3

“Let Me Ride”

Gangsta Rap’s Drive into the Popular Mainstream

The real city, one might say, produces only criminals; the imaginary city produces the gangster.1

Robert Warshow

Straight outta Compton is a crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube From a gang called Niggaz Wit Attitudes.2

Ice Cube

Writing about the infamous genre of gangsta rap in the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising, Robin D. G. Kelley offered a political reading of rappers’ outlaw theatrics. By inflating their reputations for starting trouble and inflicting pain on those who dared to get in their way, he argued that rap artists cultivated “badass” identities that allowed them to stand up, symbolically at least, to the powers that be.3 Kelley explained that by inverting conventional morality and racial hierarchy through their irreverent and boastful signifying, gangsta rappers had carved out a space where they could critique the police brutality, racial profiling, and socioeconomic forces criminalizing black youth.4 However, reminding readers that rap is primarily “produced and purchased to drive to, rock to, chill to, drink to, and occasionally dance to,” Kelley also maintained that rap’s sociological implications should not prevent us from acknowledging the music’s aesthetic value, explaining that it would be a gross misunderstanding of rap music and hip hop culture to ignore the pleasure that listeners find in gangsta beats and rhymes.5

Kelley’s call to balance politics and aesthetics in writing about rap provides a useful starting-point for this chapter, which compares the way that lyrics, sound, and imagery work together in Los Angeles–based gangsta rap. Building on the previous chapter’s exploration of Public Enemy’s revolutionary black aesthetic, I compare producer Dr. Dre’s work with pioneering gangsta group N.W.A. (Niggaz Wit Attitudes) to hit singles from his later solo album, The Chronic, to explain how changes in sound lead to differing ideas about race and politics. Although gangsta rap is often discussed (and denounced) as a singular entity, the stylistic evolution of the subgenre, as well as the internal tensions within it, have been largely overlooked.6 Comparing two different iterations of so-called gangsta rap, this chapter focuses attention on the aesthetic features of individual songs, including the music that Kelley reminds us should not be forgotten.

Although Dr. Dre’s production for N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton, the influential 1988 album that brought West Coast rappers to the attention of national audiences, evoked the frenetic atmosphere of inner-city Los Angeles, the hit singles from his 1992 solo debut The Chronic seem more relaxed and fluid, a style that Dre called “G-funk.” Celebrating The Chronic as one of the most influential and popular rap albums in history, numerous critics and fans praise Dr. Dre’s meticulous approach to beat making. However, a vocal minority have long countered that Dr. Dre and his protégé Snoop Doggy Dog depoliticized gangsta rap, veering dangerously into exploitative misogyny and senseless violence. Rather than treat these contrasting opinions as separate issues (e.g., good music but bad lyrics), this chapter explores how Dr. Dre’s musical innovations as a producer were central to The Chronic’s sounding of black politics.

As Robert Warshow explains in the epigram to this chapter, the gangsta is a uniquely urban archetype, a product of the “imaginary city.” Hailing from Compton, California, an inner suburb known as the Hub City for its proximity to downtown Los Angeles, Dr. Dre and the other members of N.W.A. made place a central element in their musical strategy. In comparing the music of N.W.A. to Dr. Dre’s G-funk, I consider how musical aesthetics contribute to two different representations of identity, as well as two contrasting experiences of the city.7 By reconceiving the gangsta’s relationship to urban space, Dr. Dre rearticulated blackness not as conflict and rebellion but as transcendence and mobility.

RAPPING AND MAPPING

In recent years, scholars have become increasingly attuned to the spatial character of musical practices. Analyzing the dynamics of space and place at the heart of the genre’s growth and expansion, Murray Forman explains that rappers often cultivate an aura of authenticity tied to their respective ’hoods.8 Making Compton, California, a central part of their identity as a group, N.W.A. encoded experiences of black Los Angeles in their rap recordings. Writing for the Washington Post, music critic Richard Harrington picked up on such meanings when he described N.W.A.’s album Straight Outta Compton as a chronicle of “the crack- and crime-ridden black community of L.A.”9

Despite this tendency toward spatial thinking, however, it is important to emphasize that music derives much of its power from the way it structures temporal experience. To understand how music “maps” a particular space, one must also deal with the fact that music is experienced in time. As we have seen in previous chapters, rap producers create cyclic arrangements built on repeated passages of music (sampled or otherwise). These repeating musical loops, derived from the breaks that hip hop’s first DJs worked with, can vary considerably with respect to expressive character, breaking up time in different ways for vastly different effects. The challenge is to translate these temporal dimensions of rap music into a greater understanding of how gangsta rap portrays the urban space, highlighting the potential disjuncture between some people’s imagined ideas of a place and other people’s lived realities. Pace Chuck D of Public Enemy (who once famously referred to rap music as the “black CNN”), gangsta rap does not aspire to objectively reflect the city in a documentary manner.10 Rather, N.W.A. and Dr. Dre envisioned Compton (and the larger geography of Los Angeles) in particular ways for particular purposes at a particular time. If the metaphor most appropriate for understanding music’s spatial character is that of a map—an aural cartography—then we must acknowledge that different maps can lead to very different understandings of urban space. Maps are designed to reveal certain things, but they always conceal others in return.

As the founder of the “L.A. School” of postmodern geography, Edward Soja has brought increased attention to the forces that contribute to the fabrication of social space. Drawing on the theoretical insights of Henri Lefebvre, Soja refuses to see space as a neutral or blank grid against which social activity occurs. Instead, he interprets the city’s spatial dimensions against the forces of capital, creating opportunities and setting limitations on development and growth. Soja’s Postmodern Geographies contains a lengthy chapter on Los Angeles, and he dubbed the city the “paradigmatic place” to witness the effect of capital on the production of social space.11 Although Soja did not explicitly consider popular music, his analysis reveals many of the social and economic conditions that set the stage for 1980s gangsta rap. Published in 1989, the year in which Straight Outta Compton captured a national audience, Soja’s work provides a useful counterpoint to N.W.A.’s musical representation of urban space. In fact, his analysis of Los Angeles’s socioeconomic conditions opens a hermeneutic window for understanding N.W.A.’s aesthetic strategies.12

In the period stretching from World War II to the early 1960s, the area sprawling southward from downtown Los Angeles toward the port city of Long Beach was one of the largest urban industrial centers in the world. The heavily segregated area—African Americans were only allowed to inhabit a thin section west of Alameda Boulevard—became the third-largest black ghetto in the country. Despite the deleterious effects of segregation and systematic racism, blue-collar South Central Los Angeles presented opportunities for upward mobility, making the area an attractive destination for thousands of African Americans who moved to Southern California from Alabama, Texas, and other parts of the country.

By the 1960s, however, South Central Los Angeles was beginning its precipitous decline as factories began closing and laying off employees. Paradoxically, other regions of the metropolitan area were experiencing high levels of growth, leapfrogging south into Orange County and northwest into the outer San Fernando Valley. From 1970 to 1980, Los Angeles’s population grew by 1,300,000, and non-agricultural wage and salary workers increased by an even greater number—1,315,000—making Los Angeles the largest job machine in the country.13 Soja analyzes this differential growth and contraction in Los Angeles’s economy as a kaleidoscopic mix of highly educated and skilled labor at the top and a poorly paid immigrant workforce at the bottom.14 For example, while the high technology and military sectors were hectically booming thanks to the Reagan-era defense build-up, older industries such as rubber, steel, and auto manufacturing were losing their place in the global economic order. For Compton and South Central Los Angeles, this deindustrialization, which also meant the decline of labor unions and union wages, was coupled to the growth of an informal underground economy, led by a gang-controlled drug trade.

