Face

Analysis: the checklists

Midface injury

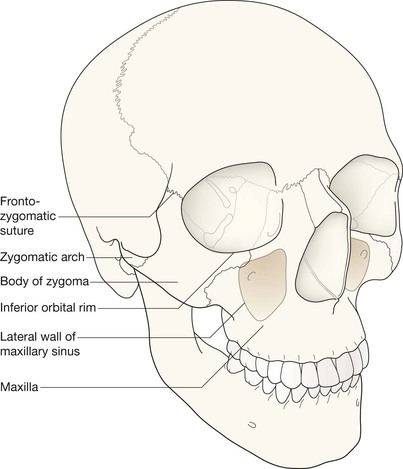

The midface anatomy appears very complex. Try this approach. Think of the zygoma (malar bone) as a midface stool with four legs. The seat of the stool is very strong. The four legs are much weaker, so you need to assess each leg very carefully.

A five-point checklist

Inspect the OM views as follows:

Concentrate on the stool's legs. For each leg compare the injured side with the other (normal) side. Look for any asymmetry or any difference between the appearance of the matching legs. Check as follows:

2. Leg 2: frontal process of the zygoma.

4. Leg 4: lateral wall of the maxillary antrum.

5. Look for fractures and look for:

□ a fluid level (blood from a fracture) in the maxillary antrum;

Always apply this rule: If any one of the legs is fractured then always, always, double check whether the other three legs of the midface stool are intact (see Tripod fracture, p. 63).

Suspected blow-out fracture

Evaluate the OM view (see p. 66).

Injury to mandible

Evaluate the OPG view (see pp. 68–70).

The common injuries

Injuries to the midface

Arguably it would be more accurate to call it a quadripod fracture4,13.

The Tripod fracture is also known as: Zygomaticomaxillary fracture complex; Zygomaticofacial fracture; and Trimalar fracture3.

Tripod or quadripod? Terminological discord

The term “tripod fracture” is accepted common usage, derived from an analogy to a three legged stool to describe the midface anatomy3,4,14. We agree with Daffner4 that there are really four legs supporting the stool (the zygoma), so we evaluate the four legs (pp. 58–59). Some other authors envisage a three legged stool as follows:

▪ The malar eminence of the zygomatic bone (the cheek bone) is regarded as the seat of a stool3,4,14.

▪ The three legs are: (1) the zygomatic arch running backwards; (2) the fronto-zygomatic process running upwards; (3) the maxillary process running anteriorly and medially. This third leg is visualised as a somewhat splayed and hollowed out structure4 forming the floor of the orbit as well as the lateral wall of the maxillary antrum.

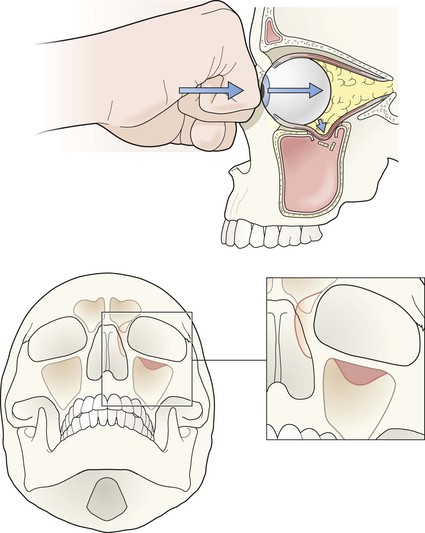

Orbital blow-out fracture

Following blunt trauma, this injury may be isolated, or accompany any other major or minor facial injury13. It results from a direct compressive force to the globe (ie the eyeball), commonly from a fist, elbow, dashboard, car seat, or small object such as a squash ball.

The diameter of the object that compresses the eyeball is invariably greater than the diameter of the eyeball itself. The blow causes a sudden increase in the intraorbital pressure behind the eyeball, resulting in a fracture or fractures of the thin and delicate plates of bone that form the floor and the medial wall of the orbit.

Approximately 20–40% of patients with an orbital floor blow-out fracture also have a fracture of the medial wall of the orbit15.

Clinical impact guidelines

▪ Imaging for a suspected orbital blow-out fracture: only patients with a clear clinical indication for surgery require imaging16. Ultrasound evaluation is generally preferable to radiography.

▪ If some of the orbital contents herniate downwards through the orbital floor then the inferior rectus muscle may become tethered. Tethering will result in diplopia/opthalmoplegia.

▪ Decisions regarding the need for surgery revolve around:

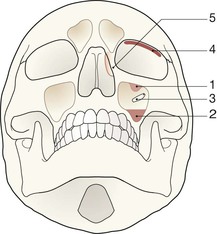

Orbital blow-out fracture—the OM findings

▪ The strong inferior orbital margin remains intact when a blow-out fractureis an isolated injury.

▪ Some orbital contents (fat and/or the inferior rectus muscle) may herniate downwards through the delicate orbital floor. This appearance has been likened to an opaque teardrop hanging from the roof of the maxillary antrum1. This teardrop may be the only radiographic evidence of a blow-out fracture.

▪ The bone fragment (from the orbital floor) is very thin and is rarely seen.

▪ Sometimes a blow-out fracture may be inferred because air from the breached sinus has entered the orbit. This orbital emphysema may be positioned above the eyeball. Air appears black on the radiograph. This has given rise to the description of the “black eyebrow” sign.

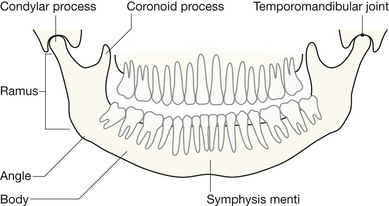

Injuries to the mandible

Assessing the OPG

Sometimes the panoramic view (OPG) fails to show a fracture17. It is very important that radiological evaluation of the mandible is correlated with the precise site of clinical concern. The symphysis is particularly difficult to evaluate on an OPG; a near normal appearance may occur when fragments override each other. Clinical suspicion must always take precedence over a seemingly normal OPG. If there is any doubt, then additional radiography is indicated—a PA radiograph in the first instance.

Important points to check

▪ Think of the mandible as a rigid ring of bone. When a ring of bone is broken it is very common for two fractures to occur in the ring. 50% of mandible fractures are bilateral18.

▪ Always check for symmetry—compare one side of the mandible with the other.

▪ Check for fractures of the body and angle of the mandible.

▪ Assess the mandibular condyles carefully. Fractures here may be very subtle.

▪ Check for correct dental occlusion. The upper and lower teeth should have even and equal spacing on the radiograph. Displaced fractures, or a fracture through the neck of a condyle, frequently produce uneven spacing between the teeth4,11.

▪ Check for any step deformity in the line of the teeth of the lower jaw. This invariably indicates a fracture.

▪ Assess the temporomandibular joint (TMJ, see p. 56).

Be careful. The OPG will produce some appearances that can be confused with a fracture. These artefacts are mainly due to the overlapping image of the pharynx or tongue. Familiarity with the possible artefacts (pp. 69 and 72) will prevent an incorrect interpretation.