be diagnosed with PTSD and it involves a person staying away from people or places that remind them, either explicitly or implicitly, of their traumatic experiences. In the case of avoidance, what is most pertinent is that our body experience of the phenomenon involves things we cannot do, movements we cannot make, places we cannot go. It is this restriction on what we can and cannot do with our bodies as a result of trauma that opens the door for using rhythm as part of trauma treatment.

Judith Herman used the term “constriction” as a nuanced variation of avoidance, which she described as “avoiding any situation reminiscent of the past trauma, or any initiative that might involve future planning and risk” (1992, p. 47). The key word here is “initiative.” This is an action word that implies doing something with your body, and Herman suggests that her iteration of complex PTSD involves avoiding some instances of initiative as a direct impact of trauma exposure. Similarly, Bessel van der Kolk observes that one way to conceptualize trauma is as a failure of the organism to mount a successful defense against a threat, which then becomes a “conditioned behavioral response” that he calls “immobilization” (van der Kolk, 2006, p. 7). Again, the language here is very purposeful and not incidental; the overarching experience of a person who is traumatized is a physical one of chronic constriction and immobilization; it is experienced in the body, not in the mind. Avoidance, constriction, and immobilization are the antithesis of movement, the antithesis of rhythm. Constriction and immobilization short-circuit the natural movement inherent in the organism and calcify our physical experience into more or less one rigid thing, which is to use the body to avoid traumatic memory.

If we accept this characterization then we have to think about how we can address it. How do we treat an inability to move? (And, again, I am not pathologizing this experience but rather suggesting it is an understandable consequence of complex trauma; who among us would willingly expose ourselves to hellishly painful abuse and neglect or any situations that remind us of these experiences?) How do we become unconstricted and mobilized in the face of very real traumatic experiences that are constantly playing out within our bodies? By this point in the book it will come as no surprise to readers that the answer to these questions involves one more step beyond thinking or talking about it, which has been the traditional role of psychotherapy; it is about moving our bodies right now (as we shall see, sometimes in a very purposeful and self-directed way, at other times just for the sake of movement).

Consider the example of Vital above. There was a moment in the process when Vital verbalized her experience with the Leg Lift and then she and her therapist talked together about how they might approach her desire to reclaim her leg muscles. So while talking did play an important part in this case in terms of helping them plan what to do, the treatment actually centered on moving the body, on doing the Leg Lift together, and on Vital being able to control the pace of the movement for herself. Again, some clients may find it very helpful to engage in more of an objective analysis of their experience but some may not and, especially given what we have learned from the neuroscience research, some may not be able to put into words what it feels like to be constricted or immobilized (see van der Kolk, 1994, for a reminder of the impact of trauma on parts of the brain related to speech).

While Vital found it useful and was able to draw a connection between her present experience of feeling overwhelmed by lifting her leg and her past experience of trauma, a more common scenario in our experience would be that someone feels terrified by lifting his leg but doesn’t know why. He just has a visceral reaction and that’s all there is to it. It may well be that by lifting his leg he has suddenly been exposed to an implicit reminder of trauma. He may have unconsciously been avoiding this action of lifting his leg because the motoric activity itself may contain traumatic memories. This highlights for us the importance within TSY of never forcing experiences on people, being attuned to when our client finds something like a leg lift intolerable in the moment, and knowing that we can always move out of a form and/or into another form. However, if the form is tolerable you can invite your client to notice it for what it is: in the case of the leg lift, activity in the leg muscles. In Vital’s case, she noticed she had been unable to move her legs in any way that caused her muscles to engage to a certain degree where they were feel-able. Moving her leg into the Leg Lift caused enough muscular activity for her to experience what is commonly referred to as a triggered reaction and she became very upset. The work between her and her therapist was to find a way for her to move her leg in a very controlled fashion, to thereby reclaim movement in her legs, and to eventually run again.

The key to using TSY to practice movement is to accept that physical movement alone, without the intellectual association with trauma, may be enough to allow people to have new, healing experiences (again, granted, some of your clients will also benefit greatly from being able to talk to you about their experiences, including associating particular movements with trauma).