Los Angeles was both enabled by and particularly vulnerable to the mobility of capital.15 According to Soja, the city was prone to rapid demographic and economic change because it was not built around the centralized industrial districts characteristic of nineteenth-century modes of production. By the time Los Angeles began its industrialization, the more decentralized practices of early-twentieth-century capitalism were already well under way, enabled by one of Los Angeles’s defining symbols: the automobile. Indeed, the sprawling metropolis with its arterial network of freeways has been the most automobile-oriented region of the United States, excepting Detroit itself. The automobile industry boomed in Los Angeles throughout the Great Depression, and cars played a central role in Southern California’s postwar economic expansion.16 As residential suburbs and “satellite cities” continued to grow, the automobile shuttled commuters between their homes and places of work.

Although daily users often describe Los Angeles’s freeway system as a gridlocked prison, its origins lie in a dream of freedom. Its postwar boosters billed the construction of Los Angeles’s freeways as central to the suburban good life. Over the protests of the inner-city residents whose lives and neighborhoods were vulnerable to the destructive effects of freeway construction, proponents of the freeways presented the city as “the sum of its attractions,” emphasizing that Los Angeles’s freeway system would make it possible for the average middle-class car owner to take advantage of all the Southland had to offer.17 By viewing the city as a “collection of isolated sites, each severed from its sociohistorical context,” freeway developers tapped into a vision of decentralized Los Angeles that had long been enshrined in the city’s planning.18 Streetcars and rail lines, for example, had served the sprawling metropolis for decades before the rise of freeways. The new freeways were, in fact, a solution for suburban commuters dissatisfied with the high cost and poor efficiency of the rail system.19

Like the streetcars and rail lines before them, the freeways allowed commuters to traverse the long distance from home to office, and they enabled sightseers and middle-class families to enjoy a wide variety of activities spread across a wide expanse of land. Yet they also contributed to the isolation and invisibility of many poorer Los Angeles communities, including South Central Los Angeles. Thousands of people passed through the city’s black neighborhoods each day on their way to work, but the conditions in these areas were hidden behind the freeway’s walls. What is more, the freeways reinforced patterns of segregation and marked physical boundaries cutting African Americans off from other parts of the city. Figure 15 illustrates roughly the area of South Central Los Angeles and neighboring black communities (including Compton) circumscribed by Interstates 10, 110, and 710 and State Route 91. As houses were razed and large swaths of earth cut open to make way for these roads, communities were divided by cul-de-sac streets that dead-ended into towering sound walls. For those without easy access to automobiles, the freeways and inadequate public transit system make movement across Los Angeles’s vast expanse difficult. Many activists and community members have charged Los Angeles with supporting a “transit apartheid” in which the ability to move through urban space remains contingent upon class and color.20

N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton responded to the conditions of neglect and segregation plaguing Los Angeles’s black community, creating and disseminating a ghetto-based understanding of the city’s spatial dynamics. Scholars Robin Kelley and Eithne Quinn, for example, both interpret the very ethos of early gangsta rap, which celebrated the ruthless, individualistic pursuit of profit, as a cultural strategy for opting out of the low-skill, low-wage service economy that Soja describes in Postmodern Geographies.21 N.W.A. was inspired by the crime, violence, and chaotic atmosphere surrounding the underground drug trade, which had flourished in the void created by massive layoffs and high rates of unemployment. The rise of gangs that fought bitterly for control of the lucrative drug economy was met with a heavy-handed response from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). Despite being chemically identical to powder cocaine, which was associated with wealthy white users, the news media and law enforcement agencies exaggerated the dangerous effects of smoking “crack” cocaine. In this context of public panic over the crack cocaine “epidemic,” the U.S. Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which allowed crack possession to be punished at a rate one hundred times greater than that for powder cocaine and stipulated new mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines for drug crimes that previously would not have resulted in imprisonment.22 These measures disproportionately affected African Americans who lived in communities where street dealers made easy prey for law enforcement, and the LAPD response to the drug-and-gang problem was particularly aggressive. With names like “Operation Hammer,” the LAPD’s actions included roundups of suspected gang members and destructive search-and-seizure missions whose purposes were not only to find contraband but also to intimidate. The War on Drugs provided a pretext for the LAPD to adopt paramilitary equipment such as the “batter ram,” a small tank whose purpose was to break down the doors and walls of suspected crack houses in dramatic fashion.

Figure 15. Boundaries of South Los Angeles neighborhoods (c. 1986), reinforced by Interstates 10, 110, and 710 and State Route 91.

Exploiting the stereotypes and popular imagery of the ghetto as a violent and troubled “no-go” zone, gangsta rappers found a way to make infamy pay. By embodying outlaw personae through first-person gangsta narratives, N.W.A. developed a sophisticated cultural hustle that allowed them to profit from the very system conspiring to contain them. This artistic strategy had a powerful—and somewhat ironic—musical component. The sound of Straight Outta Compton, which supports N.W.A.’s grass-roots mapping of South Central Los Angeles as a place where black residents are economically and physically cut off from other parts of the city, depended on musical techniques imported from New York and transposed onto remarkably similar post-industrial conditions.

COMPTON VIA NEW YORK

Before the rise of West Coast gangsta rappers, New York City’s MCs were the uncontested trendsetters in rap music. Not only did the most famous rap artists hail from the city, but New York was also the center of production for managers, record labels, and recording studios. Although few might have thought of it in such terms at the time, the national sound of rap music in the early-to-mid-1980s was actually a regional one. Virtually everything in rap, including the music’s sound, slang, and sense of fashion, came from New York. MC Chip, an original member of N.W.A., recalls, “Early, early West Coast hip-hop, before it became gangsta, we were looking for an identity.”23

Evidence of the group’s search for an identity can be found on N.W.A. and the Posse (1987). Released by Macola Records (apparently without the group’s consent), the uneven and stylistically diverse album provides a snapshot of what Los Angeles–based rap music sounded like prior to N.W.A.’s breakthrough, Straight Outta Compton (1988). As manager Jerry Heller recalls, the album was “the product of a loose amalgamation of DJs, musicians and MCs,” and captured the group at a moment when the direction of their musical careers had not been fully set.24 Indeed, for those familiar with N.W.A.’s later albums, one of the greatest outliers on N.W.A and the Posse is “Panic Zone,” a song in the L.A.-based “electro rap” style.

One of many regional styles spawned by Afrika Bambaataa’s powerful 1982 hit single “Planet Rock,” electro dominated Los Angeles–based rap in the years before N.W.A.’s rise, roughly 1983–1988.25 Like their counterparts in cities across the country, electro groups began as mobile DJ units, displaying a flashy and ostentatious style associated with the nightclub scene. Dr. Dre, for example, began his music career with the World Class Wreckin’ Cru, which also included original N.W.A. member Arabian Prince. Dressed in bright sequined shirts and with a stethoscope draped around his neck, Dre used turntables (for scratching), electronic keyboard synthesizers, and drum machines to help craft electro’s futuristic-sounding world of fantasy and sexual innuendo. “Panic Zone,” a song whose minor-key riffs, percussive synthesizer stabs, and bleeping electronic drum track bear a strong resemblance to “Planet Rock,” reveals Dre’s and Arabian Prince’s lingering ties to the electro scene. However, unlike “Planet Rock,” which aimed itself rhetorically toward a global party audience, the lyrics to “Panic Zone” named specific places of origin for each respective member of the group: L.A., Compton, Inglewood, East L.A., West L.A., Carson, Crenshaw. Thus, the track reflects N.W.A.’s self-conscious concern with place, a strategy that would prove central to the group’s breakthrough.

N.W.A. founder Eazy-E, who also cofounded the group’s label, Ruthless Records, with Jerry Heller, was known to dismiss electro groups as “corny.”26 Like Run-D.M.C. and Public Enemy, discussed in the previous chapter, N.W.A. would build its identity in opposition to the flamboyant costuming and dance-floor orientation of its predecessors. Eazy-E’s first task was to convince Dr. Dre and the other members of the group to focus on a more hardcore style of rap. Their first single in this vein was “Boyz–N-the-Hood.” The single was written by Ice Cube but rapped by Eazy-E. Set to a sparse drum machine track with a tempo too slow for dancing, the song describes Los Angeles’s tough city streets as seen from Eazy-E’s 1964 Chevy Impala lowrider. The song’s mix of misogyny, violent imagery, and braggadocio was clearly indebted to Philadelphia rapper Schoolly D’s “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean?),” a 1985 single widely regarded as the song that gave birth to gangsta rap. It also drew on Ice-T’s “6 in the Mornin’” (1986), which was the first West Coast song to adopt the lyrical cadence, defiant attitude, and violent yet humorous boasting of “P.S.K.” “Boyz-N-the-Hood” was both thematically and musically similar to these predecessors and helped plot a new course for Los Angeles–based rap.

With the support of Los Angeles’s AM 1580 KDAY, the city’s first all-rap radio station, “Boyz-N-the-Hood” was a hit. While manager Jerry Heller signed the group to a national distribution deal with upstart Priority Records, N.W.A. continued work on their first album as well as Eazy-E’s solo project Eazy-Duz-It. According to Chuck D, Public Enemy’s musical style directly influenced Dre’s work on these albums, and he recalls giving the first two copies of It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back to Dr. Dre and Eazy-E prior to the album’s official release.27 The recorded evidence supports Chuck D’s recollection. For many of the tracks on Straight Outta Compton, Dr. Dre seems to have borrowed from the “loops on top of loops” style of Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad.28 N.W.A.’s breakthrough was finding a way to put a distinctive spin on these influences, and the artistic strategy that they arrived at for their first Ruthless Records release was designed to put them on the map—both literally and figuratively.29

Rather than shout out the multiplicity of neighborhoods where their members were actually from (as they had done in “Panic Zone”), N.W.A. chose to center their identity around Dr. Dre and Eazy-E’s hometown of Compton, California. The sound of Compton as Dr. Dre imagined it, however, drew on musical practices and artistic decisions similar to those found in Public Enemy’s “Rebel Without a Pause.” To construct the rhythmic foundation of “Straight Outta Compton,” Dre looped the breakbeat from the Winstons’ “Amen Brother” (1969) (ex. 3a).30 Like other heavily sampled breaks from this era, the one-measure loop features a syncopated interlocking of snare and bass hits that is reminiscent of James Brown’s “Funky Drummer.” As if he were following the Bomb Squad’s exact formula, Dr. Dre layered a drum machine (a Roland TR-808) over this break (ex. 3b). The 808 was programmed to add its characteristic bass boom to the first two drum kicks of the “Amen” loop, and to tick off a 16-count hi-hat pulse with a closing hi-hat clasp on the downbeat of every other measure. The “Amen” break and the two hi-hat parts provide the rhythmic foundation around which Dr. Dre places numerous other repeating sounds. Two other ingredients stand out in this beat: a guitar ostinato and a low drone on what sounds like a baritone sax or trombone (or perhaps a downwardly pitched sample of another instrument). The guitar ostinato, which plays straight eighth notes on E-flat except for a one-step descent to D-flat on the “and” of every fourth beat, churns out tight one-measure units of sound (ex. 3c). The horn drone (also on E-flat) has a raw, muddled quality, and casts an ominous cloud over the track.

Unlike the “Amen” breakbeat, the guitar riff and drone sound are not samples taken from other recordings—or at least if they are, they have never been identified. Instead, it is likely that Stan “The Guitar Man” Jones performed the guitar part in studio. Recalling his experiences with N.W.A., Jones explains, “they were using the sample records [but] they couldn’t control the samples. If you wanted to turn the bass up or the guitar up, you couldn’t handle the controls because it was all in samples. That’s when Dr. Dre asked me to replay some of those parts and that’s how I got involved.”31 Although it is unclear what, if any, pre-existing sample Jones imitated for “Straight Outta Compton,” Dr. Dre is known for having studio musicians replay portions of pre-existing records because it allows him greater artistic control over his sources. As Jones implies, by sampling the performances of studio musicians, Dre could manipulate individual lines in his mix (e.g., make the bass louder, or add reverb to the guitar) in ways that he could not accomplish with samples from records. What is more, such an approach to production also made financial sense. Paying musicians a one-time fee for their work in the studio, N.W.A. avoided the expensive master rights (“mechanical royalties”) associated with sampling directly from pre-existing recordings.32

Example 3

(a) Looped portion of the break from the Winstons’ “Amen Brother” (1969).

(b) Roland TR-808 drum sequence from “Straight Outta Compton.”

(c) Looped guitar riff.

Despite Dre’s use of live instrumentation, it is important to note Jones’s acknowledgment that traditional instrumentation in N.W.A.’s recording process was a way of achieving greater control over sample-based production, not a departure from it. Although a live guitarist probably recorded this part, Dr. Dre placed the guitar line in the track as a repeating loop, similarly to how another producer might work with a breakbeat taken from a vinyl record. By combining these layers with the dense percussion track, Dre created a tightly packed funk groove with many sonic similarities to the work of Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad. Like “Rebel Without a Pause,” the track to “Straight Outta Compton” features tight one-measure loops stacked on top of one another to create a thick and intense sound (table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of layers of looped sound in Public Enemy’s “Rebel Without a Pause” and N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton”

Except for the drone, most of the elements in the track have a punchy feel, full of rhythmic stabs and staccato attacks, including the automatic gunfire that Dre samples to follow Ice Cube’s reference to an AK-47 assault rifle. Due to the “noisiness” of the beat, the way sonic space seems filled to maximum capacity, the members of N.W.A.—like Public Enemy’s Chuck D and Flavor Flav—practically yell their verses, as if they must raise their voices to be heard over the cacophony. Even before the actual words to “Straight Outta Compton” are digested, the sound of the track and the group’s vocals evoke the palpable tension of imminent conflict, which reinforces the theme of violent confrontation in the song’s lyrics. For the chorus of “Straight Outta Compton,” Dr. Dre strings together a series of samples with rapid-fire precision. The sound of screeching car tires from Davy DMX’s “One for the Treble” is followed by turntable scratching; the scratching leads directly to a choppy sample of the words “City of Compton” from Ronnie Hudson’s “West Coast Poplock,” followed by more scratching. The whole chain of musical events is deployed over the breakbeat from Funkadelic’s “You’ll Like It Too,” which Dr. Dre splices into the beat just for the chorus.33 The rapid cutting from one sample to the next exemplifies the “rupture” Tricia Rose identifies as fundamental to hip hop’s post-industrial aesthetic.34

The music and lyrics for “Straight Outta Compton” depict the city as a place of extremes, where things happen fast and change is sudden and complete. It is a place where one is either equipped to deal or left behind. In this way, Dr. Dre exploited the spatial characteristics encoded in Public Enemy’s music to depict Compton as place. The sonic characteristics that animated Public Enemy’s militant blackness were rerouted and effectively transposed onto N.W.A.’s depiction of Los Angeles gangstas. In place of Public Enemy’s political theater, however, stood another kind of spectacle that capitalized on the “too black, too strong” sound. As David Toop puts it, N.W.A. had crafted “a nightmarish record, its sound effects of police sirens, gunshots, and screeching tires depicting a generation virtually in the throes of war.”35 Casting their ’hood as a place of chaos and rage, “Straight Outta Compton” scared and titillated audiences with its sensational portrayal of ghetto life.