Passage of time

Another important aspect of rhythm is time, namely the experience that things begin and end. While this is a topic that can quickly pull me outside of my area of expertise, I think there is some relevant clinical material that needs to be cited regarding trauma and time. Another way we can objectively judge an organism’s relationship to time, and particularly to the passage of time, is related to sleep patterns. A healthy organism operates with a highly attuned internal clock. The literature indicates that the parts of the brain most involved in our sleep and wakefulness patterns (as well as other important rhythmical patterns like eating and sex) are the thalamus and the hypothalamus (Saper, Scammell, & Lu, 2005). These brain regions are associated with the interoceptive pathways, which we know are compromised by trauma (see Chapters 1 and 2 for more about the interoceptive pathways). We also know from the research that traumatized people are more likely to experience sleep disturbances than their nontraumatized counterparts (Chapman et al., 2011). These findings point to a disturbance in fundamental circadian rhythms, our basic sense of time on an organism level, as a result of trauma.

Another aspect of time that seems to be impacted by trauma comes more from an anecdotal perspective based on what clients tell therapists (and occasionally yoga teachers), which is that bad things, even difficult things, don’t feel like they are going to end. In particular, I invite readers to consider the experience that has been discussed previously in this book that has direct bearing, which is that traumatized people are in a sense compelled to orbit around their trauma ad infinitum. That is, the trauma is so compelling on an interpersonal and neurobiological level that it never ends; it’s like having the same song stuck on replay. With TSY we want to give our clients the possibility to press “stop” and to play another song if they choose. Another way to formulate this phenomenon is that, for traumatized people, time stops moving; things stop beginning and ending.

Consider again the Vital example. It turned out that time had stopped moving for her in a very real way though she didn’t know it until she was invited to try the Leg Lift. She hadn’t realized that beginnings and endings had been replaced by trauma until she lifted her leg and contracted the large muscles on top of her thigh, and, instead of feeling her quadriceps contract, she felt like she was about to be attacked. This kind of experience is very common for clients at the Trauma Center. In a very real way, time had become calcified for Vital in her leg muscles. They were no longer her muscles that could move through time, contracting and extending and resting; they were where trauma was experienced by her as a constant presence in her body. While Vital was able to notice that her leg muscles had in effect been hijacked by trauma, most of our clients at the Trauma Center who have survived early childhood trauma cannot make that connection between an experience in their bodies and the abuse and neglect they endured as infants. That’s okay. In fact, TSY in no way requires this cognitive connection in order to be a successful treatment. The process would be to just work with each of your clients to find parts of the body that are feel-able for them and begin to experiment with noticing things happening, sensations changing, in those muscles based on the forms they are doing. If one body part causes too much distress, just move on to another body part. The purpose of this work is to be able to use your body to feel things begin (like a muscle contract) and to feel things end (when you make that muscle stop contracting). The work is not to expose people to parts of their body that cause them distress as a way to reframe their relationship with that particular body part. Any part of the body will do for this kind of TSY practice.

Further, as in the Juan example, the facilitator has a key tool available to help her clients reestablish a sense of beginning and ending: we call it the countdown. I use the countdown most often when someone is experimenting with holding a form that is challenging in some way. The challenge could be something physical like using a large muscle group or it could be something more psychological, as in Juan’s case. By counting down from five to one or from three to one, you can put an explicit marker on time: this thing we are doing together has begun and it will end when I get to one (of course, we can remind people they are welcome to come out of any form at any time for any reason). While they are in no way obligated to hold the form for your countdown, they have the option and they can rely on the “clock” you are keeping as a way to practice experiencing something intense in their bodies.

Finally, as part of this process, it may be important for the facilitator to give the invitation at the end of the countdown for the client to notice that whatever dynamic he had created in his body is now over and he may feel that change. Your client may try to distinguish a body feeling like a muscle contracting from displaced trauma; giving him a chance to notice what it feels like when that muscle stops contracting both puts an end to the period of time in which the contraction was occurring but it also gives him a chance to feel directly that challenging things do in fact end.

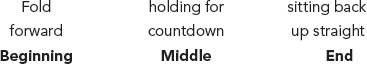

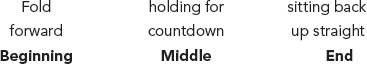

This brings up one final aspect of time: if we have a beginning and an end we also have a middle. The middle is when we are taking the action that was initiated at the beginning (in Juan’s case it started with him folding forward). The middle is also when the dynamic we created at the beginning is happening (in Juan’s case this was when his back muscles were lengthening) though, in TSY, we may or may not feel these dynamics. Figure 7.1 depicts Juan’s experience in relation to time.