COMPTON AS CONFRONTATION AND CONTESTATION

Although the lyrics and sound of “Straight Outta Compton” portray the members of N.W.A. as dominant aggressors, the song’s music video, directed by Rupert Wainwright, both amplifies and subverts this impression.36 Ice Cube begins his verse, for example, by referring to himself as a “crazy motherfucker” who will respond violently to anyone who gets in his way. Ren’s verse goes further, challenging the authority of police officers with their “silly clubs” and “fake-ass badges,” and detailing how he would “blast” them with his gun if given the chance. The music video’s opening scenes support this imagery as the group stomps aggressively through the Compton streets. Later, however, N.W.A. is pictured fleeing unsuccessfully from an LAPD squad intent on locking them up. Pursued through back alleys and over chain-link fences, the group members are captured one by one and forced into submission, arms twisted behind their backs, guns pointed at their heads. Taken together, the contrast between these images emphasizes the tightly circumscribed area of Compton and positions N.W.A.’s members as rebels engaged in a turf war with the authorities. In fact, the video opens with a statement critiquing the LAPD’s heavy-handed “gang sweeps.”37

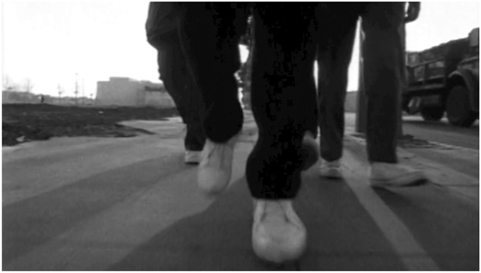

In the music video for “Straight Outta Compton,” the balance of power between the LAPD and N.W.A. is portrayed effectively by a quintessential image of the Southern Californian lifestyle: the automobile. The members of N.W.A. always appear on foot, marching through Compton or fleeing from the police (fig. 16); the police, who presumably do not live in the ’hood, ride in cars that carry them freely in and out of Compton in pursuit of the group (fig. 17). On the one hand, images of the group’s members walking and running through the city’s streets work well to emphasize their connection to place; we are literally getting a “man on the street” perspective. On the other hand, the contrast between these images and those of police cars on the prowl emphasizes the sense of entrapment felt by African Americans living in South Central Los Angeles. Without cars of their own, the group make easy targets for the police, and the video ends with them locked up inside a police van.

Figure 16. Still image of walking feet from the music video for “Straight Outta Compton,” emphasizing N.W.A. members’ proximity to the street.

Figure 17. Still image of rotating tires from the music video for “Straight Outta Compton,” emphasizing the mobility and power of the LAPD.

Figure 18. Still image of the police surveying a map, with a bold outline around the area of Compton, from the music video for “Straight Outta Compton.” (Note the coffee and donut.)

The editing of the video intensifies the theme of conflict, matching the sonic intensity of the song with its rapid pace. The video jumps between images once, twice, even four times per measure. Often, the video juxtaposes the members of N.W.A. and their LAPD adversaries, heightening the tension and sense of imminent conflict. The idea that we are witnessing two rival groups squaring off in a contest over urban space is brought home by a clever use of spatial imagery: the police stand over a map of Compton with its borders inked by a heavy red marker (fig. 18).38

This image of the map, which returns at the song’s chorus, emphasizes the tightly circumscribed area of Compton and the sense of surveillance and limited mobility felt by its inhabitants. Thus, the construction of musical space through sound and imagery portrays the spatial relations of Los Angeles as confining and oppressive to African American residents. The city map, which in another setting might simply function as a means of navigating through the city’s streets, finds itself deployed here as a symbol with sinister implications. Like the ubiquitous “war room” scenes in military-themed movies, the police seem to be strategizing their attack on the people of Compton. In sum, the aesthetics of the music video reflect João Costa Vargas’s observation that South Los Angeles’s ghetto is “the result of widespread social forces galvanized against Black spatial mobility.”39

The aesthetic formula Dr. Dre and N.W.A. created for “Straight Outta Compton” proved a lucrative one. Their follow-up album, Niggaz4Life (1991), which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard charts and reached No. 1 in its second week, featured the single “100 Miles and Running.” The song recycles the imagery and general sensibility of “Straight Outta Compton.” The emcees yell their verses—a “fusillade of threats, obscenities and gunshots”—over a tightly packed, “ferocious” rhythm track.40 The lyrics emphasize the group’s domineering posture, and the music video depicts N.W.A. fleeing from but eventually outsmarting the law.41 Despite the group’s continued success, however, Dr. Dre broke with Eazy-E and manager Jerry Heller soon after the album’s debut, spelling the end of N.W.A. Feeling that his responsibility for generating the music behind the hits warranted a larger share of the profits, Dre sought out a new arrangement with Death Row Records CEO, Suge Knight. In addition to a new, more favorable business arrangement, the beginning of Dr. Dre’s solo career brought about a change in musical aesthetics. Comparing the music and music video of N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton” and “100 Miles and Running” to the hit singles “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” from Dr. Dre’s solo debut The Chronic reveals a profound change in direction, reimagining how the gangsta could navigate Los Angeles’s urban geography.

PRODUCING G-FUNK IN POST-RIOT LOS ANGELES

Released in the final weeks of 1992, The Chronic established Dr. Dre as a viable solo artist. Emphasizing his break with N.W.A., the “Intro” to the album features Snoop Doggy Dogg harshly dismissing Dre’s former associates: “Niggaz Wit Attitudes? Naw, loc. [Loc is a term of casual address, like man or dude.] Niggaz on a mutherfuckin’ mission.” Snoop continues, referring to manager Jerry Heller and rapper Eazy-E derisively as “Mr. Rourke and Tattoo,” references to two characters from the television sitcom Fantasy Island.42 For the music video to one of the album’s three singles, “Wit Dre Day,” Dre ruthlessly parodied, lampooned, and denigrated his two former associates. In the song’s music video, actors playing the roles of “Sleazy-E” and “Jerry” portray Ruthless Records—the partnership between the young African American from Compton and the middle-aged Jew from Cleveland—as exploitative and racist. Jerry refers to Sleazy repeatedly as “boy” and dismissively tells him to “go find some rappers.” The video portrays Eazy-E as a dancing minstrel and wannabe gangsta, mugging for the camera in a vain attempt to make money. The hostile attack vented Dr. Dre’s frustration with Ruthless Records, but more importantly, it provided him with a good vehicle for casting himself and Snoop Doggy Dogg as everything that he claimed Eazy-E was not: authentic. Such accusations, however, would have rung hollow if not for a new artistic vision Dr. Dre introduced after joining Death Row Records. By putting forward an updated version of gangsta cool, The Chronic reached out to new audiences and increased hardcore rap music’s popularity.

Figure 19A. Album cover for N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton (1988).

Figure 19B. Album cover for Dr. Dre’s The Chronic (1992).

This new accessibility is readily visible by comparing the album imagery of The Chronic to that of Straight Outta Compton (fig. 19). On one album cover, Eazy-E stands over the camera with a pistol; on the other, Dr. Dre’s face appears in a design evoking Zig-Zag rolling papers. Potential consumers go from being on the wrong side of a smoking gun to equating the experience of Dr. Dre’s music with the smoking of high-quality marijuana. As Jeff Chang succinctly puts it, “The Black Thing you once couldn’t understand became the ‘G’ Thang you could buy into.”43

Examining The Chronic’s hit singles “Nuthing But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride” in greater detail shows that these differences were also amplified by a change in Dr. Dre’s musical style and video imagery that cast life in the ’hood as less about violent struggle and more about the celebration of a certain kind of freedom and mobility. In fact, analyzing lyrics alone might lead one to miss these changes within the genre. Consider, for example, the lyrics of “Straight Outta Compton” and “Let Me Ride,” both of which stress the gangsterish qualities of their respective protagonists.