Figure 7.1. Juan’s experience in relation to time.

Each yoga form has a beginning, middle, and end. For many clients it will be important for us to help them start to feel this aspect of time right in their bodies.

Isolation versus connection

Judith Herman has written that “helplessness and isolation are the core experiences of psychological trauma. Empowerment and reconnection are the core experiences of recovery” (1992, p. 197). While I have mentioned her formulation of empowerment as part of trauma treatment throughout this book, in this section I want to focus on isolation versus reconnection. This paradigm suggests that trauma has a tendency to isolate us from others whether it is very explicit, as in being kept captive by a perpetrator, or more implicit, as in feeling like no one understands the things you have been through. In either case, part of treatment involves finding a way back into the company of others. With TSY, we focus on a physical aspect of sharing space with other people, namely, doing things together. As I have noted previously, most clients at the Trauma Center have experienced interpersonal trauma, abuse, or neglect perpetrated by one person on another. Trauma treatment, whether it is individual psychotherapy of any type or a body-based praxis, is also fundamentally a relational thing, something that occurs between people (setting aside such experimental interventions as those being undertaken by the military to use videogame-type interfaces as part of an exposure treatment for combat soldiers with PTSD). If we are to offer good therapies we need to return again and again, in both our understanding and our therapeutic offering, to the relational dynamics of both trauma and treatment. The experience of moving together with another person is an explicit way that we can practice truly being together—sharing space. It is also another aspect of rhythm.

In the Joann example, we have a situation where the rhythmical practice of doing something together is in itself therapeutic. While trauma is something that people do together, it is not truly rhythmical; the power dynamic is so distorted and abusive that it becomes one person doing something to someone else. It is not a mutual process where both people have an equal capacity to affect the outcome. Trauma is when one person exerts all of the control and under these conditions a truly rhythmical interaction is not possible. In contrast, an interaction can be considered rhythmical if both parties enter into it through their own choice. A rhythmical interaction is one that is cocreated and where both (or all) parties have equal influence on the outcome. TSY seeks to give clients a chance to have rhythmical interactions as a way to practice reconnection. Because of the interoceptive, invitational, and choice-oriented approach to TSY, the facilitator does not have more power in the relationship than the client. Let’s not fool ourselves here: your client comes to you for help and she needs your expertise. I am not suggesting that you withhold or deny that. What I am suggesting is that, with TSY, sharing your expertise does not involve setting yourself up in a position of power over your client but rather involves you attending to your own interoceptive and choice-oriented investigation of the form at hand so that your client is free to do the same. The process becomes another aspect of the shared authentic experience that we previously discussed where both parties have equal power. The relationship, for that moment, is neither hierarchized (i.e., therapist/client or healthy person/unhealthy person, even not traumatized/traumatized) nor externalized where one person must conform to the other. Rather, everyone’s attention is internalized and focused on what he or she feels and notices and in this subjective domain there can be no external expert. When the therapist and client do these exercises together they engage in interacting with the same material at the same time and in the same space. There may be what looks like two people moving and breathing at the same time but fundamentally, beneath the surface, there are two people each relating to their own subjective and equally valid experiences and neither actor is imposing his or her experience on the other. I would suggest that when these conditions are met then you are doing trauma treatment in the best sense; you are having a truly rhythmical interaction.

Sun Breaths

Figure 7.2 and 7.3 offer an example of the movement exercise depicted in the Joann case that invites you and your client to connect on a visceral/somatic level.