N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” begins with a verse from Ice Cube describing himself as a “crazy motherfucker” with a “sawed off” shotgun who will destroy anyone who gets in his way: “squeeze the trigger, and bodies are hauled off.”44 Similarly, Dr. Dre begins “Let Me Ride” by revealing that he’s holding a “Glock” pistol and that the headless bodies of his adversaries are “being found on Greenleaf [street].”45 Taken at face value, both lyrics stress the violence-prone nature of the MCs’ personas and emphasize the perilous nature of life in inner-city Los Angeles. However, there is a subtle difference between the characters portrayed in these songs. In “Straight Outta Compton,” Ice Cube threatens to commit violent acts directly, but in “Let Me Ride” Dr. Dre portrays himself as a gangster of stature. He asserts that he can “make a phone call” to dispose of any unwanted adversaries. In other words, Dre has the ability to have someone killed on demand from afar. In a sense, this shift in perspective reflects the distance traveled by Dr. Dre from his relatively powerless position with N.W.A. to his role as an established hit maker and business partner in Death Row Records. Rather than having to scrap for his daily bread, he now occupies a comfortable seat at the table.

In keeping with this improvement in his circumstances, the music video of “Let Me Ride” portrays Dr. Dre as someone who is able to overcome the geographic challenges posed by Los Angeles, not as someone who remains caught up within its oppressive spatial logic. Rather than running from the police, Dr. Dre spends his time leisurely cruising from liquor store, to barbeque, to car wash, to house party, and so on. “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” repackage gangsta rap as part of a consumable lifestyle that includes marijuana, classic cars, and compliant women. Instead of a turf war with LAPD officers or FBI agents, Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg appear at the scene of mundane, yet stereotypically Los Angeles events. What is more, the locations in which they are pictured are not restricted to Compton or South Central Los Angeles. In fact, many of the park and street scenes featured in the video were shot in the middle-class enclaves of Baldwin Hills and the Crenshaw District, areas that represented upward mobility in black Los Angeles.46 By picturing an experience of Los Angeles rooted in the freedom enabled by the automobile, The Chronic represented Dr. Dre’s upward trajectory and invited viewers to identify with it.

But what did this new gangsta cool sound like?

“NUTHIN’ BUT A ‘G’ THANG” AND “LET ME RIDE”

The short answer is, it sounded freaky. The musical track to The Chronic’s most popular single, “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang,” was based on Leon Haywood’s 1975 hit “I Wanna Do Something Freaky To You.” Released in 1975, Haywood’s song reached No. 7 and No. 15 on the R&B and Pop charts, respectively. The six-minute track, whose orgasmic moaning vocals leave little to the imagination about what this “something freaky” actually is, opens with a relaxed groove featuring drums and wah-wah guitar. The tension begins to build almost immediately as instrumental layers—bass, winds, conga drums, horns, and so on—are introduced one after another. After about a minute of steady accretion, the implied state of arousal increases dramatically with a shift into a new double-time drum pattern.

However, for “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang,” Dre avoided this double-time section completely. Basing his beat on the opening measures of “Freaky” before the song begins reaching toward climax, Dre focused on looping a relatively sparse break that departed significantly from the frenetic energy of the “Funky Drummer” and “Amen”–style breakbeats popular during his tenure with N.W.A. By looping the opening portion of Haywood’s song, Dre locks into place a relaxed groove anchored by a kick-drum pattern that resembles the “and-one, and-three” feel of what many musicians today regard as a basic bossa nova (ex. 4a). Listening closely to the opening of “I Wanna Do Something Freaky To You” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang,” however, reveals something surprising: Dr. Dre doesn’t sample Haywood’s recording, at least not in any straightforward manner. Leading session players in covering Leon Haywood’s original track, Dr. Dre used an Akai MPC 2000 to sample the live studio musicians and create his own interpolation of Haywood’s groove. This decision had an aesthetic purpose: Dre recreates the original Haywood arrangement—only better. The bass is more booming and the snare is more cracking. Indeed, in a genre where timbre is one of the most important musical parameters, hip hop producers are well known for their connoisseurship and obsession with getting just the right sounds for their drums and other instrumental parts. As he did when employing Stan “The Guitar Man” for Straight Outta Compton, Dre departed from a purely sample-based approach. Instead of limiting himself to sounds he could grab from pre-existing records, he sampled live musicians and subjected these recordings to studio manipulation. This practice gave rise to an incredible clarity in the stereo field—very high highs and extremely low lows. Every register of sonic space is filled, without the track sounding muddled.47

Dr. Dre and his session musicians also added something else to Haywood’s groove: more percussion. First, a studio musician used a tambourine to lay down a steady flow of swinging sixteenth notes, which lend the track a compelling and danceable “live” rhythmic feel. Second, they also added the vibraslap, whose rattling announces the downbeat of every fourth measure. The resulting beat for “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang,” with its lilting swing and laid-back drum beat (ex. 4b), sounds less noisy and rigid than the musical track for “Straight Outta Compton,” whose rhythmic foundation consisted of a looped funk break overlaid with a drum machine sequence. This smoother, more open approach gave rise to a beat that allowed Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg to deliver their lyrics in a more relaxed, conversational fashion that contrasts dramatically with the nearly shouting vocals one hears on N.W.A.’s tracks.

Example 4. Comparison of basic bossa nova pattern with the looped drum break and percussion elements in Dr. Dre’s “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang.”

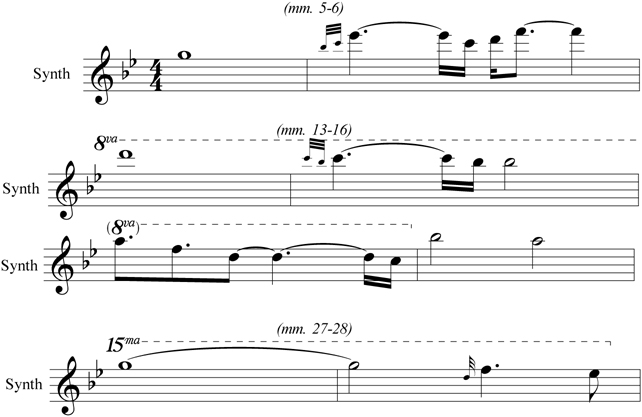

Furthermore, unlike the beat for “Straight Outta Compton,” whose most prominent elements subdivide the groove into tight one-measure units, the keyboard melodies for “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride” imply two- and even four-measure subdivisions of time (ex. 5).48 These melodies, played on one of Dr. Dre’s vintage Minimoog synthesizers, became the characteristic sound of G-funk. The pure whine of the electronically produced sine wave was a timbre well suited to reimagining gangsta rap as more open and accessible than its predecessors. In measure 27 of “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” (ex. 5a), the synthesizer plays the song’s anthemic melodic hook, which Dre interpolated directly from Haywood’s “I Wanna Do Something Freaky To You.” In Haywood’s version, however, this melody is played by string instruments in a lush style similar to disco-soul pioneers Philadelphia International Records. The difference in timbre is striking. The luxurious orchestral timbre of Haywood’s version, replete with the overtones of multiple vibrating strings, contrasts dramatically with the Moog synthesizer’s electronically generated pure sine waves. By making this simple change, Dre maintained the relaxed melodicism of Haywood’s original without evoking any directly audible connection to the disco era. In this way, he was able to open gangsta cool to a laid-back, sensual soundscape without conjuring any images of the polyester tackiness or sexual ambiguity still associated with the fallen genre. As contemporary observers noted, it was this smoother, more pop-oriented sound that opened the door to mainstream radio airplay.49

Example 5. Melodic lines on the synthesizer from “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride.”

(a) “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang”

(b) “Let Me Ride”

Dr. Dre’s adoption of the Minimoog also enabled him to evoke the Afro-futurist sound of Parliament-Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell. George Clinton’s P-Funk collective—from which Dr. Dre adopted “G-funk” to describe his new sound—is central to understanding the way in which The Chronic’s hit singles reimagined gangsta rap, and Worrell’s synthesizer work is prominent on the majority of Parliament’s most popular songs. Throughout the 1970s, he played on and helped arrange numerous hits, including “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” and “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker).” For The Chronic’s two hit singles, “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride,” Dre consciously sought to engage P-Funk’s outer-space sound and imagery. Turning to the music and video for “Let Me Ride” illustrates how Parliament-Funkadelic’s Mothership provided a useful point of reference for Dr. Dre’s rearticulation of race.