These forms are presented as a sequence that involves coordinating movement and breath. Readers may wish to experiment with the Sun Breaths alone or with someone else. In either case, if you like, begin in a comfortable seated form. You may wish to bring your hands to the tops of your legs. As you breathe in, you may wish to experiment with lifting your hands a few inches up from your legs, as depicted in Figure 7.2. As you breathe out, you may wish to bring your hands back down to the tops of your legs. Figure 7.3 shows an option where, on the in breath, you lift your arms higher and this is also a possibility. Feel free to experiment a little bit with this breathing and moving pattern and with finding a gesture that is relatively comfortable for you. Once you get comfortable enough with the movement pattern, you may wish to find a pace that feels good to you. If you are doing this with someone else, it is okay if both participants go at a different pace. In any case, if you like, give yourself a minute or two to move and breathe at your own pace. The other option, if you are with another person (or more than one), as depicted in the Joann case, is that one of you can set a pace and you can invite the other to experiment with following your pace. The encouragement is to set a pace that feels authentic, comfortable, and natural to you, based on your own interoceptive experience with the form. Finally, you can trade off who sets the pace and who follows if you like.

Figure 7.2. Sun Breath Variation.

Figure 7.3. Sun Breath Variation.

Rhythmical attunement in TSY

In the clinical literature when attunement is discussed it is most often of the type described by Daniel Stern as “affect attunement.” When Stern writes, in the case of affect attunement, “what is being matched is not the other person’s behavior per se but rather, it seems, some aspect of an internal feeling state” (1985, p.142) he indicates that his conceptualization of attunement seems to focus on an emotional resonance of internal states—happy, sad, hopeful, and so on—that are first experienced by one person and then essentially mirrored by the other. In fact, a good portion of Stern’s excellent book The Interpersonal World of the Infant is devoted to wondering how one can most effectively attune one’s affect so that the other can really sense this connection. While Stern’s work focused mostly on the mother-infant dyad, the investigation of affect attunement has broadened to include other relationships and other life stages (Hrynchak & Fouts, 1998). Simply put, with affect attunement the emphasis is on emotional states.

With the kind of attunement we explore in TSY, the emphasis is on the body experience. What happens is that the facilitator and client both become involved in the practice of doing something together, each in charge of his or her own body but at the same time and in the same space. It may be that they have the same interoceptive experience but it is also very likely that they each feel something different. The act of doing something together is itself a kind of attunement that we can call rhythmical attunement. This rhythmical attunement then makes other kinds of experiences available, which are themselves other types of attunement, such as the shared processes of interocepting, choosing what to do, and taking action. Once this sort of relationship is established, then both you and your client are free to have your own experiences without imposing them on each other. In one instance your client may say she feels something or tells you she is making a choice to modify a form so that it feels better and you can simply reflect that back: “that’s amazing that you felt that” or “that’s fantastic that you made a choice to change that stretch so that it felt more comfortable.” In another instance one party may feel something and tell the other about it and the other party may then notice a similar feeling in his own body. I personally have had many experiences like this. On one occasion a student and I were experimenting with a seated twist and I focused on the feeling in the muscles around my rib cage. The student said, “I notice some feeling in my hip muscles” and as soon as she said that I also noticed a feeling in my hip muscles! I told her about this experience because it was genuine and it seemed interesting and I felt like that was an aspect of the kind of attunement that TSY makes available.

Finally, another way to consider attunement in this context is that when your client moves to adjust a form, you may follow him with your body or vice versa. Let’s imagine that you are practicing raising your arms to shoulder height and taking a few breaths and noticing how that feels. Your client may instead reach his arms up overhead and say, “My neck was getting sore and this feels a lot better.” Along with reflecting back how great that noticing and choice making was, you may also raise your arms higher as well. Now you are matching his body movement. You may need to ask “Is it ok with you if I try that as well?” because some people may feel uncomfortable with you matching them like this. Assuming it’s ok and you raise your arms, then you notice how that feels for you and possibly you can also feel some kind of dynamic shift around your neck muscles (maybe not and that’s ok too—be honest!) Now you are dancing together; you are moving together; you are practicing levels of attunement based on your body experiences.

Conclusions

Rhythm is an important part of good trauma treatment in general but is a core essential element of TSY. By being attuned to our rhythmical interactions we get to practice finding ways of moving and breathing that are authentically comfortable. By attending to aspects of rhythm we get to have experiences where one person does not impose his or her will on the other but rather, by being committed to the interoceptive process, actually validates the authenticity of the other’s felt experience. The countdown technique, an aspect of rhythm, gives us a way to practice noticing when things, particularly challenging things, begin and end.

For, ultimately, healing trauma is about learning viscerally something that is completely shrouded from awareness when one is in trauma’s thrall: things end. Once we know in our body that things end then the next part of our life can begin.