THE “MOTHERSHIP CONNECTION” CONNECTION

Describing the Grammy Award–winning single in a 2010 retrospective, music critic Josh Tyrangiel mused, “‘Let Me Ride’ feels like dusk on a wide-open L.A. boulevard, full of possibility and menace.”50 Tyrangiel’s car metaphor is no accident. Like “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang,” the imagery of the video for “Let Me Ride,” and the style in which it is edited, amplify these themes, emphasizing a relaxed and fluid experience of city life. Instead of stuck on the streets battling it out with police, as in the video for “Straight Outta Compton,” Dr. Dre spends the video for “Let Me Ride” cruising around the city in his vintage lowrider, a convertible 1964 Chevrolet Impala. The video opens with Dr. Dre cruising in his car. Close-up shots of the spinning wheels gleaming with chrome emphasize Dr. Dre’s ability to move throughout the city with style (fig. 20). Dre shows off the hydraulic system that makes his car bounce and rise up on three wheels (fig. 21).

These images are juxtaposed with others of Dr. Dre rapping amongst a co-ed crowd of dancing partygoers. The imagery of “Straight Outta Compton,” which cast the urban environment as a site of violent contestation, is replaced by a portrayal of a Los Angeles that offers ample opportunity for pleasure and celebration. For example, the interchange of the I-10 and I-110 freeways (a built feature that helps mark the northwestern boundary of South Central Los Angeles) is pictured in the video for “Let Me Ride” from high above (fig. 22). Rather than evoking the surveillance of police helicopters as one might expect from the gangsta genre, the image of the freeway intersection cross-fades to another shot of Dr. Dre cruising in his car. Such effects emphasize the mobility of the gangsta within the quintessential Los Angeles experience of automobile travel.

Figure 20. Still image of spinning chrome wheels from the music video for Dr. Dre’s “Let Me Ride.”

Figure 21. Still image of Dre’s 1964 Chevrolet Impala rising up on three wheels, from the music video for Dr. Dre’s “Let Me Ride.”

Figure 22. Still image of the I-10/I-110 interchange from the music video for Dr. Dre’s “Let Me Ride.” This image slowly fades into another shot of Dre cruising in his car.

N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” used no such fade-ins or fade-outs to transition between images. Rather, the video’s editors employed sharp jump cuts, which emphasize the conflict between the police and members of the group. In the video for “Let Me Ride,” fade-ins and fade-outs present smooth transitions between images. These effects imply that Dr. Dre moves fluidly between activities, riding in his car, rapping in the streets, shopping at the liquor store, and so on. The pace of the editing also matches the more relaxed feel of the musical track. Cutting between images occurs at a pace of about once per measure, and in some places even less frequently. The video’s emphasis on mobility is amplified by the song’s chorus, which features lengthy samples drawn from Parliament’s “Mothership Connection (Star Child).” One of these samples comes from live footage of a P-Funk concert, where the song was used at the climax of the performance to signal the arrival of the Mothership.51

At the height of their popularity (1976–77), George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic collective toured the United States with an elaborate costumed stage show animating the group’s funky mythology, including a giant spaceship that descended from above carrying Dr. Funkenstein (played by group leader George Clinton, of course).52 P-Funk lore posited an Afrocentric universe with black people at the center of history. As Rickey Vincent explains, “Clinton and crew developed their own creation myths and their own black science-fiction in which the values and attributes alluded to by The Funk constituted the resolution of each tale.”53 At the point in the concert preceding the Mothership’s arrival, the performers encouraged the audience to join in singing the refrain, “Swing down sweet chariot, stop, and let me ride.” After intoning these words for several minutes, the band produced the Mothership, which descended from the rafters with Clinton aboard. The preeminent symbol of Clinton’s “Afro-futurist” imagination, the Mothership symbolized the African American drive for freedom through a playful evocation of space travel.54

Rather than use samples to break up time into a quick succession of discrete musical events (as in the chorus of “Straight Outta Compton”), the chorus of “Let Me Ride” features a lengthy loop of “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” that repeats four times without interruption. Taking the sound and imagery of the music video together, we can easily imagine this chorus as music being played through the sound system in Dre’s 1964 Impala. We even hear Dr. Dre’s voice respond enthusiastically to each repetition of “swing down sweet chariot, stop and let me ride” with the phrase “Hell yeah,” creating an uncanny call-and-response between the sample and Dre’s “live” performance: his words, which could be directed at listeners—but more likely at the Parliament hook itself—imply a performance within a performance and grant a sudden authority to the sampled material. It is as if in this instance, Dr. Dre relinquishes the spotlight as the rap star and calls our attention to the power of “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” and its promise of transcendence.

Dr. Dre’s particular use of “Mothership Connection” can be best characterized as “reverse troping,” a practice that musicologist Felicia Miyakawa describes as “[using] snippets of borrowed material to comment on new texts and music.”55 Although hip hop producers often manipulate samples with little regard for their original contexts or meanings—what we might consider a purely formalist approach to sound collage—Miyakawa’s work reminds us that beat makers also choose samples that comment on lyrics and amplify other elements within a musical track. The chorus of “Let Me Ride” (“swing down sweet chariot, stop and let me ride”) is a clear example of such practices. Dr. Dre’s sampling does not reflect a “pure” aestheticism unconcerned with the original meaning of the P-Funk sample; it reflects, instead, a deliberate attempt to make a thematic and symbolic connection to the sampled source. This view is confirmed by the music video for “Let Me Ride,” which ends with the splicing in of footage from a live P-Funk concert. As George Clinton (playing the role of Dr. Funkenstein) disappears into the Mothership behind a white veil of artificial fog, Dr. Dre’s face is superimposed over the concert footage where Clinton was standing. This creative decision might seem overly grandiose and presumptuous, but it also suggests we take seriously the connection between the imagery and aesthetics of “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” and “Let Me Ride.”

G-funk’s new drive to spatial transcendence comes into clearer focus if we examine “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” from the perspective of cultural insiders. The “sweet chariot” that forms the subject of the chorus to “Let Me Ride” touches on a trope with roots deep in the African American past.56 In fact, references to celestial chariots of various types had already become standard practice in earlier African American musical genres, and the celestial chariots of the bible had already been recast as real-world vehicles in numerous blues, gospel, and funk songs.57 As Robin Kelley traces the badass pose and bawdy lyrics of gangsta rap back to African American folk tales of Stagger Lee and various off-color blues numbers, we can also identify an equally rich pedigree underlying Dr. Dre’s decision to cast his 1964 Chevrolet Impala as a vehicle with transcendental powers.

In many ways, George Clinton’s wacky P-Funk mythology reads like a parody of the Nation of Islam’s cosmogony as explained by the honorable Elijah Mohammed. The Nation of Islam’s foundational myth recasts U.S. race relations as the result of an ancient experiment by an evil “big-head scientist,” Yakub, who created the white race through genetic experimentation. The white race went on to enslave and oppress the black man through lies and trickery, and the Nation of Islam strives to bring about the end of the white race’s rule, freeing the black man.58 Freedom is imagined to be possible through the divine intervention of the Mother Plane. With Elijah Mohammed seated as a rider in this divine chariot, the Mother Plane enacts “apocalyptic retribution” against the sins of the white race, destroying the world created by the white race and restoring order to the universe.59

In an exploration of the biblical roots of the Nation of Islam’s cosmogony, Michael Lieb interprets Mohammed’s vision of the Mother Plane as a revision of the biblical story of Ezekiel’s wheel: a vision of God’s power symbolized by turning, levitating, burning wheels.60 Lieb argues that Ezekiel’s wheel informs numerous aspects of U.S. culture, particularly those points at which the uses and abuses of technology become suffused with divine character. In other words, the story of Ezekiel’s wheel has become a trope for the human race’s attempts to harness the power of God through technological means. Often the appropriation of divine technology leads to the compulsion to use heavenly powers to triumph over all those who stand in one’s way. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the apocalyptic scenario Elijah Mohammed envisioned was especially attractive to an African American community deeply oppressed by a white majority.

As Lieb points out, however, Mohammed’s narrative was not without precedent in African American culture. The brilliance of his vision lies in the way he titrated a new reading of Ezekiel’s wheel with themes already circulating within black culture. For example, there are a numerous spirituals that make reference to the divine chariots of the Bible. The most famous, of course, is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which is actually about Elijah’s chariot (Kings 2:11). In other songs, the chariot was equated with a train, a form of mechanized technology that became a symbol of mobility and freedom for black southerners during the Great Migration. In fact, George Clinton may have borrowed the hook for the chorus of “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” from one such spiritual: “Train coming, oh let me ride/. . . Oh low down the chariot and let me ride.”61 Reimagining the death-dealing Mother Plane as an intergalactic party machine, P-Funk mythology offered listeners a vision of dance-floor transcendence with racialized religious overtones. Dr. Dre’s 1964 Impala represents the next link in this signifying chain.

Robert Farris Thompson has written about the long tradition of automobiles, trains, and wheels representing transcendence in African American culture. Thompson recounts poet Daniel G. Hoffman’s characterization of the train whistle as the distinctive symbol of black yearning, invoking themes of space, distance, and movement.62 In more recent times, Thompson argues that the “locomotive wail” has given way to an appreciation of the “beauty of travel and transcendence” in “revolving, shining hubcaps” and the “turning of a rubber tire.”63 In Thompson’s words, “automotive flash” has superseded the train whistle as the preeminent symbol of “black quest.”64 The sense of freedom and mobility portrayed in The Chronic’s two singles “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” draw from this symbolic history.

Yet, it has been difficult for some critics to accept G-funk’s “Afro-futurist” elements. In an article responding to the rise of outer-space themes in Lil Wayne’s music, Jonah Weiner contends that until Lil Wayne began describing himself in extraterrestrial terms, gangsta rap had turned its back on Afro-futurism, planting itself firmly in the earthbound contexts of the ’hood. Under Dr. Dre’s influence, according to Weiner, “cosmic journeys became fanciful departures from hip-hop’s so-called ‘true’ locus, the flesh-and-blood, asphalt-and-concrete street.”65 Although there is some truth to Weiner’s assertion about gangsta authenticity being firmly planted in the ’hood, we have also seen the extent to which Dr. Dre relied on the music of George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic, the Afro-futurist group par excellence. In the case of G-funk, the Afro-futurist impulse was not jettisoned; it was selectively tapped for a new purpose. Dr. Dre’s 1964 Impala represents the sweet chariot–cum–Mother Ship rearticulated for the new millennium. The irony of Dr. Dre’s songs “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” is that they used the cultural resources of 1970s Afro-futurism to help promote what many regard as a negative, materialistic turn in rap music.66 Dr. Dre appropriated the Mothership as a symbol of mobility, translating Clinton’s funky ideology of freedom and collective salvation into a means of individual transcendence. The collective will and striving of a people symbolized by Mohammed’s sweeping religious narrative (and Clinton’s funky parody) finds itself recast as an earthbound vehicle seemingly directed at nothing more than the assertion of individual, which is to say gangsta, agency.

THE SOUND OF POST-SOUL SPACE

Reflecting on conceptions of freedom as they are expressed through African American cultural forms, Paul Gilroy has criticized the emergence of “automotivity” as a central trope of late-twentieth- and early-twenty-first-century black striving. Although Gilroy remains sensitive to the history of “racial terror, brutal confinement, and coerced labour” that makes the car so attractive as a symbol of black escape, he ultimately concludes that the investment in expensive, shiny automobiles—like other forms of conspicuous consumption—offers only a simulation of liberation.67 In fact, given the individualistic nature of cars as commodities, he asserts that the automobile has become “the instrument of segregation and privatization, not an aid to their overcoming.”68 Gilroy’s concerns are motivated, not surprisingly, by his appraisal of the state of hip hop culture and rap music at the dawn of the new millennium. Titling the chapter from which the previous quotes were drawn “Get Free or Die Tryin’,” he makes a play on rapper 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ (2003), the multi-platinum-selling debut album produced by none other than Dr. Dre.69 Taking aim at “bling” style, Gilroy decries the celebration of material gain and consumptive practices that have replaced previous (read as civil rights–era) metaphors for human freedom and equality in black popular culture.

Making this departure from more collective, community-centered ideas about freedom and success central to her analysis of gangsta rap, Eithne Quinn casts the sound, imagery, and lyrics of G-funk as the musical equivalent of what Nelson George terms a “post-soul” sensibility. According to George, the post-soul sensibility encompasses the “death of politics,” materialism, individualism, and an anti-romantic attitude toward sex.70 Quinn finds this ideology crystallized in G-funk’s main themes: cruising, marijuana, money making, and casual sex.71 Yet, she avoids pinning the blame for these attitudes on gangsta rappers themselves and insists that we examine them against the political backdrop of neoliberal economic and social policy. Turning our attention to the articulation of G-funk’s sound and imagery and their reception suggests that Dr. Dre’s “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride” sounded race as black neoliberalism.

David Harvey explains that “neoliberalism is in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.”72 Gaining traction in the late 1970s and 1980s, neoliberal policies, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), sought to dismantle barriers to free trade and investment. They also took aim at state programs, such as welfare and other social services, deemed to be impeding entrepreneurial freedom and economic activity. In the United States, such policies tend to favor private capital over public institutions, and the 1980s and 1990s witnessed the steady erosion of programs set up in the mid-twentieth century to ensure public well-being. Welfare reform, the defunding and privatization of public services, and the deregulation of industry are all facets of neoliberal policy. As critics of neoliberalism (including Harvey) argue, the human costs of applying market-based logic to economically vulnerable communities have been severe. Welfare reform might in principle seek to decrease dependency and “liberate” the workforce, but by stripping citizens of institutional protections, neoliberal economic policy leaves few choices to the economically disadvantaged, whether they are living in 1980s Compton or present-day Bangladesh.

Yet, one of neoliberal ideology’s main strengths has been the ease with which it is absorbed by the culture at large, affecting how people view themselves as workers and consumers. As Harvey notes, neoliberalism has worked its way into our habits of thought to become “the common-sense way many of us interpret, live in, and understand the world.”73 By attaching itself to political ideals of “human dignity” and “personal freedom,” neoliberalism has been embraced even by those whose well-being has suffered the most under its policies. Thus, rather than understand gangsta rap’s individualistic ethos as a pathology of underclass black youth—as many critics of the music have done—it is better to interpret the post-soul sensibility in G-funk as a political strategy of economic survivalism. As Quinn explains, “Gangsta’s governing ethic of aggressive economic self-determination is clearly legible when seen as a tactical response to the steady depletion of resources, rights, and modes of resistance.”74 In other words, the economic and social policies of the Reagan-Bush years created an environment that necessitated and rewarded the adoption of a survival-of-the-fittest mentality.75 Analyzing Dr. Dre’s and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s lyrics as primary evidence, Quinn claims that “much of the social significance [of G-funk] derived from its ability to articulate post–civil rights ideas about family, work, masculinity, and advancement.”76

Examining another set of lyrics from “Let Me Ride,” we can clearly see how G-funk rejected previous forms of black politics centered on collective action. Promising “no medallions, dreadlocks, or black fists,” Dre names and rejects three symbols of black collectivity and resistance: the African medallions made popular by neonationalist group Public Enemy, dreadlocks symbolizing Rastafarianism, and black fists associated with the Black Power movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. These symbols of black freedom find themselves supplanted by the gangsta, whose ruthless entrepreneurial activity through rap leads to financial success (“that gangsta shit that makes me gangs of snaps”), coded here as the true form of liberation. What role do Dr. Dre’s musical choices play in advancing this neoliberal attitude toward culture and politics?

Quinn briefly characterizes the musical aesthetics of G-funk as “laid-back,” “low metabolism” beats mirroring the nonchalant attitude of G-funk artists.77 There is some truth to this description: it is difficult to imagine Snoop Doggy Dogg seated on a porch—as he is in the video for “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?”—delivering his smooth Calabama drawl over the frenetic beat from “Straight Outta Compton.” But I am skeptical about her assertion that Dr. Dre’s sampling of Parliament-Funkadelic, as well as other soul artists of the 1960s and 1970s, was an act of nostalgia signaling the genre’s deepening engagement with its parent culture.78 The problem with this explanation is that Dr. Dre—like virtually all hip hop producers active in the late 1980s and early 1990s—had been sampling the soul music of the 1960s and 1970s throughout his tenure with N.W.A. What had changed by 1993 was not necessarily the artists he chose to sample, but rather the kinds of breaks that he chose and the way that he manipulated them to curate an overall vibe that differed from his previous work.

Rather than simply hearing the music as a nostalgic yearning for community that counter-balances harsh lyrics and imagery, it is also plausible to hear Dr. Dre’s rearticulation of P-Funk’s transcendental hippie vibe as complementary to the ruthless individualism of post-soul politics. The relaxed groove of “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and the spacious soundscape of “Let Me Ride” helped portray the gangsta as a sophisticated entrepreneur able to rise above his surroundings to conquer the dog-eat-dog world of the ghetto. What our close look at the sound and imagery of these songs reveals is the extent to which the aesthetics of G-funk draw, refashion, and rearticulate soul music’s collectivist project for the neoliberal era. The music is not simply a nostalgic or ironic background against which we witness the same old portrayals of gangsta identity. Instead, the music is an active player, just as important as the lyrics, publicity imagery, reception discourse, and political context that Quinn so astutely analyzes. Indeed, it is the musical “mapping” of urban space in “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” that helps reflect gangsta rap’s acceptance of neoliberal hegemony.

CONCLUSION: BIRTH OF THE BLING

The sound of The Chronic’s hit singles differed remarkably from that of N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton or Niggaz4Life, shifting from a frenetic and noisy aesthetic to one that sounds significantly more open and relaxed. In contrast to N.W.A.’s music videos, which featured the group’s members under police surveillance and being chased through South Central L.A.’s streets, the videos for The Chronic’s “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride” evoked a new sense of mobility and freedom for the gangsta. Rather than presenting the ’hood as a place of conflict and struggle, the gangsta experience was offered up as a site of pleasure one might comfortably attempt to re-create within the confines of one’s own car or suburban home. Drawing on a variety of cultural resources, Dr. Dre crafted an aesthetic that detached the image of the gangsta from its embattled origins in the ghetto and made him a symbol of unfettered mobility thanks to entrepreneurial striving. The Chronic’s commercial success thus foreshadowed a change taking place in the music and advertising industries: the gangsta would soon leave the world of malt liquor and blue-collar fashion behind, becoming by the end of the twentieth century one of the dominant models of conspicuous consumption.

A glance at more recent popular culture shows just how far gangsta has come. By the end of the 1990s, rap music symbolized a level of economic success and lavish consumption unimaginable at the time of the genre’s birth. In a 2008 comedy sketch on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, Stewart, who is white, and African American cast member Wyatt Cenac played a fake game show entitled “Rapper or Republican?” The skit’s punch lines involved Stewart’s being unable to tell the difference between various rap artists and famous conservatives. After hearing clues about their various business dealings, Stewart ends up confusing Ice-T and Fred Thompson, DJ Quik and Larry Craig, and 50 Cent and Mitt Romney.79 In the 1980s, a satirist might have skewered Donald Trump or Leona Helmsley as signs of ultraconservatism and materialistic excess; in the 2000s, rap musicians made equally inviting targets. Gangsta rap has thus become a metaphor for the ruthless profit-seeking and seductive pleasures of capitalism.80

These shifts in political and aesthetic orientation help explain the conflicting assessments of The Chronic by fans, critics, and historians. Even Robin D. G. Kelley, whose analysis of gangsta rap remains one of the most sympathetic and thoughtful explorations of the genre’s significance, seemed disturbed by the “senseless, banal nihilism” and misogyny he hears in Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s music.81 Assessing the state of gangsta rap at the end of 1993, Kelley feared that rap music was not taking the progressive turn many had hoped for. Far from it—the music seemed reduced to, as he put it, “nihilism for nihilism’s sake.”82 Writing for the Village Voice, Robert Christgau also refused to buy into the hype, dismissing The Chronic’s “conscienceless” violence and smooth style of production as “sociopathic easy-listening.”83 However, for many others the arrival of Dr. Dre’s solo album took hip hop to new heights. The Source magazine praised The Chronic as an “innovative and progressive hip hop package,” awarding the album four and a half microphones (out of five).84 Seemingly unconcerned with the album’s casual violence and misogyny, the review heaped praise on Dr. Dre’s music production.

Rather than understand these appraisals of The Chronic’s worth simply as contradicting opinions, I want to suggest that they represent two sides of the same coin. The political and aesthetic dimensions of the album are both critical to the way that Dr. Dre presents his vision of the good life. If Straight Outta Compton was designed to force listeners to confront the harsh, hidden realities of inner city life, The Chronic’s two hit singles seemed intent on meeting suburban listeners closer to home. As a final example, consider Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s appearance with host Fab Five Freddy in a 1993 episode of Yo! MTV Raps. The episode was set, not in the inner city neighborhood of Compton, but in the back yard of Dr. Dre’s expansive suburban Woodland Hills home.85 Conducting the interview with Fab Five Freddy at a poolside barbeque replete with nameless, bikini-clad “honies,” the duo presented a vision of the gangsta lifestyle filled with endless sunshine, objectified women, and hedonistic consumption. Discussing his obsessive studio work ethic, The Chronic’s multi-platinum sales, and Snoop’s forthcoming solo debut Doggystyle, Dr. Dre also jokes with the young ladies, exhorting them to “keep hope alive” and asking them “Why can’t we all get along?” Signifying on the iconic words of Jesse Jackson and Rodney King, respectively, these utterances perform a dual function: flirting with the “honies” while also trolling the naive optimism of civil rights–era politics. The easy way that Dr. Dre and Snoop Doggy Dogg conduct themselves in front of the camera—much like their G-funk musical style—suggests a cool and cynical accommodation with the realities of the neoliberal era.86 Sociopathic easy-listening indeed.

The Chronic’s sounding of race as gangsta cool encapsulates our culture’s ambivalence regarding the promises and pitfalls of capitalism. In introducing a new sense of rap authenticity, Dr. Dre set the tone for the genre’s commercial expansion in the 1990s as a fantasy world of champagne, SUVs, and private jets. Adam Krims argues that rap music’s turn toward “bling” and conspicuous consumption in the mid-1990s reflected and participated in the middle- and upper-class “reconquest of the American metropolis,” more commonly known as “gentrification.”87 If N.W.A.’s music predicted the riots, mapping the hostile terrain where African American youth confronted the LAPD, then perhaps Dr. Dre’s The Chronic foreshadowed the gradual gentrification of urban space in post-riot Los Angeles. This new style of consumption was accompanied and abetted by a new musical mapping of Los Angeles. Thus, The Chronic and Dr. Dre’s drive into the popular mainstream was tied to a spatial project that far exceeded the boundaries of the recording industry.